Kythira (/kɪˈθɪərə, ˈkɪθɪrə/ kih-THEER-ə, KITH-irr-ə; Greek: Κύθηρα [ˈciθira]), also transliterated as Cythera, Kythera and Kithira,[a] is an island in Greece lying opposite the south-eastern tip of the Peloponnese peninsula. It is traditionally listed as one of the seven main Ionian Islands, although it is distant from the main group. Administratively, it belongs to the Islands regional unit, which is part of the Attica region, despite its distance from the Saronic Islands, around which the rest of Attica is centered. As a municipality, it includes the island of Antikythera to the south.

Kythira

Κύθηρα | |

|---|---|

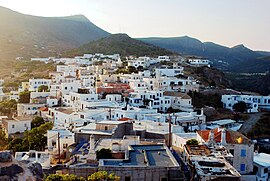

View of Cythera's capital (Chora) from the Castle | |

| Coordinates: 36°15′27″N 22°59′51″E / 36.25750°N 22.99750°E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Administrative region | Attica |

| Regional unit | Islands |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Efstratios Charchalakis[1] (since 2019) |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 300.0 km2 (115.8 sq mi) |

| • Municipal unit | 279.6 km2 (108.0 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 506 m (1,660 ft) |

| Population (2021)[2] | |

| • Municipality | 3,644 |

| • Density | 12/km2 (31/sq mi) |

| • Municipal unit | 3,605 |

| • Municipal unit density | 13/km2 (33/sq mi) |

| • Community | 550 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 801 00 |

| Area code(s) | 2736 |

| Vehicle registration | Z |

| Website | www.kythira.gr |

The island is strategically located between the Greek mainland and Crete, and from ancient times until the mid-19th century was a crossroads of merchants, sailors, and conquerors. As such, it has had a long and varied history and has been influenced by many civilizations and cultures. This is reflected in its architecture (a blend of traditional, Aegean and Venetian elements), as well as the traditions and customs, influenced by centuries of coexistence of the Greek, and Venetian cultures.

Administration

editKythira and the nearby island of Antikythira were separate municipalities until they were merged at the 2011 local government reform; the two islands are now municipal units of Kythira municipality.[3] The municipality has an area of 300.023 km2, the municipal unit 279.593 km2.[4] The province of Kythira (Greek: Επαρχία Κυθήρων) was one of the provinces of Lakonia, then of Argolis and Korinthia, then of Attica Prefecture from 1929 to 1964. Then from 1964 to 1972 Kythira became part of the newly establishment Piraeus Prefecture and after dissolution of Piraeus prefecture returned to Attica Prefecture as part of Piraeus prefecture (Νομαρχία). It was abolished in 2006. From 2011 it is part of the Islands regional unit of Attica region.

History

editPre-classical and ancient

editThere are archaeological remains from the Helladic period, contemporary with the Minoans.[5] There is archaeological evidence of Kythiran trade as far as Egypt and Mesopotamia.

Kythira had a Phoenician colony in the early archaic age; the sea-snail which produces Tyrian purple is native to the island.[citation needed] Xenophon refers to a Phoenician Bay in Kythira (Hellenica 4.8.7, probably Avlemonas Bay on the eastern side of the island). The archaic Greek city of Kythira was at Scandea on Avlemonas; its ruins have been excavated. Its acropolis, now Palicastro (Palaeocastron, "Old Fort"), has the temple of Aphrodite Ourania, who may well represent a Phoenician cult of Astarte.

In classical times, Kythira was part of the territory of several larger city-states. Sparta took the island from Argos early in the sixth century BC, and ruled it under a kytherodíkes (kυθηροδίκης, "judge on Kythira"), in Thucydides' time [4,53,3]; Athens occupied it three times when at war with Sparta (in 456 BC during her first war with Sparta and the Peloponnesians; from 426 to 410 BC, through most of the great Peloponnesian War; and from 393 to 387/386BC, during the Corinthian War against Spartan dominance) and used it both to support her trade and to raid Laconia.

Kythira was independent, and issued her own coins in 195 BC after the Achaean defeat of Sparta. In Augustus' time, it was again subject to Sparta, being the property of Gaius Julius Eurycles, who was both a Spartan magnate and a Roman citizen.

By this time, the Greek cities were in practice subject to the Roman Empire. Kythira continued to exist under the Roman Empire and its Byzantine successor state for centuries. Christianity is attested from the fourth century AD, the time of Constantine; according to her legend, Saint Elessa came from Laconia to convert the island.[6]

Medieval and modern

editcopper engraving by Coronelli.

Kythira is not mentioned in the literary sources for centuries after its conversion; in the period of Byzantine weakness at the end of the seventh century, it might have been exposed to attacks from both the Slavic tribes who raided the mainland and from Arab pirates from the sea. Archaeological evidence suggests the island was abandoned about 700 AD.

When Saint Theodore of Cythera led a resettlement after the Byzantine reconquest of Crete in 962, he found the island occupied only by wandering bands of hunters. He established a great monastery at Paliochora; a town grew up around it, largely populated from Laconia.

When the Byzantine Empire was divided among the conquerors of the Fourth Crusade, the Republic of Venice took her share, three eighths of the whole, as the Greek islands, Kythira among them. She established a coast patrol on Kythira and Antikythera to protect her trade route to Constantinople; Kythira was one of the islands Venice continued to hold despite the Greek reconquest of Constantinople and the Turkish presence all over the Near East.[7] During the Venetian domination the island was known as Cerigo.

Kythirans still talk about the destruction and looting of Paliochora by Barbarossa; it has become an intrinsic part of the Kytherian folklore. One can easily accept the stories of locals by noticing the number of monasteries embedded in the rocky hillsides to avoid destruction by the pirates.

Barbary pirates ranged across the Mediterranean waters, raiding ships, coasts and islands, taking booty and slaves for the Barbary slave trade. Kythira was at the mercy of Barbary pirates due to its strategic location in the Mediterranean. In order to intercept merchant vessels, islands along the trade routes were of course more interesting for pirates.[8] In the 17th century the small islands like Sapientza (Kalamatas) south of Messinia (district in south-western part of the Peloponnese), Cerigo (Kythira) south of the south-eastern tip of the Peloponnese, and along the coast of Asia minor, the then deserted islands of Fourni southwest of Samos, and the island of Psara, west of Chios, were all pirate bases.[9]

When Napoleon put an end to the Venetian Republic in 1797, Kythira was among the islands incorporated in that most distant department of France, called Mer-Égée. Kythira shared a common destiny with the other Ionian islands during the turbulent Napoleonic era, and is still regarded as one of them; it was counted as one of the Cyclades in antiquity.

In 1799, the Ionian islands became the Septinsular Republic, nominally under Ottoman suzerainty, but in practice dominated by Imperial Russia. In 1807, the French recaptured the islands, before they were captured again by the British in 1809, who set up the United States of the Ionian Islands, a British protectorate. The British ruled over the islands for nearly half a century; under British rule, they were governed by a High Commissioner who was granted both legislative and executive powers. During the period of British rule, the city was known as Carigo or Cerigo, a name it had been acquired under Venetian control. After a long period of turbulence in the colony, which even eminent Commissioners as William Ewart Gladstone who served in the role for three weeks in the winter of 1859 failed to resolve, the British discussion whether they were a waste of money or a vital overseas possession ended with the cession of the Ionian Islands, including Kythira, to the new King George I of Greece, who was brother-in-law to the Prince of Wales.

The chief town of the island, Kythira (or Chora, "village"), houses the Historical Archives of Kythira, the second largest in the Ionian islands, after Corfu.

Geography

editKythira has a land area of 279.593 square kilometres (107.95 sq mi); it is located at the southwestern exit from the Aegean Sea, behind Cape Malea.[10] The rugged terrain is a result of prevailing winds from the surrounding seas which have shaped its shores into steep rocky cliffs with deep bays. The island has many beaches, of various composition and size; only half of them can be reached by road through the mountainous terrain of the island. The Kythirian Straits are nearby.

Kythira is close to the Hellenic arc plate boundary zone, and thus highly prone to earthquakes. Many earthquakes in recorded history have had their epicentres near or on the island. Probably the largest in recent times is the 1903 earthquake near at the village of Mitata, that caused significant damage as well as limited loss of life. It has had two major earthquakes in the 21st century: that of November 5, 2004, measuring between 5.6 and 5.8 on the Richter scale and the earthquake of January 8, 2006, measuring 6.9 on the Richter scale. The epicenter of the latter was in the sea about 20 km (12 mi) to the east of Kythira, with a focus at a depth of approximately 70 km (43 mi). Many buildings were damaged, particularly old ones, mostly in the village of Mitata, but with no loss of life. It was felt as far as Italy, Egypt, Malta and Jordan.

Communities and villages

editThe municipal unit Kythira is subdivided into 13 communities (constituent settlements in parentheses):

- Kythira or Chora (Kythira, Kalamos, Kapsali, Manitochori, Pourko, Strapodi)

- Aroniadika (Aroniadika, Pitsinades)

- Karavas (Karavas, Vouno, Gerakari, Kryoneri, Petrouni, Plateia Ammos, Progki)

- Karvounades (Karvounades, Agios Ilias, Alexandrades, Keramoto, Pitsinianika, Stathianika)

- Kontolianika (Kontolianika, Goudianika, Tsikalaria, Fatsadika)

- Livadi (Livadi, Ano Livadi, Katsouni, Lourantianika, Travasarianika)

- Logothetianika (Logothetianika, Kominianika, Lianianika, Perlegkianika)

- Mitata (Mitata, Avlemonas, Agia Moni, Viaradika, Palaiopoli)

- Mylopotamos (Mylopotamos, Araioi, Kato Chora, Piso Pigadi)

- Myrtidia (Drymon, Kalisperianika, Kalokairines, Moni Myrtidion)

- Potamos (Potamos, Agia Anastasia, Agia Pelagia, Kampos)

- Fratsia (Fratsia, Dokana)

- Friligkianika (Friligkianika, Aloizianika, Diakofti, Drymonari, Kampos Palaiopoleos, Kastrisianika)

Climate

editKythira has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification: Csa) with mild, rainy winters and warm to hot dry summers.[11]

| Climate data for Kythira Island | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.5 (70.7) |

22.8 (73.0) |

24.0 (75.2) |

27.0 (80.6) |

33.2 (91.8) |

40.0 (104.0) |

40.2 (104.4) |

37.8 (100.0) |

33.6 (92.5) |

30.0 (86.0) |

26.2 (79.2) |

22.6 (72.7) |

40.2 (104.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 12.7 (54.9) |

12.9 (55.2) |

14.2 (57.6) |

17.1 (62.8) |

21.6 (70.9) |

26.0 (78.8) |

28.7 (83.7) |

28.5 (83.3) |

25.6 (78.1) |

21.2 (70.2) |

17.8 (64.0) |

14.6 (58.3) |

20.1 (68.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.8 (51.4) |

10.8 (51.4) |

12.0 (53.6) |

14.7 (58.5) |

18.8 (65.8) |

23.0 (73.4) |

25.6 (78.1) |

25.4 (77.7) |

22.9 (73.2) |

18.9 (66.0) |

15.8 (60.4) |

12.7 (54.9) |

17.6 (63.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 8.9 (48.0) |

8.9 (48.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

12.4 (54.3) |

16.1 (61.0) |

19.9 (67.8) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.5 (72.5) |

20.3 (68.5) |

16.8 (62.2) |

13.9 (57.0) |

10.8 (51.4) |

15.2 (59.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −1.8 (28.8) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

6.2 (43.2) |

9.4 (48.9) |

11.8 (53.2) |

14.8 (58.6) |

17.2 (63.0) |

11.8 (53.2) |

8.8 (47.8) |

2.0 (35.6) |

1.0 (33.8) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 103.3 (4.07) |

67.7 (2.67) |

59.5 (2.34) |

28.1 (1.11) |

10.5 (0.41) |

1.9 (0.07) |

2.4 (0.09) |

2.3 (0.09) |

11.2 (0.44) |

54.2 (2.13) |

85.6 (3.37) |

115.2 (4.54) |

541.9 (21.33) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 10.2 | 8.5 | 6.4 | 4.0 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 5.1 | 7.7 | 11.0 | 56.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 72.3 | 72.4 | 71.5 | 67.9 | 63.1 | 57.1 | 54.4 | 56.7 | 62.1 | 68.3 | 72.5 | 72.8 | 65.9 |

| Source: NOAA[12] | |||||||||||||

Mythology

editIn Ancient Greek mythology, Kythira was considered to be the island of celestial Aphrodite, the Goddess of love (cf. Cyprus, another island devoted to the Goddess of Love). She is said to have been birthed from sea foam near the island.[13]

Demographics

editLike many of the smaller Aegean islands, Kythira's population is decreasing. While the island had reached a peak population of about 14,500 in 1864, that has steadily declined mostly due to emigration, both internal (to major urban centres of Greece) and external (to Australia, the United States, Germany) in the first half of the 20th century. Today its population hovers around 3,650 people (2021 census).

Economy

editSince the late 20th century, the Kythirean economy has largely focused and, in the process, has become dependent on tourism, which provides the majority of the island's income, despite the fact that Kythira is not one of the most popular tourist destinations in Greece. The popular season usually begins with the Greek holiday of Pentecost at the end of May, and lasts until the middle of September. During this time, primarily during August, the island's population will often triple due to the tourists and natives returning for vacation. Dependence on tourism has resulted in increased building activity in many of the island's villages, mostly for commercial purposes (hotels and hospitality facilities, shops etc.), but also secondary homes; prominent examples are Agia Pelagia and Livadi, both of which having witnessed significant growth in their size since the early 1990s.

Minor sources of revenue are thyme honey, famous within Greece for its rich flavor, as well as some small-scale cultivation of vegetables and fruit and animal husbandry that is, nevertheless, increasingly restricted to local consumption.

Only five of the island's villages are on the coast (Platia Amos, Agia Pelagia, Diakofti, Avlemonas, & Kapsali). During July and August, several traditional dances will be held in various villages. These dances usually attract the majority of the island's population, the biggest of which are the festival of 'Panagia' in Potamos on 15 August, and the wine festival in Mitata on the first Friday and Saturday of August.

Infrastructure

editThe Trifylleion Hospital of Kythera is the only hospital on the island. The hospital's construction was made possible through the contributions of Greek Americans, including Mixalis Semitekolos, also known as Mike Semet, who was a prominent figure in the New York City restaurant industry in the early 20th century. Semitekolos, an immigrant from Kythera, raised funds for the hospital by participating in a pan-Kytherian fundraising campaign in the United States in the early 1950s. His significant monetary contributions earned him recognition from King Paul of Greece with the Order of the Phoenix. The groundbreaking for the hospital was on May 21, 1953, in Potamos, making it the first hospital on the island. It remains the only hospital on the island to this day, providing essential medical services to the residents of Kythira and the surrounding areas. The charitable organization responsible for the hospital evolved to become the Trifylleion Foundation of Kytherians and is still active today.[14][15]

Kythira (town)

editThe capital, Chora, is located on the southern part of the island having no ports connected to the southern Peloponnese or Vatika. Kythira's port for Vatika was previously situated at Agia Pelagia, although in recent years this port has been decommissioned and has been replaced by a new port at the coastal town of Diakofti, Kythira.

Most of the over 60 village names end with "-anika" and a few end with -athika, -iana and -wades. This is due to the villages being named after influential families that settled first in that region. For Example, 'Logothetianika' is derived from the Greek last name of 'Logothetis'.

Officially, Greek is Kythira's main language. Despite popular belief, most places such as public services and local administrations, will be able to oblige to an individual's needs in English as well. In specific areas, some of Kythira's population is fluent in Italian.[16]

Transportation

editThe island in the past has been plagued by a poor infrastructure, exacerbated by the effect of weather on transportation during the winter months.[citation needed] However the construction of the new port in Diakofti along with the renovation of the island's airport have significantly reduced these effects. A new road from the island's most populated town of Potamos in the north to the island's capital of Chora in the south is currently in the planning and development stage.

Port

editDespite the fact that the island has been a trade route for centuries, construction of a modern port was postponed several times until the latter half of the 20th century. In 1933, efforts were made to construct a port in the village of Agia Pelagia, yet financial and governmental problems meant that it was only decades later that one was built. That small port of Agia Pelagia (currently being renovated from a ferry dock to a tourist/recreational boat dock) was the island's main port until the mid-1990s. Around that time the new port of Diakofti, the site originally chosen by the British colonial administration in the 19th century, was constructed along with a modern wider road, aiming to support larger cargo and passenger vessels. The port of Diakofti currently serves scheduled routes to/from Gythion, Kalamata, Antikythera, Piraeus' Athens port, Crete & Neapolis - Vatika. Proposals have been made to attach a marina to the south side of the port, however no plans or timetables have been produced. Additionally, the harbour of Agia Patrikia (north of Agia Pelagia) is the primary fishing boat harbour, housing two wide boatramps and a boat repair facility.

Airport

editThe island's primary airport is the Alexander S. Onassis Airport also known as Kithira Island National Airport, located in the region between the village of Friligiannika and Diakofti, about 20 km (12 mi) from the capital. The airport was revamped and extended at the turn of the 21st century, largely by private funds provided by the local population. The island is served by Olympic Air and Aegean Airlines flights.

Notable people

edit- Henry Ernest Gascoyne Bulwer, British colonial administrator and diplomat

- Athanassio Comino, oyster merchant and businessman

- Juliette de Baïracli Levy (1912–2009), herbalist and author

- George B. Dertilis, historian

- Alex Freeleagus, Australian lawyer and former Consul-General to Greece in Queensland

- Lafcadio Hearn, writer and translator

- Tess Mallos, Australian food and cooking writer

- Mitchell Notaras, Australian surgeon and philanthropist.

- John Panaretos, educator and statistician

- Zoë Paul, sculptor and painter

- Philoxenus (435-380 BC), dithyrambic poet

- Nick Politis, Australian businessman

- Serapheim Savvaitis, Igumen

- John Stathatos, photographer and writer

- Spyridon Stais, politician

- Valerios Stais (1857–1923), archaeologist

- Peter V'landys, Australian horse racing and rugby league administrator

- Gian Berto Vanni, Italian painter

- Marco Venier, Lord of Cerigo (– 1311) was a Lord of Cerigo

- Yianis Vilaras (1771–1823), poet and author

In popular culture

edit- Mentioned in Horace's Odes 3.12

- Named as a destination of the galley carrying Judah Ben-Hur in Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ by Lew Wallace.

- Botticelli's The Birth of Venus and other similarly themed paintings show the goddess Venus arriving either at the shore of Kythira or Cyprus, as classical mythology identifies both islands as her birthplace.

- In the 1499 text Hypnerotomachia Polifili the protagonists Polia and Polifilo travel to Cythera to explore their love and find the fountain of Venus.

- The island's status as the birthplace of the goddess is also referenced in the title and subject of the Antoine Watteau painting Embarkation for Cythera.

- François Couperin wrote Le Carillon de Cythere for harpsichord.

- Watteau represents the island in his painting Embarquement pour Cythère

- Charles Baudelaire, in the poem A Voyage to Cythera, called the island a "banal Eldorado".

- The Baudelaire poem is quoted and the island is referenced in Anthony Powell's The Kindly Ones (1962), part of A Dance to the Music of Time.

- A stanza from the Baudelaire poem is quoted as an allusion to Haiti by young Philippot in Graham Greene's The Comedians.

- A Voyage to Cythera is the title of a short story (1967) by Margaret Drabble.

- Taxidi sta Kythira (Voyage to Cythera) is the title of a movie (1984) directed by Theo Angelopoulos.

- The song "In Cythera" was released by alternative rock group Killing Joke on their 2012 album MMXII.

- Cythera is mentioned in the song "J'ai volé le lit de la mer" by French pop singer-songwriter Nolwenn Leroy, released on her 2012 ocean and mermaid-themed album Ô Filles de l'eau ("Vers Cythère j'ai vogué").[17][18]

- Adventures on Kythera is an Australian children's TV show set here.

Gallery

edit-

View on Kapsali

-

Church of Agios Georgios

-

View of the Kytherian Straits

-

West coast

-

Avlemonas at southeastern coast

-

Paleopoli Beach

-

Monastery of Panagia Myrtidiotissa

-

Gold Icon of Panagia Myrtidiotissa

-

Church of Agia Despoina

-

The castle of Kythira by night

-

Winery in Martesakia (Pitsinianika) showing neoclassical architecture

-

Cave in islet Hytra

-

Kythira's main port, Diakofti

-

The shipwreck

-

Melidoni beach

-

Kaladi beach

-

Hytra view from the castle

-

Lion from the Kythira Archaeological museum.

-

Dry landscape in Kythera.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ The Italian name Cerigo can be used in speaking of late medieval and early modern Kythira.

References

edit- ^ Municipality of Kythira, Municipal elections – October 2023, Ministry of Interior

- ^ "Αποτελέσματα Απογραφής Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2021, Μόνιμος Πληθυσμός κατά οικισμό" [Results of the 2021 Population - Housing Census, Permanent population by settlement] (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority. 29 March 2024.

- ^ "ΦΕΚ A 87/2010, Kallikratis reform law text" (in Greek). Government Gazette.

- ^ "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-21.

- ^ Georgiadis, Mercourios (1 January 2023). The Sacred Landscape at Leska and Minoan Kythera. INSTAP Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-62303-442-9.

- ^ Brill's New Pauly, article on "Cythera" (for entire section), citing Paus. 1,27,5; Thuc. 4,53,1ff.; 57,4; 5,14,3; 18,7; 7,26,2; 57,6; Xen. Hell. 4,8,7; Isoc. Or. 4,119, and Cassius Dio 54,7,2).

- ^ Fernand Braudel, The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean world in the age of Philip II, trans. Reynolds. In the 1995 ed. Vol II, p.877.

- ^ Simbula, P F. Iles. p. 3.

- ^ Zakythinos, D A. Corsaires et pirates. pp. 713–714.

- ^ C.Michael Hogan. 2011. Aegean Sea. Eds. P.Saundry & C.J.Cleveland. Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the Environment. Washington DC

- ^ Kottek, M.; J. Grieser; C. Beck; B. Rudolf; F. Rubel (2006). "World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated" (PDF). Meteorol. Z. 15 (3): 259–263. Bibcode:2006MetZe..15..259K. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130. Retrieved January 22, 2013.

- ^ "Kythira Island Climate Normals 1961-1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 22, 2013.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony l. 192

- ^ "» 101 West 66th Street, The Colonial". Retrieved 2023-04-02.

- ^ "Mixalis-Semitekolos| Kytherian Society of California | KSOCA". www.ksoca.com. Retrieved 2023-04-02.

- ^ "Useful information about Kyhera". Visit Kythera. Archived from the original on 11 October 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ "Nolwenn Leroy - J'ai volé le lit de la mer Lyrics | Lyrics.com". www.lyrics.com. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ^ Sicking, Louis. "Islands, Pirates, Privateers and the Ottoman Empire in the Early Modern Mediterranean". Seapower, Technology and Trade: Studies in Turkish Maritime History. Proceedings Eurasian Maritime History Conference, Istanbul, 5–9 November 2012 (Istanbul 2014).

External links

edit- Visit Kythera Travel Guide

- Kythera (in Greek, English, and Italian) Travel Guide

- The Kythera Island Project Archived 2009-09-25 at the Wayback Machine—an archaeological, ecological, and historic research project of the island and its peoples.

- Kythera-Family.net—A cultural archive for the island of Kythira, with over 15,000 heritage entries from people of Kytherian descent from all over the world.

- Kythira island Travel Guide