Robert George Seale (born October 22, 1936[1]) is an American political activist and author. Seale is widely known for co-founding the Black Panther Party with fellow activist Huey P. Newton.[2] Founded as the "Black Panther Party for Self-Defense", the Party's main practice was monitoring police activities and challenging police brutality in Black communities, first in Oakland, California,[3] and later in cities throughout the United States.[4]

Bobby Seale | |

|---|---|

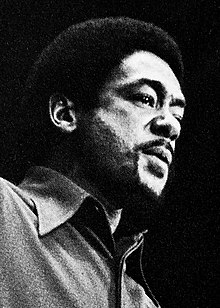

Seale in 1971 | |

| Born | Robert George Seale October 22, 1936 Liberty, Texas, U.S. |

| Education | Merritt College |

| Notable work | Seize the Time: The Story of the Black Panther Party and Huey P. Newton |

| Political party | Black Panther |

| Spouses |

Leslie Johnson (m. 1974) |

Seale was one of the eight people charged by the US federal government with conspiracy charges related to anti-Vietnam War protests in Chicago, Illinois, during the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Seale's appearance in the trial was widely publicized and Seale was bound and gagged for his appearances in court more than a month into the trial for what Judge Julius Hoffman said were disruptions.

Seale's case was severed from the other defendants, turning the "Chicago Eight" into the "Chicago Seven". After his case was severed, the government declined to retry him on the conspiracy charges. Though he was never convicted in the case, Seale was sentenced by Judge Hoffman to four years for criminal contempt of court. The contempt sentence was reversed on appeal.[5]

In 1970, while in prison, Seale was charged and tried as part of the New Haven Black Panther trials over the torture and murder of Alex Rackley, whom the Black Panther Party had suspected of being a police informer. Panther George Sams, Jr., testified that Seale had ordered him to kill Rackley. The jury was unable to reach a verdict in Seale's trial, and the charges were eventually dropped.

Seale's books include A Lonely Rage: The Autobiography of Bobby Seale, Seize the Time: The Story of the Black Panther Party and Huey P. Newton, and Power to the People: The World of the Black Panthers (with Stephen Shames).

Early life edit

Bobby Seale was born in Liberty, Texas, to George Seale, a carpenter, and Thelma Seale (née Traylor), a homemaker.[6] The Seale family lived in poverty during most of his early life. After moving around Texas, first to Dallas, then to San Antonio, and Port Arthur, Seale's family relocated to Codornices Village[7] in Albany, California, during the Great Migration when he was eight years old.[8] Seale attended Berkeley High School, then dropped out in 1955 and joined the United States Air Force.[9] Three years later, a court martial convicted him of fighting with a commanding officer[citation needed] at Ellsworth Air Force Base in South Dakota,[6] resulting in a bad conduct discharge.[10]

Seale subsequently worked as a sheet metal mechanic for various aerospace plants while studying for his high school diploma at night. "I worked in every major aircraft plant and aircraft corporation, even those with government contracts. I was a top-flight sheet-metal mechanic".[11] After earning his high school diploma, Seale attended Merritt Community College where he studied engineering and politics until 1962.[12]

While at college, Bobby Seale joined the Afro-American Association (AAA), a group on the campus devoted to self-education about African and African-American history, along with conversations about philosophy, religion, economics, and politics, including aspects of black separatism.[13][14] "I wanted to be an engineer when I went to college, but I got shifted right away since I became interested in American Black History and trying to solve some of the problems."[15] Through the AAA group, Seale met Huey P. Newton.

In June 1966, Seale began working at the North Oakland Neighborhood Anti-Poverty Center in its summer youth program. Seale's objective was to teach the youth in the program Black American History and also encourage their responsibility toward the people in their communities. While working in the program, Seale met Bobby Hutton, who later became the first recruited member of the Black Panther Party.[16]

Seale married Artie Seale, and they had a son, Malik Nkrumah Stagolee Seale.[17]

Activism and leadership edit

Black Panthers edit

Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton were strongly inspired by the teachings of activist Malcolm X, who had been assassinated in 1965. The two joined together in October 1966 to create the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, which adopted the late activist's slogan "freedom by any means necessary" as their own. Prior to starting the Black Panther Party, Seale and Newton created a group known as the Soul Students Advisory Council. The group was organized to operate through "ultra-democracy", defined as individualism manifesting itself as an aversion to discipline. "The goal was to develop a college campus group that would help develop leadership; to go back to the black community and serve the black community in a revolutionary fashion".[18]

After the inception of Soul Students Advisory Council, Seale and Newton founded the group they are most identified with, the Black Panther Party. They wanted to organize the black community to express their desires and needs in order to resist the racism and classism perpetuated by the system. Seale described the Panthers as "an organization that represents black people and many white radicals relate to this and understand that the Black Panther Party is a righteous revolutionary front against this racist decadent, capitalistic system."[19]

Writing edit

Seale and Newton together wrote the doctrines "What We Want Now!", which Seale said were intended to be "the practical, specific things we need and that should exist", and "What We Believe", which outlines the philosophical principles of the Black Panther Party in order to educate the people and disseminate information about the specifics of the party's platform.[20] These writings were part of the party's Ten-Point Program. Also known as "The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense Ten-Point Platform and Program", this was a set of guidelines to the Black Panther Party's ideals and ways of operation. Seale and Newton named Newton as Minister of Defense and Seale as the Chairman of the party.[21] During his time with the Panthers, Seale was kept under surveillance by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) as part of its illegal COINTELPRO program.[22]

In 1968, Seale wrote Seize the Time: The Story of the Black Panther Party and Huey P. Newton (1970).[23]

The Trial of the Chicago 8 edit

Bobby Seale was one of the original "Chicago Eight" defendants charged with conspiracy and inciting a riot in the wake of the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. While in prison, Seale said, "To be a Revolutionary is to be an Enemy of the state. To be arrested for this struggle is to be a Political Prisoner."[24] The evidence against Seale was slim, as he did not participate in activist planning for the convention's protests and had gone to Chicago as a last-minute replacement for activist Eldridge Cleaver.[25][26] He was in Chicago for only two days of the convention.[26]

During the trial, Judge Julius Hoffman ordered Seale bound and gagged in the courtroom because of his outspoken objections to his personal lack of legal representation. He was repeatedly bound and gagged for several days of the trial.[27][28]

Though he was never convicted in the case, on November 5, 1969, Judge Hoffman sentenced Seale to four years in prison for 16 counts of contempt, each count for three months of imprisonment, because of his outbursts during the trial. He eventually ordered Seale severed from the case. Proceedings against the remaining defendants resulted in their being renamed the "Chicago Seven".[citation needed]

New Haven Black Panther trials edit

While serving his four-year sentence, Seale was tried in 1970 as part of the New Haven Black Panther trials. Several officers of the Panther organization had killed fellow Panther, Alex Rackley, who had confessed under torture to being a police informant.[29] The leader of the murder plan, George W. Sams Jr., turned state's evidence and testified that Seale, who had visited New Haven hours before the murder, had ordered him to kill Rackley. The trials were accompanied by a large demonstration in New Haven on May Day, 1970. This coincided with the beginning of the American college student strike of 1970. The jury was unable to reach a verdict in Seale's trial, and the charges were eventually dropped. The government suspended his contempt convictions, and Seale was released from prison in 1972.[6]

While Seale was in prison, his wife, Artie, became pregnant. Fellow Panther Fred Bennett was said to be the father. Bennett's mutilated remains were found in a suspected Panther hideout in April 1971.[30] Seale was implicated in the murder, with police suspecting he had ordered it in retaliation for the affair, but no charges were pressed.[31]

1973 and 1974 activities edit

In 1973 Seale ran for Mayor of Oakland, California as a Democrat.[32][33] He received the second-most votes in a field of nine candidates[6] but ultimately lost in a run-off with incumbent Mayor John Reading.[32]

In 1974, Seale and Huey Newton argued over a proposed film about the Panthers that Newton wanted Bert Schneider to produce. According to several accounts, the argument escalated to a fight in which Newton, backed by his armed bodyguards, allegedly beat Seale with a bullwhip so badly that Seale required extensive medical treatment for his injuries. Afterward, he went into hiding for nearly a year, and ended his affiliation with the Party that year.[34][35] Seale has denied that any such physical altercation took place, dismissing rumors that he and Newton were ever less than friends.[36]

The Ten Point Platform edit

Seale worked with Huey Newton to create the Ten Point platform. It included political and social demands they believed necessary for the survival of the Black population in the United States. The two men formulated the Ten Point Platform in the late 1960s, and from these ideologies developed the Black Panther Party. The document encapsulated the economic exploitation of the black body, and addressed the mistreatment of the black race. This document was attractive to those suffering under the oppressive nature of white power. The document is based on the conclusion that a combination of racism and capitalism resulted in fascism in the United States. The Ten Point Platform lays out the need for full employment of Black people, decent shelter, and decent education. They defined decent education as the full history of the United States, including acknowledgement of the genocide and displacement of Native Americans and the enslavement of Africans. The platform calls for the release of political prisoners.

The points are as follows:[37]

- We Want Freedom. We Want Power To Determine The Destiny Of Our Black Community.

- We Want Full Employment For Our People.

- We Want An End To The Robbery By The Capitalists Of Our Black Community.

- We Want Decent Housing Fit For The Shelter Of Human Beings.

- We Want Education For Our People That Exposes The True Nature Of This Decadent American Society. We Want Education That Teaches Us Our True History And Our Role In The Present-Day Society.

- We Want All Black Men To Be Exempt From Military Service.

- We Want An Immediate End To Police Brutality And Murder Of Black People.

- We Want Freedom For All Black Men Held In Federal, State, County And City Prisons And Jails.

- We Want All Black People When Brought To Trial To Be Tried In Court By A Jury Of Their Peer Group Or People From Their Black Communities, As Defined By The Constitution Of The United States.

- We Want Land, Bread, Housing, Education, Clothing, Justice And Peace.

Other work edit

In 1978, Seale wrote an autobiography titled A Lonely Rage. Also, in 1987, he wrote a cookbook called Barbeque'n with Bobby Seale: Hickory & Mesquite Recipes, the proceeds going to various non-profit social organizations.[38] Seale also advertised Ben & Jerry's ice cream.[39]

In 1998, Seale appeared on the television documentary series Cold War, discussing the events of the 1960s. Bobby Seale was the central protagonist alongside Kathleen Cleaver, Jamal Joseph and Nile Rodgers in the 1999 theatrical documentary Public Enemy by Jens Meurer, which premiered at the Venice Film Festival. In 2002, Seale began dedicating his time to Reach!, a group focused on youth education programs. He has also taught black studies at Temple University in Philadelphia. Also in 2002, Seale moved back to Oakland, working with young political advocates to influence social change.[1] In 2006, he appeared in the documentary The U.S. vs. John Lennon to discuss his friendship with John Lennon. Seale has also visited over 500 colleges to share his personal experiences as a Black Panther and to give advice to students interested in community organizing and social justice.[citation needed]

Since 2013, Seale has been seeking to produce a screenplay he wrote based on his autobiography, Seize the Time: The Eighth Defendant.[40][41]

Seale co-authored Power to the People: The World of the Black Panthers, a 2016 book with photographer Stephen Shames.[42]

In popular culture edit

- In 1968, Seale was featured in Agnès Varda's documentary, Black Panthers.

- The 1971 the song "Chicago" written by Graham Nash refers to Seale being bound and gagged during the trial.[43]

- The 1973 the poem and song "H2Ogate Blues" by Gil Scott-Heron mentions the chaining and gagging of Seale during the trial.[44]

- In 1987, Seale was portrayed by Carl Lumbly in the HBO television movie, Conspiracy: The Trial of the Chicago 8.

- In 1995, Seale was portrayed by Courtney B. Vance in the cinematic adaptation of Melvin Van Peebles's novel Panther, produced and directed by Mario Van Peebles.

- In 1995, Seale was mentioned in The Simpsons episode "Mother Simpson"; Mona Simpson (mother of Homer) claims to have proofread Seale's cookbook (the abovementioned Barbeque'n with Bobby Seale).[45]

- A character based on Seale appears in Roberto Bolaño's 2004 novel, 2666.[46]

- In 2007, Seale was voiced by Jeffrey Wright in the animated documentary Chicago 10.

- In 2011, Seale was portrayed by Orlando Jones, in the television film The Chicago 8.

- In 2011, Kendrick Lamar mentioned Seale (along with Fred Hampton and Huey Newton) in the song "HiiiPoWeR" from his debut album Section.80.

- In 2020, Seale was portrayed by Yahya Abdul-Mateen II in Aaron Sorkin's Netflix film, The Trial of the Chicago 7.

- In 2021, Seale is mentioned in the film Judas and the Black Messiah by a policeman commenting on a drawing of him tied up at the trial.

- In 2021, Seale is mentioned in the Showtime documentary Attica by inmates who stated he arrived during the riot but appeared disappointed Seale only stayed a few minutes.

Publications edit

- Seale, Bobby (1991) [1970]. Seize the Time: The Story of The Black Panther Party and Huey P. Newton. Baltimore, Maryland: Black Classic Press. ISBN 978-0-933121-30-0.

- Seale, Bobby (1978). A Lonely Rage: The Autobiography of Bobby Seale. New York: Times Books. ISBN 978-0-812907-15-5.

- Seale, Bobby; Shames, Stephen (2016). Power to the People: The World of the Black Panthers. New York: Abrams Books. ISBN 978-1-419722-40-0.

See also edit

References edit

- ^ a b "Bobby Seale Biography". Biography.com. A&E Television Networks. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ "Huey P. Newton". Biography.com. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- ^ "A Huey P. Newton Story - People - Bobby Seale | PBS". www.pbs.org. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ "Black Panthers". HISTORY. March 29, 2023.

- ^ "Chicago 7 prosecutor: 'They were going to try to destroy our trial. And they did a damn good job.'". Herald & Review. October 20, 2020. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Bobby Seale Archived March 16, 2010, at the Wayback Machine at Spartacus Educational

- ^ "HONORING THELMA TRAYLOR SEALE". Congressional Record. 154 (30). February 25, 2008. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ^ Wilkerson, Isabel (September 2016). "The Long-Lasting Legacy of the Great Migration". Smithssonian Magazine.

- ^ Bagley, Mark. Bobby Seale biography Archived June 11, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Penn State University Libraries. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ^ Hendrickson, Paul (March 10, 1978). "Revolutionary At Rest". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- ^ Seale 1991, p. 8.

- ^ "Civil Rights Movement: "Black Power" Era". Shmoop.

- ^ "Bobby Seale (October 22, 1936)". National Archives. August 25, 2016. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ O’Donoghue, Liam (April 7, 2021). ""We're no longer afraid to be Black"". East Bay Yesterday. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ Seale 1991, p. 10.

- ^ Seale 1991, pp. 35, 43.

- ^ Mitchell, Jason (June 15, 2012). "Malcolm X's Influence on the Black Panther Party's Philosophy". History in an Hour. Archived from the original on October 5, 2018.

- ^ Seale 1991, pp. 59–62.

- ^ "On Violent Revolution", The Black Panther Leaders Speak',' pp. 21–22.

- ^ Seale 1991, p. 11.

- ^ Seale 1991, p. 62.

- ^ "Archival newsfilm footage of a Bobby Seale press conference on police intimidation, from 1966". diva.sfsu.edu.

- ^ Seale, Bobby. Seize The Time: The Story of the Black Panther Party (PDF).

- ^ "On Violent Revolution", The Black Panther Leaders Speak, p. 23.

- ^ "Bobby Seale, Bound and Gagged | Political Activists on Trial". Library of Congress.

- ^ a b Epstein, Jason (December 4, 1969). "A Special Supplement: The Trial of Bobby Seale". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- ^ Coffey, Raymond R.; Kloss, James (November 5, 1969). "Mistrial for Panther chief, Seale gets 4 yrs. in jail". No. Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on September 27, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

Seale was gagged and bound to a chair for two and a half days last week after he tussled with the courtroom marshals.

- ^ Shames, Stephen (October 18, 2016). Power to the People: The World of Black Panthers. New York: Abrams. p. 193. ISBN 978-1-4197-2240-0.

- ^ "Two Controversial Cases in New Haven History: The Amistad Affair (1839) and The Black Panther Trials (1970)". Yale University. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- ^ "Remote Panther Hideout was Slaying Scene". The Palm Beach Post. April 21, 1971. p. A4. Retrieved January 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jama Lazerow, Yohuru R. Williams. In Search of the Black Panther Party: New Perspectives on a Revolutionary Movement. Duke University Press. 2006, p. 170.

- ^ a b Bobby Seale Archived February 1, 2014, at the Wayback Machine at Pennsylvania State University's online library

- ^ "Reading Defeats Seale Easily for Oakland Mayor". The New York Times. May 17, 1973. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- ^ Kate Coleman and Paul Avery. "The Party's Over". New Times. July 10, 1978.

- ^ Hugh Pearson, The Shadow of the Panther, 1994.

- ^ "Former Black Panther draws crowd of more than 600". University of Michigan Record. January 23, 1996. Archived from the original on March 15, 2012. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- ^ "Black Panther's Ten-Point Program". www.marxists.org.

- ^ "Robert George Seale". Africawithin.com. Archived from the original on February 8, 2012. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- ^ Gillespie, J. David (2012). Challengers to Duopoly: Why Third Parties Matter in American Two-Party Politics. Univ of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1611171129.

- ^ Obenson, Tambay A. (March 29, 2013). "Bobby Seale Still Fundraising For Scripted Black Panthers Life Story Feature Film". IndieWire.com. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- ^ Whiting, Sam (October 14, 2016). "Bobby Seale, Black Panthers founder, writes his own history". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- ^ "Power to the People: The World of the Black Panthers". PublishersWeekly.com. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- ^ "Mr. Fish in Conversation With Graham Nash". Truthdig. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- ^ "H20-Gate Blues (Watergate Blues)". American Buddha. Archived from the original on May 15, 2012. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- ^ Turner, Chris (May 31, 2012). Planet Simpson: How a cartoon masterpiece documented an era and defined a generation. Ebury. ISBN 9781446447451 – via Google Books.

- ^ Mishan, Ligaya (January 25, 2009). "National Reading '2666' Month: Hardboiled". The New Yorker. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

Further reading edit

- Edited by Mark L. Levine, George C. McNamee and Daniel Greenberg / Foreword by Aaron Sorkin. The Trial of the Chicago 7: The Official Transcript. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020. ISBN 978-1982155094. OCLC 1162494002

- Edited with an introduction by Jon Wiener. Conspiracy in the Streets: The Extraordinary Trial of the Chicago Seven. Afterword by Tom Hayden and drawings by Jules Feiffer. New York: The New Press, 2006. ISBN 978-1565848337

- Pearson, Hugh. The Shadow of the Panther: Huey P. Newton and the Price of Black Power in America. Addison-Wesley, 1994. ISBN 0201483416.

- Edited by Judy Clavir and John Spitzer. The Conspiracy Trial: The extended edited transcript of the trial of the Chicago Eight. Complete with motions, rulings, contempt citations, sentences and photographs. Introduction by William Kunstler and foreword by Leonard Weinglass. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1970. ISBN 0224005790. OCLC 16214206

- Schultz, John. The Conspiracy Trial of the Chicago Seven. Foreword by Carl Oglesby. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020. ISBN 9780226760742. (Originally published in 1972 as Motion Will Be Denied.)

External links edit

- Media related to Bobby Seale at Wikimedia Commons

- Works related to Bobby Seale at Wikisource

- m Quotations related to Bobby Seale at Wikiquote

- American Black Journal, interview, 1978

- Swindle, interview, 2007

- Appearances on C-SPAN