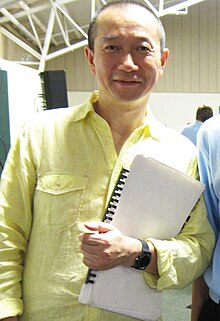

Tan Dun (Chinese: 谭盾; pinyin: Tán Dùn, Mandarin pronunciation: [tʰǎn tu̯ə̂n]; born 18 August 1957) is a Chinese-born American composer and conductor.[1][2] A leading figure of contemporary classical music,[2] he draws from a variety of Western and Chinese influences, a dichotomy which has shaped much of his life and music.[3] Having collaborated with leading orchestras around the world, Tan is the recipient of numerous awards, including a Grawemeyer Award for his opera Marco Polo (1996) and both an Academy Award and Grammy Award for his film score in Ang Lee's Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000). His oeuvre as a whole includes operas, orchestral, vocal, chamber, solo and film scores, as well as genres that Tan terms "organic music" and "music ritual."

Born in Hunan, China, Tan grew up during the Cultural Revolution and received musical education from the Central Conservatory of Music. His early influences included both Chinese music and 20th-century classical music. Since receiving a DMA from Columbia University in 1993, Tan has been based in New York City.[2] His compositions often incorporate audiovisual elements; use instruments constructed from organic materials, such as paper, water, and stone; and are often inspired by traditional Chinese theatrical and ritual performance. In 2013, he was named a UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador.[4]

Biography

editTan Dun was born in 1957 in a village in Changsha in Hunan, China. As a child, he was fascinated by the rituals and ceremonies of the village shaman, which were typically set to music made with natural objects such as rocks and water.[5] Due to the bans enacted during the Cultural Revolution, he was discouraged from pursuing music and was sent to work as a rice planter on the Huangjin commune. He joined an ensemble of other commune residents and learned to play traditional Chinese string instruments. Following a ferry accident that resulted in the death of several members of a Peking opera troupe, Tan Dun was called upon as a violist and arranger. This initial success earned him a seat in the orchestra, and from there he went to study at the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing in 1977.[6] While at the Conservatory, Tan Dun came into contact with composers such as Toru Takemitsu, George Crumb, Alexander Goehr, Hans Werner Henze, Isang Yun, and Chou Wen-Chung, all of whom influenced his sense of musical style.

In 1986, he moved to New York City as a doctoral student at Columbia University, once again studying with Chou Wen-Chung, who had studied under Edgard Varèse. At Columbia, Tan Dun discovered the music of composers such as Philip Glass, John Cage, Meredith Monk, and Steve Reich, and began incorporating these influences into his compositions. He completed his dissertation, Death and Fire: Dialogue with Paul Klee, in 1993.[7] Inspired by a visit to the Museum of Modern Art, Death and Fire is a short symphony that engages with the paintings of Paul Klee.[8] On 15 June 2016, he created the Grand Opening Theme Song of Shanghai Disney Resort. On 1 August 2019 he was appointed as dean of the Bard College Conservatory of Music.

Music

editOpera

editDuring his time at Columbia University, Tan Dun composed his first opera, a setting of nature poems by Qu Yuan called Nine Songs (1989). The poems are sung in both Classical Chinese and contemporary English alongside a small ensemble of Western and Chinese instruments. Among these are a specially built set of 50 ceramic percussion, string, and wind instruments, designed in collaboration with potter Ragnar Naess.[9] To emphasize the shamanistic nature of Qu Yuan's poetry, the actors dance and move in a ritualized manner.[10]

Tan Dun's second work in the genre, Marco Polo (1996), set to a libretto by Paul Griffiths, is an opera within an opera. It begins with the spiritual journey of two characters, Marco and Polo, and their encounters with various historic figures of literature and music, including Dante Alighieri, William Shakespeare, Scheherazade, Sigmund Freud, John Cage, Gustav Mahler, Li Po, and Kublai Khan. These sections are presented in an abstract, Peking opera style. Interwoven with these sections are the travels of the real-life Marco Polo, presented in a Western operatic style.[11] Though the score calls for traditional Western orchestral instrumentation, additional instruments are used to indicate the location of the characters, including recorder, rebec, sitar, tabla, singing bowls, Tibetan horn, sheng, and pipa.[12] The opera won the Grawemeyer Award for Music Composition in 1998.[13]

That same year, Tan Dun premiered his next opera, The Peony Pavilion, an adaptation of Tang Xianzu's 1598 Kunqu play of the same name. Directed by Peter Sellars in its original production, Tan Dun's work is performed entirely in English, though one of the characters must be trained in Peking or Kunqu style. The small ensemble of six musicians performs electronics and Chinese instruments onstage with the actors. Stylistically, the music is a blend of Western avant-garde and Chinese opera.[14]

At this point in his career, Tan Dun had created many works for "organic instruments," i.e. instruments constructed from materials such as paper, water, ceramic, and stone. For his fourth opera, Tea: A Mirror of Soul (2002), co-authored by librettist Xu Ying, organic instruments factor prominently into the structure of the opera itself. The title of each act corresponds to the materials of the instruments being used, as well as the opera's plot. The first act, entitled "Water, Fire", opens with a tea ceremony onstage while percussionists manipulate glass bowls of water. The second act, "Paper", features music on rice paper drums and depicts the characters' search for The Classic of Tea, the first book to codify tea production and preparation in China. The third and final act, "Ceramic, Stones", depicts the death of the protagonist's love. Percussionists play on pitched flowerpots, referred to as "Ceramic chimes" in the score.[15][16]

Tan Dun's most recent opera, The First Emperor (2006), was commissioned by the Metropolitan Opera with the title role created for Plácido Domingo. Co-authored by Tan Dun and Chinese novelist Ha Jin, the opera focuses on the unification of China under Qin Shi Huang, first emperor of the Qin dynasty, and his relationship with the musician Gao Jianli. Like Tan Dun's previous operas, The First Emperor calls for Chinese instruments in addition to a full orchestra, including guzheng and bianzhong. The original Met production was directed by Zhang Yimou, with whom Tan Dun had collaborated on the film Hero.[17]

Film and multimedia

editTan Dun earned more widespread attention after composing the score for Ang Lee's Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000), for which he won an Academy Award, a Grammy Award, and a BAFTA Award.[18][19][20] Other film credits include the aforementioned Hero (Zhang Yimou, 2002), Gregory Hoblit's Fallen (1998), and Feng Xiaogang's The Banquet (2006).

Following the composition of the film score for Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Tan Dun rearranged the music to create the Crouching Tiger Concerto for cello, video, and chamber orchestra. Containing edited footage from the film, this work reverses the role of music in film by treating video as secondary.[21] This same technique was later applied to his film scores for Hero and The Banquet, resulting in the larger work known as the Martial Arts Cycle.[22]

In 2002, Tan Dun continued experimenting with application of video in music The Map, also for cello, video, and orchestra. The Map features documentary footage depicting the lives of China's Tujia, Miao, and Dong ethnic minorities.[23] The musicians onstage, including the cello soloist, interact with the musicians onscreen—a duet of live and recorded performance.[24] The work was premiered and commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra with Yo-Yo Ma.[25]

Tan Dun's most recent multimedia work, Nu Shu: The Secret Songs of Women (2013), is a 13-movement work for video, solo harp, and orchestra. Following years of ethnomusicological research in Hunan, the work captures the sounds of Nüshu script, a phonetic writing system devised by women speakers of the Xiangnan Tuhua dialect who had been disallowed from receiving formal education. Considered a dying language, Tan Dun's research resulted in a series of short films of women singing songs written in Nüshu, which are presented alongside the orchestral performance. As with The Map, the songs in the video are used in counterpoint to the live music.[26]

Orchestral Theatre series

editIn the 1990s, Tan Dun began working on a series of orchestral pieces that would analyze the relationship between performer and audience by synthesizing Western classical music and Chinese ritual. According to the composer,

If we look at the idea of 'art music' with its firm separation of performer and audience, we see that its history is comparatively short. Yet the history of music as an integral part of spiritual life, as ritual, as partnership in enjoyment and spirit, is as old as humanity itself.[27]

In the first piece of the series, Orchestral Theatre I: O (1990), members of the orchestra make various vocalizations—chanting nonsense syllables, for instance—while playing their instruments using atypical techniques. For examples, the harp is played as a gushing, and the violins are played as percussion instruments.[28]

Orchestral Theatre II: Re (1992) expands the concept of ritual by involving the audience. The orchestra is split, with the strings, brass, and percussion onstage, while the woodwinds surround the audience. The score also calls for two conductors, with one facing the stage, and the other facing the audience. The latter conductor cues the audience to hum along with the orchestra in certain sections of the music. The work's namesake derives from humming the solfège pitch "re".[27]

The third piece in the series, Red Forecast (Orchestral Theatre III) (1996), involves more staging elements than its predecessors, adding television monitors, lighting, and even stage directions for the musicians. In this multimedia work, the orchestra is led by both a human conductor and a virtual conductor who appears on the monitors. While the human conductor leads, the monitors depict a variety of images from the 1960s and the Cold War: a collage of Mao Zedong, the Cultural Revolution, Martin Luther King Jr., John F. Kennedy, The Beatles, Nikita Khrushchev, and hydrogen bomb testing. In addition to the video, an audio recording of a weather forecast is played.[29][30]

The final piece in the series, The Gate (Orchestral Theatre IV) (1999), focuses on three women of literary fame: Yu from The Hegemon-King Bids His Concubine Farewell, Juliet from Romeo and Juliet, and Koharu from The Love Suicides at Amijima. Based on the theme of sacrifice for love, The Gate is structured as a theme and variations. The style of each section corresponds to its respective character's country of origin. Additionally, Yu is played by a Peking opera singer (Shi Min), Juliet by a Western opera soprano (Nancy Allen Lundy), and Koharu by a Japanese puppeteer (Jusaburō Tsujimura). As in Orchestra Theatre II: Re, the orchestra is distributed onstage and amongst the audience. The Gate also incorporates video, but unlike the prerecorded images used in Red Forecast, a projection screen displays live images of the three actress-soloists, manipulated in real time by a video artist. The video artist for the 1999 premiere was Elaine J. McCarthy.[31][32]

Organic music

editMany of Tan Dun's works call for instruments made of materials such as paper, stone, or water, but the compositions that he classifies as "organic music" feature these instruments most prominently. The first major work for organic instruments was his Water Concerto for Water Percussion and Orchestra (1998), dedicated to Toru Takemitsu. According to the composer, the sounds made by the soloist are inspired by the sounds of everyday life growing up in Hunan.[33] Basins are filled with water, and the contents are manipulated with bowls, bottles, hands, and other devices. Other water instruments used include the waterphone. Various means of amplification are used, including contact microphones on the basins.[34]

The techniques devised in the Water Concerto were used again in Tan Dun's Water Passion After St. Matthew (2000). Written to commemorate the 250th anniversary of the death of Johann Sebastian Bach, the work for chorus, orchestra, and water percussion follows the Gospel of Matthew, beginning with Christ's baptism. The chorus doubles on tingsha, and the soprano and bass soloists double on xun. The score also requires Mongolian overtone singing from the soloists. As with Orchestral Theatre I: O, members of the orchestra play their instruments with techniques borrowed from non-Western traditions.[35][36]

Tan Dun's next major organic work, Paper Concerto for Paper Percussion and Orchestra (2003), explores the acoustic range of paper. Instruments constructed from differing thicknesses of paper are used as cymbals, drums, or reeds. Additionally, sheets of paper are shaken or struck. These sounds are amplified primarily through wireless microphones worn by the musicians.[37] This work was commissioned by the Los Angeles Philharmonic for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall.[38]

Earth Concerto for stone and ceramic percussion and orchestra (2009) draws from Gustav Mahler's Das Lied von der Erde (The Song of the Earth), which in turn draws from the poetry of Li Po. Ceramic instruments include percussion instruments similar to those Tan Dun had used in previous works, as well as wind instruments and xun.[39]

Symphonies, concertos, and chamber works

editIn the mid-1990s, Tan Dun began working on another series of orchestral works known as the Yi series, named for the I Ching (Yi Jing in pinyin). Each numbered work in the series builds upon the original, Yi°: Concerto for Orchestra (published 2002), by adding a solo instrument. The first concerto in the series, Yi1: Intercourse of Fire and Water (1994), was written for and premiered by cellist Anssi Karttunen.[40] The second work, Yi2: Concerto for Guitar and Orchestra (1996), combines flamenco and pipa techniques and was premiered by Sharon Isbin.[41]

Originally titled Secret Land, Tan Dun wrote a concerto for 12 solo cellos and orchestra called Four Secret Roads of Marco Polo (2004). Commissioned and premiered by the Berlin Philharmonic, the work is a musical exploration of the Silk Road. To achieve these sounds, the cello soloists employ sitar and pipa techniques.[42][43]

Tan Dun wrote a concerto for Lang Lang titled Piano Concerto: "The Fire" (2008), a commission by the New York Philharmonic.[44] The concerto is reportedly inspired by the composer's love for martial arts, and the soloist is instructed to play certain passages of the music with fists and forearms. Other more tranquil sections evoke ancient Chinese instruments such as the guqin.[45]

In 2008, Tan Dun was commissioned by Google and YouTube to write an inaugural symphony for the YouTube Symphony Orchestra (YTSO) project. The resultant work, Internet Symphony No. 1 "Eroica", was recorded by the London Symphony Orchestra and uploaded to YouTube in November 2008, thus beginning the open call for video audition submissions. Voted on by members of the YouTube community as well as professional musicians, the YTSO was assembled of 96 musicians from over 30 countries. In April 2009, a mashup video of the submissions was premiered at Carnegie Hall, followed by a live performance of the work.[46]

Tan Dun has also conducted the BBC Scottish Symphony to record parts of the album Away from Xuan by fellow composer Chen Yuanlin, released in 2009.[47]

He composed a symphonic poem for piano for pianist Yuja Wang titled "Farewell My Concubine for Peking Opera Soprano and Piano". [48] The work was commissioned by Guangzhou Symphony Orchestra and made its world premiere on 31 July 2015 in Xinghai Concert Hall with the orchestra conducted by Long Yu and Wang as piano soloist. [49] [50]

Theatre-inspired works

editThough not explicitly opera, many of Tan Dun's works borrow operatic elements, in terms of both melody and staging. For example, his violin concerto, Out of Peking Opera (1987, revised 1994), quotes jinghu fiddling music often heard in Peking opera.[51] Additionally, Ghost Opera (1994), for pipa and string quartet, includes minimal sets and lighting. Originally composed on commission for Kronos Quartet and Wu Man, Ghost Opera has been performed globally and recorded by Kronos for Nonesuch Records.[52]

List of compositions

editSome of the generic classifications included below are Tan Dun's own concepts, including "organic music" and "music ritual." "Organic music" refers to musical works performed on non-traditional instruments, typically involving organic materials such as paper, water, or stone. "Music ritual" refers to works derived from Chinese spiritual traditions.

Opera

edit- Marco Polo (1995)

- Peony Pavilion (1998)

- Tea: A Mirror of Soul (2002)

- The First Emperor (2006)

- Peony Pavilion (2010)

Symphonic works and concertos

edit- Self Portrait, from "Death and Fire" (1983)

- On Taoism (1985)

- Out of Peking Opera (1987)

- Death and Fire: Dialogue with Paul Klee (1992)

- Concerto for Pizzicato Piano and Ten Instruments (1995)

- Heaven Earth Mankind: Symphony 1997 (1997)

- Overture: Dragon and Phoenix, from Heaven Earth Mankind (1997)

- Requiem and Lullaby, from Heaven Earth Mankind (1997)

- Song of Peace, from Heaven Earth Mankind (1997)

- Yi1: Intercourse of Fire and Water (1994)

- Yi2: Concerto for Guitar and Orchestra (1996)

- 2000 Today: A World Symphony for the Millennium (1999)

- Concerto for String Orchestra and Pipa (1999)

- Concerto for String Orchestra and Zheng (1999)

- Yi°: Concerto for Orchestra (2002)

- Four Secret Roads of Marco Polo (2004)

- Piano Concerto: "The Fire" (2008)

- Internet Symphony (2009)

- Symphony for Strings (2009)

- Symphonic Poem on 3 Notes (2011)

- Atonal Rock n' Roll (2012)

- Concerto for Orchestra (2012)

- Percussion Concerto: "The Tears of Nature" (2012)

- Double Bass Concerto: "Wolf Totem" (2015)[53]

- Passacaglia: Secret of Wind and Birds (2015)[54]

- Farewell My Concubine for Peking Opera Soprano and Piano (2015)

Chamber and solo music

edit- Eight Memories in Watercolor, for piano (1978, 2002)

- Eight Colors for String Quartet (1986)

- In Distance (1987)

- Silk Road, for soprano, voice, and percussion (1989)

- Traces, for piano (1989, 1992)

- Elegy: Snow in June, for cello and percussion (1991)

- Circle with Four Trios, Conductor and Audience (1992)

- Lament: Autumn Wind (1993)

- C A G E, for solo piano (1994)

- A Sinking Love, for soprano and 4 violas da gamba (1995)

- Concerto for Six (1997)

- Concerto for String Quartet and Pipa (1999)

- Dew Drop Falls, for solo piano (2000)

- Seven Desires for Guitar (2002)

- Secret Land, for 12 cellos (2006)

- Violin Concerto: The Love (2009)

- Chiacone—after Colombi, for solo cello (2010)

- Crouching Tiger Sonata for cello and piano (2016)

Organic music

edit- Water Concerto for water percussion and orchestra (1998)

- Paper Concerto for paper percussion and orchestra (2003)

- Water Music (2004)

- Earth Concerto for stone and ceramic percussion with orchestra (2009)

Music ritual

edit- Nine Songs (1989)

- Orchestral Theatre I: O (1990)

- Orchestral Theatre II: Re (1992)

- Ghost Opera

- Red Forecast (Orchestra Theatre III) (1996)

- The Gate (Orchestral Theatre IV) (1999)

- Buddha Passion (2018)

Oratorio

edit- Water Passion (2000)

Movie scores

edit- Don't Cry, Nanking (1995)

- Fallen (1998)

- Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000)

- Hero (2002)

- The Banquet (2010)

Multimedia

edit- Crouching Tiger Concerto, for cello and chamber orchestra (2000)

- The Map: Concerto for Cello, Video and Orchestra (2002)

- Hero Concerto (2010)

- The Banquet (2010)

- Martial Arts Cycle (2013)

- Nu Shu: The Secret Songs of Women (2013)

Recordings

editCD

edit| Year | Title | Performers | Label |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | Nine Songs: Ritual Opera | Crossings Ensemble and Chorus | CRI |

| 1993 | Snow in June | Ed Spanjaard, Arditti Quartet, Nieuw Ensemble, Talujon Percussion Quartet, Susan Botti, Paul Guergerian, Keri-Lynn Wilson, Gillian Benet, Anssi Karttunen | CRI |

| 1994 | On Taoism / Orchestral Theatre I / Death and Fire — Dialogue with Paul Klee | BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra | Koch Schwann |

| 1996 | Chinese Traditional and Contemporary Music | Wu Man & Ensemble | Nimbus Records |

| 1997 | Ghost Opera | Kronos Quartet, Wu Man, George Crumb | Nonesuch Records |

| 1997 | Heaven Earth Mankind: Symphony 1997 | Yo-Yo Ma | Sony Classical |

| 1997 | Marco Polo: An Opera in an Opera | Netherlands Radio Kamerorkest, Cappella Amsterdam | Sony Classical |

| 1999 | Bitter Love (selections from Peony Pavilion) | Ying Huang | Sony Classical |

| 1999 | 2000 Today: A World Symphony for the New Millenium | BBC Concert Orchestra | Sony Classical |

| 2000 | Under the Silver Moon | Susan Glaser, Emily Mitchell, Matthew Gold, Stephanie Griffin | Koch International Classics |

| 2001 | Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon | Shanghai Symphony Orchestra, Shanghai National Orchestra, Shanghai Percussion Ensemble, Yo-Yo Ma, Coco Lee | Sony Classical |

| 2001 | Rouse: Concert de Gaudi / Tan Dun: Concerto for Guitar and Orchestra | Sharon Isbin, Muhai Tang, Gulbenkian Orchestra | Teldec |

| 2002 | Out of Peking Opera / Death and Fire / Orchestra Theatre II: Re | Cho-Liang Lin, Muhai Tang, Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra | Ondine |

| 2002 | Water Passion After St. Matthew | Maya Beiser, Mark O'Connor, Elizabeth Keusch, Stephen Bryant, RIAS Kammerchor | Sony Classical |

| 2004 | Hero (soundtrack) | Kodo, You Yan, Liu Li, Itzhak Perlman | Sony Classical |

| 2004 | Lang Lang: Live at Carnegie Hall (includes Tan Dun's Eight Memories in Watercolor) | Lang Lang | DG |

| 2006 | Majestic Charm | Singapore Chinese Orchestra | – |

| 2006 | The Banquet (soundtrack) | – | – |

| 2008 | Sticks and Stones: Music for Percussion and Strings (features Tan Dun's Snow in June) | Marjorie Bagley, Roger Braun, Michael Carrera, Kristin Agee, Seth Haines, Joseph van Hassel, Steven Huang | Equilibrium |

| 2008 | Tan Dun: Pipa Concerto / Hayashi: Viola Concerto / Takemitsu: Nostalghia | Roman Balashov, Wu Man, Yuri Bashmet, Moscow Soloists | Onyx Classics |

| 2011 | Bach to Tan Dun (includes Tan Dun's Eight Memories in Watercolor) | Beijing Guitar Duo (Su Meng & Wang Yameng) | Tonar Music |

| 2011 | Martial Arts Trilogy | Yo-Yo Ma, Lang Lang, Itzhak Perlman | Sony Classical |

| 2012 | Concerto for Orchestra | Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra | Naxos Records |

| 2015 | The Tears of Nature | Martin Grubinger | – |

DVD

edit- Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2001)

- Hero (2004)

- Lang Lang: Live at Carnegie Hall (2004)

- The Map (2004)

- Tea: A Mirror of Soul (2005)

- The Banquet (2006)

- The First Emperor: Metropolitan Opera (2008)

- Marco Polo (2009)

- Paper Concerto: Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra (2009)

- Water Concerto: Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra (2009)

Awards and honors

edit- Second prize at the Dresden International Weber Chamber Music Composition Competition, 1983, String Quartet: Feng Ya Song[2]

- Academy Award, Best Original Score, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon[18]

- Grammy Award, Best Soundtrack, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon[19]

- BAFTA Award for Best Film Music, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon[20]

- Grawemeyer Award, Music Composition, Marco Polo[13]

- Musical America Composer of the Year, 2003[55]

- Shostakovich Award, 2012[56]

- Bach Prize of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg, 2011[57]

- Musikpreis der Stadt Duisburg, 2005[58]

- The Eugene McDermott Award in the Arts, 1994[59]

- The Glenn Gould Protégé prize, 1996 [60]

References

editCitations

edit- ^ Lee 2003, § para. 1.

- ^ a b c d Hung 2011, p. 601.

- ^ Lee 2003, § para. 2.

- ^ UNESCO. "Tan Dun." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.unesco.org/new/en/unesco/about-us/who-we-are/goodwill-ambassadors/tan-dun/.

- ^ Frank J. Oteri. "Tradition and Innovation: The Alchemy of Tan Dun." Tan Dun Online, 15 October 2007. Accessed 1 November 2013. "My Story – Tan Dun Online". Archived from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2013..

- ^ Central Conservatory of Music. "CCOM Celebrates Its 70th Founding Anniversary." 11 November 2010. Accessed 1 November 2013. http://en.ccom.edu.cn/wn/events/2010f/201209030013.shtml.

- ^ The Department of Music at Columbia University. "Dun, Tan." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://music.columbia.edu/people/bios/tdun.

- ^ Music Sales Group. "Death and Fire: Dialogue with Paul Klee (1992)." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.schirmer.com/composer/work/1561/33554

- ^ Nicole V. Gagné, Historical Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Classical Music (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2012), 139.

- ^ Music Sales Group. "Nine Songs (1989)." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.schirmer.com/composer/work/1561/33568.

- ^ Music Sales Group. "Marco Polo (1995)." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.schirmer.com/composer/work/1561/33573.

- ^ Tan Dun, Marco Polo (New York: G. Schirmer, Inc., 1995).

- ^ a b The Grawemeyer Awards. "Previous Winners." Accessed 1 November 2013. "Previous Winners — University of Louisville". Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2013..

- ^ Music Sales Group. "Peony Pavilion (1998)." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.schirmer.com/composer/work/1561/33582.

- ^ Music Sales Group. "Tea: A Mirror of Soul (2002)." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.schirmer.com/composer/work/1561/33592.

- ^ Tan Dun, Tea: A Mirror of Soul (New York: G. Schirmer, Inc., 2002).

- ^ Music Sales Group. "The First Emperor (2006)." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.schirmer.com/composer/work/1561/35240.

- ^ a b The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. "The Official Academy Awards Database." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://awardsdatabase.oscars.org.

- ^ a b The Recording Academy. "Past Winners Search." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.grammy.com/nominees/search.

- ^ a b "Film: Anthony Asquith Award for Original Film Music in 2001." British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ^ Music Sales Group. "Crouching Tiger Concerto (2000)." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.schirmer.com/composer/work/1561/33553.

- ^ Music Sales Group. "Martial Arts Cycle." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.schirmer.com/composer/work/1561/46821.

- ^ Janet E. Bedell, "The Map: Concerto for Violoncello, Orchestra and Video." Boston Symphony Orchestra, 2007. Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.bsomusic.org/res/multimedia/101207TanDunTheMap.pdf.

- ^ Music Sales Group. "The Map: Concerto for Cello, Video and Orchestra (2002)." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.schirmer.com/composer/work/1561/33565.

- ^ Boston Symphony Orchestra. "World Premieres: The New Millennium." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.bso.org/brands/bso/about-us/historyarchives/archival-collection/world-premieres-at-the-bso/world-premieres-the-new-millennium.aspx.

- ^ The Philadelphia Orchestra. "Yannick Nézet-Séguin and The Philadelphia Orchestra Present Philadelphia Commissions Micro-Festival." 27 August 2013. Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.philorch.org/press-room/news/yannick-n%C3%A9zet-s%C3%A9guin-and-philadelphia-orchestra-present-philadelphia-commissions.

- ^ a b Music Sales Group. "Orchestral Theatre II: Re (1992)." Accessed November 1, 2013. http://www.schirmer.com/composer/work/1561/33578.

- ^ Music Sales Group. "Orchestral Theatre (1990)." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.schirmer.com/composer/work/1561/33571.

- ^ Music Sales Group. "Red Forecast (Orchestral Theatre III) (1996)." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.schirmer.com/composer/work/1561/33583.

- ^ Tan Dun, Red Forecast (Orchestral Theatre III) (New York: G. Schirmer, Inc., 1996).

- ^ Music Sales Group. "The Gate (Orchestral Theatre IV) (1999)." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.schirmer.com/composer/work/1561/33559.

- ^ Tan Dun, The Gate (Orchestral Theatre IV) (New York: G. Schirmer, Inc., 1999).

- ^ Tan Dun, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra & Elmquist, Helen, Water Concerto, DVD.

- ^ Tan Dun, Water Concerto for Water Percussion and Orchestra (New York: G. Schirmer, Inc., 1998).

- ^ Music Sales Group. "Water Passion After St. Matthew (2000)." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.schirmer.com/composer/work/1561/33598.

- ^ Tan Dun, Water Passion After St. Matthew (New York: G. Schirmer, Inc., 2000).

- ^ Tan Dun, Paper Concerto for Paper Percussion and Orchestra (New York: G. Schirmer, Inc., 2003).

- ^ Los Angeles Philharmonic. "Los Angeles Philharmonic Welcomes More Than 3,000 Local School Children to First Preview of New Walt Disney Concert Hall." 20 October 2003. Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.laphil.com/press/los-angeles-philharmonic-welcomes-more-3000-local-school-children-first-preview-of-new-walt Archived 18 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Music Sales Group. "Earth Concerto for stone and ceramic percussion with orchestra (2009)." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.schirmer.com/composer/work/1561/37675.

- ^ Anssi Karttunen. "Repertoire for cello and orchestra." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.karttunen.org/repertoire2.html.

- ^ Sharon Isbin. "Orchestral Repertoire." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.sharonisbin.com/repertoire.html.

- ^ Music Sales Group. "Four Secret Roads of Marco Polo (2004)." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.schirmer.com/composer/work/1561/33580.

- ^ Die 12 Cellisten der Berliner Philharmoniker. "Repertoire: Compositions." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.die12cellisten.de/en/repertoire/compositions.

- ^ Music Sales Group. "Piano Concerto: The Fire (2008)." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.schirmer.com/composer/work/1561/36247.

- ^ Anthony Tommasini, "Composer as Celebrity, Musician as Martial Artist", The New York Times, 11 April 2008, accessed 1 November 2013

- ^ "YouTube Symphony Orchestra 2011 - YouTube". www.youtube.com. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ "Away from Xuan | Innova Recordings". www.innova.mu.

- ^ "Tan Dun Farewell My Concubine (2015)". WiseMusicClassical. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ "Guangzhou Symphony Orchestra, Xinghai Concert Hall, Guangzhou, China — review". The Financial Times. 3 August 2015. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ "Yuja Wang Archived Concerts – 2015". Yuja Wang Archives. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ Music Sales Group. "Out of Peking Opera (1994)." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.schirmer.com/composer/work/1561/33572.

- ^ Music Sales Group. "Ghost Opera (1994)." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.schirmer.com/composer/work/1561/33560.

- ^ Patternroot. "Wolf Totem, Concerto for Double Bass, Dominic Seldis". Accessed 29 December 2014

- ^ "Review: National Youth Orchestra Impresses With Symphonie Fantastique at Carnegie Hall" by Anthony Tommasini. The New York Times, 12 July 2015.

- ^ Columbia Artists Management Inc. "CAMI Joins Musical America in Saluting Deborah Voigt, Vocalist of the Year and Tan Dun, Composer of the Year." 10 December 2002. Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.cami.com/?topic=press&prsid=24.

- ^ Pavel Chusovitin, "Tan Dun Was Awarded the Shostakovich Prize," Yuri Bashmet, accessed November 1, 2013, http://bashmet.com/tan-dun-was-awarded-the-shostakovich-prize-photos/?lang=en

- ^ Kulturpreise. "Bach Preis der Freien und Hansestadt Hamburg." Accessed November 1, 2013. http://www.kulturpreise.de/web/preise_info.php?cPath=8&preisd_id=1677&kpsid=cffee19d20137019698ad8224ac41f15.

- ^ Köhler-Osbahr-Stiftung. "Der Musikpreis der Stadt Duisburg." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://www.koehler-osbahr-stiftung.de/musik/musikpreis.htm.

- ^ Massachusetts Institute of Technology. "The Eugene McDermott Award in the Arts." Accessed 1 November 2013. http://arts.mit.edu/mcdermott/past-recipients/.

- ^ Glenn Gould Protégé prize recipients, http://www.glenngould.ca/protege-prize/[dead link]

Sources

edit- Lee, Joanna C. (2003) [2001]. "Tan Dun". Grove Music Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.42657. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 24 November 2021. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Hung, Eric (March 2011). "Tan Dun Through the Lens of Western Media (Part I)". Notes. 67 (3): 601–618. doi:10.1353/not.2011.0033. JSTOR 23012807. S2CID 191463039.

Further reading

edit- Barone, Joshua (23 July 2021). "Asian Composers Reflect on Careers in Western Classical Music". The New York Times.

- Buruma, Ian (4 May 2008). "Of Musical Import". The New York Times.

- Chang, Peter (Spring–Summer 1991). "Tan Dun's String Quartet "Feng-Ya-Song": Some Ideological Issues". Asian Music. 22 (2): 127–158. doi:10.2307/834310. JSTOR 834310.

- Hong, Li (22 November 2021). "From Stravinsky to Tan Dun, an Everlasting Musical Dialogue Between East and West". Caixin.

- Kouwenhoven, Frank (1 December 1991). "Composer Tan Dun: the Ritual Fire Dancer of Mainland China's New Music". China Information. 6 (3): 1–24. doi:10.1177/0920203X9100600301. S2CID 143370816.

- O'Mahony, John (8 September 2000). "Crossing continents". The Guardian.

- Sheppard, W. Anthony (Summer 2009). "Blurring the Boundaries: Tan Dun's Tinte and The First Emperor". The Journal of Musicology. 26 (3). University of California Press: 285–326. doi:10.1525/jm.2009.26.3.285. JSTOR 10.1525/jm.2009.26.3.285.

- Swed, Mark (5 January 1998). "Opera On The Edge". Los Angeles Times.