The March of Intellect, or the 'March of mind', was the subject of heated debate in early nineteenth-century England, one side welcoming the progress of society towards greater, and more widespread, knowledge and understanding, the other deprecating the modern mania for progress and for new-fangled ideas.

The 'March' debate was seen by Mary Dorothy George as a public reflection of the changes in British society associated with industrialisation, democracy and shifting social statuses – changes welcomed by some and not by others.[1]

Origins and context

editThe roots of the controversy over the March of intellect can be traced back to the spread of education to two new groups in England after 1800 – children and the working-class.[2] 1814 saw the first use of the term the 'march of Mind' as a poem written by Mary Russell Mitford for the Lancastrian Society,[3] and the latter's work in bringing education to children was soon rivalled by the efforts of the Established Church.[4]

The March of Intellect forms part of nineteenth-century debates over science communication, marking a peak in the development of the idea and possession of knowledge. The concept of knowledge as a result of the industrial revolution had changed from the end of the eighteenth century. ‘Polite learning’ practiced by the upper and middle classes through the study of ancient cultures was criticised for being ornamental in its uses by commentators such as Jeremy Bentham.[5] The industrial revolution created a new focus on applied knowledge, particularly regarding natural philosophy (later science) and its various fields. ‘Useful knowledge’ was believed to be the way forward by liberal Whigs, but the definition of this term remained fluid. The increase in periodicals, encyclopaedias and printed literature from the late eighteenth century began to raise questions about the newfound availability of knowledge. Advances in the production of books further extended knowledge to the middle classes and owning printed literature became a desirable commodity. Where a volume would cost around 10 shillings at the beginning of the nineteenth century, by the 1820s a reprint of a volume could be half this value.[6] At the same time, the spread of print culture, artisan coffee houses, and, from 1823 onwards, Mechanics' Institutes,[7] as well as the growth of Literary and Philosophical Societies,[8] meant something of a revolution in adult reading habits.

The working classes had limited access to knowledge owing to poor literacy rates and the expensive cost of printed materials relative to wages. The Spa Fields Riots and Peterloo Massacre raised concerns about revolution and the violent unrest created resistance among the elite towards educating the lower classes.[9] Other conservative commentators supported educating the working class as a means of control. The Edinburgh Review commented in 1813 on the hopes of 'a universal system of education' that would 'encourage foresight and self-respect among the lower orders.' Through education, the working class would know their economic position in life and this would prevent further outbreaks of political unrest.[10] Liberal Whig supporters of educating the working classes, such as Henry Brougham, believed in 'the greatest happiness of the greatest number' outlined by Bentham's utilitarian philosophy.[11] The sciences were seen by these supporters as valuable knowledge for the working classes and debates on the best means of diffusing knowledge was debated.[12]

Peak

editInterest in the so-called March of Intellect came to a peak in the 1820s. On the one hand, the Philosophic Whigs, spearheaded by Brougham, offered a new vision of a society progressing into the future: Thackeray would write of "the three cant terms of the Radical spouters...'the March of Intellect', 'the intelligence of the working classes', and 'the schoolmaster abroad'".[13] Brougham's foundation of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, and of University College, London, seemed to epitomise the new progress of the age.

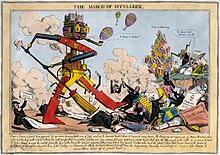

But the same phenomenon of the March of Intellect was equally hailed by conservatives as epitomising everything they rejected about the new age:[14] liberalism, machinery, education, social unrest – all became the focus of a critique under the guise of the 'March'.[15] The March of Intellect was repeatedly satirised in written print and visual media, such as cartoons. Cartoons were frequently used in the nineteenth century to explore current affairs and were becoming increasingly accessible during the peak of the March of Intellect. William Heath’s collection of prints published between 1825 and 1829 have become central representations of the debate.[16] Heath used machines, steam-powered vehicles and other forms of technology in his work to mock liberal Whiggish ambitions that problems in society could be solved through widespread education. The scenes present futuristic visions of society whereby issues such as travel, emigration and postal delivery had been conquered by technological innovation through knowledge.[17] They represent some of the advances in everyday life such as faster travel due to the extension of the railway and the rise in exchanging letters. These and other satirical works from the period recognised that a transformation within society was already in motion, but were ambiguous as to whether reform would be progressive or damaging. For example, Robert Seymour's cartoon entitled 'The March of Intellect' (c.1828) in which a giant automaton sweeps away quacks, delayed parliamentary bills and court cases, can be seen as apocalyptic in its attempt to improve society.[18] The March of Intellect remained ambivalent throughout satire, but recurrently criticised the ambition of educating the working class. In Peacock's 1831 novel Crotchet Castle, one character, Dr. Folliott, satirised the "Steam Intellect Society" and linked the march explicitly to folly, rural protest and the rise in crime: "the march of mind...marched in through my back-parlour shutters, and out again with my silver spoons".[19] Peacock had earlier parodied the Utilitarian take on the role of the modern poet:[20] "The march of his intellect is like that of a crab, backward"[21]

Victorian accommodation

editThe March of Mind was used by the Whigs as one argument for the Great Reform Act; and after a decade of reform and railway, the idea of progress became something of a Victorian truism.[22] Continuing concerns related more to ameliorating its effects than turning back the clock – philosophers fearing over-education would reduce moral and physical fibre,[23] poets seeking to preserve individuality in the face of the utilitarian march.[24]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ M. Dorothy George, Hogarth to Cruikshank (London 1967) p. 177

- ^ G. M. Trevelyan, British History in the Nineteenth Century (London 1922) pp. 163–5

- ^ M. Dorothy George, Hogarth to Cruikshank (London 1967) p. 181n

- ^ G. M. Trevelyan, British History in the Nineteenth Century (London 1922) pp. 163–4

- ^ Burns, James. "From 'Polite Learning' to 'Useful Knowledge' | History Today". www.historytoday.com. Retrieved 2016-11-03.

- ^ "Science Publishing". www.victorianweb.org. Retrieved 2016-11-03.

- ^ G. M. Trevelyan, British History in the Nineteenth Century (London 1922) p. 164

- ^ B. Hilton, A Mad, Bad, & Dangerous People? (Oxford 2008) pp. 171–2

- ^ Rauch, Alan (2001-06-26). Useful Knowledge: The Victorians, Morality, and the March of Intellect. Duke University Press. p. 16. ISBN 0822383152.

- ^ "From 'Polite Learning' to 'Useful Knowledge' | History Today". www.historytoday.com. Retrieved 2016-11-04.

- ^ "History, 1826: Unshackling education- UCL is established". www.ucl.ac.uk. Retrieved 2016-11-04.

- ^ "Science Publishing". www.victorianweb.org. Retrieved 2016-11-04.

- ^ Quoted in M. Dorothy George, Hogarth to Cruikshank (London 1967) p. 177

- ^ Alice Jenkins, Space and the March of Mind (2007) p. 16

- ^ M. Dorothy George, Hogarth to Cruikshank (London 1967) p. 177

- ^ "March of Intellect". The British Library. Retrieved 2016-11-04.

- ^ Schupbach, William (2011). "Flying postmen and magic glass". Wellcome Library. Retrieved 2016-11-04.

- ^ Winter, Alison (1998). Mesmerized: Powers of Mind in Victorian Britain. University of Chicago Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 9780226902234.

- ^ Thomas Love Peacock, Nightmare Abbey and Crotchet Castle (London 1947) pp. 212–3, and pp. 105–6, p. 219

- ^ M. H Abrams, The Mirror and the Lamp (Oxford 1953) p. 126

- ^ Quoted in Ben Wilson, Decency and Disorder (London 2007) p. 317

- ^ B. Hilton, A Mad, Bad, & Dangerous People? (Oxford 2008) p. 611

- ^ E. Gargano, Reading Victorian Schoolrooms (2013) p. 140

- ^ J. Bristow, The Victorian Poet (2014) p. 8

See also Magee, D, 'Popular periodicals, common readers and the "grand march of intellect" in London, 1819-32' (DPhil, Oxon 2008).