Yibna (Arabic: يبنا; Jabneh or Jabneel in Biblical times; Jamnia in Roman times; Ibelin to the Crusaders), or Tel Yavne, is an archaeological site and depopulated Palestinian town. The ruins are located southeast of the modern Israeli city of Yavne.

Yibna

يبنا Tel Yavne | |

|---|---|

Mamluk minaret in Yibna | |

| Etymology: Built[1] | |

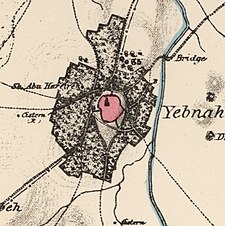

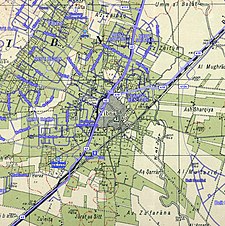

A series of historical maps of the area around Yibna (click the buttons) | |

Location within Mandatory Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 31°51′58″N 34°44′47″E / 31.86611°N 34.74639°E | |

| Palestine grid | 126/141 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Ramle |

| Date of depopulation | 4 June 1948[3] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 59,554 dunams (59.554 km2 or 22.994 sq mi) |

| Population (1945) | |

| • Total | 5,420[2] |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Military assault by Yishuv forces |

| Secondary cause | Expulsion by Yishuv forces |

| Current Localities | Yavne,[4] Beit Raban, Kfar HaNagid, Beit Gamliel |

The town had a population of 5,420 in 1948, located 15 kilometers southwest of Ramla.[5] Most of the population fled after the fall of al-Qubeiba and Zarnuqa in late May, but armed males were forced back. Israeli forces took the town on June 5 and expelled the remaining population.[6]

It is a significant site for post-biblical Jewish history, as it was the location of the Council of Jamnia, considered the birthplace of modern Rabbinic Judaism. It is also significant in the history of the Crusades, as the location of the House of Ibelin.

Name

editIn many English translations of the Bible, it is known as Yavne or Jabneh /ˈdʒæbnə/. In classical antiquity, it was known as Jamnia (Koinē Greek: Ἰαμνία, romanized: Iamníā; Latin: Iamnia); to the Crusaders as Ibelin; and before 1948, as Yibna. (Arabic: يبنا)

History

editBased on written sources and archaeology, the history of Yavneh/Jabneh/Yibna goes back to the Iron Age and possibly to the Bronze Age. The Hebrew Bible mentions Yavneh repeatedly, as does Josephus. For more see Yavne.

Bronze and Iron Age

editSalvage excavations carried out in 2001 by the Israel Antiquities Authority uncovered several burials at the northern foot of the original tell. Most of the burials are dated to the later Iron Age. One burial points to a late Bronze Age occupation.

A large Philistine favissa (deposit of cultic artifacts) was discovered on Temple Hill.[8] Two excavation seasons in the 2000s led by Professor Dan Bahat revealed some Iron Age remains.[citation needed] Pottery sherds of the Iron Age and Persian period were discovered at the surface of the tell.[9]

Roman period with Herodians

editIn Roman times, the city was known as Iamnia, also spelled Jamnia. It was bequeathed by Herod the Great upon his death to his sister Salome I. Upon her death, it passed to the Roman emperor Augustus, who managed it as a private imperial estate, a status it was to maintain for at least a century.[10] After Salome's death, Iamnia came into the property of Livia, the future Roman empress, and then to her son Tiberius.[11]

During the First Jewish–Roman War, when the Roman army had quelled the insurrection in Galilee, the army then marched upon Iamnia and Azotus, taking both towns and stationing garrisons within them.[12] According to rabbinic tradition, the tanna Yohanan ben Zakkai and his disciples were permitted to settle in Iamnia during the outbreak of the war, after Zakkai, realizing that Jerusalem was about to fall, sneaked out of the city and asked Vespasian, the commander of the besieging Roman forces, for the right to settle in Yavne and teach his disciples.[13][14] Upon the fall of Jerusalem, his school functioned as a re-establishment of the Sanhedrin.[15]

Byzantine period

editByzantine period finds from excavations include an aqueduct east of the tell, and a kiln.[16][17] The world's largest wine factory from the Byzantine period has been uncovered by Israeli archaeologists, after a two-year excavation process; the importance of its wine was exemplified by its use by emperor Justin II in 566 at his table during his coronation feast.[18]

Early Islamic period

editThe historian al-Baladhuri (d. 892 CE) mentioned Yibna as one of ten towns in Jund Filastin conquered by the Rashidun army led by Amr ibn al-As during the Muslim conquest of the Levant.[19] The 9th-century historian Ya'qubi wrote that it was an ancient city built on a hill and inhabited by Samaritans.[19]

The geographer al-Maqdisi, writing around 985, said that "Yubna has a beautiful mosque. From this place come the excellent figs known by the name of Damascene."[19] The geographer Yaqut al-Hamawi wrote that in Yubna there was a tomb said to be that of Abu Hurayra, a Companion of the Prophet. The author of the Marasid also adds that tomb seen here is also said to be that of Abd Allah ibn Sa'd, another Companion of the Prophet.[19]

In 2007, remains ranging from the early Islamic period until the British Mandate period were uncovered.[20] An additional kiln, and part of a commercial/industrial area were uncovered at the west of the tell in 2009.[21]

Crusader, Ayyubid and Mamluk periods

editThe Crusaders called the city Ibelin and built a castle there in 1141. Two excavation seasons led by Professor Dan Bahat starting in 2005 revealed the main gate.[citation needed] Its namesake noble family, the house of Ibelin, was important in the Kingdom of Jerusalem and later in the Kingdom of Cyprus. Salvage excavations at the west of the tell unearthed a stash of 53 Crusader coins of the 12th and 13th centuries.[21]

Ibelin was first sacked by Saladin before his army was comprehensively routed at the Battle of Montgisard in late 1177. In August 1187, it was retaken by Saladin and burned down, and ceased for some time to form part of the Crusaders' kingdom.[22] The Jewish traveler Benjamin of Tudela (1130–1173) identified Jamnia (Jabneh) of classical writers with the Ibelin of the Crusades. He places the ancient city of Jamnia at three parasangs from Jaffa and two from Ashdod (Azotus).[23]

During the Mamluk period (13th–16th centuries), Yibna was a key site along the Cairo—Damascus road, which served as a center for rural religious and economic life.[24] Ibelin's parish church was converted into a mosque, to which a minaret was added during the Mamluk period in 1337. The minaret survives until today, while the mosque (the former Crusader church) was blown up by the Israeli army in 1950.[7][25]

The Mausoleum of Abu Huraira, a maqam (religious shrine), in Yibna was described as "one of the finest domed mausoleums in Palestine". The site has been considered by Muslims as the tomb of Abu Huraira since the 12th century. After Israel's capture of Yibna in 1948, the shrine was taken over by Sephardic Jews who consider the tomb as the burial place of Rabbi Gamaliel of Yavne.[26]

Ottoman period

editThe village became part of the Ottoman Empire in 1517. In the 1596 Ottoman tax registers, it fell under the nahiya (subdistrict) of Gaza, part of the liwa' (district) of Gaza, with a population of 129 households, an estimated 710 persons, all Muslims. The villagers paid a fixed tax rate of 25% on a number of crops, including wheat, barley, summer crops, sesame seeds and fruits, as well as goats, beehives and vineyards; a total of 34,000 akçe. Three quarters of the revenues went to a waqf (religious endowment).[27]

In the French campaign in Egypt and Syria in 1799, it was shown on the map that Pierre Jacotin compiled that year as 'Ebneh'.[28]

An American missionary, William Thomson, who visited Yibna in 1834, described it as a village on hill inhabited by 3,000 Muslims who worked in agriculture. He wrote that an inscription on the mosque indicated that it had been built in 1386, while Denys Pringle indicates 1337 as the construction year of the minaret.[7][29][30] In 1838, Yibna was noted as a Muslim village in the Gaza district.[31]

An Ottoman village list from 1870 found that Yibna had a population of 1,042 living in 348 houses, although this number only counted adult males.[32][33] In 1882, the Palestine Exploration Fund's Survey of Western Palestine described Yibna as a large village partly built of stone and situated on a hill. It had olive trees and corn to the north, and gardens nearby.[34]

British Mandate

editIn 1921, an elementary school for boys was founded in Yibna. By 1941-42 it had 445 students. A school for girls was founded in 1943, and by 1948 it had 44 students.[5]

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Yibna had a population of 1,791; all Muslims,[35] increasing in the 1931 census to 3,600, of whom all were Muslims except for seven Christians, two Jews and one Baháʼí, living in a total of 794 houses.[36]

In 1941, Kibbutz Yavne was established nearby by refugees from Germany, followed by a Youth Aliyah village, Givat Washington, in 1946.[5]

In 1944-45, Yibna had a population of 5,400 Muslims and 20 Christians,[2] while the total land area was 59,554 dunams, according to an official land and population survey.[37] In addition there were 1,500 nomads living around the village.[5] A total of 6,468 dunams of village land was used for citrus and bananas, 15,124 were used for cereals, 11,091 were irrigated or used for orchards, of which 25 were planted with olive trees,[5][38] while 127 dunams were classified as built-up areas.[39]

-

Yibna 1929 1:20,000

-

Yibna 1941 1:20,000

-

Yibna 1945 1:250,000

1948 and aftermath

editYibna was in the territory allotted to the Jewish state under the 1947 UN Partition Plan.[40] In mid-March 1948, a contingent of Iraqi volunteers moved into the village. In a Haganah reprisal on March 30, two dozen villagers were killed.[41] On April 21, the Iraqi village commander was arrested by the British authorities for the drunken shooting of two Arabs.[41]

During the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, residents of Zarnuqa sought refuge in Yibna, but left after Yibna's inhabitants accused them of being traitors.[42] On 27 May, following the fall of nearby al-Qubayba and Zarnuqa, most of the population of Yibna fled to Isdud, but Yibna's armed males were forced back to Yibna by Isdud's militiamen. According to the official history, the Israeli Givati Brigade was interested in evacuating the village.[42] On June 5, after a brief firefight, they took the village and found it deserted apart from a few old people who were expelled.[42] Refugees fleeing the village were fired at 'to increase [their] panic.'[42]

After 1948, a number of Israeli villages were founded on Yibna's land: Kfar HaNagid and Beit Gamliel in 1949, Ben Zakai in 1950, Kfar Aviv (originally: "Kfar HaYeor") in 1951, and Tzofiyya in 1955.[43]

Archaeological excavations have revealed that part of the pre-1948 Arab village at Yibna was built on top of a Byzantine-period cemetery and refuse pits.[44]

Cultural references

editPalestinian artist Sliman Mansour made Yibna the subject of one of his paintings. The work, named for the village, was one of a series of four on destroyed Palestinian villages that he produced in 1988 in order to resist the cancellation of Palestinian history; the others being Yalo, Imwas and Bayt Dajan.[45]

The harbour of Javneh

editThe harbour of ancient Yavneh has been identified on the coast at Minet Rubin (Arabic) or Yavne-Yam (Hebrew), where excavations have revealed fortification going back to the Bronze Age Hyksos.[9] It has been in use from the Middle Bronze Age until the 12th century CE, when it was abandoned.[46]

Notable residents/descendants

editSee also

editReferences

edit- ^ Conder, C. R. (Claude Reignier); Palestine Exploration Fund; Kitchener, Horatio Herbert Kitchener; Palmer, Edward Henry (1881). The survey of Western Palestine : Arabic and English name lists collected during the survey. Robarts - University of Toronto. London : Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- ^ a b Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 30

- ^ Morris, Research Fellow Truman Institute Benny; Morris, Benny; Benny, Morris (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- ^ Morris, Research Fellow Truman Institute Benny; Morris, Benny; Benny, Morris (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- ^ a b c d e Khalidi, 1992, p.421

- ^ Morris, Research Fellow Truman Institute Benny; Morris, Benny; Benny, Morris (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- ^ a b c Pringle, Denys (1993). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: A Corpus: Volume 2, L-Z (excluding Tyre). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-39037-8.

- ^ Kletter, Raz; Ziffer, Irit; Zwickel, Wolfgang (2010). Yavneh. Saint-Paul. ISBN 978-3-7278-1667-3.

- ^ a b Negev, and Gibson, 2001, p. 253

- ^ Kletter, Raz (2004). "Tel Yavne". Excavations and Surveys in Israel. 116. Retrieved 2017-12-31.

- ^ "Jabneh". Jewish Virtual Library.

- ^ "Flavius Josephus, The Wars of the Jews, Book IV, Whiston chapter 3, Whiston section 2". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2022-12-31.

- ^ Nathan ha-Bavli (1976). Shemuel Yerushalmi (ed.). Avot de-Rabbi Natan (in Hebrew). Jerusalem: Mekhon Masoret. p. 29 (chapter 4, section 5). OCLC 232936057.

- ^ Ben-Israel, Uriah (1979). "Yavne". In Alon, David (ed.). Israel Guide - Sharon, Southern Coastal Plain and Northern Negev (A useful encyclopedia for the knowledge of the country) (in Hebrew). Vol. 6. Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House. p. 132. OCLC 745203905.

- ^ "Babylonian Talmud: Gittin 56". www.come-and-hear.com. Retrieved 2022-12-31.

- ^ Velednizki, Noy (2004). "Yavne Final Report". Excavations and Surveys in Israel. 116. Archived from the original on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- ^ Sion, Ofer (2005). "Yavne Final Report". Excavations and Surveys in Israel. 117. Retrieved 2017-12-31.

- ^ Jeevan Ravindran (12 October 2021). "World's largest Byzantine wine factory uncovered in Israel". CNN. Retrieved 2022-12-31.

- ^ a b c d Le Strange, G. (Guy) (1890). Palestine under the Moslems; a description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Translated from the works of the mediaeval Arab geographers. Robarts - University of Toronto. London A.P. Watt.

- ^ "Volume 121 Year 2009 Tel Yavne". www.hadashot-esi.org.il. Retrieved 2022-12-31.

- ^ a b Shimron, Ilanit (2009-04-06). מטמון נדיר נמצא בחפירות ארכיאולוגיות בתל יבנה [Rare Treasure Found in Excavations at Tel Yavne] (in Hebrew). Ynet.co.il (local). Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- ^ Fischer, Moshe and Taxel, Itamar. "Ancient Yavneh: Its History and Archaeology", in Tel Aviv Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University, December 2007, vol. 34: No 2, pp.204-284, 247

- ^ "JABNEH - JewishEncyclopedia.com". www.jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2022-12-31.

- ^ Marom, Roy; Taxel, Itamar (2023-10-01). "Ḥamāma: The historical geography of settlement continuity and change in Majdal 'Asqalan's hinterland, 1270–1750 CE". Journal of Historical Geography. 82: 49–65. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2023.08.003. ISSN 0305-7488.

- ^ [Raz Kletter, Irit Ziffer, Wolfgang Zwickel. "Yavneh I: The Excavation of the 'Temple Hill' Repository Pit and the Cult Stands." Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis, Series Archaeologica (OBOSA), Book 30. Academic Press Fribourg, Switzerland (ISBN 978-3-7278-1667-3) and Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen (ISBN 978-3-525-54361-0). 2010. Pages 2-13 ]

- ^ Petersen, Andrew. "Gazetteer 6. S-Z".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 143. Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 421

- ^ Karmon, 1960, p. 171 Archived 2017-12-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Thompson (1880), I:145-49. Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p.421

- ^ Thomson, William M. (1861). The land and the book ; or, biblical illustrations drawn from the manners and customs, the scenes and scenery of the Holy Land. Oxford University. London : T. Nelson.

- ^ Robinson, Edward; Smith, Eli (1841). Biblical researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea : a journal of travels in the year 1838. Robarts - University of Toronto. Boston : Crocker.

- ^ Deutscher Verein zur Erforschung Palästinas (1878). Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. Getty Research Institute. Leipzig, O. Harrassowitz [etc.]

- ^ Deutscher Verein zur Erforschung Palästinas; Deutsches Evangelisches Institut für Altertumswissenschaft des Heiligen Landes (1878). Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. University of California. Leipzig : K. Baedeker.

- ^ Conder, C. R. (Claude Reignier); Kitchener, Horatio Herbert Kitchener; Palmer, Edward Henry; Besant, Walter (1881–1883). The survey of western Palestine : memoirs of the topography, orography, hydrography, and archaeology. Robarts - University of Toronto. London : Committee of the Palestine exploration fund.

- ^ "Palestine Census ( 1922)" – via Internet Archive.

- ^ E. Mills (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of villages, towns and administrative areas.

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 68

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 117

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 167

- ^ "Map of UN Partition Plan". United Nations. Archived from the original on January 24, 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- ^ a b Morris, Research Fellow Truman Institute Benny; Morris, Benny; Benny, Morris (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- ^ a b c d Morris, Research Fellow Truman Institute Benny; Morris, Benny; Benny, Morris (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- ^ Khalidi, 1992, p. 423

- ^ Buchennino, 2007, Yavne Archived 2011-07-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ankori, 2006, p. 82: 'Another series of four works from 1988 relates explicitly to the lost homeland through the titles given to each work by the artist. Mansour named each composition (Yalo, Beit Dajan, Emmwas, Yibna) after a Palestinian village that had been destroyed by Israel since its establishment in 1948. Thus, art became a way of resisting the eradication of Palestinian history and geography,’.

- ^ "Archeology in Israel - Yavne Yam". www.jewishmag.com. Retrieved 2022-12-31.

Bibliography

edit- Ankori, Gannit (2006). Palestinian Art. Reaktion Books. ISBN 1-86189-259-4 – via Internet Archive.

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine – via Internet Archive.

- Buchennino, Aviva (2006-01-08). "Yavne". Hadashot Arkheologiyot. Israeli Antiquities Authority. ISSN 1565-5334. Archived from the original on 2011-07-19.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H. H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund – via Internet Archive.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Fischer, Moshe; Taxel, Itamar (2007). "Ancient Yavneh, Its history and archaeology". Tel Aviv. 34 (2): 204–284. doi:10.1179/tav.2007.2007.2.204. S2CID 161092698.

- Fischer, Moshe; Taxel, Itamar; Amit, David (2008). "Rural Settlement in the Vicinity of Yavneh in the Byzantine Period: A Religio-Archaeological Perspective". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 350 (350): 7–35. doi:10.1086/BASOR25609264. JSTOR 25609264. S2CID 163487105.

- Guérin, V. (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 1: Judee, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale – via Internet Archive. (p. 55 ff )

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Remembered (Report). Palestine Liberation Organization Research Centre.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149 – via Internet Archive.

- Hütteroth, W.-D.; Abdulfattah, K. (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Karmon, Y. (1960). "An Analysis of Jacotin's Map of Palestine" (PDF). Israel Exploration Journal. 10 (3, 4): 155–173, 244–253. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-12-01.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Kletter, Raz (2004-05-31). "el Yavne Final Report". Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel (116). ISSN 1565-5334.

- Le Strange, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund – via Internet Archive.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine – via Internet Archive.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Negev, Avraham; Gibson, S. (2001). "Jabneh; Jabneel; Jamnia (a)". Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land. New York and London: Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-1316-1.

- Palmer, E. H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund – via Internet Archive.

- Petersen, Andrew (2001). A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology). Vol. I. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-727011-0.

- Pringle, D. (1997). Secular buildings in the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: an archaeological Gazetteer. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-46010-7. p. 108

- Pringle, D. (1998). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: L-Z (excluding Tyre). Vol. II. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39037-0.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster – via Internet Archive.

- Sion, Ofer (2005-08-07). "el Yavne Final Report". Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel (117). ISSN 1565-5334.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163 – via Internet Archive.

- Thomson, W.M. (1859). The Land and the Book: Or, Biblical Illustrations Drawn from the Manners and Customs, the Scenes and Scenery, of the Holy Land. Vol. 2 (1st ed.). New York: Harper & brothers – via Internet Archive. pp. 313-314

- Velednizki, Noy (2004-05-31). "el Yavne Final Report". Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel (116). ISSN 1565-5334.

- Volynsky, Felix (2009-06-04). "Tel Yavne Final Report". Excavations and Surveys in Israel. 121. ISSN 1565-5334.

External links

edit- Welcome to Yibna

- Yibna, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 16: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Yibna at Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center

- Yousef Al Hums: 60 Years and Counting, WREMEA, May–June 2008