Genetic recombination (also known as genetic reshuffling) is the exchange of genetic material between different organisms which leads to production of offspring with combinations of traits that differ from those found in either parent. In eukaryotes, genetic recombination during meiosis can lead to a novel set of genetic information that can be further passed on from parents to offspring. Most recombination occurs naturally and can be classified into two types: (1) interchromosomal recombination, occurring through independent assortment of alleles whose loci are on different but homologous chromosomes (random orientation of pairs of homologous chromosomes in meiosis I); & (2) intrachromosomal recombination, occurring through crossing over.[1]

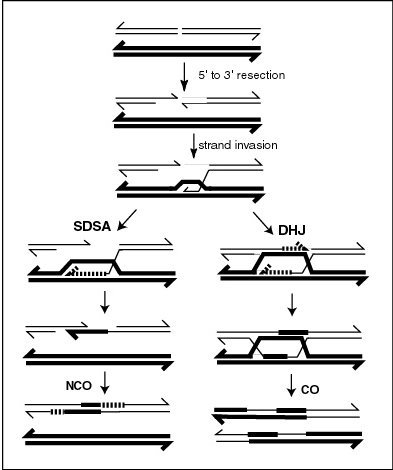

During meiosis in eukaryotes, genetic recombination involves the pairing of homologous chromosomes. This may be followed by information transfer between the chromosomes. The information transfer may occur without physical exchange (a section of genetic material is copied from one chromosome to another, without the donating chromosome being changed) (see SDSA – Synthesis Dependent Strand Annealing pathway in Figure); or by the breaking and rejoining of DNA strands, which forms new molecules of DNA (see DHJ pathway in Figure).

Recombination may also occur during mitosis in eukaryotes where it ordinarily involves the two sister chromosomes formed after chromosomal replication. In this case, new combinations of alleles are not produced since the sister chromosomes are usually identical. In meiosis and mitosis, recombination occurs between similar molecules of DNA (homologous sequences). In meiosis, non-sister homologous chromosomes pair with each other so that recombination characteristically occurs between non-sister homologues. In both meiotic and mitotic cells, recombination between homologous chromosomes is a common mechanism used in DNA repair.

Gene conversion – the process during which homologous sequences are made identical also falls under genetic recombination.

Genetic recombination and recombinational DNA repair also occurs in bacteria and archaea, which use asexual reproduction.

Recombination can be artificially induced in laboratory (in vitro) settings, producing recombinant DNA for purposes including vaccine development.

V(D)J recombination in organisms with an adaptive immune system is a type of site-specific genetic recombination that helps immune cells rapidly diversify to recognize and adapt to new pathogens.

Synapsis

editDuring meiosis, synapsis (the pairing of homologous chromosomes) ordinarily precedes genetic recombination.

Mechanism

editGenetic recombination is catalyzed by many different enzymes. Recombinases are key enzymes that catalyse the strand transfer step during recombination. RecA, the chief recombinase found in Escherichia coli, is responsible for the repair of DNA double strand breaks (DSBs). In yeast and other eukaryotic organisms there are two recombinases required for repairing DSBs. The RAD51 protein is required for mitotic and meiotic recombination, whereas the DNA repair protein, DMC1, is specific to meiotic recombination. In the archaea, the ortholog of the bacterial RecA protein is RadA.

- Bacterial recombination

In bacteria there is regular genetic recombination, as well as ineffective transfer of genetic material, expressed as unsuccessful transfer or abortive transfer, which is any bacterial DNA transfer of the donor cell to recipients which have set the incoming DNA as part of the genetic material of the recipient.[citation needed][clarification needed] Abortive transfer was registered in the following transduction and conjugation.[clarification needed] In all cases, the transmitted fragment is diluted by the culture growth.[2][3][4]

Chromosomal crossover

editIn eukaryotes, recombination during meiosis is facilitated by chromosomal crossover. The crossover process leads to offspring having different combinations of genes from those of their parents, and can occasionally produce new chimeric alleles.[citation needed] The shuffling of genes brought about by genetic recombination produces increased genetic variation. It also allows sexually reproducing organisms to avoid Muller's ratchet, in which the genomes of an asexual population tend to accumulate more deleterious mutations over time than beneficial or reversing mutations.[citation needed]

Chromosomal crossover involves recombination between the paired chromosomes inherited from each of one's parents, generally occurring during meiosis.[citation needed] During prophase I (pachytene stage) the four available chromatids are in tight formation with one another.[citation needed] While in this formation, homologous sites on two chromatids can closely pair with one another, and may exchange genetic information.[5]

Because there is a small probability of recombination at any location along a chromosome, the frequency of recombination between two locations depends on the distance separating them.[citation needed] Therefore, for genes sufficiently distant on the same chromosome, the amount of crossover is high enough to destroy the correlation between alleles.[citation needed]

Tracking the movement of genes resulting from crossovers has proven quite useful to geneticists. Because two genes that are close together are less likely to become separated than genes that are farther apart, geneticists can deduce roughly how far apart two genes are on a chromosome if they know the frequency of the crossovers.[citation needed] Geneticists can also use this method to infer the presence of certain genes. Genes that typically stay together during recombination are said to be linked. One gene in a linked pair can sometimes be used as a marker to deduce the presence of the other gene. This is typically used to detect the presence of a disease-causing gene.[6]

The recombination frequency between two loci observed is the crossing-over value. It is the frequency of crossing over between two linked gene loci (markers), and depends on the distance between the genetic loci observed. For any fixed set of genetic and environmental conditions, recombination in a particular region of a linkage structure (chromosome) tends to be constant, and the same is then true for the crossing-over value which is used in the production of genetic maps.[2][7]

Gene conversion

editIn gene conversion, a section of genetic material is copied from one chromosome to another, without the donating chromosome being changed. Gene conversion occurs at high frequency at the actual site of the recombination event during meiosis. It is a process by which a DNA sequence is copied from one DNA helix (which remains unchanged) to another DNA helix, whose sequence is altered. Gene conversion has often been studied in fungal crosses[8] where the 4 products of individual meioses can be conveniently observed. Gene conversion events can be distinguished as deviations in an individual meiosis from the normal 2:2 segregation pattern (e.g. a 3:1 pattern).

Nonhomologous recombination

editRecombination can occur between DNA sequences that contain no sequence homology. This can cause chromosomal translocations, sometimes leading to cancer.

In B cells

editB cells of the immune system perform genetic recombination, called immunoglobulin class switching. It is a biological mechanism that changes an antibody from one class to another, for example, from an isotype called IgM to an isotype called IgG.

Genetic engineering

editIn genetic engineering, recombination can also refer to artificial and deliberate recombination of disparate pieces of DNA, often from different organisms, creating what is called recombinant DNA. A prime example of such a use of genetic recombination is gene targeting, which can be used to add, delete or otherwise change an organism's genes. This technique is important to biomedical researchers as it allows them to study the effects of specific genes. Techniques based on genetic recombination are also applied in protein engineering to develop new proteins of biological interest.

Examples include Restriction enzyme mediated integration, Gibson assembly and Golden Gate Cloning.

Recombinational repair

editDNA damages caused by a variety of exogenous agents (e.g. UV light, X-rays, chemical cross-linking agents) can be repaired by homologous recombinational repair (HRR).[9][10] These findings suggest that DNA damages arising from natural processes, such as exposure to reactive oxygen species that are byproducts of normal metabolism, are also repaired by HRR. In humans, deficiencies in the gene products necessary for HRR during meiosis likely cause infertility[11] In humans, deficiencies in gene products necessary for HRR, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2, increase the risk of cancer (see DNA repair-deficiency disorder).

In bacteria, transformation is a process of gene transfer that ordinarily occurs between individual cells of the same bacterial species. Transformation involves integration of donor DNA into the recipient chromosome by recombination. This process appears to be an adaptation for repairing DNA damages in the recipient chromosome by HRR.[12] Transformation may provide a benefit to pathogenic bacteria by allowing repair of DNA damage, particularly damages that occur in the inflammatory, oxidizing environment associated with infection of a host.

When two or more viruses, each containing lethal genomic damages, infect the same host cell, the virus genomes can often pair with each other and undergo HRR to produce viable progeny. This process, referred to as multiplicity reactivation, has been studied in lambda and T4 bacteriophages,[13] as well as in several pathogenic viruses. In the case of pathogenic viruses, multiplicity reactivation may be an adaptive benefit to the virus since it allows the repair of DNA damages caused by exposure to the oxidizing environment produced during host infection.[12] See also reassortment.

Meiotic recombination

editA molecular model for the mechanism of meiotic recombination presented by Anderson and Sekelsky[14] is outlined in the first figure in this article. Two of the four chromatids present early in meiosis (prophase I) are paired with each other and able to interact. Recombination, in this model, is initiated by a double-strand break (or gap) shown in the DNA molecule (chromatid) at the top of the figure. Other types of DNA damage may also initiate recombination. For instance, an inter-strand cross-link (caused by exposure to a cross-linking agent such as mitomycin C) can be repaired by HRR.

Two types of recombinant product are produced. Indicated on the right side is a "crossover" (CO) type, where the flanking regions of the chromosomes are exchanged, and on the left side, a "non-crossover" (NCO) type where the flanking regions are not exchanged. The CO type of recombination involves the intermediate formation of two "Holliday junctions" indicated in the lower right of the figure by two X-shaped structures in each of which there is an exchange of single strands between the two participating chromatids. This pathway is labeled in the figure as the DHJ (double-Holliday junction) pathway.

The NCO recombinants (illustrated on the left in the figure) are produced by a process referred to as "synthesis dependent strand annealing" (SDSA). Recombination events of the NCO/SDSA type appear to be more common than the CO/DHJ type.[15] The NCO/SDSA pathway contributes little to genetic variation, since the arms of the chromosomes flanking the recombination event remain in the parental configuration. Thus, explanations for the adaptive function of meiosis that focus exclusively on crossing-over are inadequate to explain the majority of recombination events.

Achiasmy and heterochiasmy

editAchiasmy is the phenomenon where autosomal recombination is completely absent in one sex of a species. Achiasmatic chromosomal segregation is well documented in male Drosophila melanogaster. The "Haldane-Huxley rule" states that achiasmy usually occurs in the heterogametic sex.[16]

Heterochiasmy occurs when recombination rates differ between the sexes of a species.[16] In humans, each oocyte has on average 41.6 ± 11.3 recombinations, 1.63-fold higher than sperms. This sexual dimorphic pattern in recombination rate has been observed in many species. In mammals, females most often have higher rates of recombination. [17]

RNA virus recombination

editNumerous RNA viruses are capable of genetic recombination when at least two viral genomes are present in the same host cell.[18][19] Recombination is largely responsible for RNA virus diversity and immune evasion.[20] RNA recombination appears to be a major driving force in determining genome architecture and the course of viral evolution among picornaviridae ((+)ssRNA) (e.g. poliovirus).[21] In the retroviridae ((+)ssRNA)(e.g. HIV), damage in the RNA genome appears to be avoided during reverse transcription by strand switching, a form of recombination.[22][23]

Recombination also occurs in the reoviridae (dsRNA)(e.g. reovirus), orthomyxoviridae ((-)ssRNA)(e.g. influenza virus)[23] and coronaviridae ((+)ssRNA) (e.g. SARS).[24][25]

Recombination in RNA viruses appears to be an adaptation for coping with genome damage.[18] Switching between template strands during genome replication, referred to as copy-choice recombination, was originally proposed to explain the positive correlation of recombination events over short distances in organisms with a DNA genome (see first Figure, SDSA pathway).[26]

Recombination can occur infrequently between animal viruses of the same species but of divergent lineages. The resulting recombinant viruses may sometimes cause an outbreak of infection in humans.[24]

Especially in coronaviruses, recombination may also occur even among distantly related evolutionary groups (subgenera), due to their characteristic transcription mechanism, that involves subgenomic mRNAs that are formed by template switching.[27][25]

When replicating its (+)ssRNA genome, the poliovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) is able to carry out recombination. Recombination appears to occur by a copy choice mechanism in which the RdRp switches (+)ssRNA templates during negative strand synthesis.[28] Recombination by RdRp strand switching also occurs in the (+)ssRNA plant carmoviruses and tombusviruses.[29]

Recombination appears to be a major driving force in determining genetic variability within coronaviruses, as well as the ability of coronavirus species to jump from one host to another and, infrequently, for the emergence of novel species, although the mechanism of recombination in is unclear.[24]

In early 2020, many genomic sequences of Australian SARS‐CoV‐2 isolates have deletions or mutations (29742G>A or 29742G>U; "G19A" or "G19U") in the s2m, suggesting that RNA recombination may have occurred in this RNA element. 29742G("G19"), 29744G("G21"), and 29751G("G28") were predicted as recombination hotspots.[30] During the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic, such a recombination event was suggested to have been a critical step in the evolution of SARS-CoV-2's ability to infect humans.[31] Linkage disequilibrium analysis confirmed that RNA recombination with the 11083G > T mutation also contributed to the increase of mutations among the viral progeny. The findings indicate that the 11083G > T mutation of SARS-CoV-2 spread during Diamond Princess shipboard quarantine and arose through de novo RNA recombination under positive selection pressure. In three patients on the Diamond Princess cruise, two mutations, 29736G > T and 29751G > T (G13 and G28) were located in Coronavirus 3′ stem-loop II-like motif (s2m) of SARS-CoV-2. Although s2m is considered an RNA motif highly conserved in 3' untranslated region among many coronavirus species, this result also suggests that s2m of SARS-CoV-2 is RNA recombination/mutation hotspot.[32]

SARS-CoV-2's entire receptor binding motif appeared, based on preliminary observations, to have been introduced through recombination from coronaviruses of pangolins.[33] However, more comprehensive analyses later refuted this suggestion and showed that SARS-CoV-2 likely evolved solely within bats and with little or no recombination.[34][35]

Role of recombination in the origin of life

editNowak and Ohtsuki[36] noted that the origin of life (abiogenesis) is also the origin of biological evolution. They pointed out that all known life on earth is based on biopolymers and proposed that any theory for the origin of life must involve biological polymers that act as information carriers and catalysts. Lehman[37] argued that recombination was an evolutionary development as ancient as the origins of life. Smail et al.[38] proposed that in the primordial Earth, recombination played a key role in the expansion of the initially short informational polymers (presumed to be RNA) that were the precursors to life.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Daly, M J; Minton, K W (October 1995). "Interchromosomal recombination in the extremely radioresistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans". Journal of Bacteriology. 177 (19): 5495–5505. doi:10.1128/jb.177.19.5495-5505.1995. ISSN 0021-9193. PMC 177357. PMID 7559335.

- ^ a b Rieger R, Michaelis A, Green MM (1976). Glossary of genetics and cytogenetics: Classical and molecular. Heidelberg – New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-07668-1.

- ^ King RC, Stransfield WD (1998). Dictionary of genetics. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-50944-1-1.

- ^ Bajrović K, Jevrić-Čaušević A, Hadžiselimović R, eds. (2005). Uvod u genetičko inženjerstvo i biotehnologiju. Institut za genetičko inženjerstvo i biotehnologiju (INGEB) Sarajevo. ISBN 978-9958-9344-1-4.

- ^ Alberts B (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell, Fourth Edition. New York: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-3218-3.

- ^ "Access Excellence". Crossing-over: Genetic Recombination. The National Health Museum Resource Center. Retrieved February 23, 2011.

- ^ King RC, Stransfield WD (1998). Dictionary of Genetics. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509442-5.

- ^ Stacey KA (1994). "Recombination". In Kendrew J, Lawrence E (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Molecular Biology. Oxford: Blackwell Science. pp. 945–950.

- ^ Baker BS, Boyd JB, Carpenter AT, Green MM, Nguyen TD, Ripoll P, Smith PD (November 1976). "Genetic controls of meiotic recombination and somatic DNA metabolism in Drosophila melanogaster". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 73 (11): 4140–4. Bibcode:1976PNAS...73.4140B. doi:10.1073/pnas.73.11.4140. PMC 431359. PMID 825857.

- ^ Boyd JB (1978). "DNA repair in Drosophila". In Hanawalt PC, Friedberg EC, Fox CF (eds.). DNA Repair Mechanisms. New York: Academic Press. pp. 449–452.

- ^ Galetzka D, Weis E, Kohlschmidt N, Bitz O, Stein R, Haaf T (April 2007). "Expression of somatic DNA repair genes in human testes". Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 100 (5): 1232–9. doi:10.1002/jcb.21113. PMID 17177185. S2CID 23743474.

- ^ a b Michod RE, Bernstein H, Nedelcu AM (May 2008). "Adaptive value of sex in microbial pathogens" (PDF). Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 8 (3): 267–85. Bibcode:2008InfGE...8..267M. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2008.01.002. PMID 18295550.

- ^ Bernstein C (March 1981). "Deoxyribonucleic acid repair in bacteriophage". Microbiological Reviews. 45 (1): 72–98. doi:10.1128/MMBR.45.1.72-98.1981. PMC 281499. PMID 6261109.

- ^ Andersen SL, Sekelsky J (December 2010). "Meiotic versus mitotic recombination: two different routes for double-strand break repair: the different functions of meiotic versus mitotic DSB repair are reflected in different pathway usage and different outcomes". BioEssays. 32 (12): 1058–66. doi:10.1002/bies.201000087. PMC 3090628. PMID 20967781.

- ^ Mehrotra, S.; McKim, K. S. (2006). "Temporal Analysis of Meiotic DNA Double-Strand Break Formation and Repair in Drosophila Females". PLOS Genetics. 2 (11): e200. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0020200. PMC 1657055. PMID 17166055.

- ^ a b Lenormand T (February 2003). "The evolution of sex dimorphism in recombination". Genetics. 163 (2): 811–22. doi:10.1093/genetics/163.2.811. PMC 1462442. PMID 12618416.

- ^ Ottolini, Christian S.; Newnham, Louise J.; Capalbo, Antonio; Natesan, Senthilkumar A.; Joshi, Hrishikesh A.; Cimadomo, Danilo; Griffin, Darren K.; Sage, Karen; Summers, Michael C.; Thornhill, Alan R.; Housworth, Elizabeth; Herbert, Alex D.; Rienzi, Laura; Ubaldi, Filippo M.; Handyside, Alan H. (July 2015). "Genome-wide maps of recombination and chromosome segregation in human oocytes and embryos show selection for maternal recombination rates". Nature Genetics. 47 (7): 727–735. doi:10.1038/ng.3306. ISSN 1546-1718. PMC 4770575. PMID 25985139.

- ^ a b Barr JN, Fearns R (June 2010). "How RNA viruses maintain their genome integrity". The Journal of General Virology. 91 (Pt 6): 1373–87. doi:10.1099/vir.0.020818-0. PMID 20335491.

- ^ Simon-Loriere, Etienne; Holmes, Edward C. (August 2011). "Why do RNA viruses recombine?". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 9 (8): 617–626. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2614. ISSN 1740-1526. PMC 3324781. PMID 21725337.

- ^ Rawson JM, Nikolaitchik OA, Keele BF, Pathak VK, Hu WS (November 2018). "Recombination is required for efficient HIV-1 replication and the maintenance of viral genome integrity". Nucleic Acids Research. 46 (20): 10535–10545. doi:10.1093/nar/gky910. PMC 6237782. PMID 30307534.

- ^ Muslin C, Mac Kain A, Bessaud M, Blondel B, Delpeyroux F (September 2019). "Recombination in Enteroviruses, a Multi-Step Modular Evolutionary Process". Viruses. 11 (9): 859. doi:10.3390/v11090859. PMC 6784155. PMID 31540135.

- ^ Hu WS, Temin HM (November 1990). "Retroviral recombination and reverse transcription". Science. 250 (4985): 1227–33. Bibcode:1990Sci...250.1227H. doi:10.1126/science.1700865. PMID 1700865.

- ^ a b Bernstein H, Bernstein C, Michod RE (January 2018). "Sex in microbial pathogens". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 57: 8–25. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2017.10.024. PMID 29111273.

- ^ a b c Su S, Wong G, Shi W, Liu J, Lai AC, Zhou J, Liu W, Bi Y, Gao GF (June 2016). "Epidemiology, Genetic Recombination, and Pathogenesis of Coronaviruses". Trends in Microbiology. 24 (6): 490–502. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2016.03.003. PMC 7125511. PMID 27012512.

- ^ a b Nikolaidis, Marios; Markoulatos, Panayotis; Van de Peer, Yves; Oliver, Stephen G; Amoutzias, Grigorios D (2021-10-12). Hepp, Crystal (ed.). "The neighborhood of the Spike gene is a hotspot for modular intertypic homologous and non-homologous recombination in Coronavirus genomes". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 39: msab292. doi:10.1093/molbev/msab292. ISSN 0737-4038. PMC 8549283. PMID 34638137.

- ^ Bernstein H (1962). "On the mechanism of intragenic recombination. I. The rII region of bacteriophage T4". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 3 (3): 335–353. Bibcode:1962JThBi...3..335B. doi:10.1016/S0022-5193(62)80030-7.

- ^ Graham, Rachel L.; Deming, Damon J.; Deming, Meagan E.; Yount, Boyd L.; Baric, Ralph S. (December 2018). "Evaluation of a recombination-resistant coronavirus as a broadly applicable, rapidly implementable vaccine platform". Communications Biology. 1 (1): 179. doi:10.1038/s42003-018-0175-7. ISSN 2399-3642. PMC 6206136. PMID 30393776.

- ^ Kirkegaard K, Baltimore D (November 1986). "The mechanism of RNA recombination in poliovirus". Cell. 47 (3): 433–43. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(86)90600-8. PMC 7133339. PMID 3021340.

- ^ Cheng CP, Nagy PD (November 2003). "Mechanism of RNA recombination in carmo- and tombusviruses: evidence for template switching by the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase in vitro". Journal of Virology. 77 (22): 12033–47. doi:10.1128/jvi.77.22.12033-12047.2003. PMC 254248. PMID 14581540.

- ^ Yeh TY, Contreras GP (July 2020). "Emerging viral mutants in Australia suggest RNA recombination event in the SARS-CoV-2 genome". The Medical Journal of Australia. 213 (1): 44–44.e1. doi:10.5694/mja2.50657. PMC 7300921. PMID 32506536.

- ^ Wang H, Pipes L, Nielsen R (2020-10-12). "Synonymous mutations and the molecular evolution of SARS-Cov-2 origins". bioRxiv 10.1101/2020.04.20.052019.

- ^ Yeh TY, Contreras GP (1 July 2021). "Viral transmission and evolution dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 in shipboard quarantine". Bull. World Health Organ. 99 (7): 486–495. doi:10.2471/BLT.20.255752. PMC 8243027. PMID 34248221.

- ^ Li X, Giorgi EE, Marichannegowda MH, Foley B, Xiao C, Kong XP, Chen Y, Gnanakaran S, Korber B, Gao F (July 2020). "Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 through recombination and strong purifying selection". Science Advances. 6 (27): eabb9153. Bibcode:2020SciA....6.9153L. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abb9153. PMC 7458444. PMID 32937441.

- ^ Boni MF, Lemey P, Jiang X, Lam TT, Perry BW, Castoe TA, et al. (November 2020). "Evolutionary origins of the SARS-CoV-2 sarbecovirus lineage responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic". Nature Microbiology. 5 (11): 1408–1417. doi:10.1038/s41564-020-0771-4. hdl:20.500.11820/222bb9b9-2481-4086-bd22-f0b200930bef. PMID 32724171.

- ^ Neches RY, McGee MD, Kyrpides NC (November 2020). "Recombination should not be an afterthought". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 18 (11): 606. doi:10.1038/s41579-020-00451-1. PMC 7503439. PMID 32958891.

- ^ Nowak, Martin A.; Ohtsuki, Hisashi (2008-09-30). "Prevolutionary dynamics and the origin of evolution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (39): 14924–14927. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10514924N. doi:10.1073/pnas.0806714105. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2567469. PMID 18791073.

- ^ Lehman, Niles (2003). "A Case for the Extreme Antiquity of Recombination". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 56 (6): 770–777. Bibcode:2003JMolE..56..770L. doi:10.1007/s00239-003-2454-1. PMID 12911039. S2CID 33130898.

- ^ Smail, Benedict A.; Clifton, Bryce E.; Mizuuchi, Ryo; Lehman, Niles (2019). "Spontaneous advent of genetic diversity in RNA populations through multiple recombination mechanisms". RNA. 25 (4): 453–464. doi:10.1261/rna.068908.118. PMC 642629. PMID 30670484.

External links

edit- Animations – homologous recombination: Animations showing several models of homologous recombination

- The Holliday Model of Genetic Recombination

- Genetic+recombination at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Animated guide to homologous recombination.

This article incorporates public domain material from Science Primer. NCBI. Archived from the original on 2009-12-08.