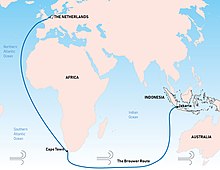

The clipper route was derived from the Brouwer Route and was sailed by clipper ships between Europe and the Far East, Australia and New Zealand. The route, devised by the Dutch navigator Hendrik Brouwer in 1611, reduced the time of a voyage between The Netherlands and Java, in the Dutch East Indies, from almost 12 months to about six months, compared to the previous Arab and Portuguese monsoon route.

The clipper route ran from west to east through the Southern Ocean, making use of the consistently strong westerly winds called the Roaring Forties. Many ships and sailors were lost in the heavy conditions along the route, particularly at Cape Horn, which the clippers had to round on their return to Europe.

The clipper route fell into commercial disuse with the introduction of marine steam engines, and the opening of the Suez and Panama Canals. It remains the fastest sailing route around the world, and has been the route for several prominent yacht races, such as the Velux 5 Oceans Race and the Vendée Globe.

Australia and New Zealand

editThe clipper route from England to Australia and New Zealand, returning via Cape Horn, offered captains the fastest circumnavigation of the world, and hence potentially the greatest rewards. Many grain, wool and gold clippers sailed the route, returning home with valuable cargos in a relatively short time. Because the route ran for much of its length through the Southern Ocean, south of the three great capes (the Cape of Good Hope, Cape Leeuwin and Cape Horn), it exposed ships to the hazards of fierce winds, huge waves, and icebergs. The combination of the fastest ships, the highest risks, and the greatest rewards combined to give the route a particular aura of romance and drama.[1]

Outbound

editThe route ran from England down the east Atlantic Ocean to the Equator, crossing at about the position of Saint Peter and Paul Rocks, around 30 degrees west. A good sailing time for the 3,275 miles (5,271 km) to this point would have been around 21 days. An unlucky ship could spend an additional three weeks crossing the doldrums.[2]

The route then ran south through the western South Atlantic, following the natural circulation of winds and currents, passing close to Trindade, then curving south-east past Tristan da Cunha.[3] The route crossed the Greenwich meridian at about 40 degrees south, taking the clippers into the Roaring Forties after about 6,500 miles (10,500 km) sailed from Plymouth. A good time for that run would have been about 43 days.[4]

Once in the forties, a ship was inside the ice zone, the area of the Southern Ocean where there was a significant chance of encountering icebergs. Safety dictated keeping to the north edge of the zone, roughly along the parallel of 40 degrees south. The great circle route from the Cape of Good Hope to Australia, curving down to 60 degrees south, is 1,000 miles (1,600 km) shorter, and would also offer the strongest winds. Ship masters would therefore go as far south as they dared, weighing the risk of ice against a fast passage.[5]

The clipper ships bound for Australia and New Zealand would call at a variety of ports. A ship sailing from Plymouth to Sydney, for example, would cover around 13,750 miles (22,130 km). A fast time for that passage would be around 100 days.[6] Cutty Sark made the fastest passage on that route by a clipper: 72 days.[7] Thermopylae made the slightly shorter passage from London to Melbourne, 13,150 miles (21,160 km), in just 61 days in 1868–1869.[8]

Homeward

editThe return passage continued east from Australia. Ships stopping at Wellington would pass through the Cook Strait. Otherwise, that tricky passage was avoided, with ships passing instead around the south end of New Zealand.[9] Once again, eastbound ships would be running more or less within the ice zone, staying as far south as possible for the shortest route and strongest winds. Most ships stayed north of the latitude of Cape Horn, at 56 degrees south, following a southward dip in the ice zone as they approached the Horn.[10]

The Horn itself had, and still has, an infamous reputation among sailors. The strong winds and currents, which flow perpetually around the Southern Ocean without interruption, are funnelled by the Horn into the relatively narrow Drake Passage. Coupled with turbulent cyclones coming off the Andes, and the shallow water near the Horn, that combination of factors can create violently hazardous conditions for ships.[11]

After surviving the Horn, ships made the passage back up the Atlantic, following the natural wind circulation up the eastern South Atlantic and more westerly in the North Atlantic. A good run for the 14,750 miles (23,740 km) from Sydney to Plymouth was around 100 days. Cutty Sark made it in 84 days and Thermopylae in 77 days.[12] In 1854–1855, Lightning made the longer passage from Melbourne to Liverpool in 65 days, completing a circumnavigation of the world in 5 months, 9 days, which included 20 days spent in port.[13]

The later windjammers, which were usually large four-masted barques optimized for cargo and handling rather than running, usually made the voyage in 90 to 105 days. The fastest recorded time on Great Grain Races was for the Finnish four-masted barque Parma: 83 days in 1933.[14] Her master on the voyage was the Finnish captain Ruben de Cloux.[15]

Decline and end

editAlready dwindling rapidly due to the advent of modern engines, use of the clipper route was halted entirely by World War II and the consequent near-total interruption of commercial shipping. A few commercial ships using the route still sailed in 1948 and 1949.[16]

Eric Newby chronicled the 1938 final voyage of the four-masted barque Moshulu in his book The Last Grain Race.

Variations

editThe route sailed by a sailing ship was always heavily dictated by the wind conditions, which are generally reliable from the west in the latitude of the forties and fifties. Even there, winds can be variable, and the precise route and distance sailed depended on the conditions on a particular voyage. Ships in the deep Southern Ocean could find themselves faced with persistent headwinds, or even becalmed. Sailing ships attempting to go against the route, however, could have even greater problems.

In 1922, Garthwray attempted to sail west around the Horn carrying cargo from the Firth of Forth to Iquique, Chile. After two attempts to round the Horn the "wrong way", her master gave up and sailed east, reaching Chile from the other direction.[17]

In 1919, attempting to sail from Melbourne to Bunbury, Western Australia, a distance of 2,000 miles (3,200 km), the Garthneill was unable to make way against the forties winds south of Australia, and was faced by strong westerly winds again when she attempted to pass through the Torres Strait to the north. She finally turned and sailed the other way, passing the Pacific, Cape Horn, the Atlantic, the Cape of Good Hope, and the Indian Ocean, to finally arrive in Bunbury after 76 days at sea.[17]

Joshua Slocum, the first person to complete a solo circumnavigation in the Spray, from 1895 to 1898, rounded Cape Horn from east to west. His was not the fastest circumnavigation on record, and he took more than one try to get through Cape Horn.

Modern use of the route

editThe introduction of steam ships, and the opening of the Suez and Panama Canals, spelled the demise of the clipper route as a major trade route. It remains the fastest sailing route around the world, and so the growth in recreational long-distance sailing has brought about a revival of sailing on the route.

The first person to attempt a high-speed circumnavigation of the clipper route was Francis Chichester. Chichester was a notable aviation pioneer, who had flown solo from London to Sydney, and also a pioneer of single-handed yacht racing, being one of the founders of the Single-Handed Trans-Atlantic Race (the OSTAR). After the success of the OSTAR, Chichester started looking into a clipper-route circumnavigation. He wanted to make the fastest ever circumnavigation in a small boat, but specifically set himself the goal of beating a "fast" clipper-ship passage of 100 days to Sydney.[18] He set off in 1966, and completed the run to Sydney in 107 days; after a stop of 48 days, he returned via Cape Horn in 119 days.[19]

Chichester's success inspired several others to attempt the next logical step: a non-stop single-handed circumnavigation along the clipper route. The result was the Sunday Times Golden Globe Race, which was not only the first single-handed round-the-world yacht race, but the first round-the-world yacht race in any format. Possibly the strangest yacht race ever run, it culminated in a successful non-stop circumnavigation by just one competitor, Robin Knox-Johnston, who became the first person to sail the clipper route single-handed non-stop. Bernard Moitessier withdrew from the race after rounding Cape Horn in a promising position. He completed his circumnavigation south of Cape Town and continued to Tahiti, completing another half-circumnavigation.

Today, there are several major races held regularly along the clipper route. The Volvo Ocean Race is a crewed race with stops which sails the clipper route every four years. Two single-handed races, inspired by Chichester and the Golden Globe race, are the Around Alone, which circumnavigates with stops, and the Vendée Globe, which is non-stop.

In March 2005, Bruno Peyron and crew, on the catamaran Orange II, set a new world record for a circumnavigation by the clipper route, of 50 days, 16 hours, 20 minutes, and 4 seconds.[20]

Also in 2005, Ellen MacArthur set a new world record for a single-handed non-stop circumnavigation in the trimaran B&Q/Castorama. Her time along the clipper route of 71 days, 14 hours, 18 minutes, and 33 seconds was the fastest ever circumnavigation of the world by a single-hander.[21] While this record still leaves MacArthur as the fastest female singlehanded circumnavigator, in 2008, Francis Joyon eclipsed the record in a trimaran with a time of 57 days, 13 hours, 34 minutes, and 6 seconds.[21]

See also

editReferences

editFootnotes

edit- ^ Chichester 1966, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Chichester 1966, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Chichester 1966, pp. 47, 54.

- ^ Chichester 1966, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Chichester 1966, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Chichester 1966, p. 7.

- ^ Chichester 1966, p. 8.

- ^ Chichester 1966, p. 68.

- ^ Chichester 1966, p. 121.

- ^ Chichester 1966, p. 134.

- ^ Chichester 1966, pp. 151–152.

- ^ Chichester 1966, pp. 7–8, 68.

- ^ Chichester 1966, p. 69.

- ^ "The Grain Races: Pamir and Parma". Philippe Bellamit. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ^ "section 11". A Visual Encyclopedia of Nautical Terms under Sail. New York: Crown Publishers. 1978. ISBN 9780517533178.

- ^ pamir.chez-alice: The grain races (retrieved 1 December 2006)

- ^ a b Chichester 1966, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Chichester 1967, p. 6.

- ^ Chichester 1967, pp. 105, 218.

- ^ Orange II smashes the round the world sailing record, from Yachts and Yachting

- ^ a b WSSRC Ratified Passage Records – "Round the World, non stop, singlehanded", from the World Sailing Speed Record Council

Bibliography

edit- Chichester, F. (1966). Along the Clipper Way. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 9780345021038.

- Chichester, F. (1967). Gipsy Moth Circles the World. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 9780340004845.