David Keith Lynch (born January 20, 1946) is an American filmmaker, painter, television director, visual artist, musician and occasional actor. Known for his surrealist films, he has developed his own unique cinematic style,[1] most often noted for its dreamlike imagery and meticulous sound design. The surreal and, in many cases, violent elements in his films have earned them a reputation as works that "disturb, offend or mystify" general audiences.[2]

David Keith Lynch | |

|---|---|

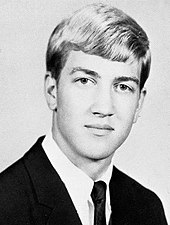

Lynch's high school senior portrait, 1964 | |

| Born | David Keith Lynch January 20, 1946 Missoula, Montana, U.S. |

| Alma mater | American Film Institute Conservatory |

| Occupation | Filmmaker |

| Years active | 1966–present |

Although born in Missoula, Montana, Lynch spent his youth traveling across the United States due to his father Donald's job for the Department of Agriculture; as a result, Lynch attended school across several states. Raised in a contented, happy family, the young Lynch was a member of the Boy Scouts of America, reaching the highest rank of Eagle Scout. However, Lynch took to building fireworks and playing the bongos in a Beat Generation nightclub as acts of rebellion, before discovering that he could translate his childhood fascination with drawing and painting into a career in fine art. Lynch and his close friend Jack Fisk travelled to Austria hoping to study under Oskar Kokoschka, but the artist was not present at the time.

Returning to the United States, Lynch enrolled in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. Although initially focusing on oil painting and sculpture, Lynch found himself beginning to experiment with short films. After completing several short animated and partly animated works, Lynch was prompted by his mentor Bushnell Keeler to apply for one of four annual grants from the American Film Institute to fund another film project. The resulting film, The Grandmother, paved the way for Lynch's scholarship at the AFI Conservatory; while studying there, Lynch wrote and directed a film which would take several years to gestate—his feature-length début and the beginning of his commercial film career, Eraserhead.

Birth and childhood

editLynch was born on January 20, 1946, in Missoula, Montana to Donald and Edwina "Sunny" (née Sundholm) Lynch,[3][4] who met as students at Duke University.[5] David was the eldest of three siblings. For the most part a housewife, Sunny also tutored English lessons, having earned her degree at Duke.[4] Donald Lynch worked for the United States Department of Agriculture, which necessitated moving the family around the country—they relocated to Sandpoint, Idaho, when David was two months old. Before his fourteenth birthday the family had lived in Spokane, Washington; Durham, North Carolina; Boise, Idaho; and Alexandria, Virginia.[6] The young Lynch easily coped with this transitory lifestyle,[7] and was popular throughout his school years,[8] having found it easy for an "outsider" such as himself to make friends after moving to a new school.[9] Lynch's elementary and junior high school educations were taken in Boise; he attended high school in Alexandria.[4]

Lynch recalls having a happy childhood, although he suffered from bouts of agoraphobia in his youth, especially after having been scared by a screening of Henry King's 1952 film Wait till the Sun Shines, Nellie, when he was six years old. He would develop a brief habit of wearing three neckties at a time, which he understands to have been a manifestation of his personal insecurity.[10] He also points to a particular image from his childhood that shaped his understanding of the world—"[my youth] was a dream world, those droning airplanes, blue skies, picket fences, green grass, cherry trees. Middle America as it was supposed to be. But then on the cherry tree would be this pitch oozing out, some of it black, some of it yellow, and there were millions and millions of red ants racing all over the sticky pitch, all over the tree. So you see, there's this beautiful world and you just look a little bit closer and it's all red ants".[11]

Finding the calm and contented nature of his home life frustrating, the young Lynch sought ways to secretly rebel against his parents. He and a friend took to building bottle rockets; after a particularly powerful rocket severely damaged his friend's foot they switched their focus to making and detonating pipe bombs for fun instead. A large pipe bomb which they detonated in a school swimming pool was heard by several neighbors, and resulted in Lynch and his friend being arrested.[12] Lynch was also a member of the high school fraternity Alpha Omega Upsilon, and learned to play the bongos while frequenting a nightclub popular with the Beat Generation, earning the nickname "Bongo Dave".[13]

Lynch was a member of the Boy Scouts of America, attaining the rank of Eagle Scout. His childhood friend Toby Keeler posited that this experience and the "be prepared" Scout motto formed the basis of Lynch's "do it yourself" approach to filmmaking and art, and shaped his ability to "make things out of nothing".[7] Lynch had initially joined the Scouts in order to "put it behind" him, but continued at the urging of his father; he eventually summed up his biography as "Eagle Scout. Missoula, Montana" in a 1990 press release for Wild at Heart. As a Boy Scout, Lynch was present at John F. Kennedy's presidential inauguration,[8] which took place on Lynch's 15th birthday.[14] When Kennedy was assassinated in 1963, Lynch was the first in his school to hear of it, as he was working on a display case rather than attending class.[15]

Art student

editLynch's interest in art began at an early age; he recalled his father bringing home large amounts of paper from his government job, and because his mother would not let him use coloring books, he would draw and paint on this spare paper. Lynch's early artwork mostly depicted war-related imagery—weaponry and fighter planes—based on his collection of toy military equipment. He frequently depicted the M1917 Browning machine gun, calling it a favorite of his.[16] Later in life, however, Lynch was summoned for conscription for the Vietnam War, and declared 4-F, "unfit for military service"[17] (spasms of the intestines and a dislocated vertebrae[18]).

At the age of 14, Lynch's family visited Hungry Horse, Montana, staying with his aunt and uncle near Hungry Horse Dam. Their next-door neighbor was an artist named Ace Powell, whose style was similar to that of Charlie Russell and Frederic Remington. Powell and his wife were both painters, and would let Lynch work with their materials while he was staying in town; however, Lynch found it difficult to believe that art was something in which he could forge a career, believing it to be a hobby peculiar to the Western United States.[16] Returning home to Virginia, Lynch met Keeler's father Bushnell, who was also an artist. Lynch rented space in the elder Keeler's studio and, alongside his friend Jack Fisk, worked on his art until he had finished school. From there, he enrolled in the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, but soon dropped out.[8]

Bushnell Keeler has commented that Lynch's dropping out of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston "worked to his detriment then, but may now be one of his greatest assets". Keeler recounts that Lynch left the school after allowing one of his tutors to use his dormitory room; the tutor, who was in the process of divorcing his wife, spent several nights in Lynch's room with his mistress, while Lynch obligingly slept on the floor. Rather than confronting the tutor about this situation, Lynch felt it would be easier to leave school instead.[19] Keeler and film critic Greg Olson posit that this desire to avoid confrontation has shaped the characters he has written, who often seek an "escape route" in the face of adversity rather than face it directly. Olson has further added that several of Lynch's later works—Dune and Twin Peaks—would have "been less compromised" had Lynch been of a more adversarial personality; as they were, both projects featured interference from film and television studios respectively.[20]

After this, Lynch and Fisk planned a three-year trip to Austria, planning to study under the expressionist painter Oskar Kokoschka, who was one of Lynch's "least favorite painters".[19] However, when Lynch arrived in Salzburg, he found that the artist had left, prompting him to return to America. Before leaving Europe, the pair travelled to Athens by train, to visit Lynch's girlfriend at the time, who was holidaying there. However, when they arrived in Greece they discovered that she had already left for home; Lynch and Fisk departed for America shortly thereafter.[21] Upon his return, Lynch enrolled in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, devoting himself to painting and sculpture.[8] Lynch's paintings, which were influenced by the works of Francis Bacon,[22] were executed in oils, and following an incident in which a moth landed in a still-drying piece, he began embedding insects in his work.[23]

Life in Philadelphia was disturbing for Lynch, who had by this point married his pregnant girlfriend Peggy Reavey. The two had met in 1964, and wed in 1967, shortly before the birth of their daughter Jennifer.[23]

Lynch and his family spent five years living in an atmosphere of "violence, hate and filth".[24] The area was rife with crime, which would later inform the tone of his work. Describing this period of his life, Lynch said "I saw so many things in Philadelphia I couldn't believe ... I saw a grown woman grab her breasts and speak like a baby, complaining her nipples hurt. This kind of thing will set you back".[25] In Olson's David Lynch: Beautiful Dark, the author posits that this time contrasted starkly with the director's childhood in the Pacific Northwest, giving the director a "bipolar, Heaven-and-Hell vision of America" which has subsequently shaped his films.[24]

Short films

editLynch's experiments with moving sculptures led to his interest in the medium of motion picture film.[26] In 1966, with the help of Fisk, Lynch animated a one-minute short feature called Six Figures Getting Sick; the project cost $200 and was filmed with a sixteen millimeter camera.[23] The sculpture-motion picture was a simple animated loop of several figures growing increasingly nauseous before vomiting down the screen. This loop was repeated several times and accompanied by the sound of an air-raid siren; however, it was projected onto a cast of Lynch's head in order to distort the footage further.[27]

After Six Figures Getting Sick was completed, one of Lynch's classmates, H. Barton Wasserman, offered to pay $1000 for a similar motion picture to be made for an art installation in his home. Lynch purchased a clockwork Bolex movie camera, and began to teach himself cinematography. Lynch worked on the commissioned motion picture over the next two months, crafting a mix of live action and animation in a split-screen format. However, when the film was developed, an error along the way had rendered it indistinguishable and unusable. Wasserman allowed Lynch to keep the remainder of the budget, which he used to fund the production of a new motion picture project, The Alphabet.[28]

Similarly to Wasserman's unfinished commission, 1968's The Alphabet was composed of both live action and animation. The abstract 16mm movie was inspired by an experience related by Lynch's wife Peggy, who had once seen her niece reciting the alphabet in her sleep while suffering from a nightmare. Peggy was the sole live action actor in the film, which depicted in animation the nightmares of a young girl. The film displays several elements that would continue throughout Lynch's oeuvre, including the use of meticulous sound design to convey unease. The sound of his infant daughter crying was recorded on a faulty cassette recorder and included in the film's soundtrack; the malfunctioning of the recorder not only lent the sound a desirably distorted quality but allowed Lynch to return it to where he had purchased it from upon finishing the film.[28]

Although Lynch was enthusiastic about the medium of film, he realized that the wages from his job as a printer would not stretch to cover future budgetary needs. Bushnell Keeler recommended that Lynch apply for a grant from the newly formed American Film Institute (AFI). Together with a copy of The Alphabet, Lynch's application included an eight-page treatment for a project titled The Grandmother. The submission was successful, and Lynch was awarded one of four annual grants from the AFI,[29] totalling $5,000.[23] The Grandmother was filmed in Lynch's home in Philadelphia and starred his friends and colleagues. Lynch's initial grant of $5,000 was later supplemented by a further $2,200 also supplied by the AFI.[30] Completed in 1970, it relates the story of a family grown from the ground like plants; the neglected and abused son seeks to create stability in his life by growing a grandmother from a seed.[31] Once again, the film mixes animation with live action footage, and features the use of both pallid stage make-up reminiscent of the silent film era, and a similarly washed-out use of colour to The Alphabet.[32] Running for thirty minutes, the film has been described by critics Colin Odell and Michelle Le Blanc as "fall[ing] into that twilight category of film that is too short to be a feature and too long to be a short film".[33]

AFI Conservatory

editHaving completed The Grandmother, Lynch realized that filmmaking was the career he wanted to pursue. He accepted a scholarship at the AFI Conservatory,[34] Lynch moved to Los Angeles, California, with his family, and recalls having felt "the evaporation of fear" after leaving the crime and poverty of Philadelphia.[35] Lynch was dissatisfied with the Conservatory and considered dropping out, but he changed his mind after being offered the chance to produce a script of his own devising. He was given permission to use the school's full campus for film sets; he converted the school's disused stables into a series of sets and lived there.[34] He began work on a script titled Gardenback, based on his painting of a hunched figure with vegetation growing from its back. Gardenback was a surrealist script about adultery, featuring a continually growing insect that represented one man's lust for his neighbor. The script would have resulted in a roughly 45-minute-long film, which the AFI felt was too long for such a figurative, nonlinear script.[36]

In its place, Lynch presented Eraserhead, which he had developed based on a daydream of a man's head being taken to a pencil factory by a small boy. Several board members at the AFI were still opposed to producing such a surrealist work, but they were persuaded when dean Frank Daniel threatened to resign if it was vetoed.[37] Eraserhead's script is thought to have been inspired by Lynch's fear of fatherhood;[25] Jennifer had been born with "severely clubbed feet", requiring extensive corrective surgery as a child.[38] Jennifer has claimed that her own unexpected conception and birth defects were the basis for the film's themes.[38]

Pre-production work for Eraserhead began in 1971. However, the staff at the AFI had underestimated the project's scale—they had initially green-lit Eraserhead after viewing a twenty-one page screenplay, assuming that the film industry's usual ratio of one minute of film per scripted page would reduce the film to approximately twenty minutes. This misunderstanding, coupled with Lynch's own meticulous direction, caused the film to remain in production for a number of years.[34] In an extreme example of this labored schedule, one scene in the film begins with Jack Nance's character opening a door—a full year would pass before he was filmed entering the room.[39] Buoyed with regular donations from Fisk and his wife Sissy Spacek, production continued for several years.[40] Additional funds were provided by Nance and his wife, actress Catherine Coulson, who worked as a waitress and donated her income,[41] and by Lynch himself, who delivered newspapers throughout the film's principal photography.[42]

During one of the many lulls in filming, Lynch was able to produce the short film The Amputee, taking advantage of the AFI's wish to test new film stock before committing to bulk purchases. The short piece starred Coulson, who continued working with Lynch as a technician on Eraserhead.[43] Eraserhead's production crew was very small, composed of Lynch; sound designer Alan Splet; cinematographer Herb Cardwell, who left during production and was replaced with Frederick Elmes; production manager and prop technician Doreen Small; and Coulson, who worked in a variety of roles.[44] Lynch began his interest in Transcendental Meditation during the film's production,[25] adopting a vegetarian diet and giving up smoking and alcohol consumption.[45]

After Eraserhead

editEraserhead premièred at the Filmex film festival in Los Angeles, on March 19, 1977.[46] On its opening night, the film was attended by 25 people. The second evening had 24 viewers. Ben Barenholtz, head of distributor Libra Films International based in New York City, persuaded a local theater owner of the Cinema Village to run the film as a midnight feature, where it continued for a year. After this, it ran for ninety-nine weeks at New York's Waverly Cinema, had a year-long midnight run at San Francisco's Roxie Theater from 1978 to 1979, and achieved a three-year tenure at Los Angeles' Nuart Theatre between 1978 and 1981.[47] The film has grossed $7,000,000 in the United States as of 2012[update].[48] Following the release of Eraserhead, Lynch tried to find funding for his next project, Ronnie Rocket, a film "about electricity and a three-foot guy with red hair".[49]

Lynch met film producer Stuart Cornfeld during this time. Cornfeld had enjoyed Eraserhead and was interested in producing Ronnie Rocket; he worked for Mel Brooks and Brooksfilms at the time, and when the two realized that Ronnie Rocket was unlikely to find sufficient financing, Lynch asked to see some already-written scripts to work from for his next film. Cornfeld found four scripts he felt might interest Lynch, but on hearing the name of the first, Lynch decided his next project would be The Elephant Man.[50]

Footnotes

edit- ^ Rodley & Lynch 2005, pp. 109 & 192.

- ^ Rodley & Lynch 2005, p. 245.

- ^ Rodley & Lynch 2005, p. 4.

- ^ a b c Olson 2008, p. 2.

- ^ Rodley & Lynch 2005, p. 3.

- ^ Rodley & Lynch 2005, p. 1.

- ^ a b Rodley & Lynch 2005, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d Odell & Le Blanc 2007, p. 13.

- ^ Rodley & Lynch 2005, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Olson 2008, p. 4.

- ^ Olson 2008, p. 3.

- ^ Olson 2008, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Olson 2008, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Rodley & Lynch 2005, p. 5.

- ^ Rodley & Lynch 2005, p. 6.

- ^ a b Rodley & Lynch 2005, p. 8.

- ^ Olson 2008, p. 23.

- ^ Martin, Rachel (2024-06-13). "David Lynch says he 'died a death' over the way his 'Dune' film turned out". Wild Card with Rachel Martin (Podcast). NPR. Retrieved 2024-09-06.

- ^ a b Olson 2008, p. 20.

- ^ Olson 2008, p. 21.

- ^ Olson 2008, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Williams, Alex (December 31, 2006). "David Lynch's Shockingly Peaceful Inner Life". The New York Times. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ a b c d O'Mahony, John (January 12, 2002). "The Guardian Profile: David Lynch". The Guardian. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ a b Olson 2008, p. 51.

- ^ a b c Woodward, Richard B. (January 14, 1990). "A Dark Lens on America". The New York Times. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2007, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2007, pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b Odell & Le Blanc 2007, p. 22.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2007, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Rodley & Lynch 2005, pp. 44–47.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2007, p. 23.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2007, pp. 23–26.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2007, p. 26.

- ^ a b c Odell & Le Blanc 2007, p. 27.

- ^ Rodley & Lynch 2005, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Olson 2008, pp. 56–59.

- ^ Olson 2008, pp. 59–60.

- ^ a b Olson 2008, p. 87.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2007, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2007, p. 28.

- ^ Rodley & Lynch 2005, p. 67.

- ^ Rodley & Lynch 2005, p. 60.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2007, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Rodley & Lynch 2005, p. 55.

- ^ Olson 2008, p. 72.

- ^ Hoberman & Rosenbaum 1991, p. 215.

- ^ Hoberman & Rosenbaum 1991, p. 220.

- ^ "Eraserhead – Box Office Data, DVD Sales, Movie News, Cast Information". The Numbers. Nash Information Services. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ Rodley & Lynch 2005, p. 91.

- ^ Rodley & Lynch 2005, p. 92.

References

edit- Hoberman, J; Rosenbaum, Jonathan (1991). Midnight Movies. Da Capo. ISBN 0-306-80433-6.

- Odell, Colin; Le Blanc, Michelle (2007). David Lynch. Kamera Books. ISBN 978-1-84243-225-9.

- Olson, Greg (2008). Beautiful Dark (illustrated ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5917-3.

- Rodley, Chris; Lynch, David (2005). Lynch on Lynch (2nd ed.). Macmillan. ISBN 0-571-22018-5.