This article details the history of Adelaide from the first human activity in the region to the 20th century. Adelaide is a planned city founded in 1836 and the capital of South Australia.

Aboriginal settlement

editThe Adelaide plains were inhabited by the Kaurna people before the colonisation of South Australia, their territory extending from what is now Cape Jervis to Port Broughton. The Kaurna lived in family groups called yerta, a word which also referred to the area of land which supported the family group. Each yerta was the responsibility of Kaurna adults who inherited the land and had an intimate knowledge of its resources and features. The Kaurna led a nomadic existence within the Yerta confines in large family groups of around 30.[clarification needed] The area where the Adelaide city centre now stands was called "Tarndanya",[1] which translates as "male red kangaroo rock", an area along the south bank of what is now called the River Torrens. Kaurna numbers were greatly reduced by at least two devastating epidemics of smallpox which preceded European settlement, having been transported downstream along the River Murray. When European settlers arrived in 1836, estimates of the Kaurna population ranged from 300 to 500 people.[2]

British preparation for establishing a colony

editBritish Commander Matthew Flinders and French Captain Nicolas Baudin independently charted the southern coast of the Australian continent, with the notable exception of the inlet later known as the Port Adelaide River. In 1802 Flinders named Mount Lofty, but recorded little of the area which is now Adelaide. In 1830 Charles Sturt explored the River Murray and was impressed with what he briefly saw, later writing:

- "Hurried ....as my view of it was, my eye never fell on a country of more promising aspect, or more favourable position, than that which occupies the space between the lake (Lake Alexandrina) and the ranges of the Gulf St Vincent, and, continuing northerly from Mount Barker stretches away, without any visible boundary".

Captain Collet Barker, sent by New South Wales Governor Ralph Darling, conducted a more thorough survey of the area in 1831, as recommended by Sturt. After swimming the mouth of the Murray River, Barker was killed by Ngarrindjeri people. Despite this, his more detailed survey led Sturt to conclude in his 1833 report:

- "It would appear that a spot has at last been found upon the south coast of New Holland to which the colonists might venture with every prospect of success ... All who have ever landed upon the eastern shore of the St. Vincent's Gulf agree as to the richness of its soil and the abundance of its pastures."

Edward Wakefield

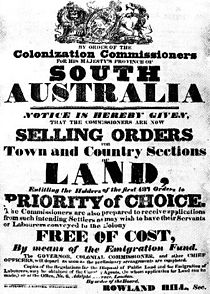

editA group in Britain led by Edward Gibbon Wakefield were looking to start a colony based on free settlement rather than convict labour. After problems in other Australian colonies arising from existing settlement methods, the time was right to form a more methodical approach to establishing a colony. In 1829 an imprisoned Wakefield wrote a series of letters about systematic colonisation which were published in a daily newspaper.

Wakefield suggested that instead of granting free land to settlers as had happened in other colonies, the land should be sold. The money from land purchases would be used solely to transport labourers to the colony free of charge, who were to be responsible and skilled workers rather than paupers and convicts. Land prices needed to be high enough so that workers who saved to buy land of their own remained in the workforce long enough to avoid a labour shortage.

The South Australian Association

editRobert Gouger, secretary of the South Australian Association, promoted Wakefield's theories and organised societies of people interested in the scheme. In 1834 the South Australian Association, with the aid of such figures as George Grote, William Molesworth and the Duke of Wellington persuaded British Parliament to pass the South Australian Colonisation act, succeeding where two previous organisations had failed.

Wakefield wanted the colony's capital to be called Wellington,[citation needed] but King William IV preferred it to be named after his wife, Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen. The British government appointed a Board of Commissioners from people nominated by the South Australian Association, with the task of organising the new colony and meeting the condition of selling at least £35,000 worth of land. This land was advertised and preliminary purchase land orders were sold before a single settler had set foot in their new home.

Free passage was given to suitable labourers, generally men and women under 30 years of age who were healthy and of good character. They were expected to carry out a promise of working for wages until they had saved enough to buy land of their own and employ others, a process taking at least 3 or 4 years. Land sales were encouraged by granting one acre (4,000 m2) of town land in Adelaide for every 80 acres (32 ha) of rural land sold (later altered to 134-acre country sections). The largest buyer of land was the South Australia Company headed by businessman and banker George Fife Angas, which bought enough land for South Australia to proceed, and continued to influence the colony's future development.

With the British government's conditions met, King William IV signed the Letters Patent and the first settlers and officials set sail in early 1836.

British settlement (1836)

editIn February 1836 the vessels John Pirie and Duke of York set sail for South Australia. They were followed in March by Cygnet and Lady Mary Pelham, in April by Emma, in May by Rapid (captained by Colonel Light) and then by Africaine (carrying Robert Gouger) and Tam O'Shanter. The Rapid and Cygnet comprised the Colonization Commissioners for South Australia's 'First Expedition', others took supplies and settlers to Kangaroo Island on the present day site of Kingscote, to await official decisions on the location and administration of the new colony. By the time Duke of York had arrived at Kangaroo Island, HMS Buffalo (carrying Governor John Hindmarsh) was on its way.

Surveyor-General Colonel William Light, who had two months to complete his tasks, rejected locations for the new settlement such as Encounter Bay, Kangaroo Island and Port Lincoln. He was required to find the best site with a harbour, arable land, fresh water, ready internal and external communications, building materials and drainage. Most of the settlers were moved from Kangaroo Island to Holdfast Bay the site of present-day Glenelg, with Governor Hindmarsh arriving on 28 December 1836 to proclaim the commencement of colonial government in South Australia.

Light had to work quickly as the settlers were eager to take possession of the land they had purchased and grew impatient waiting. The salt water Port River was sighted and deemed to be a suitable harbour, however there was no fresh water available nearby. The River Torrens was discovered to the south of the Port River and northeast of Holdfast Bay, and Light and his team set about determining the city's precise location and layout.

Light favoured a location on rising ground along the Torrens valley between the coast and hills which would be free of floodwaters. Governor Hindmarsh upon arrival initially approved of the location, but changed his mind thinking that the site should instead be two miles (3 km) closer to the harbour (an area unsuitable due to flooding). Other colonists thought Port Lincoln or Encounter Bay would be better sites. After much mud slinging, mainly directed towards Light, a public meeting of landholders was called on 10 February 1837, where a vote was held resulting in 218 to 127 in Light's favour, settling the issue for the meantime.

The survey was completed on 11 March 1837, which was a considerable achievement given the time taken to complete comparable surveys. The city plan carefully fitted the topography of the area: the Torrens Valley was kept as parklands and town acres were planned on higher land to the north and south. Adelaide was divided into two districts north and south of the river with North Adelaide composed of 342 acres (1.38 km2) and Adelaide 700 acres (2.8 km2), surrounded by over 2,332 acres (9.44 km2) set aside as parklands for recreation and public functions.[3][4][5]

The grid pattern of South Adelaide's streets features a central square (Victoria Square) and four smaller squares (Hindmarsh, Hurtle, Light and Whitmore). North Adelaide features Wellington Square. Space for public buildings such as Government House, government stores, botanical gardens, hospital, cemetery were included within the Park Lands.[citation needed]

First years

editHindmarsh

editColonists who had already purchased land before departing were given first choice on 23 March 1837, and the remaining areas were auctioned for between 2 and 14 guineas. Within a few weeks many of the same areas were selling for between 80 and 100 pounds which was seen as a healthy sign. With the town survey completed, Light's poorly paid and ill-equipped surveying team were expected to begin another massive task of surveying at least 405 km2 of rural land.

Light's deputy, George Kingston was sent back to London in October 1837 to ask for more staff and equipment to speed up the process, and to have the troublesome Hindmarsh recalled. Light, who was slowly succumbing to tuberculosis, managed to complete 243 km2 (94 sq mi) by December 1837, by which time the population had increased to around 2,500. When Kingston returned in June 1838, 605.7 km2 (233.9 sq mi) had been completed.

Light's requests were denied; instead he could change from the trigonometric surveys to a faster (but inferior) running survey, or hand control over to Kingston and confine himself to coastal surveys. Light resigned in protest. Hindmarsh was to be replaced, and left Adelaide on board Alligator on 14 July 1838, some three months before the next governor, George Gawler, arrived via Kingscote KI, on 12 October 1838, aboard Pestonjee Bomanjee from London.

The first sheep and other livestock in South Australia were brought in from Tasmania. Sheep were overlanded from New South Wales from 1838, with the wool industry forming the basis of South Australia's economy for the first few years. Vast tracts of land were leased by "Squatters" until required for agriculture. Once the land was surveyed it was put up for sale and the Squatters had to buy their runs or move on. Most bought their land when it came up for sale, disadvantaging farmers who had a hard time finding good and unoccupied land.

Farms took longer to establish than sheep runs and were expensive to set up. Despite this, by 1860 wheat farms ranged from Encounter Bay in the south to the Clare Valley in the north.

The city was intended to develop around the central Victoria Square, with the intersecting Grote and King William Streets planned as extra wide to allow for future development. Instead, development concentrated around two of the narrowest streets on the city plan, Rundle and Hindley streets, due to their proximity to the city's water supply and to Port Road, which led directly to the port. Many empty blocks remained until the late 19th century.

Gawler

editAdelaide's second Governor was Colonel George Gawler who arrived in October 1838 to a situation of almost no public finances, underpaid officials and 4,000 immigrants still living in makeshift accommodation. He was allowed a maximum of £12,000 expenditure a year, with an additional £5,000 credit for emergencies, but was given the impression by the Colonial Office back in London that self-sufficiency of the colony was of minor importance and that government support should be relied upon.

Gawler's first goal was to address delays over rural settlement and agriculture. He persuaded Sturt in New South Wales to work for him as surveyor-general, overseeing the surveys himself in the meantime. He appointed more colonial officials with higher wages, set up a police force and took part in explorations of the surrounding terrain. A governor's house, jail, police barracks, hospital, and customs house and wharf at Port Adelaide were built, as well as houses for public officials and missionaries, and outstations for police and surveyors.

The land boom eased after 1839; cash and credit were scarce, explorations indicated limited good land, and British speculators became interested in New Zealand. In 1840 there were crop failures in the other Australian colonies, upon which Adelaide still relied for food, and the cost of living increased rapidly. Gawler increased public expenditure to prevent an economic collapse, which resulted in bankruptcy and later, changes to the way the colony was run (see South Australia Act, 1842). Over £200,000 in bills had been amassed and the land fund in London had been exhausted.

The British Parliament approved a £155,000 loan (later made a gift) to bail-out the colony. A head had to roll and Captain George Grey was sent to replace Gawler. Despite having been recalled, Governor Gawler had put Adelaide on a firm footing, making South Australia agriculturally self-sufficient, building infrastructure such as the Adelaide Gaol, and restoring public confidence.

Grey

editGrey, 29 at the time, issued the news of Gawler's recall himself, from the steps of government house on 15 May 1841. He slashed public expenditure, turning public opinion against him (which Grey ignored). Silver was discovered at Glen Osmond the same year, which lifted spirits and spurred on discoveries of other finds in the Mount Lofty Ranges.

Copper was discovered near Kapunda in 1842. In 1845 even larger deposits of copper were discovered at Burra which brought wealth to the Adelaide shopkeepers who invested in the mine. With a series of good harvests and expanding agriculture, Adelaide exported meat, wool, wine, fruit and wheat.

John Ridley invented a reaping machine in 1843 which changed farming methods throughout South Australia and the nation at large. By 1843, 93 km2 (36 sq mi) of land was growing wheat (contrasted with 0.08 km2, 0.031 sq mi in 1838). Toward the end of the century South Australia became known as the "granary of Australia". From a low point in 1842 when 642 out of 1,915 houses were abandoned and there was talk of abandoning the settlement, Adelaide was a bustling city when Grey left to govern New Zealand in 1845.

1850–1900

editGold discoveries in Victoria in 1851 brought a severe labour shortage due to the exodus of workers leaving to seek their fortunes on the goldfields. However, this also led to a high demand for South Australian wheat. The situation improved when prospectors returned with their gold finds.

South Australians were keen to establish trade links with Victoria and New South Wales, however overland transport was too slow. A£4,000 prize was offered in 1850 by the South Australian government for the first two people to navigate the River Murray in an iron steamboat as far as its junction with the Darling River. In 1853 William Randell of Mannum and Francis Cadell of Adelaide, unintentionally making the attempt at the same time, raced each other to Swan Hill with Cadell arriving first.

South Australia became a self-governing colony in 1856 with the ratification of a new constitution by the British parliament. Secret ballots were introduced, and a bicameral parliament was elected on 9 March 1857, by which time 109,917 people lived in the province.

Premier Robert Torrens devised a land title system in 1858 which adapted the principles of shipping registers, and was emulated in the other Australian colonies and overseas in places such as Singapore. Further copper discoveries were made in 1859 at Wallaroo and in 1861 at Moonta. In 1860 the Thorndon Park reservoir was opened, finally providing an alternative water source to the turbid River Torrens.

During John McDouall Stuart's 1862 expedition to the north coast of Australia, he discovered 200,000 km2 (77,000 sq mi) of grazing territory to the west of Lake Torrens and Lake Eyre. South Australia was made responsible for the administration of the Northern Territory. In 1867 gas street lighting was implemented, the University of Adelaide was founded in 1874, the South Australian Art Gallery opened in 1881 and the Happy Valley Reservoir opened in 1896.

In the 1890s Australia was affected by a severe economic depression, ending a hectic era of land booms and tumultuous expansion. Financial institutions in Melbourne and banks in Sydney closed. The national fertility rate fell and immigration was reduced to a trickle. The value of South Australia's exports nearly halved. Drought and poor harvests from 1884 compounded the problems with some families leaving for Western Australia. Adelaide was not as badly hit as the larger gold-rush cities of Sydney and Melbourne, and silver and lead discoveries at Broken Hill provided some relief. Only one year of deficit was recorded, but the price paid was retrenchments and lean public spending. Wine and copper were the only industries not to suffer a downturn.

Twentieth century

editHistorian F.W. Crowley examined the reports of visitors in the early 20th century:

Many visitors to Adelaide admired the foresighted planning of its founders, but deplored its Puritan tone. Others thought it combined all the best and all the worst features of life in an Australian city – an extremely wealthy upper crust living in splendour in elite suburbs alongside grinding poverty in industrial slums; a nominal proclamation of Christian virtues on Sundays, yet a ruthless devotion to money-making on weekdays.

— F.K. Crowley, Modern Australia in Documents: 1901–1939

Electric street lighting was introduced in 1900 and Adelaide's electric tram service began transporting passengers in 1909.

28,000 South Australians volunteered to fight during Australia's involvement in the First World War. Adelaide enjoyed a post-war boom, but with the return of droughts, entered the depression of the 1930s, later returning to prosperity with strong government leadership.[citation needed]

In 1928, 2000 special constables were sworn in to break a strike of dock workers. The volunteer "Citizen's Defence Brigade" had been brought in and armed to fight striking port workers, and they were housed in a camp dubbed the "scab compound".[6]

Secondary industries helped reduce the state's dependence on primary industries. The 1933 census recorded the state population at 580,949, which was less of an increase than other states due to the state's economic limitations.

In 1935 Goldsbrough Mort and Company built their multi-storey premises on North Terrace.[7]

World War II brought industrial stimulus and diversification to Adelaide under the leadership of Thomas Playford. 70,000 men and women enlisted and shipbuilding was expanded at Whyalla. Adelaide's transformation from an agricultural service centre to a 20th-century city was under way.

Post world war II

editAfter the war, an assisted migration scheme brought 215,000 emigrants of many European nationalities to South Australia between 1947 and 1973. Electrical goods were manufactured in former munitions factories and Holden cars were manufactured from 1948. An earthquake did considerable damage in March 1954. The Mannum–Adelaide pipeline brought River Murray water to Adelaide in 1955 and Adelaide Airport opened at West Beach in 1955. Adelaide gained a second university in 1966 with the opening of Flinders University.

In 1968, a blueprint for the building an integrated system of freeways across Adelaide was released in the form of the Metropolitan Adelaide Transport Study (MATS). Bowing to opposition from the public, who feared freeways would create urban problems such as gridlocked traffic and ghettos, the Labor government under Don Dunstan shelved MATS but retained the land in case public opinion changed in the future.[8] In 1980, the Liberal party won government on a platform of fiscal conservatism and the premier David Tonkin, deeming Adelaide road capacities sufficient for future needs, committed his government to selling off the land acquired for the MATS plan ensuring that even when needs or public opinion changed, the construction of most MATS proposed freeways would be impossible.[9]

The Dunstan Government of the 1970s saw something of an Adelaide 'cultural revival' - establishing a wide array of social reforms and overseeing the city becoming a centre of the arts. Adelaide hosted the Australian Grand Prix between 1985 and 1996 on the Adelaide Street Circuit in the city's east parklands, before losing it in a controversial move to Melbourne. The (Old) Adelaide Gaol was closed in 1988.

In 1989, the Australian Submarine Corporation naval shipyards were opened.[10] In 1991, the University of South Australia was formed from a merger of several state government education institutions.

The 1992 A$3.1 billion State Bank collapse plunged both Adelaide and South Australia into economic recession, was the biggest banking crisis in Australia since the great bank crashes in Victoria in the 1890s, the economic effects are still felt today. [11] This resulted in the resignation of John Bannon, who was at that time both Premier and Treasurer (1982–1992); in the resulting 1993 election, the Liberal party won what is still the largest majority government in South Australian history of 23 seats.[citation needed]

Twenty-first century

editFrom 1999 until 2020, the Adelaide 500 Supercars race used part of the Adelaide Street Circuit and renewed economic confidence under the Rann government.[citation needed] The late first decade of the 21st century have seen extensions of the remaining tram network, the first growth after the decline of the system during the 1950s. The western end of North Terrace was revitalised after the relocation of the Royal Adelaide Hospital from the eastern end in 2017, as well as the subsequent opening of the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute (SAHMRI), the University of Adelaide Health and Medical Sciences building, the University of South Australia's Health Innovation Building and various other health and biomedical research institutes under construction, leading to the informal moniker of the western end of North Terrace as Adelaide's "BioMed City" precinct. Much of this land was formerly railyards.

See also

edit- Timeline of Adelaide history

- Light's Vision

- Proclamation Day

- Australian Overland Telegraph Line

- Street Naming Committee (Adelaide)

- The Old Gum Tree

- Old Government House, Belair

People

editReferences

edit- ^ "Tarndanya", KauranaPlaceNames.com. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- ^ Mattingley, C. and Hampton, K. (eds., 1988) Survival in our own land: 'Aboriginal' experiences in South Australia since 1836. Wakefield Press. p. 5. ISBN 0859040402

- ^ "Town Acre Reference Map - Map of the City of Adelaide". data.sa.gov.au. 5 June 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2021. PDF

- ^ Elton, Jude (10 December 2013). "Light's Plan of Adelaide, 1840". Adelaidia. History Trust of South Australia. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ Llewellyn-Smith, Michael (2012). "The Background to the Founding of Adelaide and South Australia in 1836". Behind the Scenes: The Politics of Planning Adelaide. University of Adelaide Press. pp. 11–38. ISBN 9781922064400. JSTOR 10.20851/j.ctt1sq5wvd.8. Retrieved 16 January 2021 – via JSTOR.

- ^ "Port Adelaide struggles, 1928-1931". libcom.org. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ The City of Adelaide: a thematic history (PDF). McDougall & Vines. 2006. p. 21.

- ^ Eric Franklin, The Advertiser: Labour Will Revise MATS Plan, 6 May 1970

- ^ "Adelaide's Freeways: A History from MATS to the Port River Expressway". OZROADS. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ Yule & Woolner, The Collins Class Submarine Story, p. 127

- ^ "'Don't have state banks', says man who witnessed black day for SA". Australian Financial Review. 24 February 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

Further reading

edit- Ray Broomhill, "Underemployment In Adelaide During The Depression." Labour History. Nov 1974, Issue 27, p31-40. On 1930s

- Elizabeth Kwan Living in South Australia: A Social History Volume 1: From Before 1836 to 1914 (1987)

- Kathryn Gergett and Susan Marsden Adelaide: A brief History (1996)

- Derek Whitelock Adelaide: From Colony to Jubilee (1985)

- Steuart, Archibald Francis (1901). A short sketch of the lives of Francis and William Light: the founders of Penang and Adelaide, with extracts from their journals. Sampson Low, Marston & Co.