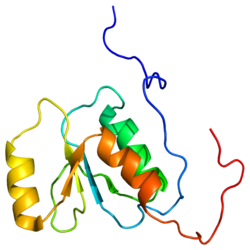

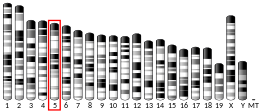

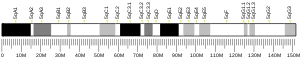

Replication factor C subunit 1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the RFC1 gene.[5][6]

Function

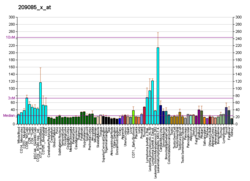

editThe protein encoded by this gene is the large subunit of replication factor C, which is a five subunit DNA polymerase accessory protein. Replication factor C is a DNA-dependent ATPase that is required for eukaryotic DNA replication and repair. The protein acts as an activator of DNA polymerases, binds to the 3' end of primers, and promotes coordinated synthesis of both strands. It also may have a role in telomere stability.[6]

Interactions

editRFC1 has been shown to interact with:

Clinical relevance

editBiallelic intronic repeat expansions (a series of repeating nucleotide sequences) in the replication factor C subunit 1 (RFC1) gene causes cerebellar ataxia, neuropathy and vestibular areflexia syndrome (CANVAS).[17] Within the poly(A) tail of an AluSx3 element in RFC1, there are eleven repeats of the pentanucleotide "AAAAG". Repeat expansion and polymorphic configuration are observed in part of the population, with increased number of repeats associated to alternative "AAAGG", "AAGGG" and "ACAGG" pentanucleotides.[18] In particular, biallelic "AAGGG" and "ACAGG" repeat expansion have disproportionately been observed in patients with CANVAS. Biallelic "AAGGG" repeat expansion is also reported in a high number of sporadic cases of late-onset ataxia,[17] isolate sensory neuropathy[19][20] and, less frequently, isolate cerebellar ataxia.[21] Due to a diagnostic overlap with CANVAS, researchers have also investigated the presence of RFC1 expansions in pathologically confirmed multiple system atrophy (MSA) but found a similar alteration frequency (0.7%) to a healthy population, suggesting RFC1 does not have a role in this disease.[22]

Mutant biallelic intronic repeat expansions do not affect RFC1 expression in patient peripheral and brain tissue, suggesting no overt loss of function of this gene.[17]

In patients with the pathogenic RFC1 expansion, sensory neuropathy appears to be a predominant feature and patients may also present with symptoms such as cerebellar dysfunction, vestibular involvement and a dry spasmodic cough therefore, genetic testing is recommended in those with these symptoms.[23]

References

edit- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000035928 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000029191 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Luckow B, Bunz F, Stillman B, Lichter P, Schütz G (March 1994). "Cloning, expression, and chromosomal localization of the 140-kilodalton subunit of replication factor C from mice and humans". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 14 (3): 1626–34. doi:10.1128/mcb.14.3.1626. PMC 358521. PMID 8114700.

- ^ a b "Entrez Gene: RFC1 replication factor C (activator 1) 1, 145kDa".

- ^ a b Maruyama T, Farina A, Dey A, Cheong J, Bermudez VP, Tamura T, et al. (September 2002). "A Mammalian bromodomain protein, brd4, interacts with replication factor C and inhibits progression to S phase". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 22 (18): 6509–20. doi:10.1128/mcb.22.18.6509-6520.2002. PMC 135621. PMID 12192049.

- ^ Anderson LA, Perkins ND (August 2002). "The large subunit of replication factor C interacts with the histone deacetylase, HDAC1". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (33): 29550–4. doi:10.1074/jbc.M200513200. PMID 12045192.

- ^ Fotedar R, Mossi R, Fitzgerald P, Rousselle T, Maga G, Brickner H, et al. (August 1996). "A conserved domain of the large subunit of replication factor C binds PCNA and acts like a dominant negative inhibitor of DNA replication in mammalian cells". The EMBO Journal. 15 (16): 4423–33. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00815.x. PMC 452166. PMID 8861969.

- ^ Mossi R, Jónsson ZO, Allen BL, Hardin SH, Hübscher U (January 1997). "Replication factor C interacts with the C-terminal side of proliferating cell nuclear antigen". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (3): 1769–76. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.3.1769. PMID 8999859.

- ^ van der Kuip H, Carius B, Haque SJ, Williams BR, Huber C, Fischer T (April 1999). "The DNA-binding subunit p140 of replication factor C is upregulated in cycling cells and associates with G1 phase cell cycle regulatory proteins". Journal of Molecular Medicine. 77 (4): 386–92. doi:10.1007/s001090050365. PMID 10353443. S2CID 22183443.

- ^ Ohta S, Shiomi Y, Sugimoto K, Obuse C, Tsurimoto T (October 2002). "A proteomics approach to identify proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA)-binding proteins in human cell lysates. Identification of the human CHL12/RFCs2-5 complex as a novel PCNA-binding protein". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (43): 40362–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.M206194200. PMID 12171929.

- ^ Anderson LA, Perkins ND (January 2003). "Regulation of RelA (p65) function by the large subunit of replication factor C". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 23 (2): 721–32. doi:10.1128/mcb.23.2.721-732.2003. PMC 151544. PMID 12509469.

- ^ Ellison V, Stillman B (March 1998). "Reconstitution of recombinant human replication factor C (RFC) and identification of an RFC subcomplex possessing DNA-dependent ATPase activity". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (10): 5979–87. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.10.5979. PMID 9488738.

- ^ Uhlmann F, Cai J, Flores-Rozas H, Dean FB, Finkelstein J, O'Donnell M, Hurwitz J (June 1996). "In vitro reconstitution of human replication factor C from its five subunits". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 93 (13): 6521–6. Bibcode:1996PNAS...93.6521U. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.13.6521. PMC 39056. PMID 8692848.

- ^ Tomida J, Masuda Y, Hiroaki H, Ishikawa T, Song I, Tsurimoto T, et al. (April 2008). "DNA damage-induced ubiquitylation of RFC2 subunit of replication factor C complex". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 283 (14): 9071–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M709835200. PMC 2431014. PMID 18245774.

- ^ a b c Cortese A, Simone R, Sullivan R, Vandrovcova J, Tariq H, Yau WY, et al. (May 2019). "Author Correction: Biallelic expansion of an intronic repeat in RFC1 is a common cause of late-onset ataxia". Nature Genetics. 51 (5): 920. doi:10.1038/s41588-019-0422-y. PMC 6730635. PMID 31028356.

- ^ Scriba CK, Beecroft SJ, Clayton JS, Cortese A, Sullivan R, Yau WY, Dominik N, Rodrigues M, Walker E, Dyer Z, Wu TY, Davis MR, Chandler DC, Weisburd B, Houlden H, Reilly MM, Laing NG, Lamont PJ, Roxburgh RH, Ravenscroft G (October 2020). "A novel RFC1 repeat motif (ACAGG) in two Asia-Pacific CANVAS families". Brain. 143 (10): 2904–10. doi:10.1093/brain/awaa263. PMC 7780484. PMID 33103729.

- ^ Tagliapietra M, Cardellini D, Ferrarini M, Testi S, Ferrari S, Monaco S, Cavallaro T, Fabrizi GM (April 2021). "RFC1 AAGGG repeat expansion masquerading as Chronic Idiopathic Axonal Polyneuropathy". Journal of Neurology. 268 (11): 4280–4290. doi:10.1007/s00415-021-10552-3. PMC 8505379. PMID 33884451.

- ^ Currò R, Salvalaggio A, Tozza S, Gemelli C, Dominik N, Galassi Deforie V, Magrinelli F, Castellani F, Vegezzi E, Businaro P, Callegari I, Pichiecchio A, Cosentino G, Alfonsi E, Marchioni E, Colnaghi S, Gana S, Valente EM, Tassorelli C, Efthymiou S, Facchini S, Carr A, Laura M, Rossor AM, Manji H, Lunn MP, Pegoraro E, Santoro L, Grandis M, Bellone E, Beauchamp NJ, Hadjivassiliou M, Kaski D, Bronstein AM, Houlden H, Reilly MM, Mandich P, Schenone A, Manganelli F, Briani C (June 2021). "RFC1 expansions are a common cause of idiopathic sensory neuropathy". Brain. 144 (5): 2904–10. doi:10.1093/brain/awab072. ISSN 0006-8950. PMC 8262986. PMID 33969391.

- ^ Traschütz A, Cortese A, Reich S, Dominik N, Faber J, Jacobi H, et al. (Group R study) (March 2021). "Natural History, Phenotypic Spectrum, and Discriminative Features of Multisystemic RFC1-disease". Neurology. 96 (9): e1369–e1382. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000011528. PMC 8055326. PMID 33495376.

- ^ Sullivan R, Yau WY, Chelban V, Rossi S, O'Connor E, Wood NW, et al. (April 2020). "RFC1 Intronic Repeat Expansions Absent in Pathologically Confirmed Multiple Systems Atrophy". Movement Disorders. 35 (7): 1277–1279. doi:10.1002/mds.28074. PMID 32333430. S2CID 216129457.

- ^ Cortese A, Tozza S, Yau WY, Rossi S, Beecroft SJ, Jaunmuktane Z, et al. (February 2020). "Cerebellar ataxia, neuropathy, vestibular areflexia syndrome due to RFC1 repeat expansion". Brain. 143 (2): 480–490. doi:10.1093/brain/awz418. PMC 7009469. PMID 32040566.

Further reading

edit- Lu Y, Riegel AT (August 1994). "The human DNA-binding protein, PO-GA, is homologous to the large subunit of mouse replication factor C: regulation by alternate 3' processing of mRNA". Gene. 145 (2): 261–5. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(94)90017-5. PMID 7914507.

- Bunz F, Kobayashi R, Stillman B (December 1993). "cDNAs encoding the large subunit of human replication factor C". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 90 (23): 11014–8. Bibcode:1993PNAS...9011014B. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.23.11014. PMC 47912. PMID 8248204.

- Lu Y, Zeft AS, Riegel AT (June 1993). "Cloning and expression of a novel human DNA binding protein, PO-GA". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 193 (2): 779–86. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1993.1693. PMID 8512577.

- Uhlmann F, Cai J, Flores-Rozas H, Dean FB, Finkelstein J, O'Donnell M, Hurwitz J (June 1996). "In vitro reconstitution of human replication factor C from its five subunits". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 93 (13): 6521–6. Bibcode:1996PNAS...93.6521U. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.13.6521. PMC 39056. PMID 8692848.

- Fotedar R, Mossi R, Fitzgerald P, Rousselle T, Maga G, Brickner H, et al. (August 1996). "A conserved domain of the large subunit of replication factor C binds PCNA and acts like a dominant negative inhibitor of DNA replication in mammalian cells". The EMBO Journal. 15 (16): 4423–33. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00815.x. PMC 452166. PMID 8861969.

- Uchiumi F, Ohta T, Tanuma S (December 1996). "Replication factor C recognizes 5'-phosphate ends of telomeres". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 229 (1): 310–5. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1996.1798. PMID 8954124.

- Mossi R, Jónsson ZO, Allen BL, Hardin SH, Hübscher U (January 1997). "Replication factor C interacts with the C-terminal side of proliferating cell nuclear antigen". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (3): 1769–76. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.3.1769. PMID 8999859.

- Cujec TP, Cho H, Maldonado E, Meyer J, Reinberg D, Peterlin BM (April 1997). "The human immunodeficiency virus transactivator Tat interacts with the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 17 (4): 1817–23. doi:10.1128/mcb.17.4.1817. PMC 232028. PMID 9121429.

- Ubeda M, Habener JF (August 1997). "The large subunit of the DNA replication complex C (DSEB/RF-C140) cleaved and inactivated by caspase-3 (CPP32/YAMA) during Fas-induced apoptosis". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (31): 19562–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.31.19562. PMID 9235961.

- Rhéaume E, Cohen LY, Uhlmann F, Lazure C, Alam A, Hurwitz J, et al. (November 1997). "The large subunit of replication factor C is a substrate for caspase-3 in vitro and is cleaved by a caspase-3-like protease during Fas-mediated apoptosis". The EMBO Journal. 16 (21): 6346–54. doi:10.1093/emboj/16.21.6346. PMC 1170241. PMID 9351817.

- Ellison V, Stillman B (March 1998). "Reconstitution of recombinant human replication factor C (RFC) and identification of an RFC subcomplex possessing DNA-dependent ATPase activity". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (10): 5979–87. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.10.5979. PMID 9488738.

- Coll JM, Hickey RJ, Cronkey EA, Jiang HY, Schnaper L, Lee MY, et al. (1998). "Mapping specific protein-protein interactions within the core component of the breast cell DNA synthesome". Oncology Research. 9 (11–12): 629–39. PMID 9563011.

- Allen BL, Uhlmann F, Gaur LK, Mulder BA, Posey KL, Jones LB, Hardin SH (September 1998). "DNA recognition properties of the N-terminal DNA binding domain within the large subunit of replication factor C". Nucleic Acids Research. 26 (17): 3877–82. doi:10.1093/nar/26.17.3877. PMC 147807. PMID 9705493.

- van der Kuip H, Carius B, Haque SJ, Williams BR, Huber C, Fischer T (April 1999). "The DNA-binding subunit p140 of replication factor C is upregulated in cycling cells and associates with G1 phase cell cycle regulatory proteins". Journal of Molecular Medicine. 77 (4): 386–92. doi:10.1007/s001090050365. PMID 10353443. S2CID 22183443.

- Wang Y, Cortez D, Yazdi P, Neff N, Elledge SJ, Qin J (April 2000). "BASC, a super complex of BRCA1-associated proteins involved in the recognition and repair of aberrant DNA structures". Genes & Development. 14 (8): 927–39. doi:10.1101/gad.14.8.927. PMC 316544. PMID 10783165.

- Yazdi PT, Wang Y, Zhao S, Patel N, Lee EY, Qin J (March 2002). "SMC1 is a downstream effector in the ATM/NBS1 branch of the human S-phase checkpoint". Genes & Development. 16 (5): 571–82. doi:10.1101/gad.970702. PMC 155356. PMID 11877377.

- Anderson LA, Perkins ND (August 2002). "The large subunit of replication factor C interacts with the histone deacetylase, HDAC1". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (33): 29550–4. doi:10.1074/jbc.M200513200. PMID 12045192.

- Ohta S, Shiomi Y, Sugimoto K, Obuse C, Tsurimoto T (October 2002). "A proteomics approach to identify proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA)-binding proteins in human cell lysates. Identification of the human CHL12/RFCs2-5 complex as a novel PCNA-binding protein". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (43): 40362–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.M206194200. PMID 12171929.

- Maruyama T, Farina A, Dey A, Cheong J, Bermudez VP, Tamura T, et al. (September 2002). "A Mammalian bromodomain protein, brd4, interacts with replication factor C and inhibits progression to S phase". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 22 (18): 6509–20. doi:10.1128/MCB.22.18.6509-6520.2002. PMC 135621. PMID 12192049.