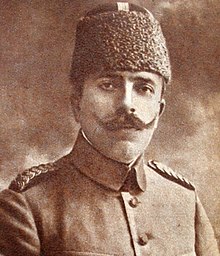

Wehib Pasha also known as Vehip Pasha, Mehmed Wehib Pasha, Mehmet Vehip Pasha (modern Turkish: Kaçı Vehip Paşa or Mehmet Vehip (Kaçı), 1877–1940), was a general in the Ottoman Army. He fought in the Balkan Wars and in several theatres of World War I. In his later years, Vehib Pasha volunteered to serve as a military advisor to the Ethiopian Army against Fascist Italy during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War. He served as the chief of staff to Nasibu Zeamanuel, the Ethiopian Commander-in-Chief on the southern front.[1][2][3][4][5]

Wehib Pasha | |

|---|---|

| |

| Birth name | Mehmed Wehib |

| Born | 1877 Yanya, Janina Vilayet, Ottoman Empire (modern Ioannina, Greece) |

| Died | 1940 (aged 62–63) Istanbul, Turkey |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Rank | General |

| Battles/wars | |

| Relations | Mehmet Emin Efendi (Father), Mehmet Esat Bülkat (Brother), Mehmet Nakyettin Bey (Brother), Kâzim Taşkent (Nephew), Doğan Kardeş (great nephew) |

Biography

editVehib was born in 1877 in Yanya, Janina Vilayet (present day: Ioannina, Greece), then part of the Ottoman Empire. Coming from a prominent family of the city his father, Mehmet Emin Efendi, had served as its mayor.[6] He was an Albanian.[7][8][9] His elder brother Esad Pasha defended Gallipoli in 1915. His younger brother Mehmet Nakyettin Bey was the father of Kâzım Taşkent the founder of Yapı Kredi, the first nationwide private bank in Turkey. Vehib himself graduated from the Imperial School of Military Engineering (Mühendishane-i Berrî-i Hümâyûn) in 1899, then from the Ottoman Military College (Staff College, Mekteb-i Erkân-ı Harbiye-i Şâhâne) as a staff captain and joined the Fourth Army, which was then stationed in Yemen. In 1909, after the 31 March Incident, Vehib was called to Constantinople, where he began to work at the Ministry of War. Shortly afterwards Mahmud Shevket Pasha appointed Vehib as the Commander of the Cadet School (Military high school, Askerî İdadi). He reached the rank of Major.

Balkan wars

editDuring the First Balkan War, Vehib defended the Fortress of Yanya with his brother Esad Pasha who was the commander of the Yanya Corps, until 20 February 1913. The Ottoman forces eventually surrendered to the Greeks under Crown Prince Constantine. After his release as a prisoner of war, Vehib was made a Colonel in the 22nd Infantry Division. He was sent to Hejaz in Arabia.

First World War

editThe Ottoman Empire entered World War I and Vehib participated in the Gallipoli Campaign, commanding the XV Army Corps, and later the Second Army. His successes led to his being made commander of the Third Army during the Caucasus Campaign. His army defended against attacks by the Russians but was defeated in the battle of Erzinjan. In 1918, Vehib's Third Army regained the offensive and took back Trabzon on 24 February, Hopa in March, as well as Batumi on 26 March. With the Armistice of Mudros, Vehib returned to Constantinople.

Armenian Genocide

editVehib Pasha repeatedly condemned the Armenian genocide and gave testimony confirming its existence. He gave evidence to the Mazhar Commission for the Istanbul trials.

"The massacre and destruction of the Armenians and the plunder and pillage of their goods were the results of decision reached by Ittihad's [the Young Turks] Central Committee ... The atrocities were carried out under a program that was determined upon and involved a definite case of premeditation. It was [also] ascertained that these atrocities and crimes were encouraged by the district attorneys whose dereliction of judicial duties in face of their occurrence and especially their remaining indifferent renders them accessories to these crimes."[10][11][12]

"In summary, here are my convictions. The Armenian deportations were carried out in a manner entirely unbecoming to humanity, civilization, and government. The massacre and annihilation of the Armenians, and the looting and plunder of their properties were the result of the decision of the Central Committee of Ittihad and Terakki. The butchers of human beings, who operated in the command zone of the Third Army, were procured and engaged by Dr. Bahaeddin Şakir. The high ranking governmental officials did submit to his directives and order ... He stopped by at all major centers where he orally transmitted his instructions to the party's local bodies and to the governmental authorities."[13]

In 1916, Vehib noticed that a labor battalion of 2,000 Turco-Armenian soldiers had gone missing. He later discovered that the entire battalion had been executed, with the men being tied together in fours and shot. Outraged, he ordered the arrests of Kör Nuri, the gendarmerie commander in charge of the labor battalions, and Çerkez Kadir, the brigand chief who carried out the killings. Vehib had both men court-martialed and hanged for the massacre, and warned his troops not to commit atrocities. Vehib also attempted to have Bahaeddin Şakir and Provincial Governor Ahmed Muammer Bey, who had issued the orders to carry out the massacre, court-martialed. However, Şakir fled and Muammer was transferred out of Vehib's jurisdiction. Şakir was later assassinated by Armenian vigilantes as part of Operation Nemesis.[14][15]

War of Independence

editVehib did not participate in the Turkish War of Independence. After his return to Constantinople at the end of World War I, he was prosecuted for misuse of his office and jailed in Bekirağa prison. He escaped to Italy. His citizenship was revoked by the new government of Turkey. He spent some time in Italy, Germany, Romania, Greece and Egypt. His dislike of Mustafa Kemal was well known and he never hid his contempt for the new leader of Turkey who had once fought under his command at Gallipoli. He did not return to Istanbul until 1940.[16]

Abyssinia

editWhen the Italians invaded Ethiopia in Second Italo-Ethiopian War in the mid-1930s, Vehib volunteered to fight for the Ethiopians. In Ethiopia, he was known as Wehib Pasha, and served as the Chief-of-Staff to Ras Nasibu, the Ethiopian Commander-in-Chief on the southern front. In an interview with The New York Times, he remarked "Out there will be the grave of Italian Fascism. When the Italian native troops hear of ME they will desert."[17] Vehib designed a strong defensive line for the Ethiopians which was known as the "Hindenburg Wall", in reference to the famous German defensive line of World War I, the Hindenburg Line. However, the Italians broke through these defenses during the Battle of the Ogaden in April 1936. After the war was lost, Vehib left Ethiopia and returned to Istanbul.[18]

Death

editHe died in 1940 and was buried at Karacaahmet Cemetery in Istanbul.[19]

See also

editSources

edit- ^ "Eighth Month", Time magazine, 4 May 1936.

- ^ "Empire's End", Time magazine, 11 May 1936.

- ^ "Solemn Hours", Time magazine, 14 October 1935.

- ^ "Water Will Win", Time magazine, 14 October 1935.

- ^ "Newshawks, Seals", Time magazine, 14 October 1935.

- ^ Kayallof, Jacques (1973). The battle of Sardarabad. Mouton. p. 14. ISBN 9783112001394. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ^ Vehib Pasha, the Albanian, was perhaps a tiger; but he was likewise both valiant soldier and grand- seigneur. (Rafael de Nogales, Four Years Beneath the Crescent, C. Scribner's sons, 1926, p. 22.)

- ^ The Ottoman Albanian Vehib Pasha spoke to the Armenians in the language that any romantic nationalist could comprehend, and his point was clearly to cow his opponents with the depth of Ottoman determination. (Michael A. Reynolds, The Ottoman-Russian Struggle for Eastern Anatolia and the Caucasus, 1908-1918: Identity, Ideology and the Geopolitics of World Order, Volume 1, Princeton University, 2003, p. 424.)

- ^ Vehib Pasha said I've been the commander of the Caucasian front for one and a half years. I researched Caucasians and learned. You Caucasians love cleanliness like us Albanians. I won't make these dirty Turkish soldiers to enter into the Caucasus, especially with this guise. (Vehip Paşa «Ben bir buçuk yıldır Kafkas cephesi kumandanıyım. Kafkasyalıları tetkik ettim öğrendim. Siz Kafkasyalılar da, biz Arnavutlar gibi temizliği seviyorsunuz. Bu pis Türk neferlerini, hem de bu kılıkta Kafkasya'ya sokamam.» diyor., Naki Keykurun, Azerbaycan İstiklâl Mücadelesinin Hatıraları, Azerbaycan Gençlik Derneği, 1964, p. 64.)

- ^ Dadrian, Vahakn N. (2004). The history of the Armenian genocide: ethnic conflict from the Balkans to Anatolia to the Caucasus (6th rev. ed.). New York: Berghahn Books. p. 384. ISBN 1-57181-666-6.

- ^ Kiernan 2008, p. 413-14.

- ^ Balakian, Peter (1997). Black dog of fate: a memoir (1 ed.). New York, NY: Basic Books. p. 171. ISBN 0-465-00704-X.

- ^ Forsythe 2009, p. 100.

- ^ Morris, Benny; Ze'evi, Dror (24 April 2019). The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey's Destruction of Its Christian Minorities, 1894–1924. Harvard University Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-674-91645-6.

- ^ Dadrian, Vahakn N. (1994). "The Secret Young-Turk Ittihadist Conference and the Decision for the World War I Genocide of the Armenians". Journal of Political & Military Sociology. 22 (1): 173–201. ISSN 0047-2697. JSTOR 45331941.

- ^ Kevin Jackson, Atlas Tarih, No 03, September 2010, pp. 74-76.

- ^ "The War: Water Will Win". Time. 14 October 1935. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ "WAR: Eighth Month". Time magazine. 4 May 1936. Archived from the original on 1 April 2012.

- ^ "Karacaahmet Cemetery: Notable burials" (PDF). istanbul.edu.tr.

External links

edit- Who is who Archived 28 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine (in Turkish)