Elias Cornelius Boudinot (August 1, 1835 – September 27, 1890) was an American politician, lawyer, newspaper editor, and co-founder of the Arkansan who served as the delegate to the Confederate States House of Representatives representing the Cherokee Nation. Prior to this he served as an officer of the Confederate States Army in the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War. He was the first Native American lawyer permitted to practice before the U.S. Supreme Court.[1]

E. C. Boudinot | |

|---|---|

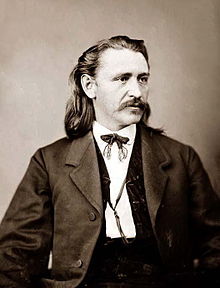

Boudinot, c. 1860 | |

| Delegate to the C.S. House of Representatives from the Cherokee Nation's at-large district | |

| In office February 18, 1862 – May 10, 1865 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | Constituency abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Elias Cornelius Boudinot August 1, 1835 New Echota, Cherokee Nation (present-day Gordon County, Georgia), U.S. |

| Died | September 27, 1890 (aged 55) Fort Smith, Arkansas, U.S. |

| Resting place | Oak Cemetery, Fort Smith, Arkansas, U.S. 35°22′10.3″N 94°24′06.8″W / 35.369528°N 94.401889°W |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Clara C. Boudinot (m. 1885) |

| Parent(s) | Elias Boudinot (father) Harriet Boudinot (mother) |

| Relatives | Stand Watie (uncle) |

| Education | Burr Seminary |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Confederate States |

| Branch | Confederate States Army |

| Years of service | 1861–1862 |

| Rank | Major |

| Unit | 2d Cherokee Mounted Rifles |

| Battles | |

He was the mixed-race son of Elias and Harriet Ruggles (née Gold) Boudinot, who was from Connecticut. His father was editor of the Cherokee Phoenix, the first Native American newspaper, which was published in Cherokee and English. In 1839 his father and three other leaders were assassinated by opponents in the tribe as retaliation for having ceded their homeland in the 1835 Treaty of New Echota. The Boudinot children were orphaned by their father's murder, as their mother had died in 1836. They were sent for their safety to their mother's family in Connecticut, where they were educated.

Following the Civil War, Boudinot participated in negotiations of the Southern Cherokee with the United States before the tribe was reunited; he was part of the Cherokee delegation to the US. In 1868 he and his uncle Stand Watie opened a tobacco factory, to take advantage of provisions under the nation's new 1866 treaty with the United States. It was confiscated for non-payment of taxes, and their case went to the United States Supreme Court, which ruled against them. Boudinot began to lobby for Native Americans to be granted United States citizenship in order to be protected by the Constitution.

He was active in politics and society in the Indian Territory and Washington, D.C., supporting construction of railroads in the territory. Boudinot also worked for two Arkansas politicians. He supported proposals for termination of Cherokee sovereignty and the allotment of communal land to tribal members, as was passed under the Dawes Act. As this would extinguish tribal land rights, Boudinot also worked to establish the state of Oklahoma and have it admitted to the Union. In his 2011 history of America's transcontinental railroads, historian Richard White writes of Boudinot: "[He] became a willing tool of the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad.... If the competition were not so stiff, Boudinot might be ranked among the great scoundrels of the Gilded Age."[2]

Early life and education

editBorn August 1, 1835, at New Echota, Cherokee Nation (present-day Gordon County, Georgia); Elias Cornelius Boudinot was the son of Elias, a Cherokee National leader, and his wife Harriet Ruggles (née Gold) Boudinot (1805–1836), a young woman of English-American descent from a prominent family in Cornwall, Connecticut. They had met there when his father was a student at a local school for Native Americans. The senior Elias Boudinot became editor of the Cherokee Phoenix from 1828-1832; it was the first newspaper founded by a Native American nation and published in their language. He published articles in English and Cherokee, and had type cast for the syllabary created by Sequoyah. The newspaper was distributed across the United States and internationally.

His parents named this son Elias Cornelius Boudinot, after the missionary Elias Cornelius, who had selected his father to attend the Foreign Mission School in Connecticut. Elias was the fifth of six children.[3] The year the boy was born, his father and other leaders had signed the Treaty of New Echota, ceding the remainder of Cherokee lands in the Southeast in exchange for removal to Indian Territory and lands west of the Mississippi River. Boudinot's mother Harriet died in 1836, several months after her seventh child was stillborn. The family moved to Indian Territory prior to the forced removal of 1838.

In 1839, when Boudinot was four years old, his father and other Treaty Party leaders were assassinated by Cherokee opponents for having given up the communal tribal lands, which was considered a capital offense. His uncle Stand Watie survived an attack the same day. For their safety, Boudinot and his siblings were sent back to Connecticut to their mother's family. The Golds ensured the children received good educations. As a youth, Boudinot studied engineering in Manchester, Vermont.[3]

Career

editIn 1851 at age eighteen, Boudinot returned West and taught school briefly. In 1853 he settled in Fayetteville, Arkansas near the Cherokee, and renewed contact with his uncle Stand Watie. He studied as a legal apprentice and passed the bar in 1856 in Arkansas.[4] His first notable victory as a lawyer was defending his uncle Stand Watie against murder charges. Watie had killed James Foreman, one of the attackers of Major Ridge, Watie's uncle. Major Ridge, his son John Ridge and Boudinot's father had all been assassinated in 1839. Watie had survived the attack. Boudinot wanted to revive his family's prominence among the Cherokee.[3]

In Arkansas, Boudinot became active as a pro-slavery advocate in the Democratic Party; this was the majority position of party members. He was elected to the city council of Fayetteville in 1859.[3] That year, together with James Pettigrew, he founded a pro-slavery newspaper, The Arkansan. It also favored the construction of railroads into Indian Territory, which was seen as integral to development. Many American Indians did not want their territory broken up by such intrusions. Boudinot urged the territory to regularize its status with the United States, and later supported measures needed to admit Oklahoma as a state.[4]

American Civil War

editThe following year Boudinot was chosen as the chairman of the Arkansas Democratic State Central Committee and monitored rising tensions in the country. In 1861, he served as the secretary of the Secession Convention as the Arkansas Territory determined whether it would leave the Union. He also served in the 2d Cherokee Mounted Rifles under his uncle Stand Watie. Boudinot was elected major of the regiment. In 1862, he was elected a delegate to the Confederate States House of Representatives, representing the majority faction of the Cherokee who supported the Confederacy. (A minority supported the Union.)[3] After the war, he was chairman of the Cherokee Delegation (south) to the Southern Treaty Commission, which had to renegotiate their treaties postwar with the United States. They were forced to cede territory, emancipate their slaves, and to offer full citizenship to Cherokee Freedmen who chose to stay with the nation, in a pattern similar to that which the United States required of the former states in rebellion.

Later years

editFollowing the war, Boudinot and his uncle Stand Watie started a tobacco factory. They intended to take advantage of tax immunities in the 1866 Cherokee treaty with the United States. As the majority of Cherokee had supported the Confederacy, the US required them to make a new peace treaty. Disagreeing that the 1866 treaty provided immunity for such operations as the tobacco factory, US officials seized the factory for nonpayment of taxes. In 1871, the US Supreme Court ruled against Boudinot and Watie. It said that the Congress could abrogate previous treaty guarantees, and that the 1866 treaty had not renewed or provided for previous tax immunities.[3]

Boudinot continued to be active in politics and society in Indian Territory after the war. He helped attract railroad construction. Under changing Indian policy by the federal government, he helped open the former Indian Territory to white settlement with passage of the Dawes Act. It first provided for allotment of communal lands to individual households of tribal members. The federal government declared any remaining land as "surplus" and allowed its sale to non-Native Americans. Boudinot founded the city of Vinita, Oklahoma.[3]

He also spent time lobbying the federal government in Washington, DC. Among his activities was lobbying for the railroads. Congress passed a bill in 1873 to provide financial relief for Boudinot. However, this bill was pocket vetoed by President Ulysses S. Grant.[5] Beginning in 1874, Boudinot served as private secretary to Congressman Thomas M. Gunter (D-Arkansas). He also was appointed to some paid committee clerkships. After Gunter left Congress, Boudinot became the secretary to U.S. Senator James David Walker of Arkansas. In 1885, he tried to gain appointment as Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Although supported by Arkansas politicians, he was unsuccessful.[6]

He also practiced law in Arkansas with the politician Robert Ward Johnson (1814-1879), who had been elected to both houses of Congress before the Civil War. Boudinot was active politically on issues related to the Indian Territory. He frequently spoke on the lecture circuit about Cherokee issues and development in the West, and was considered a prominent orator.[3] Boudinot contributed to the eventual formation of the state of Oklahoma in the early twentieth century. Many Cherokee and others of the Five Civilized Tribes had first tried to gain passage of legislation to found a state to be controlled by Native Americans.[3] He continued his work as an attorney. He died at the age of 55 of dysentery in Fort Smith on September 27, 1890. He is buried in Oak Cemetery.[6]

Personal life

editBoudinot did not marry until 1885, when he was 50. He married Clara Minear; they had no children. After their marriage, they moved to Fort Smith, Arkansas, and lived there for the rest of their years.

References

edit- ^ "Widow of Indian Lawyer, Former Resident of Washington". The Evening Star. Washington, D.C. September 25, 1911. p. 18. Retrieved June 23, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Richard White (2011). Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America. National Geographic Books. ISBN 978-0-393-34237-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i James W. Parins (2005). Elias Cornelius Boudinot: A Life on the Cherokee Border. American Indian Lives. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-3752-0.

- ^ a b John Reyhner, Review: Elias Cornelius Boudinot: A Life on the Cherokee Border, Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Vol. 111, No. 1, July 2007, accessed 7 August 2012

- ^ Presidential Vetoes, 1789-1988 (PDF). U.S. Senate. p. 46.

- ^ a b Thomas Burnell Colbert, "Elias Cornelius Boudinot", Encyclopedia of Arkansas, 2009, accessed 7 August 2012

Further reading

edit- Adams, John D. Elias Cornelius Boudinot: In Memoriam, Chicago: Rand McNally, 1890.

- Colbert, Thomas Burnell. Prophet of Progress: The Life and Times of Elias Cornelius Boudinot, PhD diss., Oklahoma State University, 1982.

- Sharon O'Brien (February 2000). "Boudinot, Elias Cornelius". American National Biography Online. Retrieved June 7, 2006.

- ———. "Visionary or Rogue: The Life and Legacy of Elias Cornelius Boudinot," Chronicles of Oklahoma 65 (Fall 1987): 268–281.