The Swedish health care system is mainly government-funded, universal for all citizens and decentralized,[1] although private health care also exists. The health care system in Sweden is financed primarily through taxes levied by county councils and municipalities. A total of 21 councils are in charge with primary and hospital care within the country.

Private healthcare is a rarity in Sweden, and even those private institutions work under the mandated city councils.[2] The city councils regulates the rules and the establishment of potential private practices. Although in most countries care for the elderly or those who need psychiatric help is conducted privately, in Sweden local, publicly funded authorities are in charge of this type of care.[3]

Management

editSweden's health care system is organized and managed on three levels: national, regional and local. At the national level, the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs establishes principles and guidelines for care and sets the political agenda for health and medical care. The ministry, along with other government bodies, supervises activities at the lower levels, allocates grants, and periodically evaluates services to ensure correspondence to national goals.

Regional responsibility for financing and providing health care is decentralized to the 21 county councils. A county council is a political body whose representatives are elected by the public every four years on the same day as the national general election. The executive board or hospital board of a county council exercises authority over hospital structure and management and ensures efficient health care delivery. County councils also regulate prices and the level of service offered by private providers. Private providers are required to enter into a contract with the county councils. Patients are not reimbursed for services from private providers who do not have an agreement with the county councils. According to the Swedish health and medical care policy, every county council must provide residents with good-quality health services and medical care and work toward promoting good health in the entire population.

At the local level, municipalities are responsible for maintaining the immediate environment of citizens, such as water supply and social welfare services. Recently, post-discharge care for the disabled and elderly and long-term care for psychiatric patients was decentralized to the local municipalities.

County councils have considerable leeway in deciding how care should be planned and delivered. This explains the wide regional variations.

It is informally divided into 7 sections: "Close-to-home care" (primary care clinics, maternity care clinics, out-patient psychiatric clinics, etc.), emergency care, elective care, in-patient care, out-patient care, specialist care, and dental care.[4]

All citizens are to be given on line access to their own electronic health records by 2020. Many different record systems are used which has caused problems for interoperability. A national patient portal, ‘1177.se’ is used by all systems, with both telephone and online access. At June 2017 about 41% of the population had set up their own account to use personal e-services using this system. A national Health Information Exchange platform provides a single point of connectivity to the many different systems. There is not yet a national regulatory framework for patients’ direct access to their health information.[5]

Provision

editPrivate companies in 2015 provide about 20% of public hospital care and about 30% of public primary care, although in 2014 a survey by the SOM Institute found that 69% of Swedes were opposed to private companies profiting from providing public education, health, and social care, with only about 15% actively in favour.

In April 2015 Västernorrland County ordered its officials to find ways to limit the profits private companies can reap from running publicly funded health services.[6]

Financing

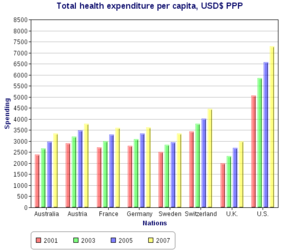

editCosts for health and medical care amounted to approximately 9 percent of Sweden's gross domestic product in 2005, a figure that remained fairly stable since the early 1980s. By 2015 the cost had risen to 11.9% of GDP -the highest in Europe.[7] Seventy-one percent of health care is funded through local taxation, and county councils have the right to collect income tax. The state finances the bulk of health care costs, with the patient paying a small nominal fee for examination. The state pays for approximately 97% of medical costs.[8]

When a physician declares a patient to be ill for whatever reason (by signing a certificate of illness/unfitness), the patient is paid a percentage of their normal daily wage from the second day. For the first 14 days, the employer is required to pay this wage, and after that the state pays the wage until the patient is declared fit.

The funding and cost of keeps healthcare affordable and accessible to all Swedish citizens.[9] Local taxes equate for about 70% of the budgets for councils and municipalities, while overall 85% of the total health budget come from public funding.[10]

Details and patient costs

editPrescription drugs are not free but fees to the user are capped at 2350 SEK per annum. Once a patient's prescriptions reach this amount, the government covers any further expenses for the rest of the year. The funding system is automated. The country's pharmacies are connected over the Internet. Each prescription is sent to the pharmacy network, which stores information on a patient's medical history and on the prescriptions fulfilled previously for that patient. If the patient's pharmaceutical expenses have exceeded the annual limit, the patient receives the medication free of charge at the point of sale, upon producing identification.

In a sample of 13 developed countries Sweden was eleventh in its population weighted usage of medication in 14 classes in 2009 and twelfth in 2013. The drugs studied were selected on the basis that the conditions treated had high incidence, prevalence and/or mortality, caused significant long-term morbidity and incurred high levels of expenditure and significant developments in prevention or treatment had been made in the last 10 years. The study noted considerable difficulties in cross border comparison of medication use.[11]

A limit on health-care fees per year exists; 150-400 SEK for each visit to a doctor, regardless if they are a private doctor or work at a local health-care center or a hospital. When visiting a hospital, the entrance fee covers all specialist visits the doctor deems necessary, like x-ray, rheumatism specialist, heart surgery operations and so on. The same fee is levied for ambulance services. After 1150 SEK have been paid, health-care for the rest of the year will be provided free of charge.

Dental care is not included in the general health care system, but is partly subsidized by the government. Dental care is free for citizens up to 23 years of age.

Mental health care is an integrated part of the health care system and is subject to the same legislation and user fees as other health care services. If an individual has minor mental health issues, they are attended to by a GP in a primary health setting; if the patient has major mental health issues they are referred to specialized psychiatric care in hospitals.[12]

Performance

editThe system of investigating incidents in maternity care has been very successful. It starts with a no-blame investigation, which is completed quickly. There is then a consideration of whether the problem was avoidable, and if they were how the learning from the incident can be used. Families get compensation if it was avoidable, usually without going to court.[13]

Waiting times

editUrgent cases are always prioritized and emergency cases are treated immediately. The national guarantee of care, Vårdgaranti, lays down standards for waiting times for scheduled care, aiming to keep waiting time below 7 days for a visit to a primary care physician, and no more than 90 days for a visit to a specialist.[14]

According to the Euro health consumer index the Swedish score for technically excellent healthcare services, which they rated 10th in Europe in 2015, is dragged down by access and waiting time problems, in spite of national efforts such as Vårdgaranti. It is claimed that there is a long tradition of steering patients away from their doctor unless they are really sick.[15]

A shortage of medical personnel is a major problem.[16]

Private healthcare

editAccording to Nima Sanandaji, at the end of 2017, 643,000 individuals in Sweden were fully covered by private health insurance, which is 6.5% of the population of Sweden. This is an increase of over half a million fully covered by private health insurance compared to 2000.[17]

Criticisms

editThe Swedish health system is mainly effective but there are some problems within the system.[18] The decentralized healthcare system in Sweden leads to this inefficiency, because of decentralization the counties are granted an extreme amount of flexibility. The coordination between regions and municipalities is affected because of this constant shifting and flexibility.[19] Variation between outcomes and access to care in different regions has been highlighted as a weakness of the system by Socialstyrelesen.[20]

In recent years the health care system of Sweden has been heavily criticized for not providing the same quality of health care to all Swedish citizens. The disparity of health care quality in Sweden is growing. Swedish citizens of other ethnicities than Swedish, and citizens who are of a lower socio-economic class, receive a significantly lower quality of health care than the rest of the population.[21][22][23][24] This was especially brought to light during the COVID-19 pandemic, as Swedish media and public health researchers pointed out that Swedish citizens of other ethnicities than Swedish, and people living in working class areas, were dying from COVID-19 at a significantly higher rate than the rest of the population, due to the fact that they were not provided with the same quality of health care.[25][26][27]

The Health and Social Care Inspectorate (Ivo) report

editIn January 2023 the IVO announced the results of its inspection of 27 hospitals around the country. This report concluded that the current system could not adequately guarantee patient safety in any of the hospitals inspected. Peder Carlsson, the unit chief at IVO who led the inspection said: “Patients do not get an acceptable amount of food, fluids or basic treatment, and according to our information, patients can be required to lie for several hours in their own faeces and urine.” Swedish news agency TT quoted Carlsson as saying: “This is a terrible situation, totally unacceptable and it is particularly striking that this is happening in the hospitals we have in our country".[28][29][30]

See also

edit- Health in Sweden

- Health care compared - tabular comparisons with the US, Canada, and other countries not shown above.

- Vårdguiden 1177

References

edit- ^ "Getting Better Value for Money from Sweden's Healthcare System | OECD READ edition". OECD iLibrary. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ^ "Improving Quality and Value for Money in Healthcare | OECD READ edition". OECD iLibrary. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ^ Orange, Richard (2015-04-28). "Swedish council becomes first to limit private profits in healthcare". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ^ Mittag, Ann-Marie (2008-11-25). "Hälso- och sjukvård" (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 2011-05-24. Retrieved 2009-03-15.

- ^ Hägglund, Maria (30 October 2017). "How Sweden is giving all citizens access to their electronic health records". Future Health Index. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ "Swedish council becomes first to limit private profits in healthcare". Guardian. 28 April 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ^ Ballas, Dimitris; Dorling, Danny; Hennig, Benjamin (2017). The Human Atlas of Europe. Bristol: Policy Press. p. 79. ISBN 9781447313540.

- ^ Glenngard, A., Hjalte, F., Svennson, M., Anell, A., & Bankauskaite, V. (2005). Health Systems in Transition: Sweden. WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2005

- ^ Anell, Anders (February 2008). "The Swedish Healthcare System" (PDF). The Commonwealth Fund.

- ^ Rodriguez, Linda (2009). "Swedish Socialism" (PDF). Spinning the Globe: Sweden. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ^ Office of health Economics. "International Comparison of Medicines Usage: Quantitative Analysis" (PDF). Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ "The Swedish Health Care System". Retrieved 2018-10-17.

- ^ Hunt, Jeremy (2022). Zero. London: Swift Press. p. 126. ISBN 9781800751224.

- ^ "Vårdgaranti".

- ^ "Outcomes in EHCI 2015" (PDF). Health Consumer Powerhouse. 26 January 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ "Sweden's healthcare system bogged down by shortage of doctors, nurses". Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- ^ So Long, Swedish Welfare State?

- ^ "OECD Economic Surveys: Sweden 2005 | OECD READ edition". OECD iLibrary. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ^ Svanborg-Sjövall, Karin (2014-01-03). "Swedish healthcare is the best in the world, but there are still lessons to learn". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ^ "Goda medicinska resultat men fortsatta problem med tillgång till vård". Socialstyrelsen (in Swedish). 2020-02-20. Retrieved 2023-11-16.

- ^ "Svenskarna lever länge men hälsan är ojämlik i landet". Folkhälsomyndigheten. January 22, 2020. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ "Sjukvårdens struktur bidrar till ojämlik vård". Läkartidningen. June 15, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ "Arbete för jämlik hälsa i Sverige nationellt, regionalt och lokalt". Idunn. January 1, 2016. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ "Ojämlik vård – dags för verkstad". Life-time. March 26, 2015. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ "Risk of dying from COVID-19 in Sweden is greater for men and the unmarried". Stockholm University. October 9, 2020. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ "Covid-19 vanligare i utsatta områden - är sårbarhet för sjukdomar en klassfråga?". Stockholm University. April 24, 2020. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ "Corona härjar bland fattiga – rika klarar sig". Expressen. April 24, 2020. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ "Situation in Sweden's hospitals 'terrible and completely unacceptable': watchdog". Local Sweden.

- ^ IVO.se. "IVO:s nationella sjukhustillsyn: Patientsäkerheten kan inte garanteras". IVO.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 2023-11-16.

- ^ "Bara 4 av 15 sjukhus får godkänt av Ivo – fortsatt allvarliga brister". www.vardfokus.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 2023-11-16.

External links

edit- Vårdguiden (The Care Guide) - EU-regulated health care website by the Stockholm health care system.