Sir William Johnson, 1st Baronet (c. 1715 – 11 July 1774), was a British Army officer and colonial administrator from Ireland known for his military and governance work in British colonial America.

Sir William Johnson | |

|---|---|

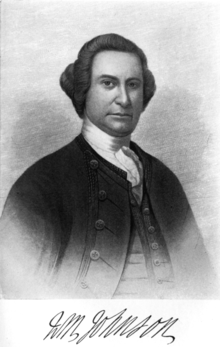

Sir William Johnson in 1763, based on a lost portrait by Thomas McIlworth[1] | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1715 County Meath, Ireland |

| Died | 11 July 1774 (aged 58–59) Johnstown, New York |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1744–1774 |

| Rank | Major-General Superintendent of Indian Affairs |

| Commands | Expedition to Crown Point Expedition to Fort Niagara |

| Battles/wars | |

As a young man, Johnson moved to the Province of New York to manage an estate purchased by his uncle, Royal Navy officer Peter Warren, which was located in territory of the Mohawk, one of the Six Nations of the Iroquois League, or Haudenosaunee.

Johnson learned the Mohawk language and Iroquois customs, and was appointed the British agent to the Iroquois. Johnson commanded Iroquois and colonial militia forces against the French and their allies during the French and Indian War (1754–1763). His role in the British victory at the Battle of Lake George in 1755 earned him a baronetcy of New York. His capture of Fort Niagara from the French in 1759 brought him additional renown.

Throughout his career as a British official among the Iroquois, Johnson combined personal business with official diplomacy, acquiring tens of thousands of acres of Native land and becoming very wealthy.

Early life and career

editWilliam Johnson was born around 1715 in County Meath, in the Kingdom of Ireland.[2] He was the eldest son of Christopher Johnson (1687–1764) of Smithstown, County Meath and Anne Warren, daughter of Michael Warren of Warrenstown, County Meath and Catherine Aylmer, sister of Admiral Matthew Aylmer, 1st Baron Aylmer.

His mother Anne was from an "Old English" Catholic gentry family who had, in previous generations, lost much of their status to Protestant English colonists.[3] His father was descended from the O'Neill of the Fews dynasty of County Armagh. William Johnson's paternal grandfather was originally known as William MacShane, but changed his surname to Johnson, the Anglicization of the Gaelic Mac Seáin.[4]

Some early biographers portrayed William Johnson as living in poverty in Ireland, but modern studies reveal that his family lived a comfortable, if modest, lifestyle.[5] Although the Johnson family had a history of Jacobitism, William Johnson's maternal uncle Peter Warren was raised as a Protestant to enable him to pursue a career in the British Royal Navy. He achieved considerable success, gaining wealth along the way.[6]

As a Catholic, William Johnson had limited opportunities for advancement in the institutions of the British Empire.[7] Never particularly religious, Johnson converted to Protestantism when offered an opportunity to work for his uncle in British America.[8]

Immigration to the colonies

editPeter Warren had purchased a large tract of undeveloped land along the south side of the Mohawk River in the province of New York then known as Warrensberg (or Warrensbush) present day Florida, NY. Warren convinced Johnson to lead an effort to establish a settlement there, to be known as Warrensburgh, with the implied understanding that Johnson would inherit much of the land.[9] Johnson arrived in about 1738 with twelve Irish Protestant families and began to clear the land.[10] He purchased enslaved Africans to do the heavy labor of clearance; they were the first of many slaves bought by Johnson.[11]

Warren intended Johnson to become involved in trading with American Indians, largely the Mohawk and other of the Six Nations of the Iroquois, tribes who dominated the area west of Albany. Johnson soon discovered that the trade routes were to the north, on the opposite side of the river from Warrensburgh.[12] Acting on his own initiative, in 1739 Johnson bought a house and small farm on the north side of the river, where he built a store and a sawmill. From this location, which he called "Mount Johnson", Johnson was able to cut into Albany's Indian trade. He supplied goods to traders who were headed to Fort Oswego, and bought furs from them when they returned downriver. He dealt directly with New York City merchants, thus avoiding the middlemen at Albany.[13] The Albany merchants were irate, and Warren was not pleased that his nephew was becoming independent.[14]

Johnson became closely associated with the Mohawk, the easternmost nation of the Six Nations of the Iroquois League. By the time Johnson arrived, their population had collapsed to 580 persons, due to chronic infectious diseases unwittingly introduced by Europeans and warfare with competing tribes related to the lucrative beaver trade.[15] The Mohawk thought an alliance with Johnson could advance their interests in the British imperial system. Around 1742, they adopted him as an honorary sachem, or civil chief, and gave him the name Warraghiyagey, which he translated as "A Man who undertakes great Things".[16]

King George's War

editIn 1744, the War of the Austrian Succession spread to colonial America, where it was known as King George's War. Because of his close relationship with the Mohawk, in 1746 Johnson was appointed by the British colonial government as New York's agent to the Iroquois, replacing the Albany-based Indian commissioners.[17]

The newly created "Colonel of the Warriors of the Six Nations" was instructed to enlist and equip colonists and Indians for a campaign against the French.[18] Recruiting Iroquois warriors was difficult: ever since the so-called Grand Settlement of 1701, the Iroquois nations had maintained a policy of neutrality in colonial wars between France and Great Britain.[19] Working with the Mohawk chief Hendrick Theyanoguin, Johnson recruited Mohawk warriors to fight on the side of the British.[20] Johnson organized small raiding parties, which were sent against the settlements of the French and their Indian allies.[21] In accordance with New York's Scalp Act of 1747, Johnson paid bounties for scalps, although he realized this encouraged the scalping of non-combatants of all ages and both sexes.[22] In June 1748, Johnson was appointed as "Colonel of the New York levies", a position that gave him additional responsibility for the colonial militias at Albany.[23] In July 1748, word was received of a peace settlement. The Mohawk had suffered heavy casualties in the war, which lessened Johnson's prestige among them for a while.[24]

In 1748, Johnson built a new stone house upriver from Mount Johnson, which became known as Fort Johnson.[25] The home was strongly fortified when the next war approached.

New York Government

editAfter King George's War, Johnson was caught between rival New York political factions. One faction was led by Governor George Clinton, who had appointed Johnson as New York's Indian agent and, in 1750, appointed him to the Governor's Council.[26] Governor Clinton urged the New York Assembly to repay Johnson's outstanding wartime expenses, which amounted to £2,000.[27] Repayment was blocked by Clinton's political rivals, a faction led by Lieutenant Governor James De Lancey, who was connected to the Albany Indian commissioners whom Johnson had supplanted. De Lancey was also the brother-in-law of Admiral Peter Warren, which added to the strain in the relationship between Johnson and Warren.

An exasperated Johnson resigned as New York's Indian commissioner in 1751.[28] When Warren died in July 1752, he left nothing to Johnson in his will. Although Warren died a very wealthy man, in his will he required that Johnson repay the expenses incurred while settling Warren's land.[29]

In 1755, Johnson shifted the primary meeting place for diplomatic councils between the British and the Iroquois from Albany to Fort Johnson.[30] He also bought houses in Schenectady and Albany to stop at on his business trips to New York Town.[31]

French and Indian War

editIn June 1753, Hendrick Theyanoguin and a delegation of Mohawk traveled to New York City, where they announced to Governor Clinton that the Covenant Chain—the diplomatic relationship between the British and the Iroquois—was broken.[32] The British government ordered Clinton to convene the Albany Congress of 1754 to repair the Covenant Chain.[33] At the Congress, the Mohawk insisted that the alliance would be restored only if Johnson were reinstated as their agent.[34]

Johnson's reinstatement as Indian agent came the following year, just as the French and Indian War, the North American theater of the Seven Years' War, was escalating. In 1755, Major General Edward Braddock, sent to North America to direct the British war effort, appointed Johnson as his agent to the Iroquois.[35] Although Johnson had little military experience, he was commissioned as a major general and instructed to lead an expedition against the French fort at Crown Point.[36] His troops were provincial soldiers paid for by the colonies, and not regular soldiers of the British Army, which meant that he had to deal with six different colonial governments while organizing the expedition.[37]

Johnson initially had nearly 5,000 colonials at his command, but General William Shirley, the governor of Massachusetts commissioned to lead a simultaneous expedition to Fort Niagara, shifted some of Johnson's men and resources to his own campaign against the French post.[38] Tensions escalated as the two generals worked against each other in recruiting Native allies. The dispute was complicated by the unusual command structure: as Braddock's second-in-command, General Shirley was Johnson's superior officer, but when it came to Indian affairs, Johnson was theoretically in charge.[39] In time, Shirley would blame the failure of his expedition on Johnson's refusal to provide him with adequate Indian support. According to the Johnson biographer Milton Hamilton, historians usually portrayed Johnson as acting unreasonably in the controversy with Shirley, but Hamilton argued that Johnson was reacting to Shirley's clumsy Indian diplomacy, which harmed the British relationship with the Six Nations.[40]

Crown Point expedition

editMarching north into French territory, in August 1755 Johnson renamed Lac du Saint-Sacrement to Lake George in honour of his king.[41] On 8 September 1755, Johnson's forces held their ground in the Battle of Lake George. Johnson was wounded by a ball that was to remain in his hip or thigh for the rest of his life.[42] Hendrick Theyanoguin, Johnson's Mohawk ally, was killed in the battle, and Baron Dieskau, the French commander, was captured. Johnson prevented the Mohawk from killing the wounded Dieskau, an act memorialized in later paintings of the event.[43]

The battle ended the expedition against Crown Point. Johnson built Fort William Henry at Lake George to strengthen British defences.[44] In December, tired of army life, Johnson resigned his commission as a major general.[45] General Shirley, who had become the commander-in-chief upon Braddock's death, sought to have Johnson's commission as Indian agent modified so that Johnson would be placed under his command.[46] But Shirley was soon replaced both as governor and commander-in-chief, while Johnson's star was on the rise.[47]

Although the Battle of Lake George was hardly a decisive victory, the British needed a military hero in a year of major setbacks, and Johnson became that man.[48] Claims that Johnson had been disabled by his wound early in the battle, and thus did not participate in the victory, did not reduce the recognition given to him.[49] As a reward for his services, Parliament voted Johnson £5,000 and King George made him a baronet.[24] "Never was such an insignificant encounter so generously rewarded", wrote the historian Julian Gwyn.[50]

In January 1756, the British government made Johnson sole Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the northern colonies. This position gave him great influence and power, since he would report directly to the government in London and would not be controlled by provincial governments, as the Indian Department was a military one.[51] Of all the Indian nations in the northern colonies, Johnson was most knowledgeable about, and most closely connected to, the Iroquois Six Nations, especially the Mohawk. As superintendent, he would make the Iroquois the focus of British diplomacy, promoting and even exaggerating the power of the Iroquois Confederacy. Johnson also began a long process of trying to control Iroquois diplomacy, attempting "nothing less than the refurbishment of the Iroquois confederacy with himself as to its centre".[52]

Capture of Fort Niagara

editAlthough Johnson was no longer a British general, he continued to lead Iroquois and frontier militia. In August 1757, after the French began their siege of Fort William Henry, Johnson arrived at Fort Edward with 180 Indians and 1,500 militia.[53] Greatly overestimating the size of the French army, British General Daniel Webb decided against sending a relief force from Fort Edward to Fort William Henry. The British were compelled to surrender Fort William Henry, after which many were killed in an infamous massacre. Stories circulated that Johnson was enraged by Webb's decision not to send help, and that he stripped naked in front of Webb to express his disgust.[54]

With the war going badly for the British, Johnson found it difficult to enlist the support of the Six Nations, who were not eager to join a losing cause. In July 1758, he managed to raise 450 warriors to take part in a massive expedition led by the new British commander, General James Abercrombie.[55] The campaign ended ingloriously with Abercrombie's disastrous attempt to take Fort Carillon from the French. Johnson and his Indian auxiliaries could do little as British forces stormed the French positions in fruitless frontal assaults.[56]

In 1758, with the capture of Louisbourg, Fort Frontenac, and Fort Duquesne, the war's momentum began to shift in favour of the British.[58] Johnson was able to recruit more Iroquois warriors. In the summer of 1759, he led nearly 1,000 Iroquois warriors—practically the entire military strength of the Six Nations—as part of General John Prideaux's expedition to capture Fort Niagara.[59] When Prideaux was killed, Johnson took command.

He captured the fort after ambushing and defeating a French relief force at the Battle of La Belle-Famille. Johnson is usually credited with leading or at least planning this ambush,[60] but the historian Francis Jennings argued that Johnson was not present at the battle, and that he exaggerated his role in official dispatches.[24] The conquest of Niagara drove the French line back from the Great Lakes. Once more, Johnson was celebrated as a hero, although some professional soldiers expressed doubts about his military abilities and the value of the Iroquois in the victory.[61] Johnson commanded the "largest Native American force ever assembled under the British flag."[62]

Johnson accompanied General Jeffery Amherst in the final North American campaign of the Seven Years' War, the capture of Montreal in 1760. With the fall of New France to the British, Johnson and his deputy George Croghan spent much time negotiating with the former Indian allies of the French. In 1761, Johnson made a 1,000-mile (1,600 km) round trip to Detroit to hold a conference with the regional American Indians.[63] Johnson confronted the assembled chiefs about the anti-British rumours that were circulating among the Natives, and managed, for the time being, to forestall outright resistance to the British military occupation of the West.[64] Normand Macleod met Johnson at this conference and returned with him to New York. Macleod was later appointed as commander of Fort Oswego, on Lake Ontario.[65]

British Superintendent of Indian Affairs

editBecause of his knowledge of Iroquois language and customs and his success in business and governance, he was appointed the newly established British Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the northern district, serving from 1756 until his death in 1774. In this role, Johnson worked to keep American Indians attached to the British interest. Johnson's counterpart for the southern colonies was John Stuart.

Postwar development

editAfter the French and Indian War, Johnson hoped to concentrate on expanding and improving his land holdings.[66] In December 1760, the Mohawk of Canajoharie gave Johnson a tract of about 80,000 acres (320 km2) north of the Mohawk River.[67] This grant proved to be controversial because other land speculators had already obtained licenses to purchase lands that the Mohawk released for sale, but Sir William had not.[68] In 1769, after years of manoeuvring and lobbying, Johnson finally gained royal approval for the grant.[69] This was one of several large tracts of land that Johnson acquired from the Mohawk and Iroquois using his position as a royal Indian agent. By the time of his death, Johnson had accumulated about 170,000 acres (690 km2)[70] and was one of the largest land owners in British America, surpassed only by the Penn and van Rensselaer families.[citation needed] According to historian Julian Gwyn:

In all this he acted no differently from dozens of other speculators in Indian lands. He was distinguished only by the great advantages he possessed through his office and his long intimacy with the Indians. He was indeed one of their principal exploiters....[50]

In 1762, Johnson founded the city of Johnstown on his grant, about 25 miles (40 km) west of Schenectady, New York, north of the Mohawk River. He named the new settlement, originally called John's Town, after his son John. There, at the Crown expense,[50] he established a free school for both white and Mohawk children.[71]

Outside the town, in 1763 he built Johnson Hall, where he lived until his death. He recruited numerous Irish immigrant tenant farmers for his extensive lands, and lived essentially as a feudal landlord. He also purchased enslaved Africans to work as labourers, especially in his lumber operations. Johnson had some 60 slaves working for him, making him the largest slaveholder in the county and likely in the province, comparable to major planters in the American South.[72] In 1766, Johnson organised St. Patrick's Lodge, No. 4, a Freemason lodge, at Johnson Hall, and was installed as its master. His nephew Guy Johnson succeeded him as master of this lodge in 1770.[73]

Johnson was a strong supporter of the Anglican Church in the colony.[74] To counter the influence of French Catholic missionaries in western New York, in 1769 he paid for the construction of an Anglican church for the Mohawk of Canajoharie, a village the British called the "Upper Castle". The building, later used by European-American congregations and known as Indian Castle Church, still stands near Danube, New York. It is part of the Mohawk Upper Castle Historic District, a National Historic Landmark.[75][76] In 1771, Johnson built St. John's Episcopal Church in Johnstown, but soon complained that it was "small and very ill built." Within five years, he arranged for a larger church of stone to be constructed to accommodate the growing congregation in Johnstown. The historic church is still operating.[77]

Pontiac's War and final years

editIn 1763, Pontiac's War resulted from Native American discontent with British policy following the French and Indian War. For several years prior to the uprising, Johnson had advised General Jeffery Amherst to observe Iroquois diplomatic practices, for instance, awarding gifts to Native leaders, a practice they considered an important cultural symbol of respect and significant to maintaining good relations. Amherst, who rejected Johnson's advice, was recalled to London and replaced by General Thomas Gage. Amherst's recall strengthened Johnson's position, because a policy of compromise was required with the Indians, and this was Johnson's domain. Johnson negotiated a treaty with Pontiac in 1766, which finally ended the war.

From July to August 1764, Johnson negotiated a treaty at Fort Niagara with about 2,000 American Indians in attendance, primarily Iroquois. Although most Iroquois had stayed out of the war, the Seneca from the Genesee River valley had taken up arms against the British, and Johnson worked to bring them back into the Covenant Chain alliance. Johnson convinced the Iroquois to send a war party against the Seneca involved in the uprising, but otherwise the Iroquois did not contribute to the war effort as much as Johnson had desired.[79]

Johnson was a proponent of the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which called for tighter imperial control and restraint of westward colonial expansion. Johnson negotiated the details of the boundary defined in the Fort Stanwix Treaty of 1768. Against instructions from London, Johnson pushed the boundary 400 miles (640 km) to the west, enabling him and other land speculators to acquire much more land than originally authorised by the British government. Johnson was strongly criticised for exceeding his instructions, but many of the land speculators were well-connected in the government, and the expanded boundary was allowed to stand. During this time he became a member of the American Philosophical Society through his election to membership in 1768.[80]

Native American discontent continued to grow in the west in the 1770s. Johnson spent his final years attempting to prevent another uprising like Pontiac's War. Pursuing a policy of divide and rule, he worked to block the emergence of intertribal Native American alliances. His final success was his isolation of the Shawnee before Dunmore's War in 1774.

Marriage and family

editIn his lifetime, Johnson gained a reputation as a man who had numerous children with several European and Native American women.[81] At the time, men were not ostracised for having illegitimate children, as long as they could afford it and supported them. One 20th-century scholar estimated that Johnson had perhaps 100 illegitimate children,[82] but the historian Francis Jennings argued that "there is no truth in wild stories that he slept with innumerable Mohawk women."[24] In his will, Johnson acknowledged children by Catherine Weisenberg and Molly Brant, German and Mohawk, respectively, with whom he had long-term relationships. He implicitly acknowledged several other children by unnamed mothers.

In 1739, shortly after arriving in America, Johnson began a relationship with Catherine Weisenberg (c. 1723–1759), a German immigrant from the Electorate of the Palatinate. She originally came to the colonies as an indentured servant, but had run away, perhaps with the help of friends or relatives.[83] According to tradition, she was working for another family near Warrensburgh when Johnson purchased the remainder of her indenture contract, perhaps initially to have her serve as his housekeeper.[84] While there is no record that the couple ever formally married,[85] New York did not require civil marriage licenses or certificates to be filed at that time, and Weisenberg was Johnson's common-law wife.[24] The couple had three known children together, including daughters Nancy and Mary (Polly), and a son John, first christened only under the surname Weisenberg at Fort Hunter.[86] The senior Johnson later arranged for his son John to inherit his title and estates as John Johnson.[87] A grandson of Sir William Johnson was the 3rd Baronet Sir Adam Gordon Johnson who was, through his grandmother Ann Watts, a descendant of the Schuyler, Delancey, and Van Cortlandt families of British North America.[88]

At the same time, Johnson had a relationship with Elizabeth Brant, a Mohawk woman by whom he had three known children: Keghneghtago or Brant (born in 1742), Thomas (1744) and Christian (1745); the latter two boys died in infancy.[89] About 1750, Johnson had a son named Tagawirunta, also known as William of Canajoharie, by a Mohawk woman, possibly Margaret Brant, Elizabeth's younger sister.[90] Johnson may have also been intimate with the sisters Susannah and Elizabeth Wormwood, and an Irish woman named Mary McGrath by whom he appeared to have had a daughter named Mary.[91] Mary, Keghneghtago (Brant), and Tagawirunta (William) received inheritances in Johnson's will.[92]

In 1759, Johnson began a common-law relationship with Molly Brant, a Mohawk woman who lived with Johnson as his consort at Johnson Hall for the rest of his life. Molly was the older sister of Joseph Brant, who joined the household when he was young. Johnson's relationship with Molly gave him additional influence with the Mohawk. The couple had eight children together, all of whom received land from Johnson by his will.[93] A grandson of William Johnson and Molly Brant was William Johnson Kerr, who married Elizabeth Brant, a daughter of Joseph Brant and granddaughter of George Croghan and their Mohawk wives.

Death and legacy

editJohnson died from a stroke at Johnson Hall on 11 July 1774 during an Indian conference. Guy Johnson, William's nephew and son-in-law (he had married Mary/Polly), reported that Johnson died when he was "seized of a suffocation."[94] His funeral in Johnstown was attended by more than 2,000 people. His pallbearers included Governor William Franklin of New Jersey and the justices of the New York Supreme Court. He was buried beneath the altar in St. John's Episcopal church, the church he founded in Johnstown. The next day chiefs of the Six Nations performed the condolence ceremony and recognized Guy Johnson as Sir William's successor.[95]

During the American Revolution, the rebel New York legislature seized all of Johnson's lands and property, as his heirs were Loyalists.

Indian Relations

editJohnson's most important legacy is the comparatively peaceful co-existence of Anglo-Americans and Indians during his tenure as Indian Agent for British North America. As an adopted Mohawk chief and husband of Mohawk Mary (Molly) Brant, according to Iroquois law, he was a trusted counselor and member of the Mohawk nation. Through that affiliation, he was considered a member of the Six Nations of the Iroquois. That position gave him standing not only to lead Iroquois into battle on the side of the English, but also to negotiate two treaties of Fort Stanwix (which developed as modern-day Rome, New York). While the treaties deprived many Indians of land without their knowledge, they gave favorable terms to the Iroquois, and resulted in decades of comparative peace between traditional Indian residents and new settlers.

Co-existence was part of Johnson's other major historical legacy: the protection of British sovereignty and Anglo-American settlement as a bulwark against French control of northern New York and the Great Lakes region more generally. Johnson was instrumental in sustaining British-Iroquois alliance through the Covenant Chain, which consolidated both Iroquois and British territorial and commercial interests against the rival Algonquin and French interests in New France before 1763. After Britain assumed control of former French territories east of the Mississippi River, Johnson eventually won a political dispute over Indian policy with Lord Jeffery Amherst. He had disdained the Iroquois alliance which Johnson had so devoted himself to nurturing and defending. It was to Johnson that Pontiac finally surrendered after the eventual failure of the conflict named for him.

Structures

editOld Fort Johnson, his first home built in 1749, is on the Historic American Buildings Survey.[96] It is now used by the Montgomery County Historical Society, which operates a museum and gift shop there, as well as allowing it to be an event venue. Guy Park Manor, built in 1773, for Sir William's daughter Mary (Polly) and her husband, his nephew Guy Johnson, is also open to the public.

In 1960 Johnson Hall was named a National Historic Landmark. It is a designated State Historic Site and open to the public.

Papers

editA 1911 fire at the New York State Library damaged or destroyed a collection of about 6550 pieces of Johnson's papers. A 1921 publication of the papers collected from salvaged documents, other archives, and from an early printer's proof of his works exists for historians interested in studying Sir William.[97]

In popular culture

editThe Johnstown High School mascot is the "Sir Bill" in Johnson's honor (or "Lady Bill" for all-female teams). The teams' sportswear often depicts Johnson's silhouette, wearing a tricorne hat.[98]

Johnson appears as an antagonist as a secret member of the Templar Order in the 2012 video game Assassin's Creed III. He is instructed by the Templars to seize and control Native American lands and in retaliation he is killed by the game's Mohawk protagonist, Ratonhnhaké:ton.[99] He also makes an appearance in the 2014 video game prequel Assassin's Creed Rogue where he allies and helps mentor the game's protagonist, Shay Patrick Cormac.[100]

He is a prominent character in the 2007 book Manituana by Wu Ming. He also features in Robert Louis Stevenson's novel, The Master of Ballantrae (1889).

Johnson was portrayed by Chris Wiggins in the 1990 television film Divided Loyalties, and by Pierce Brosnan in the 1993 television movie The Broken Chain.[101]

Johnson was portrayed by actor Jeff Monahan in the PBS docudrama The War that Made America (2006). Monahan studied contemporary physical deportment and speaking in a northern Irish accent for the role.

Wilderness Empire (1968), by Allan W Eckert, tells Johnson's story through the device of historical fiction. Eckert bases his novel on historical documents but also creates imagined events and dialogs that make it accessible to the average reader.

Ancestors

edit| Ancestors of Sir William Johnson, 1st Baronet | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

editCitations

edit- ^ Flexner, James Thomas (1959). Mohawk Baronet: A Biography of Sir William Johnson. Syracuse University Press. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-8156-0239-2.

- ^ O'Toole, Fintan (2005). White Savage: William Johnson and the Invention of America. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-4668-9269-9.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), pp. 19–20.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 21.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 37Hamilton, Milton W. (1976). Sir William Johnson: Colonial American, 1715–1763. Port Washington, New York: Kennikat. pp. xi–xii, 5. ISBN 0-8046-9134-7.. The first of what was intended to be a two-volume biography; Hamilton never completed the second.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 25.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 36.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 38.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), pp. 37–38.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 41.

- ^ Hamilton (1976), p. 36; O'Toole (2005), p. 291

- ^ O'Toole (2005), pp. 41–42.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 68.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 43.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 65.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 69.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 72.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 73; Hamilton (1976), p. 55

- ^ Shannon, Timothy John (2008). Iroquois Diplomacy on the Early American Frontier. Viking. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-670-01897-0.

- ^ Shannon (2008), p. 122.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 79; Hamilton (1976), p. 56

- ^ O'Toole (2005), pp. 80–81.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 86.

- ^ a b c d e Jennings, Francis (February 2000). "Johnson, Sir William". American National Biography. New York: Oxford University Press. (subscription required)

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 110; Hamilton (1976), p. 37

- ^ Hamilton (1976), pp. 69–70.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 89.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), pp. 90–95.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 123.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 161.

- ^ Hamilton (1976), p. 41.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 96; Shannon (2008), pp. 103–105, 123

- ^ Shannon (2008), p. 138.

- ^ Shannon (2008), pp. 139–140.

- ^ Shannon (2008), p. 143; O'Toole (2005), p. 112

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 112-113.

- ^ Hamilton (1976), p. 120.

- ^ Hamilton (1976), pp. 120–21; O'Toole (2005), p. 129

- ^ Hamilton (1976), p. 132.

- ^ Hamilton (1976), ch. 14, and 328–329.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 135.

- ^ Flexner (1959), p. 124; Hamilton (1976), p. 165; O'Toole (2005), p. 142

- ^ O'Toole (2005), pp. 142–143.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), pp. 146, 151.

- ^ Hamilton (1976), p. 186; O'Toole (2005), p. 152

- ^ Hamilton (1976), p. 190.

- ^ Hamilton (1976), pp. 194–195.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 152.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), pp. 149, 154–155.

- ^ a b c Gwyn, Julian (1979). "Johnson, Sir William". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. IV (1771–1800) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), pp. 153–154.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), pp. 158–165.

- ^ Hamilton (1976), p. 225; O'Toole (2005), p. 188

- ^ O'Toole (2005), pp. 189–190.

- ^ Hamilton (1976), p. 233.

- ^ Hamilton (1976), p. 236.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), pp. 239–240.

- ^ Hamilton (1976), p. 241.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 203.

- ^ Flexner (1959), p. 207; O'Toole (2005), pp. 205–206

- ^ Flexner (1959), p. 215; Hamilton (1976), pp. 261–262

- ^ "Nomination of Johnson Hall to the National Register of Historic Places". National Park Service. 15 October 1984.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 221.

- ^ Hamilton (1976), pp. 283–296; O'Toole (2005), pp. 226–228

- ^ Macleod, Normand. Detroit to Fort Sackville, 1778–1779. Detroit: Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Free Library, 1778, pp. viii–xiii

- ^ Hamilton (1976), p. 297.

- ^ Hamilton (1976), pp. 299, 376n18; O'Toole (2005), pp. 176–177

- ^ Hamilton (1976), p. 300.

- ^ Hamilton (1976), p. 301.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), pp. 281–282.

- ^ Decker, Lewis G. (1999). Johnstown. Images of America. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-7385-0174-1.

- ^ Williams-Myers, Albert James (1994). Long hammering: essays on the forging of an African American presence in the Hudson River Valley to the early twentieth century. Africa World Press. pp. 24, 29–30. ISBN 978-0-86543-302-1.

- ^ Pound, Arthur; Day, Richard Edwin (1930). Johnson of the Mohawks: A Biography of Sir William Johnson, Irish Immigrant, Mohawk War Chief, American Soldier, Empire Builder. New York: Macmillan. p. 447.

- ^ Taylor, Alan (10 September 2006). "The Collaborator". The New Republic.

- ^ Pound & Day (1930), p. 446.

- ^ Snow, Dean R.; Guldenzopf, David B. "Indian Castle Church". Archived from the original on 22 June 2006. Retrieved 23 August 2009.

- ^ Flexner (1959), p. 301.

- ^ Johnson Papers, vol. 2, v–xii, 160. See also Revealing the Light: Mezzotint Engravings at Georgetown University, from the Georgetown University Library.

- ^ For Niagara treaty, see McConnell, A Country Between, 197–99; Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 219–20, 228; Dowd, War under Heaven, 151–53.

- ^ Bell, Whitfield J., and Charles Greifenstein, Jr. Patriot-Improvers: Biographical Sketches of Members of the American Philosophical Society. 3 vols. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1997, 3:580–586.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 104.

- ^ Wallace, Paul A. W. (1971). Conrad Weiser, 1696-1760, Friend of Colonist and Mohawk. Russell & Russell. p. 247., quoted in Jennings, Francis (1988). Empire of Fortune: Crowns, Colonies, and Tribes in the Seven Years War in America. Norton. pp. 77: note 13. ISBN 978-0-393-30640-8.

- ^ Hamilton (1976), pp. 33–34.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), pp. 44–46.

- ^ Hamilton (1976), p. 34.

- ^ Bazely, Susan M. (17 September 1996). "Who Was Molly Brant?". Kingston Historical Society. Cataraqui Archaeological Research Foundation. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ^ Pound & Day (1930), p. 48.

- ^ Wells, Albert. Watts (Watt), in New York and in Edinburgh, Scotland. Also Watts, Wattes, Wattys, Wathes, de Wath, Le Fleming, (in England.) 1898

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 105.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 106.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), pp. 106–108.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), pp. 106, 108.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 174.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 323.

- ^ O'Toole (2005), p. 324; For more on Johnson's Iroquois funeral, see William N. Fenton, The Great Law and the Longhouse: A Political History of the Iroquois Confederacy (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1998; ISBN 0-8061-3003-2), 570–72.

- ^ "Fort Johnson". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. 15 September 2007. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011.

- ^ The papers of Sir William Johnson. Albany : University of the State of New York. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ "Back to School '16" (PDF). The Caesar Rodney School District Quarterly. Caesar Rodney School District: 15. 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ Costiuc, Stanislav (28 July 2016). "Open-world mission design learnings from Assassin's Creed III". Gamasutra. UBM plc. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ Lewis, Anne (13 October 2014). "Assassin's Creed Rogue - Faces of Shay". Ubiblog. Ubisoft Entertainment. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ Voros, Drew (12 December 1993). "The Broken Chain". Variety. Penske Business Media, LLC. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

General References

edit- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 472.

- Chichester, Henry Manners (1892). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 30. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 50–52.

- Reynolds, Francis J., ed. (1921). . Collier's New Encyclopedia. New York: P. F. Collier & Son Company.

- Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

Further reading

edit"More on Sir William Johnson" (PDF). The American Fly Fisher. 11 (2). Manchester, VT: American Museum of Fly Fishing: 2–6. Spring 1984. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 19 November 2014.

External links

edit- Sir William Johnson, 1715-1774 - Papers, 1738-1808 (finding aid) at the New York State Library, accessed May 18, 2016.

- Johnson Hall State Historic Site Archived 5 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Fort Johnson Historic Landmark

- Sir William Johnson, 1st Baronet at Find a Grave

- Sir William Johnson Letters at the Newberry Library

- References to Sir William Johnson in Haldimand Collection (Papers)

- Robert Adems's 'Daybok' 1768—1773, recording purchases of daily goods made by Johnson's household between the years 1768–1773. A transcription (by Dr. Michael D. Elliot) of Hamilton's 1962 edition.