Eat a Peach is the third studio album and the first double album by American rock band the Allman Brothers Band. Produced by Tom Dowd, the album was released on February 12, 1972, in the United States by Capricorn Records. It was the band's fourth album since their debut The Allman Brothers Band in 1969; released as a double album, it constitutes both their third studio album and second live album, containing a mix of live and studio recordings released in 1972. Following their artistic and commercial breakthrough with the July 1971 release of the live album At Fillmore East, the Allman Brothers Band got to work on their third studio album. Drug use among the band became an increasing problem, and at least one member underwent rehab for heroin addiction. On October 29, 1971, lead and slide guitarist Duane Allman, group leader and founder, was killed in a motorcycle accident in the band's adopted hometown of Macon, Georgia, making it the final album to feature him.

| Eat a Peach | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album / Live album by | ||||

| Released | February 12, 1972 | |||

| Recorded |

| |||

| Venue | Fillmore East (New York City) | |||

| Studio | Criteria (Miami) | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 68:42 | |||

| Label | Capricorn | |||

| Producer | Tom Dowd | |||

| The Allman Brothers Band chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Eat a Peach | ||||

| ||||

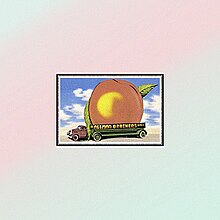

Eat a Peach contains studio recordings from September–December 1971 at Criteria Studios, Miami—both with and without Duane Allman—and live recordings from the band's famed 1971 Fillmore East performances. The album contains the extended half-hour-long "Mountain Jam", which was long enough to take up two full sides of the original double-LP. Other highlights include vocalist Gregg Allman's performance of his brother's favorite song, "Melissa", plus Dickey Betts' "Blue Sky", which went on to become a classic rock radio staple. The album artwork was created by W. David Powell and J. F. Holmes at Wonder Graphics, and depicts the band's name on a peach truck, in addition to a large gatefold mural of mushrooms and fairies. The album's title came from a quote by Duane Allman: "You can't help the revolution, because there's just evolution ... Every time I'm in Georgia, I eat a peach for peace".[1]

On release Eat a Peach was an immediate commercial success and peaked at number four on Billboard's Top 200 Pop Albums chart. The album was later certified platinum and remains a top seller in the band's discography.

Background

editThe Allman Brothers Band had struggled to achieve commercial success in their two and a half years on the touring circuit; their first two studio albums, The Allman Brothers Band (1969) and Idlewild South (1970), had debuted to only modest sales. Despite this, they had achieved significant acclaim due to their live performances, which included extended jam renditions of songs. The band's third release was a live album, titled At Fillmore East, and represented their artistic and commercial breakthrough: it immediately received solid sales upon its July 1971 release and went gold some months later. In about a "three-or-four-week period", the band quite literally went from "rags to riches", and were able to pay their debts to manager Phil Walden and record label Capricorn Records.[2]

Although suddenly wealthy and successful, much of the band and its entourage now struggled with substance abuse, which included instances of heroin addiction. Four individuals—group leader Duane Allman, bassist Berry Oakley, and roadies Robert Payne and Joseph "Red Dog" Campbell—checked into the Linwood-Bryant Hospital for rehabilitation in October 1971.[3] Their addictions had begun to affect their performances and matters seemed to only be getting worse, according to many involved.[4] The clinic was deemed a "joke" and a "nuthouse" by Payne and Red Dog, and was later described as more of a psychiatric ward, as true rehabilitation clinics were several years away.[5] All involved (including Duane) struggled to keep off the substance in the ensuing days.[6] Despite his struggles, Duane fueled the band's passion to get better and end their addictions: "Duane was so happy and full of positive energy. He was always like that unless he was just totally wasted. He was the leader, the great soul, and he kept saying, 'We are on a mission and it's time for this thing to happen,'" said Linda Oakley. "He was moving forward, and that energized everyone else. Everyone fed off of that."[7]

On October 29, 1971, Duane Allman, aged 24, was killed in a motorcycle accident a day after returning to the band's home of Macon, Georgia from an extended tour of concert gigs. Allman was exceeding a safe speed at the intersection of Hillcrest Avenue and Bartlett Street as a flatbed lumber crane approached.[8] The flatbed truck stopped suddenly in the intersection, forcing Allman to swerve his Harley-Davidson Sportster motorcycle sharply to the left to avoid a collision. As he was doing so, he struck either the back of the truck or the ball on the lumber crane and was immediately thrown from the motorcycle.[8] The motorcycle bounced into the air, landed on Allman and skidded another 90 feet (27 m) with him pinned underneath, crushing several internal organs. Though he was alive when he arrived at the hospital, despite immediate emergency surgery he died several hours later from massive internal injuries. The loss devastated all who knew him, just as At Fillmore East climbed into the top 15 of the national album charts.[9]

Recording and production

editWe thought about quitting because how could we go on without Duane? But then we realized: how could we stop?

Drummer Butch Trucks[10]

Several weeks before the gold certification of At Fillmore East and their rehabilitation, the band headed to Miami's Criteria Studios to work on their third studio album. Once again they'd be working with producer Tom Dowd, whom had been instrumental in the successful recording and production of At Fillmore East. The band laid down the initial tracks for "Blue Sky".[11] The band saved money on studio time by writing and debuting songs on the road.[11] The band worked on three songs: "Blue Sky", an instrumental titled "The Road to Calico" (which would eventually develop into "Stand Back", with added vocals) and "Little Martha", the only song solely credited to Duane Allman.[12] The band laid down these three songs and went back on the road for a short run of shows, and at this point several checked into rehab.[3] After Duane's death, the band held a meeting on their future; it was clear all wanted to continue, and after a short period, they returned to the road.[13] Drummer Butch Trucks later said, "We all had this thing in us and Duane put it there. He was the teacher and he gave something to us—his disciples—that we had to play out."[10]

Following Duane's death, which severely impacted younger brother, organist/lead vocalist/songwriter Gregg Allman, lead guitarist Dickey Betts gradually took over as group leader.[13] The band returned to Miami in December to complete work on the album.[14] Twiggs Lyndon, the band's former head roadie, joined them; he had just completed a stay in a psychiatric hospital stemming from his 1970 arrest for the murder of a concert promoter at one of the band's shows. Lyndon became the band's production manager.[14] The band recorded three more tracks with Dowd, including "Melissa", "Les Brers in A Minor", and "Ain't Wastin' Time No More".[14] Allman's death provided the band with motivation: "We were all putting more into it, trying so hard to make it as good as it would have been with Duane. We knew our driving force, our soul, the guy that set us all on fire, wasn't there and we had to do something for him," said Trucks.[15] The heroin addictions had taken their toll on the band members; Gregg Allman later said, "We were taking vitamins, we had doctors coming over and sticking us in the ass with B12 shots every day. Little by little by little, we crawled back up to the point where we were standing erect."[16]

The other material on Eat a Peach comes from live recordings. Dowd later said, "When we recorded At Fillmore East, we ended up with almost a whole other album's worth of good material, and we used [two] tracks on Eat a Peach. Again, there was no overdubbing".[17] Dowd started the mixing process for Eat a Peach but had run overtime and was called to commitments with Crosby, Stills and Nash; longtime Allman friend and colleague Johnny Sandlin took over for the remaining mixes.[18] Sandlin later said of the mixing process, "As I mixed songs like "Blue Sky," I knew, of course, that I was listening to the last things that Duane ever played and there was just such a mix of beauty and sadness, knowing there's not going to be any more from him".[18] He was particularly proud of his mixing work on the album, but was angry because he did not receive credit, only a "special thanks".[18]

Completing the recording of Eat a Peach raised each members' spirits. Said Allman, "The music brought life back to us all, and it was simultaneously realized by every one of us. We found strength, vitality, newness, reason, and belonging as we worked on finishing Eat a Peach".[19] "Those last three songs ... just kinda floated right on out of us ... The music was still good, it was still rich, and it still had that energy—it was still the Allman Brothers Band."[19]

Composition

editMuch of the music on Eat a Peach that was recorded after Duane's death directly dealt with the tragedy.[14] "Ain't Wastin' Time No More" was written by Gregg Allman for his brother immediately following his death.[14] The song was composed when Duane was still alive, on a 110-year-old Steinway piano in Studio D of Criteria,[16] but the lyrics deal with his passing, as well as veterans coming home from the Vietnam War.[19] The song relates to the theme that "death is an inescapable inevitability—that every day is precious."[20] "Les Brers in A Minor" is an instrumental written by Dickey Betts, and its title is "bad French" for "less brothers".[14] When rehearsing the song, all in the band felt something was familiar about it—which turned out to be a solo of Betts's from live renditions of "Whipping Post" that resurfaced many years later on a bootleg recording.[15] Recording of "Les Brers" began in the newly constructed Studio C of the recording complex at Criteria, but the band disliked the sound captured in the room and moved to Studio A. As a result, the recording contains a slight pitch variation due to the difficulty of matching the original speed of the instruments when the intro was spliced onto the master tape.[20]

Gregg Allman recorded "Melissa" primarily as a tribute to his brother, who adored the song; the song was written in 1967 while staying in a hotel in Pensacola, Florida, and was one of the first he saved after dozens of writing attempts.[15] Allman had previously not shown it to other members of the band ("I thought it was too soft for the Allman Brothers," he said), and was saving it for a possible solo album he assumed he would one day record.[15] "One Way Out" was recorded on June 27, 1971, the final night of concerts at the Fillmore East, which the band, a favorite of the famed venue's promoter Bill Graham, headlined; "Trouble No More" and "Mountain Jam" were culled from the band's March performances there.[15] "Mountain Jam" was always intended for inclusion on the band's next album; the band teased its appearance by including the opening seconds on the fade-out of the final song on At Fillmore East.[17] The band considered it a signature song of the group, but they deemed the performance that was recorded relatively mediocre.[17]

Artwork and title

editThe album's artwork was created by W. David Powell at Wonder Graphics. He had seen old postcards at a drugstore in Athens, Georgia, one depicting a peach on a truck and a watermelon on a rail car.[18] Believing them perfect for an Allman Brothers album, he purchased them and "bought cans of pink and baby-blue Krylon spray paint and created a matted area to make the cards on a twelve-by-twenty-four LP cover."[18] He envisioned the album having "an early-morning-sky feel". He hand-lettered the band name and photographed it with a small Kodak camera, developing the photos at the drugstore. He then cut and pasted the letters on the side of the truck, underneath the peach.[18]

The album includes an elaborate gatefold mural featuring a fantasy landscape of mushrooms (referencing the psychedelic drug, a band favorite in its early days) and fairies, drawn by Powell and J. F. Holmes. There was very little planning involved in the piece, which was created when the duo were in Vero Beach, Florida.[21] When one would be drawing or painting the image, another would be swimming in the ocean. "We swapped off this way with virtually no conversation about the drawing, just fluid trade-offs," said Powell.[21] The art was created on a large illustration board, "on a one-to-one scale—it was the size of the actual spread," according to Powell.[21] Holmes' work is featured largely on the left, with Powell's on the right. Both were "profoundly influenced" by Early Netherlandish painter Hieronymous Bosch on the piece.[21]

At the time the artwork was finalized, Duane Allman was still alive and the title had not been finalized.[18] As a result, the album lacks a title on the cover, which was an unusual approach for bands at the time. Powell later said, "When we showed it to someone at the label, he said, 'They are so hot right now, we could sell it in a brown paper bag'".[22] Atlantic initially intended to title the album The Kind We Grow in Dixie, the label of the postcard series Powell had seen in Athens,[18] but the band refused. Trucks suggested they name the album Eat a Peach for Peace, after a quote from Duane Allman. When the writer Ellen Mandel asked him what he was doing to help the revolution, he replied:

I'm hitting a lick for peace—and every time I'm in Georgia, I eat a peach for peace. But you can't help the revolution, because there's just evolution. I understand the need for a lot of changes in the country, but I believe that as soon as everybody can just see a little bit better, and get a little hipper to what's going on, they're going to change it. Everybody will—not just the young people. Everybody is going to say, 'Man, this stinks. I cannot tolerate the smell of this thing anymore. Let's eliminate it and get straight with ourselves.' I believe if everybody does it for themselves, it'll take care of itself.[23][22]

Drummer Butch Trucks considered Allman's comment a sly reference to the poem "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" by T. S. Eliot, one of Allman's favorite poets.[22] An untrue story persisted for many years after the album's release that it was named after the truck Allman crashed into, purported to be a peach truck.[24] The album art was later selected by Rolling Stone magazine in 1991 as one of the 100 greatest album covers of all time.[25]

Release

edit| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | [26] |

| Christgau's Record Guide | B[27] |

| The Encyclopedia of Popular Music | [28] |

| Rolling Stone Album Guide | [29] |

Before the release of Eat a Peach, industry talk suggested the demise of the group after the death of Duane Allman.[21] The record's promotional campaign was coordinated by Dick Wooley, the former head of promotion for Atlantic Records. He had recently quit his position there and was contacted by Walden to help Capricorn in its efforts.[21] (Capricorn Records had recently separated from Atlantic Records as well; Eat a Peach would be among the first Capricorn albums released under a new distribution deal with Warner Bros. Records.) "They needed help because the buzz in the record business and on the street was that the ABB was finished as a band and would never survive without Duane," said Wooley.[21] After being played some songs from Eat a Peach by Sandlin, Wooley was "blown away" and accepted the offer at half his usual salary.[21] He arranged to have the band's New Year's Eve performance at New Orleans' Warehouse live simulcast on radio. "I took a gamble and cobbled together a network of radio stations in the Southeast via Ma Bell phone lines," said Wooley.[30] The stunt helped launch Eat a Peach, which was issued by Capricorn in February 1972 and became an instant success.[21] The album shipped enough copies to be certified by the RIAA as gold and peaked at number four on Billboard's Top 200 Pop Albums chart. "We'd been through hell, but somehow we were rolling bigger than ever," said Gregg Allman.[31]

Rolling Stone's Tony Glover wrote that, even without their leader, "the Allman Brothers are still the best goddamned band in the land ... I hope the band keeps playing forever—how many groups can you think of who really make you believe they're playing for the joy of it?"[32] In Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies (1981), Robert Christgau called side three "a magnificent testament", but was relatively unimpressed by the rest of the album, especially the low-tempo "Mountain Jam" sides: "I know the pace of living is slow down there, but this verges on the comatose. And all the tape in the world isn't going to bring Duane back."[27] In a retrospective review, Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic called the record a showcase of "the Allmans at their peak".[26] David Quantick of BBC Music also considered it their "creative peak", praising the album's "well-played, surprisingly lean bluesy rock".[33] The album is mentioned as the band's top studio recording in the 2008 book 1,000 Recordings to Hear Before You Die (2008), with author Tom Moon praising the record's "sedate, beautifully contemplative studio material".[34]

"Melissa" was the album's most successful single, peaking at number 65 on the Billboard Hot 100. "Ain't Wastin' Time No More" and "One Way Out" were also singles, charting at numbers 77 and 86, respectively.[35]

Touring

editBiographer Alan Paul notes that the band's members "all profoundly felt the absence of their guiding light" during the touring cycle for Eat a Peach.[30] Dickey Betts had to convince the band members to tour, since all other members were reluctant.[30] Despite rumors, the band did not replace Duane Allman, and simply toured as a five-piece.[36] The Allman Brothers Band played 90 shows in 1972 in support of the record. "We were playing for him and that was the way to be closest to him," said Trucks.[30] Allman and Oakley took turns introducing songs, which was traditionally Duane's role.[36] Betts learned Duane's slide guitar parts, but put his own spin on them.[36] Oakley had a downward spiral following Duane's death and was significantly inebriated for many shows on the tour. "He wasn't playing like he used to—instead, he'd hit maybe every fifth note," recalled Allman.[37] Occasionally, the band would have bassist Joe Dan Petty, later of Grinderswitch, cover for Oakley for the show.[37] After nearly a year of severe depression, Oakley was killed in a motorcycle accident not dissimilar from his friend's in November 1972.

Many label mates on Capricorn opened for the band, including Wet Willie, Cowboy, and Dr. John.[38]

Track listing

edit| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Ain't Wastin' Time No More" | Gregg Allman | 3:40 |

| 2. | "Les Brers in A Minor" | Dickey Betts | 9:03 |

| 3. | "Melissa" | G. Allman | 3:05 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Mountain Jam" (live) |

| 19:37 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "One Way Out" (live) | 4:58 | |

| 2. | "Trouble No More" (live) | Muddy Waters | 3:28 |

| 3. | "Stand Back" |

| 3:25 |

| 4. | "Blue Sky" | Betts | 5:10 |

| 5. | "Little Martha" | D. Allman | 2:08 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Mountain Jam" (live – continued) |

| 15:06 |

Notes

- "Mountain Jam", "One Way Out" and "Trouble No More" recorded live at the Fillmore East:

- "Mountain Jam" – March 13, 1971 (late show)

- "Trouble No More" – March 13, 1971 (early show)

- "One Way Out" – June 27, 1971

- All compact disc editions of the album include the entirety of "Mountain Jam" (which runs 33:44) as track 4.

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Statesboro Blues" | Blind Willie McTell | 4:25 |

| 2. | "Don't Keep Me Wonderin'" | G. Allman | 3:46 |

| 3. | "Done Somebody Wrong" |

| 3:38 |

| 4. | "One Way Out" |

| 5:08 |

| 5. | "In Memory of Elizabeth Reed" | Betts | 12:50 |

| 6. | "Midnight Rider" |

| 3:08 |

| 7. | "Hot 'Lanta" |

| 5:51 |

| 8. | "Whipping Post" | G. Allman | 20:06 |

| 9. | "You Don't Love Me" | Willie Cobbs | 17:24 |

Personnel

editAll credits adapted from liner notes.[39]

|

The Allman Brothers Band

Additional Musicians

|

Production

|

Charts

edit| Chart (1972) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australian Albums (Kent Music Report)[40] | 35 |

| Canada Top Albums/CDs (RPM)[41] | 12 |

| US Billboard 200[42] | 4 |

Certifications

edit| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| United States (RIAA)[43] | Platinum | 1,000,000^ |

|

^ Shipments figures based on certification alone. | ||

Notes

edit- ^ Allman, Galadrielle (2014). Please Be with Me: A Song for My Father. Spiegel & Grau. p. 343. ISBN 978-1-4000-6894-4.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 143.

- ^ a b Paul 2014, p. 147.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 149.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 151.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 153.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 155.

- ^ a b Paul 2014, p. 156.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 160.

- ^ a b Paul 2014, p. 165.

- ^ a b Paul 2014, p. 144.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 145.

- ^ a b Paul 2014, p. 162.

- ^ a b c d e f Paul 2014, p. 167.

- ^ a b c d e Paul 2014, p. 168.

- ^ a b Allman & Light 2012, p. 203.

- ^ a b c Paul 2014, p. 169.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Paul 2014, p. 170.

- ^ a b c Allman & Light 2012, p. 204.

- ^ a b Poe 2008, p. 218.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Paul 2014, p. 172.

- ^ a b c Paul 2014, p. 171.

- ^ Poe 2008, p. 219.

- ^ "Hidden Messages: Allman Brothers Eat a Peach". Snopes.com. April 26, 2007. Retrieved July 11, 2014.

- ^ Freeman, Scott (June 2003). "A Music Album". Atlanta. Atlanta: Emmis Publishing: 93. Retrieved July 11, 2014.

- ^ a b Stephen Thomas Erlewine. "Review: Eat a Peach". AllMusic. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ^ a b Christgau, Robert (1981). "The Allman Brothers Band: Eat a Peach". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306804093.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2007). The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195313734.

- ^ Coleman, Mark; Skanse, Richard (2004). Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). New York: Fireside Books. pp. 14–16. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- ^ a b c d Paul 2014, p. 173.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 210.

- ^ Tony Glover (April 13, 1972). "Reviews: Eat a Peach". Rolling Stone. New York City: Straight Arrow Publishers, Inc. ISSN 0035-791X. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ^ David Quantick (2011). "The Allman Brothers Band Eat a Peach Review". BBC Music. Retrieved July 11, 2014.

- ^ Moon, Tom (2008). 1,000 Recordings To Hear Before You Die. Workman Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-7611-3963-8. pp. 16–17.

- ^ "The Allman Brothers Band – Chart History: Hot 100". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ a b c Paul 2014, p. 174.

- ^ a b Allman & Light 2012, p. 208.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 212.

- ^ Eat a Peach (liner notes). The Allman Brothers Band. US: Capricorn. 1972. CPN-2-0102.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. p. 15. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ^ "Top RPM Albums: Issue 7711". RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ "The Allman Brothers Band Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ "American album certifications – Allman Brothers". Recording Industry Association of America.

References

edit- Paul, Alan (2014). One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1-250-04049-7.

- Freeman, Scott (1996). Midnight Riders: The Story of the Allman Brothers Band. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-29452-2.

- Poe, Randy (2008). Skydog: The Duane Allman Story. Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-939-8.

- Allman, Gregg; Light, Alan (2012). My Cross to Bear. William Morrow. ISBN 978-0-06-211203-3.

Further reading

edit- Draper, Jason (2008). A Brief History of Album Covers. London: Flame Tree Publishing. pp. 106–107. ISBN 9781847862112. OCLC 227198538.