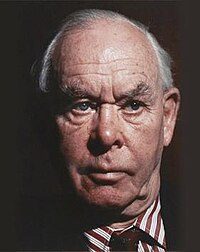

Edward John Mostyn Bowlby, CBE, FBA, FRCP, FRCPsych (/ˈboʊlbi/; 26 February 1907 – 2 September 1990) was a British psychiatrist, and psychoanalyst, notable for his interest in child development and for his pioneering work in attachment theory. A Review of General Psychology survey, published in 2002, ranked Bowlby as the 49th most cited psychologist of the 20th century.[1][2][3]

John Bowlby | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Edward John Mostyn Bowlby 26 February 1907 |

| Died | 2 September 1990 (aged 83) |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Cambridge, University College Hospital |

| Known for | Pioneering work in attachment theory |

| Awards | CBE, FRCP |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Psychology, Psychiatry |

| Institutions | Maudsley Hospital, Tavistock Clinic, World Health Organization |

Family background

editBowlby was born in London to an upper-middle-income family. He was the fourth of six children and was brought up by a nanny in the British fashion of his class at that time: the family hired a nanny who was in charge of raising the children, in a separate nursery in the house.[4] Nanny Friend took care of the infants and generally had two other nursemaids to help her. Bowlby was raised primarily by nursemaid Minnie who acted as a mother figure to him and his siblings.[4]

His father, Sir Anthony Alfred Bowlby, was surgeon to the King's Household, with a history of early loss: at age five, Anthony's father, Thomas William Bowlby, was killed while serving as a war correspondent in the Second Opium War.[5]

Bowlby's parents met at a party in 1897 through a mutual friend. About one year after meeting, Mary (age 31) and Anthony (age 43) decided to get married in 1898. The start of their marriage was said to be difficult due to conflict with Anthony's sister and physical separation between Mary and Anthony.[4] To resolve this prolonged separation, Mary decided to visit her husband for six months while leaving her firstborn daughter Winnie in the care of her nanny.[4] This separation between Mary and her children was a theme found in all six of her children's lives as they were primarily raised by the nanny and nursemaids.[4]

Normally, Bowlby saw his mother only one hour a day after teatime, though during the summer she was more available. Like many other mothers of her social class, she considered that parental attention and affection would lead to dangerous spoiling of the children. Bowlby was fortunate in that the family nanny was present throughout his childhood.[6] When Bowlby was almost four years old, the nursemaid Minnie, his primary caregiver in his early years, left the family. Later, he was to describe this as tragic as the loss of a mother.[4] After Minnie left, Bowlby and his siblings were cared for by Nanny Friend, of a colder and sarcastic nature.[4]

During World War I, Bowlby's father Anthony was on military service. He came home once or twice a year and had little contact with him and his siblings. His mother received letters from Anthony but she did not share them with her children.[4]

At the age of seven, Bowlby was sent to boarding school, as was common for boys of his social status. Bowlby's parents decided to send both him and his older brother Tony to a prep school, to protect them from the bombing attacks due to the ongoing war.[4] In his 1973 work Separation: Anxiety and Anger, Bowlby wrote that he regarded it as a terrible time for him. He later said, "I wouldn't send a dog away to boarding school at age seven".[7] However, earlier Bowlby had considered boarding schools appropriate for children aged eight and older. In 1951, he wrote:

If the child is maladjusted, it may be useful for him to be away for part of the year from the tensions which produced his difficulties, and if the home is bad in other ways the same is true. The boarding school has the advantage of preserving the child's all-important home ties, even if in slightly attenuated form, and, since it forms part of the ordinary social pattern of most Western communities today [1951], the child who goes to boarding school will not feel different from other children. Moreover, by relieving the parents of the children for part of the year, it will be possible for some of them to develop more favorable attitudes toward their children during the remainder.[8]

Bowlby married Ursula Longstaff, the daughter of a surgeon, on 16 April 1938, and they had four children, including Sir Richard Bowlby, who succeeded his uncle as third Baronet.[9]

Bowlby died at his summer home on the Isle of Skye, Scotland.[citation needed]

Career

editIn an interview with Dr. Milton Stenn in 1977,[10] Bowlby explained that his career started off in the medical direction as he was following in his surgeon father's footsteps. His father was a well-known surgeon in London and Bowlby explained that he was encouraged by his father to study medicine at Cambridge. Therefore, he followed his father's suggestion, but was not fully interested in the lessons in anatomy and natural sciences that he was reading about. However, during his time at Trinity College, he became particularly interested in developmental psychology, which led him to give up medicine by his third year. When Bowlby gave up medicine, he took a teaching opportunity at a school called Priory Gates for six months where he worked with maladjusted children. Bowlby explained that one of the reasons why he went to work at Priory Gates was because of an intelligent staff member, John Alford. Bowlby explained that the experience at Priory Gates was extremely influential on him "It suited me very well because I found it interesting. And when I was there, I learned everything that I have known; it was the most valuable six months of my life, really. It was analytically oriented".[11] He further explained that the experience at Priory Gates was extremely influential to his career in research as he learned that the problems of today should be understood and dealt with at a developmental level.

Bowlby studied psychology and pre-clinical sciences at Trinity College, Cambridge, winning prizes for outstanding intellectual performance. After Cambridge, he worked with maladjusted and delinquent children until, at the age of twenty-two, he enrolled at University College Hospital in London. At twenty-six, he qualified in medicine. While still in medical school, he enrolled himself in the Institute for Psychoanalysis. Following medical school, he trained in adult psychiatry at the Maudsley Hospital. In 1936, aged 30, he qualified as a psychoanalyst.

During the first six months of World War II, Bowlby worked at the London Child Guidance clinic in Canonbury as a physician.[10] Later on in the war, Bowlby became a lieutenant colonel in the Royal Army Medical Corps, where he conducted research on psychological methods of officer selection (which contributed to the creation of War Office Selection Boards) and where he came into contact with members of the Tavistock Clinic. Alongside his job in the Royal Army Medical Corps, Bowlby explained that he also worked for the Emergency Medical Services (EMS) during the months of May and June in 1940 where he dealt with tragic war neurosis cases.[10] Additionally, the children that were being treated at the Canonbury clinic were evacuated to the child guidance clinic in Cambridge, due to the air raids from the War.[10] Bowlby explained in an interview that he spent time going back and forth from Cambridge to London, where he would see patients in private.[10] From this experience, Bowlby was able to work with several children at Cambridge that were evacuated from London and separated from their families and nannies. This actually extended his research on separation that he was focused on pre-war.

During the first winter of World War II, Bowlby began working on his first published work Forty-four Juvenile Thieves.[10] Although he began working on this book at the beginning of the Second World War, it was not published until 1944. Bowlby studied several children during his time at the Canonbury clinic, and developed a research project based on case studies of the children's behaviors and family histories.[10] Bowlby examined 44 delinquent children from Canonbury who had a history of stealing and compared them to "controls" from Canonbury that were being treated for various reasons but did not have a history of stealing.[12] Bowlby categorized the delinquent children into six different character types which included: normal, depressed, circular, hyperthymic, affectionless, and schizoid.[12]

One of Bowlby's main findings through his research with these children was that 17 out of the 44 thieves experienced early and prolonged separation (six months or more) from their primary caregiver before the age of five.[12] In comparison, only two out of the 44 children who did not steal had experienced prolonged separation from their primary caregiver before the age of five.[12] More specifically, Bowlby found that 12 out of the 14 children who were categorized as affectionless were found to have experienced complete and prolonged separation before the age of five.[12] These findings were important and brought more attention to the impact of early environmental experiences on healthy child development.

After the war, he was deputy director of the Tavistock Clinic, and from 1950, Mental Health Consultant to the World Health Organization. Because of his previous work with maladapted and delinquent children, he became interested in the development of children and returned to work at the London Child Guidance Clinic in Islington.[13] His interest was probably increased by a variety of wartime events involving separation of young children from familiar people. These included the rescue of Jewish children by the Kindertransport arrangements, the evacuation of children from London to keep them safe from air raids, and the use of group nurseries to allow mothers of young children to contribute to the war effort.[14] Bowlby was interested from the beginning of his career in the problem of separation, the wartime work of Anna Freud and Dorothy Burlingham on evacuees, and the work of René Spitz with orphans.[citation needed]

By the late 1950s, he had accumulated a body of observational and theoretical work to indicate the fundamental importance for human development of attachment from birth.[7] He contributed evidence to the Platt Report 1959 about how separation from mother whilst in hospital could be harmful to children.[15]

Bowlby was interested in finding out the patterns of family interaction involved in both healthy and pathological development. He focused on how attachment difficulties were transmitted from one generation to the next. In his development of attachment theory, he proposed the idea that attachment behaviour was an evolutionary survival strategy for protecting the infant from predators. Mary Ainsworth joined Bowlby's research unit at Tavistock[16] and further extended and tested his ideas. She played the primary role in suggesting that several attachment styles existed.

Seven important experiences for Bowlby's future work and the development of attachment theory were:

- Bowlby's teaching experience at Priory Gates School, where he worked with maladapted and delinquent children.[10]

- His opportunity to work with children who were evacuated from their families due to the war, leading to his work on the forty-four juvenile thieves.[10]

- The addition of an ethology perspective to his thoughts and observations of mother-child separations, which helped him move beyond a psychoanalytic perspective.[16]

- Mary Ainsworth's structured observation technique known as strange situation and the development of the different types of attachment styles as well as her contributions and introduction of the secure base to Bowlby.[17]

- James Robertson (in 1952) in making the documentary film A Two-Year Old Goes to Hospital, which was one of the films about "young children in brief separation".[18] The documentary illustrated the impact of loss and suffering experienced by young children separated from their primary caretakers. This film was instrumental in a campaign to alter hospital restrictions on visiting by parents. When he and Robertson presented their film A Two Year Old Goes to Hospital to the British Psychoanalytical Society in 1952, psychoanalysts did not accept that a child would mourn or experience grief on separation but instead saw the child's distress as caused by elements of unconscious fantasies (in the film because the mother was pregnant).[7] Bowlby also incorporated Robertson's naturalistic observation methods of children's behaviors.[16]

- Melanie Klein during his psychoanalytic training. She was his supervisor; however, they had different views about the role of the mother in the treatment of a three-year-old boy. Specifically and importantly, Klein stressed the role of the child's fantasies about his mother,[19] but Bowlby emphasised the actual history of the relationship. Bowlby's views—that children were responding to real life events and not unconscious fantasies—were rejected by psychoanalysts, and Bowlby was effectively ostracised by the psychoanalytic community. He later expressed the view that his interest in real-life experiences and situations was "alien to the Kleinian outlook".[7] Furthermore, Bowlby explained in an interview with Milton Stenn in 1977 that the psychoanalytic community did not accept his developmental theories as they were completely different from the unconscious fantasy theories surrounding psychoanalysis during that time.[10] He further explained that:

There were certain groups who took to it with great enthusiasm, other groups were directly lukewarm and other hostile, each profession reacted differently. The social workers took to it with enthusiasm; the psychoanalysts treated it with caution, curiously and for me infuriatingly pediatricians were initially hostile but subsequently many of them became very supporting; adult psychiatrists totally uninterested, totally ignorant, totally uninterested.[20]

- Donald Winnicott, who was a pediatrician and child psychoanalyst, had an immense influence on Bowlby's work and career. Bowlby and Winnicott had several similarities within their professional work as they were the first to explain the importance of social interactions at an early age.[21] Both Bowlby and Winnicott argued that humans come into the world with a predisposition to be sensitive to social interactions and to need these interactions in order to have a healthy development.[21] However, although Bowlby and Winnicott's ideas were similar, they took vastly different approaches when dealing with their research.[10] For example, Bowlby was interested in how a child's environment is internalized and affects the child's development, while Winnicott was more interested in "the way the inner world engages with and thereby is affected by external events".[21]: 116 Despite their differences in approaching their research interests, Bowlby explained in an interview that his research for the World Health Organization influenced policies regarding child care; however, none of this would have been possible without the help of Winnicott.[10] Winnicott worked more at a clinical level than Bowlby which influenced several social workers as he spent his career working to change policies.[10] Bowlby explained that Winnicott is one of the more important individuals who was able to push Bowlby's work to change policies.[10]

Maternal deprivation

editIn 1949, Bowlby's earlier work on delinquent and affectionless children and the effects of hospitalised and institutionalised care led to his being commissioned to write the World Health Organization's report on the mental health of homeless children in post-war Europe.[16] The result was Maternal Care and Mental Health, published in 1951.[22]

Bowlby drew together such limited empirical evidence as existed at the time from across Europe and the US. His main conclusions, that "the infant and young child should experience a warm, intimate, and continuous relationship with his mother (or permanent mother substitute) in which both find satisfaction and enjoyment" and that not to do so may have significant and irreversible mental health consequences, were both controversial and influential. The 1951 WHO publication was highly influential in causing widespread changes in the practices and prevalence of institutional care for infants and children, and in changing practices relating to the visiting of infants and small children in hospitals by parents.[23][24][25] The theoretical basis was controversial in many ways. He broke with psychoanalytic theories which saw infants' internal life as being determined by fantasy rather than real life events. Some critics profoundly disagreed with the necessity for maternal (or equivalent) love to function normally,[26] or that the formation of an ongoing relationship with a child was an important part of parenting.[27] Others questioned the extent to which his hypothesis was supported by the evidence. There was criticism of the confusion of the effects of privation (no primary attachment figure) and deprivation (loss of the primary attachment figure) and in particular, a failure to distinguish between the effects of the lack of a primary attachment figure and the other forms of deprivation and understimulation that may affect children in institutions.[28]

The monograph was also used for political purposes to claim any separation from the mother was deleterious to discourage women from working and leaving their children in daycare by governments concerned about maximising employment for returned and returning servicemen.[28]

In 1962, WHO published Deprivation of maternal care: A Reassessment of its Effects to which Mary Ainsworth, Bowlby's close colleague, contributed with his approval, to present the recent research and developments and to address misapprehensions.[29] This publication also attempted to address the previous lack of evidence on the effects of paternal deprivation.

According to Rutter, the importance of Bowlby's initial writings on "maternal deprivation" lay in his emphasis that children's experiences of interpersonal relationships were crucial to their psychological development.[27]

Development of attachment theory

editIn his 1988 work A Secure Base, Bowlby explained that the data was not, at the time of the publication of Maternal Care and Mental Health, "accommodated by any theory then current and in the brief time of my employment by the World Health Organization there was no possibility of developing a new one". He then went on to describe the subsequent development of attachment theory.[30] Because he was dissatisfied with traditional theories, Bowlby sought new understanding from such fields as evolutionary biology, ethology, developmental psychology, cognitive science and control systems theory and drew upon them to formulate the innovative proposition that the mechanisms underlying an infant's tie emerged as a result of evolutionary pressure.[31] "Bowlby realised that he had to develop a new theory of motivation and behaviour control, built on up-to-date science rather than the outdated psychic energy model espoused by Freud."[16] Bowlby expressed himself as having made good the "deficiencies of the data and the lack of theory to link alleged cause and effect" in Maternal Care and Mental Health in his later work Attachment and Loss published in 1969.[32]

Ethology and evolutionary concepts

editFrom the 1950s, Bowlby was in contact with leading European ethologists, namely Niko Tinbergen, Konrad Lorenz, and Robert Hinde.[33] Bowlby was inspired by the study Lorenz conducted on goslings, showing that they imprint on the first animate object they see. Bowlby was encouraged by an evolutionary biologist, Julian Huxley, to look further into ethology to help further his research in psychoanalysis as he introduced Bowlby to the impactful work by Tinbergen on "The Study of Instinct".[34][33] Bowlby followed this guidance and became interested in ethology as he wanted to rewrite psychoanalysis in order to focus this research field around a concrete theory in which psychoanalysis was lacking.[34] He admired the methodological approach to ethology that psychoanalysis was not familiar with (Van der Horst, 2011). From reading widely in ethology, Bowlby was able to learn that ethologists supported the theoretical ideas through concrete empirical data.[34]

Using the viewpoints of this emerging science and reading extensively in the ethology literature, Bowlby developed new explanatory hypotheses for what is now known as human attachment behaviour. In particular, on the basis of ethological evidence he was able to reject the dominant Cupboard Love theory of attachment prevailing in psychoanalysis and learning theory of the 1940s and 1950s. He also introduced the concepts of environmentally stable or labile human behaviour allowing for the revolutionary combination of the idea of a species-specific genetic bias to become attached and the concept of individual differences in attachment security as environmentally labile strategies for adaptation to a specific childrearing niche. Alternatively, Bowlby's thinking about the nature and function of the caregiver-child relationship influenced ethological research, and inspired students of animal behaviour such as Tinbergen, Hinde, and Harry Harlow.

One of Harlow's students, Stephen Suomi, wrote about the contributions Bowlby's made to ethology,[35] including that Harlow brought attachment research into animal research specifically with rhesus monkeys and various other species of monkeys and apes.[36] Another contribution according to Suomi was that Bowlby influenced animal researchers to examine separation in animals. Furthermore, Suomi wrote that Bowlby brought to the field of ethology the acknowledgement of the consequences over time from different attachment styles that are prevalent in rhesus monkeys (specifically in the work of Harlow). According to Suomi, "Although Bowlby was a psychoanalyst by formal training, he was a true ethologist at heart".[36]

Van der Horst, Van der Veer, and Van IJzendoorn write:

Bowlby spurred Hinde to start his ground breaking work on attachment and separation in primates (monkeys and humans), and in general emphasized the importance of evolutionary thinking about human development that foreshadowed the new interdisciplinary approach of evolutionary psychology. Obviously, the encounter of ethology and attachment theory led to a genuine cross-fertilization.[33]: 322–323

"Attachment and Loss" trilogy

editBefore the publication of the trilogy in 1969, 1972 and 1980, the main tenets of attachment theory, building on concepts from ethology and developmental psychology, were presented to the British Psychoanalytical Society in London in three now classic papers: "The Nature of the Child's Tie to His Mother" (1958), "Separation Anxiety" (1959), and "Grief and Mourning in Infancy and Early Childhood" (1960). Bowlby rejected psychoanalytic explanations for attachment, and in return, psychoanalysts rejected his theory. At about the same time, Bowlby's former colleague Mary Ainsworth was completing extensive observational studies on the nature of infant attachments in Uganda with Bowlby's ethological theories in mind. Her results in this and other studies contributed greatly to the subsequent evidence base of attachment theory as presented in 1969 in Attachment, the first volume of the Attachment and Loss trilogy.[37] The second and third volumes, Separation: Anxiety and Anger and Loss: Sadness and Depression, followed in 1972 and 1980 respectively. Attachment was revised in 1982 to incorporate recent research.

According to attachment theory, attachment in infants is primarily a process of proximity seeking to an identified attachment figure in situations of perceived distress or alarm for the purpose of survival. Infants become attached to adults who are sensitive and responsive in social interactions with the infant, and who remain as consistent caregivers for some months during the period from about 6 months to two years of age. Parental responses lead to the development of patterns of attachment which in turn lead to "internal working models" which will guide the individual's feelings, thoughts, and expectations in later relationships.[38] More specifically, Bowlby explained in his three volume series on attachment (1973, 1980, & 1982) that all humans develop an internal working model of the self and an internal working model of others. The self-model and other-model are built off of early experiences with their primary caregiver and shape an individual's expectation on future interactions with others and interactions within interpersonal relationships. The self-model will determine how the individual sees themselves, which will impact their self-confidence, self-esteem, and dependency. The other-model will determine how an individual sees others, which will impact their avoidance or approach orientation, loneliness, isolation, and social interactions. In Bowlby's approach, the human infant is considered to have a need for a secure relationship with adult caregivers, without which normal social and emotional development will not occur.

As the toddler grows, it uses its attachment figure or figures as a "secure base" from which to explore. Mary Ainsworth used this feature in addition to "stranger wariness" and reunion behaviours, other features of attachment behaviour, to develop a research tool called the "strange situation" for developing and classifying different attachment styles.

The attachment process is not gender specific as infants will form attachments to any consistent caregiver who is sensitive and responsive in social interactions with the infant. The quality of the social engagement appears to be more influential than amount of time spent.[37]

Darwin biography

editBowlby's last work, published posthumously, is a biography of Charles Darwin, which discusses Darwin's "mysterious illness" and whether it was psychosomatic.[39] In this work, Bowlby explained that:

In order to obtain a clear understanding of the current relationships existing between members of any family it is usually illuminating to examine how the pattern of family relationships has evolved. That leads to a study of earlier generations, the calamities and other events that may have affected their lives and the patterns of family interaction that results. In the case of the family in which Darwin grew up, I believe such study to be amply rewarding. For that reason alone it would be necessary to start with his grandfathers' generation.[39]

Bowlby pointed out that Darwin suffered a curious denial about his mother's death, once writing in a condolence letter "never in my life having lost one near relation" and during a Scrabble-like game when another player added 'M' to 'OTHER', he stared long at the board then cried: 'There's no such word as M-OTHER'.[40]

Bowlby's legacy

editAlthough not without its critics, attachment theory has been described as the dominant approach to understanding early social development and it has given rise to a great surge of empirical research into the formation of children's close relationships.[41] As it is presently formulated and used for research purposes, Bowlby's attachment theory stresses the following important tenets:[42]

- Children between 6 and 30 months are very likely to form emotional attachments to familiar caregivers, especially if the adults are sensitive and responsive to child communications.

- The emotional attachments of young children are shown behaviourally in their preferences for particular familiar people; their tendency to seek proximity to those people, especially in times of distress; and their ability to use the familiar adults as a secure base from which to explore the environment.

- The formation of emotional attachments contributes to the foundation of later emotional and personality development, and the type of behaviour toward familiar adults shown by toddlers has some continuity with the social behaviours they will show later in life.

- Events that interfere with attachment, such as abrupt separation of the toddler from familiar people or the significant inability of carers to be sensitive, responsive or consistent in their interactions, have short-term and possible long-term negative impacts on the child's emotional and cognitive life.

A mountain in Kyrgyzstan has been named after Bowlby.[43]

See also

editSelected bibliography

edit- Bowlby J (1995) [1950]. Maternal Care and Mental Health. The master work series. Vol. 3 (2nd ed.). Northvale, NJ; London: Jason Aronson. pp. 355–533. ISBN 978-1-56821-757-4. OCLC 33105354. PMC 2554008. PMID 14821768. [Geneva, World Health Organization, Monograph series no. 3].

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Bowlby J (1976) [1965]. Fry M (abridged &) (ed.). Child Care and the Growth of Love (Report, World Health Organization, 1953 (above)). Pelican books. Ainsworth MD (2 add. ch.) (2nd ed.). London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-013458-2. OCLC 154150053. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- Bowlby J (1999) [1969]. Attachment. Attachment and Loss (vol. 1) (2nd ed.). New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-00543-8. LCCN 00266879. OCLC 232370549. NLM 8412414.

- Bowlby J (1973). Separation: Anxiety & Anger. Attachment and Loss (vol. 2); (International psycho-analytical library no.95). London: Hogarth Press. ISBN 0-7126-6621-4. OCLC 8353942.

- Bowlby J (1980). Loss: Sadness & Depression. Attachment and Loss (vol. 3); (International psycho-analytical library no.109). London: Hogarth Press. ISBN 0-465-04238-4. OCLC 59246032.

- Bowlby J (1988). A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development. Tavistock professional book. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-422-62230-3. OCLC 42913724.

- Bowlby J (1991). Charles Darwin: A New Life. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-30930-0.

- Bretherton I (September 1992). "The origins of attachment theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth". Developmental Psychology. 28 (5): 759–775. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.28.5.759. OCLC 1566542.

- Holmes J (1993). John Bowlby and Attachment Theory. Makers of modern psychotherapy. London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-07730-3. OCLC 27266442.

- Van Dijken S (1998). John Bowlby: His Early Life: A Biographical Journey into the Roots of Attachment Theory. London; New York: Free Association Books. ISBN 1-85343-393-4. OCLC 39982501.

- Van Dijken S; Van der Veer R; Van IJzendoorn MH; Kuipers HJ (Summer 1998). "Bowlby before Bowlby: The sources of an intellectual departure in psychoanalysis and psychology". Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences. 34 (3): 247–269. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6696(199822)34:3<247::AID-JHBS2>3.0.CO;2-N. hdl:1887/2335. PMID 9686465. Archived from the original on 17 December 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- Mayhew B (November 2006). "Between love and aggression: The politics of John Bowlby". History of the Human Sciences. 19 (4): 19–35. doi:10.1177/0952695106069666. S2CID 145458292.

- Van der Horst FCP; Van der Veer R; Van IJzendoorn, MH (2007). "John Bowlby and ethology: An annotated interview with Robert Hinde". Attachment & Human Development. 9 (4): 321–335. doi:10.1080/14616730601149809. PMID 17852051. S2CID 146211690.

- Van der Horst FCP; LeRoy HA; Van der Veer R (2008). ""When strangers meet": John Bowlby and Harry Harlow on attachment behavior". Integrative Psychological & Behavioral Science. 42 (4): 370–88. doi:10.1007/s12124-008-9079-2. PMID 18766423.

- Van der Horst FCP (2011). John Bowlby – From Psychoanalysis to Ethology. Unraveling the Roots of Attachment Theory. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-470-68364-4.

Notes

edit- ^ Haggbloom, Steven J.; Warnick, Renee; Warnick, Jason E.; Jones, Vinessa K.; Yarbrough, Gary L.; Russell, Tenea M.; Borecky, Chris M.; McGahhey, Reagan; Powell, John L. III; Beavers, Jamie; Monte, Emmanuelle (2002). "The 100 most eminent psychologists of the 20th century". Review of General Psychology. 6 (2): 139–152. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.586.1913. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.6.2.139. S2CID 145668721.

- ^ "Edward John Mostyn Bowlby". Munks Roll – Lives of the Fellows. IX. Royal College of Physicians: 49. 21 August 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ "Dr Edward John Bowlby". The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. 28 February 2017. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Van Dijken, S. (1998). John Bowlby: His Early Life: A Biographical Journey into the Roots of Attachment Theory. London: Free Association Books

- ^ Schwartz, Joseph (March 2007). "Keeping on Pushing: An Interview with Richard Bowlby". Attachment: New Directions in Psychotherapy and Relational Psychoanalysis. 1 (1). London: Karnac books. ISSN 1753-5980. OCLC 796028458.

- ^ Bowlby R, King P (2004). Fifty Years of Attachment Theory: Recollections of Donald Winnicott and John Bowlby. Karnac Books. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-85575-385-3.

- ^ a b c d Schwartz J (1999). Cassandra's Daughter: A History of Psychoanalysis. Viking/Allen Lane. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-670-88623-4.

- ^ Bowlby, J. (1951). Maternal Care and Mental Health. New York: Schocken.P.89.

- ^ Burke's Peerage (2003) volume 1, page 460.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Kanter, J. (2007). John Bowlby, Interview with Dr. Milton Senn. Beyond the Couch: The Online Journal of the American Association for Psychoanalysis in Clinical Social Work, Issue 2. Retrieved from: http://www.beyondthecouch.org/1207/bowlby_int.htm

- ^ Kanter, J. (2007). John Bowlby, Interview with Dr. Milton Senn. Beyond the Couch: The Online Journal of the American Association for Psychoanalysis in Clinical Social Work, Issue 2. Retrieved from: http://www.beyondthecouch.org/1207/bowlby_int.htm, page 02

- ^ a b c d e Bowlby, J. (1946). Forty-Four Juvenile Thieves: Their Character and Home-Life (2nd ed.). London: Bailliere, Tindall & Cox.

- ^ Davies, Hillary A.; The Use of Psychoanalytic Concepts in Therapy with Families; London (2010); Karnac Books

- ^ Mercer, J. (2006). 'Understanding attachment.' Westport, CT:Praeger.

- ^ Alsop-Shields, Linda; Mohay, Heather (July 2001). "John Bowlby and James Robertson: theorists, scientists and crusaders for improvements in the care of children in hospital". Journal of Advanced Nursing. 35 (1): 50–58. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01821.x. ISSN 0309-2402.

- ^ a b c d e Bretherton, I (1992). "The Origins of Attachment Theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth" (1992)". Developmental Psychology. 28 (5): 759–775. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.28.5.759.

- ^ Ainsworth, M. D, Blehar, M, Waters, E, & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation. Hillsdale NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

- ^ Robertson, Joyce; Robertson, James (1953). "A two year old goes to the hospital". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 46 (6): 425–427. doi:10.1037/e528272004-001. PMC 1918555. PMID 13074181.

- ^ Klein, Felix (1923), "Zur Theorie der Abelschen Funktionen", Gesammelte Mathematische Abhandlungen, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 388–474, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-61949-6_22 (inactive 1 November 2024), ISBN 978-3-642-61950-2

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Kanter, J. (2007). John Bowlby, Interview with Dr. Milton Senn. Beyond the Couch: The Online Journal of the American Association for Psychoanalysis in Clinical Social Work, Issue 2. Retrieved from: http://www.beyondthecouch.org/1207/bowlby_int.htm, page 13

- ^ a b c Issroff, J., Reeves, C., Hauptman, B. (2005). Donald Winnicott and John Bowlby: personal and professional perspectives. London: Karnac Books Ltd

- ^ Bowlby, J (1951) Maternal Care and Mental Health, World Health Organization

- ^ Bakker, Nelleke (2 January 2019). "In the interests of the child: psychiatry, adoption, and the emancipation of the single mother and her child – the case of the Netherlands (1945–1970)". Paedagogica Historica. 55 (1): 121–136. doi:10.1080/00309230.2018.1514414. ISSN 0030-9230. S2CID 79498039.

- ^ Berth, Felix (3 July 2021). "This house is not a home: residential care for babies and toddlers in the two Germanys during the Cold War". The History of the Family. 26 (3): 506–531. doi:10.1080/1081602X.2021.1943488. ISSN 1081-602X. S2CID 237374967.

- ^ Berth, Felix (20 July 2021). "Discovering Bowlby: infant homes and attachment theory in West Germany after the Second World War". Paedagogica Historica. 59 (4): 688–704. doi:10.1080/00309230.2021.1934705. ISSN 0030-9230. S2CID 242723665.

- ^ Wootton, B. (1962). "A Social Scientist's Approach to Maternal Deprivation." In Deprivation of Maternal Care: A Reassessment of its Effects. Geneva: World Health Organization, Public Health Papers, No. 14. pp. 255–266

- ^ a b Rutter, M (1995). "Clinical Implications of Attachment Concepts: Retrospect and Prospect". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 36 (4): 549–571. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb02314.x. PMID 7650083.

- ^ a b Rutter (1981) Maternal Deprivation Reassessed, Second edition, Harmondsworth, Penguin.

- ^ Ainsworth M et al.(1962 ) Deprivation of Maternal Care: A Reassessment of its Effects. Geneva: World Health Organization, Public Health Papers, No. 14.

- ^ Bowlby J (1988) "A Secure Base: Clinical Applications of Attachment Theory". Routledge. London. ISBN 0-415-00640-6 (pbk)

- ^ Cassidy J. (1999) "The Nature of a Childs Ties", in Handbook of Attachment. Eds. Cassidy J and Shaver PR. Guilford press.

- ^ "This Week's Citation Classic" (PDF). Current Comment. No. 50. 15 December 1986.

- ^ a b c Van der Horst FCP; Van der Veer R; Van IJzendoorn MH (2007). "John Bowlby and ethology: An annotated interview with Robert Hinde". Attachment & Human Development. 9 (4): 321–335. doi:10.1080/14616730601149809. PMID 17852051. S2CID 146211690.

- ^ a b c Van der Horst, F. C. P. (2011). John Bowlby- From Psychoanalysis to Ethology. Unraveling the Roots of Attachment Theory. United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- ^ Van der Horst FCP; LeRoy HA; Van der Veer R (2008). ""When strangers meet": John Bowlby and Harry Harlow on attachment behavior". Integrative Psychological & Behavioral Science. 42 (4): 370–88. doi:10.1007/s12124-008-9079-2. PMID 18766423.

- ^ a b Suomi, S. J. (1995). Influence of attachment theory on ethological studies of biobehavioral development in nonhuman primates. In S. Goldberg, R. Muir, and J. Kerr (eds), Attachment Theory: Social, Developmental, and Clinical Perspectives (pp. 185–201). Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press.

- ^ a b Bowlby J (1999) [1969]. Attachment, 2nd edition, Attachment and Loss (vol. 1), New York: Basic Books. LCCN 00266879; NLM 8412414. ISBN 0-465-00543-8 (pbk). OCLC 232370549

- ^ Bretherton, I. and Munholland, K., A. Internal Working Models in Attachment Relationships: A Construct Revisited. Handbook of Attachment:Theory, Research and Clinical Applications 1999eds Cassidy, J. and Shaver, P., R. Guilford press ISBN 1-57230-087-6

- ^ a b Bowlby, J. (1991). Charles Darwin: A New Life. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-30930-0.

- ^ Holmes, Jeremy (2014). John Bowlby and attachment theory. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-87977-2.

- ^ Schaffer R. Introducing Child Psychology. 2007. Blackwell.

- ^ Mercer, J. (2006). Understanding Attachment. Westport, CT: Praeger.

- ^ "Mt. John Bowlby & Peak Mary Ainsworth". psychology.sunysb.edu. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

External links

edit- John Bowlby: Attachment Theory Across Generations 4-minute clip from a documentary film used primarily in higher education

- John Bowlby – Rediscovering a systems scientist Archived 19 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine A research report by the International Society for the Systems Sciences authored by Gary Metcalf in 2010

- The John Bowlby Centre for Psychotherapy Training