Leslie Douglas (Les) Jackson, DFC & Bar (24 February 1917 – 17 February 1980) was an Australian fighter ace of World War II, credited with five aerial victories. Born in Brisbane, he was a businessman when he joined the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Reserve in 1937. Called up for active duty shortly after the outbreak of war in September 1939, he served with No. 23 Squadron in Australia before posting to the South West Pacific theatre with No. 21 Squadron in Singapore. In March 1942 he joined No. 75 Squadron in Port Moresby, New Guinea, flying P-40 Kittyhawks under the command of his eldest brother, John. During the ensuing Battle of Port Moresby, Les shot down four Japanese aircraft.

Leslie Douglas Jackson | |

|---|---|

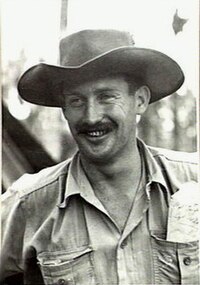

Squadron Leader Jackson commanding No. 75 Squadron in New Guinea, September 1942 | |

| Born | 24 February 1917 Brisbane, Queensland |

| Died | 17 February 1980 (aged 62) Southport, Queensland |

| Allegiance | Australia |

| Service/branch | Royal Australian Air Force |

| Service years | 1937–1946 |

| Rank | Wing Commander |

| Unit |

|

| Commands |

|

| Battles / wars | |

| Awards | Distinguished Flying Cross & Bar |

| Relations | "Old John" Jackson (brother) |

| Other work | Businessman |

Jackson took over command of No. 75 Squadron after his brother was killed in action on 28 April 1942, leading it in the Battle of Milne Bay later that year. Credited with a fifth aerial victory, he became the RAAF's first ace in the New Guinea campaign, and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC). By 1944, Jackson was wing leader of No. 78 (Fighter) Wing in Western New Guinea, gaining promotion to wing commander in September that year. Awarded a bar to his DFC in March 1945, he served as chief flying instructor at No. 8 Operational Training Unit in Australia, and saw out the war as commander of Air Defence Headquarters, Madang. After leaving the RAAF in 1946, Jackson returned to the business world, running two garages. He died in Southport, Queensland, in 1980.

Early career

editLes Jackson was born on 24 February 1917 in the Brisbane suburb of Newmarket, Queensland, the fourth son of businessman William Jackson and his wife Edith. His first job following education at Brisbane Grammar School was as an accountant in the family firm of J. Jackson & Co. Pty Ltd. He then set up his own business running a service station and garage in Surat, a rural area south-west of Brisbane.[1][2] In February 1935, Jackson enlisted in the 2nd/14th Light Horse Regiment, a Queensland-based Militia unit.[3]

Jackson followed his eldest brother, John, into the Royal Australian Air Force Reserve, known as the Citizen Air Force, in July 1937.[4] With the outbreak of World War II, Les was called up for active duty in the RAAF on 6 November 1939.[4][5] He learnt to fly as an air cadet at RAAF Station Point Cook, Victoria. Graduating as a pilot in February 1940, he served initially with No. 23 Squadron at Archerfield, Queensland.[4] In July 1941, he was posted to the South West Pacific theatre with No. 21 Squadron in Singapore.[4] Initially operating CAC Wirraways, the unit converted to Brewster Buffalos in September that year.[6]

Combat service

editPort Moresby

editCompleting his service with No. 21 Squadron in November 1941, Jackson was again posted to No. 23 Squadron in Australia.[2][4] In March 1942, he joined No. 75 Squadron in New Guinea as a flight lieutenant, under the command of his brother, known as "Old John".[7] Operating P-40 Kittyhawks, the unit quickly became engaged in the defence of Port Moresby, one of the crucial early battles in the New Guinea campaign.[8] As one of No. 75 Squadron's flight commanders, Jackson took part in a surprise raid against Lae airfield on 22 March. Five Kittyhawks led by John Jackson attacked and destroyed a dozen Japanese planes on the ground, while four others including Les provided protective cover above; he survived an encounter with three Mitsubishi Zeros that saw two of his fellow pilots shot down. Two days later he recorded his first aerial victory when he intercepted and destroyed a Zero escorting a force of bombers towards Port Moresby.[4][7]

On 6 April, Jackson was forced to ditch his aircraft on a coral reef, but made it to shore with the aid of a life jacket that his brother John dropped to him.[9][10] In the following weeks, Les accounted for another three Japanese aircraft shot down. On 5 April, he was attacked from behind by a Zero while firing on bombers front-on, but was able to turn the tables on the Japanese fighter and shoot it down in flames. The next day he went head to head with more Zeros, damaging two before being forced to ditch on a reef with a smoking engine; once down he scrambled out of the cockpit and danced on the wing to let his comrades know he was safe.[11] Jackson shot down his third victim on 17 April. He achieved his fourth victory against another Zero on 24 April,[12] to become the highest Australian scorer in the Battle of Port Moresby.[11] On 28 April, John Jackson was shot down and killed while leading the interception of a Japanese raid; Les took over command of No. 75 Squadron the next day.[4][12] On 30 April, the squadron was recalled to Australia to refit and regroup; Jackson flew one of its last remaining serviceable aircraft to Cairns, Queensland, on 9 May.[12]

Milne Bay and after

editFollowing re-equipment in Australia, Jackson led No. 75 Squadron back to New Guinea, arriving at Milne Bay on 25 July 1942 in company with another Kittyhawk unit, No. 76 Squadron.[13] During the Battle of Milne Bay, Jackson's squadron was engaged in air defence against Japanese raiders and offensive strikes against convoys and other targets in support of Australian ground forces. On 25 August, the Kittyhawks launched an attack on enemy barges at Goodenough Island that resulted in all seven vessels being set on fire without the loss of any aircraft.[14] The next day, Jackson personally led two of his unit's five concerted strafing assaults on the main Japanese convoy approaching Milne Bay. On 27 August, he and a fellow pilot each claimed a Zero; the Japanese fighters had been focussing on machine-gunning one of their own aircraft that had crash-landed following combat with a USAAF B-26 Marauder, presumably to prevent it falling into Allied hands, and were 'bounced' by the Australian pilots.[4][15] His victory made Jackson an ace, the first from the RAAF in New Guinea.[16] By 28 August, Japanese troops were threatening to overrun the RAAF airfield at Milne Bay, and the Kittyhawk squadrons were ordered to withdraw to Port Moresby for one night. Returning to Milne Bay the next day, Jackson's plane developed trouble and he had to ditch on the coast; with the help of New Guinea natives, he reached Port Moresby by boat three days later.[2][15] By 7 September the Japanese had withdrawn their troops from the Milne Bay area; Generals Sydney Rowell and Cyril Clowes both described the efforts of Nos. 75 and 76 Squadrons as "the decisive factor" in repulsing the invading forces.[17]

No. 75 Squadron was redeployed to Horn Island, Queensland, in September 1942, and Jackson handed over command to Squadron Leader John Meehan the following January.[18][19] In recognition of his "courage and leadership" in New Guinea, Jackson was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC), which was promulgated in the London Gazette on 26 March 1943.[20][21] Having served in staff positions in Australia during the year, he was appointed wing leader of No. 78 (Fighter) Wing, a component of the newly formed No. 10 Operational Group, in December 1943.[1][22] The wing participated in Operations Reckless and Persecution, the assault on Hollandia and Aitape that opened the Western New Guinea campaign, in April 1944.[22] This was followed by the attack on Noemfoor, commencing in June.[23] Jackson was promoted to acting wing commander in September 1944.[1] Completing his tour with No. 78 Wing in December, he was posted to No. 8 Operational Training Unit, New South Wales, as chief flying instructor.[4] In March 1945, Jackson was awarded a bar to his DFC for "determined and successful attacks on enemy installations and shipping". That June, he took command of Air Defence Headquarters in Madang.[1][24]

Post-war career

editJackson continued to lead Air Defence Headquarters in Madang following the end of hostilities, before his commission was terminated in Brisbane on 8 February 1946.[5] Returning to the garage business in rural Queensland, he ran Active Service Motors at Roma and Western Queensland Motors in St George. He married Cynthia Molle at St Andrew's Presbyterian Church, Southport, on 25 January 1947; the couple had three sons. Predeceased by his wife in 1974, Jackson died of a cerebral hemorrhage at Southport on 17 February 1980. He was survived by his children, and cremated in an Anglican ceremony.[1]

Notes

edit- ^ a b c d e Jackson, Leslie Douglas (1917–1980) at Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved on 6 December 2010.

- ^ a b c Newton, Australian Air Aces, p. 93

- ^ Jackson, Leslie Douglas – Australian Military Forces at National Archives of Australia. Retrieved on 10 December 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Garrisson, Australian Fighter Aces, pp. 140–142

- ^ a b Jackson, Leslie Douglas Archived 16 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine at World War 2 Nominal Roll. Retrieved on 10 December 2010.

- ^ Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force 1939–1942, pp. 167–168

- ^ a b Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force 1939–1942, pp. 458–461

- ^ Stephens, The Royal Australian Air Force, pp. 139–141

- ^ Ewer, Storm Over Kokoda, pp. 155–157

- ^ Johnston, Whispering Death, p. 169

- ^ a b Thomas, Tomahawk and Kittyhawk Aces, pp. 51–55

- ^ a b c Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force 1939–1942, pp. 543–548 Archived 22 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force 1939–1942, pp. 603–604

- ^ Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force 1939–1942, pp. 607–609

- ^ a b Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force 1939–1942, pp. 611–613

- ^ Thomas, Tomahawk and Kittyhawk Aces, pp. 58–59

- ^ Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force 1939–1942, pp. 615–617

- ^ Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force 1939–1942, p. 620

- ^ RAAF Historical Section, Units of the Royal Australian Air Force, p. 46

- ^ Recommended: Distinguished Flying Cross at Australian War Memorial. Retrieved on 12 December 2010.

- ^ "No. 35954". The London Gazette (Supplement). 26 March 1943. p. 1414.

- ^ a b Odgers, Air War Against Japan, pp. 206–213

- ^ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, pp.237–241

- ^ "No. 36975". The London Gazette (Supplement). 9 March 1945. p. 1326.

References

edit- Ewer, Peter (2011). Storm Over Kokoda: Australia's Epic Battle for the Skies of New Guinea, 1942. Miller's Point, New South Wales: Murdoch Books. ISBN 978-1-74266-095-0.

- Garrisson, A.D. (1999). Australian Fighter Aces 1914–1953 (PDF). Fairbairn, Australian Capital Territory: Air Power Studies Centre. ISBN 0-642-26540-2. Archived from the original on 26 October 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Gillison, Douglas (1962). Australia in the War of 1939–1945: Series Three (Air) Volume I – Royal Australian Air Force 1939–1942. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 2000369.

- Johnston, Mark (2011). Whispering Death: Australian Airmen in the Pacific War. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74175-901-3.

- Newton, Dennis (1996). Australian Air Aces. Fyshwyck, Australian Capital Territory: Aerospace Publications. ISBN 1-875671-25-0.

- Odgers, George (1968) [1957]. Australia in the War of 1939–1945: Series Three (Air) Volume II – Air War Against Japan 1943–45. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 11218821.

- RAAF Historical Section (1995). Units of the Royal Australian Air Force: A Concise History. Volume 2: Fighter Units. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 0-644-42794-9.

- Stephens, Alan (2006) [2001]. The Royal Australian Air Force: A History. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-555541-4.

- Thomas, Andrew (2005). Tomahawk and Kittyhawk Aces of the RAF and Commonwealth. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84176-083-4.