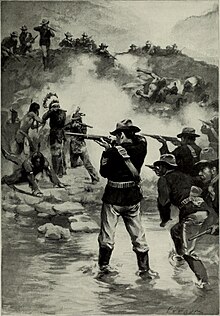

The Battle of Sappa Creek, or Massacre at Cheyenne Hole, was fought on April 23, 1875, between Company H of the Sixth United States Cavalry under the command of Second Lieutenant Austin Henely and a group of Cheyenne Indians led by Little Bull. The conflict took place in modern-day Rawlins County, Kansas, and was both the final and the deadliest battle in the Red River War.

| Battle of Sappa Creek | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Red River War (The Buffalo War) | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| U.S. Army | Cheyenne Indians | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Austin Henely | Little Bull | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Company H, 6th Cavalry Regiment |

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2 dead | Approximately 27 dead | ||||||

The Battle at the Sappa was the result of escalating tensions between Indians, US settlers, and the US Government over the issue of land rights and buffalo hunting. The battle occurred as Henely was chasing after Little Bull's group, which had been sent running in panic caused by a nearby prison break from Black Horse, who was accused of murder, rape, and abuse. When Henely's company caught up with the Indians, they killed all that they could, taking no prisoners. This battle has garnered controversy from several individuals – authors, local settlers, and participants in the fight – over allegations of atrocities committed by Henely and his troops, including ignoring an attempt to parley and burning of living Indians.

Background edit

US-Indian treaties edit

In the 1850s the U.S. government started to try to confine the Indians to specific reservations. In 1867, the Indian Peace Commission was founded to resolve the many conflicts between the Indians and the U.S. government, including U.S. citizens, among the plains. The commission was to negotiate with the Indian tribes and form treaties to get them to move to reservations[1]:11

Little Arkansas edit

In October 1865, the Treaty of Little Arkansas was signed between the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche, and Kiowa Indians as the U.S. Government. The U.S. gave them a reservation covering parts of Kansas, Colorado, and almost all of the Texas panhandle. However, since the Texas panhandle was private land, the U.S. government had no authority to give that land to the Indians.[2]:8-9 Out of the Council of Forty-Four, only 4 chiefs showed up to sign the treaty. One chief, Black Kettle of the Wautapi band, said he spoke for all of the tribes of Cheyenne although he did not.[3]:xvi The Indians were promised firearms for hunting as part of this treaty, however, General Winfield Scott Hancock quickly outlawed the selling of firearms to any Indians. In response, the chiefs sent threats to the U.S. military for breaking the agreements of the treaty. Hancock responded by marching 1400 men from Col. Custer 7th Calvary to the chiefs' villages. He first encountered a large Cheyenne and Sioux village where only two chiefs, Tall Bull and White Horse, came out to meet him. Outraged by this, Hancock threatened to send his army into the village to pull out the chiefs by force. With bad memories of the Sand Creek Massacre in their minds, the Indians started to run and abandon their homes. Hancock, although warned against doing it, burned 250 houses to the ground. President Andrew Johnson removed Hancock from his post and created the Indian Peace Commission in part to repair his actions. His violence against the Cheyenne and Sioux Indians will come to be known as "Hancock's War."[2]:9-10

Medicine Lodge edit

The Indian Peace Commission arranged another treaty at Medicine Lodge Creek on October 21–28, 1867.[1]:12 Only 13 chiefs showed up for this treaty and the Arrow Keeper, the one who binds treaties for the whole tribe, was not in attendance either.[3]:xvii In order to remove the Indians from western Kansas, southwest Nebraska, and eastern Colorado, the treaty put the reservation in modern-day western Oklahoma.[3]:27[1]:12 The Comanches and Kiowas were put in the southwest and the Cheyenne and Arapahos were put to the north. The tribes were promised weapons and ammunition for hunting as well as seeds and farming lessons. It also stated that they would be taught how to build homes and given annuity for 30 years. An important part of the treaty read that the Indians "yet reserve the right to hunt on any lands south of the Arkansas River so long as the buffalo range thereon in such numbers as to justify chase."[1]:12 The Indians understood this to mean that they could hunt in Kansas and Texas, however like the treaty of Little Arkansas, the US Government did not have the authority to let them hunt on the Texas panhandle. At the meeting, the Buffalo Chief said he would let the white settlers build the railroad through his land, but he refused to leave western Kansas and eastern Colorado. Senator John B. Henderson of Missouri took the chiefs aside and told them they could stay on their land until the buffalo were gone if they stood at least 10 miles away from any white settlements or roads. However, this promise was never added to the treaty.[3]:28 In the end, the Indians were not interested in learning from the whites and did not stay on any reservation.[1]:13

President Grant and the Quakers edit

In July 1869, President Grant made an executive order to change the Cheyenne and Arapahoe reservation to the north by the Cherokee Outlet, east by the Cimarron River, south by the Comanche-Kiowa reservation, and west on the 100th meridian. Their agency was moved by Agent Briton Darlington to 125 miles south of Camp Supply, a military outpost, on May 3, 1870.[3]:31 President Grant also established the Peace Policy which established a Board of Indian Commissioners. President Grant wanted to change the responsibility of interacting with the Indians from the military to religious leaders, especially the Quakers. Their goal was to teach them to live like American civilization and convert them to Christianity, but this attempt found little success, although some Indians were converted.[2]:12

Red River War (The Buffalo War) edit

Buffalo hunters edit

A series of disagreements between Indians and settlers surrounding the Buffalo trade led to the retaliation of the Indians to save the buffalo on the western plains. In 1871, Josiah Wright Mooar started the buffalo hide trade in the west. Within a few months the buffalo hide trade became a booming business. Dodge City became the center for the buffalo trade, carrying 750,000 hides in 1873 alone. From 1872 to 1874, 4,373,750 buffalo were killed and shipped along the railroad, with possibly a million more not shipped on the railroad.[1]:13 At first, the hunters respected the hunting rights of the Indians south of the Arkansas River, as outlined in the Medicine Lodge Treaty. However, due to the dwindling numbers of buffalo from the hunters excessive killing, they slowly started hunt into the Indian's territory. By 1873, the hunters constantly entered the Indians territory. It was the U.S. military's job to patrol and guard the border of the territory, but they usually ignored the crossings of the buffalo hunters.

General Philip Sheridan wanted to exterminate the buffalo to terminate the Indians hunting rights. In response to the government wanting to protect the buffalo herds in 1881 he said,

"If I could learn that every buffalo in the northern herd were killed I would be glad...The destruction of this herd would do more to keep the Indians quiet than anything else that could happen. Since the destruction of the southern herd, which formerly roamed from Texas to the Platte, the Indians in that section have given us no trouble."[1]:13-14

The hunters finally decided to go to the south in number and with force in the hopes that the Indians would be too scared to attack them. With them went A. C. Myers, who created a trading post for the hunters called Adobe Wall, built along the Canadian River. The Indians attacked the camps of various hunters, killing Dave Dudley, Tommy Wallace, John Jones, and Blue Billy. Joe Plummer and Anderson Moore avoided these attacks and went to Adobe Wall to tell the others about what happened.[1]:15

Second Battle of Adobe Walls edit

Isatai'i was a Comanche Medicine man and came to be known as a prophet among some of the Indian tribes. Isatai lost his uncle in a raid to Mexico against White men, which led to him swearing revenge against the White man. As a prophet for the Indians, there are reports of his divine powers and accomplishments. He predicted the appearance of a comet, predicted a drought in 1874, claimed to have gone to heaven and back, claimed he could raise the dead, and claimed he could cause bullets to pass through his allies without harm. His most well-known feat was eating a wagonload of bullets, regurgitating them back out, and then eating them again. Isatai gain many followers fast, including some Cheyenne, but mostly to observe him to see if he was worth following.[3]:37

Isatai and a Comanche War chief named Kwahidi formed a war band of 200-250 men, consisting of Indians from the Comanches, Kiowas, and Cheyennes. On the morning of June 27, 1874, Isatai's war party attacked Adobe Wall, while Isatai oversaw the attack from a distance. Only three white men died while between 13 and 35 Indians died in that attack. From then on, many more attacks were made on U.S. military camps and roads.[3]:37-39

When word of the attack on Adobe Wall got to U.S. military, they started making plans for a war immediately. These plans were part of the Indian Campaign of 1874, whose goal was to remove Indians from the southern plains to make way for more American settlements.[1]:16 Although, the Indians did have a sympathizer inside the military, Major General John Pope, who said that the hunters were ruffians who deserved whatever happened to them due to their violence upon the Indians and their illegal acts. He even said if he were to send out military troops it would be to break up these settlements and camps, not to protect them. However, Lieutenant General Philip Sheridan disagreed and saw this as a problem with all of the tribes in the area.[3]:39

On July 3 of that year, 1/4 of the Kiowa warriors accepted to join the Cheyenne and Comanche headmen who planned to lead war against the Whites. However, not all Indians participated and instead some sought refuge in the Indian agencies. The Comanche and Kiowa Indians made attacks in Texas, Kansas, New Mexico, and Colorado. The most notable of these attacks was on July 12 in Lost Valley when Lone Wolf's band attacked Texas rangers led by Major John B. Jones resulting in two rangers dead and two wounded, along with the loss of all of their horses. These attacks led to General Sherman and General Sheridan getting permission to plan a counterattack against the Indians from Secretary of War William W. Belknap on July 20, 1874.[3]:40

The Battle at Sappa Creek edit

Directly Prior to Sappa Creek edit

German Massacre and incarceration edit

Beginning in summer 1874, at least two bands of Cheyenne warriors moved from the south into Kansas to seek revenge on the horse thieves and buffalo hunters they blamed for the Red River War. However, as they rampaged through the area, most of their victims were unsuspecting settlers. One of the warrior bands attacked the German family, a family of nine originally from Georgia.[4]:28 Five of the family members were killed brutally, including both parents, and four of the daughters, ages 5–17, were taken captive by the warriors.[5]:50 During their captivity, the daughters were abused and neglected by their captors. The event became known as the German Massacre (sometimes spelled Germaine in early documents). In the fall, a column of US soldiers led by First Lieutenant Frank D. Baldwin attacked the Cheyenne band who had possession of three of the German sisters. Addie and Julia, the youngest of the sisters, were rescued in this pursuit.[4]:29-31 The harsh winter of 1874-75 combined with relentless army pursuit of the Cheyenne led to Chief Stone Calf's surrender,[3]:50 whereupon he revealed the location of the remaining two living German sisters, who were swiftly rescued.[4]:32

Following the German Massacre, military authorities, especially General Sheridan, ordered that all the “ringleaders” of the Red River War as well as “such as who have been guilty of crimes” were to be incarcerated.[6]:2:897[3]:53 The Attorney General of the United States stated that Sheridan's commission to incarcerate the Indians leaders was illegal. However, since General Sheridan was good friends with President Ulysses S. Grant, President Grant ignored the illegality of the commission and ordered the Indians leaders and those deemed worthy of a crime to be separated from their families and incarcerated. The Indians were brought to or surrendered at the Cheyenne Agency at Darlington, where General Pope assigned Lieutenant Colonel Thomas H. Neill to watch over all of the incoming Indians prisoners.[3]:53 The two eldest German sisters identified nine Cheyenne of Stone Calf's village who had participated in their family's murder and the sisters’ abuse. After these identifications, selection for which Indians were to be incarcerated became random. 33 Cheyenne were selected in total, including a large number of chiefs, mostly chosen based on the unsubstantiated testimony of white men. At one point, Lieutenant Colonel Niell was reportedly intoxicated and in order to fulfill his quota, picked the eighteen right-most Indians to be incarcerated.[7]:365[3]:53 These Indians were put in the guardhouse until they could be brought by train from Oklahoma to Fort Marion, Florida, where they were to be incarcerated.[4]:38-39

Flight of the Cheyennes edit

On April 6, 1875, the Cheyenne prisoners were led to be shackled for their upcoming journey to Fort Marion, Florida. They were taken one by one to a blacksmith who would put a shackle on their legs. Nearby Cheyenne women, upon seeing the shackling, began loudly chanting native war songs.[7]:365-366 Black Horse, one of the prisoners, kicked the blacksmith as he was about to be shackled, and jumped onto a nearby horse to escape. He fled towards the nearby camp of White Horse, just north of the Canadian River[3]:54, where US soldiers followed and shot him before he could tell the camp what followed.[4]:40 Since the Sand Hill Massacre happened nearly two years prior, the Indians assumed something similar was happening again and decided to flee.[3]:54 Many guards raced towards White Horse's village, but could not enter due to the Dog Soldiers who stayed behind to buy the rest of the camp time to flee. The U.S. Sixth Calvary rode up and opened fire, killing one Indian named Big Shell. Captain William A. Rafferty and his men started to move towards the retreated Indians upon a sand hill, however, unbeknownst to him the Indians acquired firearms and opened fire upon him, causing Rafferty and his men to retreat. More U.S. soldiers arrived from Tenth Calvary; however, the Cheyennes held them off until Colonel Neill arrived with a gatling gun, breaking up the Dog Soldiers position.[3]:55-56 However, just as Colonel Neill ordered his men to advance the Dog Soldiers opened fire once more and with nightfall coming, Neill commanded a retreat. Some Indians in White Horse's camp (mostly men) decided to head north to further escape from the U.S. military. General Pope offered amnesty from the sand hill fight for all Indians who would come back to Cheyenne-Arapahoe Agency, which many of the women from White Horse's village did.[3]:56-57

On April 7, those Dog Soldiers reached the camp of Little Bull and told him that the U.S. military was killing Cheyenne near the Indian Agency. Out of fear of the white soldiers coming to kill or capture them, the entire camp packed up and got ready to flee. News of the impending danger spread across the plains to other Indian camps, causing some to seek amnesty in the Indian agency with General Pope. Some Indians, such as chiefs Sand Hill and Bull Elk with their bands, fled in the general direction that Little Bull and his band fled. In total, 200-300 Cheyenne attempted to escape, around 60 of which were in Little Bull's band.[3]:59 Although the exact path of Little Bull's band is not certain, it is speculated that they fled up north of the Canadian River, crossed over to the Cimarron River, then followed along the river north, northwest until they got to Sappa Creek.[3]:61,Map 4 Seven days into their journey, they stopped at Punished Women's Fork to eat and rest for a bit. However, due to lack of food and time to hunt, they decided to steal cattle from a few white cowboys who then rode off to the south.[3]:64 Along the way they picked up Sand Hill and his band, but they also formed new groups with them and then split up along different trails to meet up later. Along the way, Little Bull's new party discovered a buffalo hunter camp, which was empty at the time, so they took whatever supplies they could, which would later lead to their discovery. Finally, they arrived at Sappa Creek and set up camp in the middle of Sappa Creek in order to do some hunting. There were few trees to conceal their presence, however due to the high hills and low valleys, others would have to be close to see it.[3]:65-68

Pursuit of the Cheyennes edit

In mid-April, H Company, consisting of 44 men[3]:95, under the direction of Lieutenant Austin Henely, was sent from their station at Fort Lyon, Colorado Territory, to Fort Wallace, Kansas, to cut off Little Bull's fleeing camp. Henely mobilized remarkably quickly, perhaps seeing the chase as an opportunity for promotion.[4]:49 At Fort Wallace, the company was joined by Homer Wheeler, a local rancher who would serve as the company's guide and scout. The group departed on April 19;[8]:99 however, progress was slow, and they traveled only thirteen miles on their first day.[9] The next day, Henely abandoned half of their equipment and began a forced march toward Smoky Hill River, on the trail of a group of Cheyenne, most likely the group of Indians led by Spotted Wolf. The company lost the trail, and after bivouacking on April 21, determined to head towards the North Fork of Beaver Creek, upon suggestion from Wheeler.[4]:50-51

On April 22, the company met a group of buffalo hunters, whose camp had been robbed while they were out hunting by Little Bull's band mentioned earlier.[8]:105 Three of the buffalo hunters joined the company to help track down the Cheyenne camp: Henry Campbell, Charles Shroeder, and Samuel B. Srach.[4]:51 H Company camped the night about five miles from the Sappa, and Henely sent the buffalo hunters along with Homer Wheeler to locate the camp.[8]:101-102 They searched for three days until they found a hunting party of 12 Cheyenne, 2 of which they captured. The four men continued their search until Wheeler finally found a group of horses owned by the Indians. He could tell they were owned by the Indians since they were not alarmed by his presence.[3]:108-110 The scouts returned to the company around 2:00 am on April 23, and Wheeler led the group to the Indian encampment, where around 60 Indians were sheltered along the Middle Fork of Sappa Creek.[4]:52-53 (although Henely reports it to be the North Fork, this is likely because he was unaware of the smaller fork further north on the Sappa).[4]:x

Fighting commences edit

Before daybreak, Henely commanded Sergeant George Kitchen, along with ten other men of the party, to round up a group of Indian horses grazing on the nearby plateau, and to kill the herders.[3]:114 Another group led by Cpl. Edward C. Sharpless was to protect their supplies. Henely was left with 25 soldiers plus Wheeler and the three hunters to attack the Indians head on.[3]:114 When daylight began to break, an Indian herder spotted the company and ran to warn the Indian camp.[8]:104-105 Henely immediately commanded his men to advance, although the marshy banks made it difficult to cross the river which separated the Cheyenne from the company, and the men lost a carbine and a pistol in the process.[4]:69

The Indians started to prepare themselves by going down into the pits and holes that were in the slopes of the riverbank and started to point their guns at the soldiers.[3]:119 The soldiers made signs, indicting to the Indians to surrender. Although Wheeler swore that they understood those signs, it was unclear whether or not they actually did. The Indians made signs as well; however, the U.S. soldiers were unsure if that was them trying to surrender or if the Indians were trying to communicate among themselves.[3]:120 Eventually, one of the Indians responded in English saying,

"Go 'way, John, Bring back our ponies!"[3]:120

At that point the U.S. soldiers started to dismount, but once they did the Indians opened fire. Henely then ordered his men to form a skirmish line and fire while advancing on the Indians.[3]121,123 According to Cheyenne testimony, the buffalo hunters' long-range guns caused many Indian fatalities, and so much suffering occurred that Little Bull and Dirty Water went out to parley with the soldiers.[7]:368 Some have claimed that Medicine Arrows, the keeper of the sacred maahotse, was at the battle and was killed when he attempted to parley,[10] but this claim is disputed.[4]:xii Sergeant Theodore Papier went out to meet them, then White Bear shot and killed the sergeant, and Henely's troops responded by shooting down Little Bull and Dirty Water.[7]:368 Henely's official report makes no mention of the parley. Henely ordered his men to get into the prone position and the fighting continued like that for another 20 minutes.[3]:124 Wheeler managed to sneak around and shot a few Indians in the head. After a while, the Indians stopped firing, and Henely thinking that the Indians were dead mounted his horse to chase after the other escaped Indians from the village. Just as he mounted two more Indians popped out, one of which was White Bear, but both were quickly shot and killed.[3]:127 One last warrior popped out of the pits and started to move in a strange, side ways hopping manner, for unknown reasons.[3]:128-129 At this point, the Indians started to retreat towards the camp and the soldiers started to surround the camp. The soldiers started to open fire on all of the Indians they could see, with some still resisting by shooting or jumping out from pits.[3]130-131 As the soldiers were moving through the village, Sergeant Fred Platten and Private Marcus Robbins reported seeing one young Cheyenne riding a horse and leading another horse through the camp, then another older Cheyenne mounted the other horse and the two tried to escape together. The younger Cheyenne was shot and killed while the older Cheyenne escaped. A similar story was told among Indians about a young Cheyenne named Little Bear who tried to could have escaped, but at the last moment decided to go back to die with his family, although in this version there was no mention of an extra horse.[3]:131 Henely ordered his men to loot the village and burn it to the ground.[3]:133 According to Henely, the fight lasted 3 hours.[3]:135

Company H suffered two deaths: Sergeant Papier and Private Robert Theims,[9] and no other members of the company were seriously injured. Only one of their horses was killed[3]:136 Death tolls for the Cheyenne are disputed. Both Henely's and a Cheyenne account number the Indian deaths at 27, Henely claims that nineteen Indians warriors and eight women and children were killed,[9] while the Cheyenne account claims that 7 men and 20 women and children were killed by the company.[7]:369 Marcus Robbins, who was involved in the fight, stated that nineteen Indians were killed in total.[11]:199 This was both the final and the deadliest battle of the Red River War.[4]:ix

Henely, following the battle, recommended eight men for the Medal of Honor for their courageous actions in the fight: Marcus M. Robbins, Richard L. Tea, Frederick Platten, James Lowthers, Simpson Hornaday, Peter W. Gardiner, Michael Dawson, and James F. Ayers.[11]:198-199

Aftermath edit

Battlefield souvenirs edit

After the battle was over, some of the men in the company, including Henely, took various souvenirs from the battlefield, including Indian war bonnets,[8]:107 some of which Henely believed to represent high status among the tribe.[4]:92 According to Cheyenne narrative, when Henely later showed a Cheyenne woman the bonnet (belonging to White Bear) as well as a silver belt he had taken, the woman predicted Henely would die violently. A year later, he died of a drowning in Arizona.[7]:369 The company also returned to Fort Wallace with 134 of the Indians' horses they had rounded up before the battle.[3]:138

End of the Red River War edit

In total 3000 men participated in the war. The war last about ten months, with mostly victories for the U.S. Army, due to the U.S. Army vastly outnumbering the Indians, low food supply due to the dwindling buffalo, and harsh winter weather.[1]:17-18[3]:50 Although there was no official surrender of all of the tribes, the war was said to have ended in June 1875 when an Indian leader named Quanah of Kwahada Comanche Indians led his party to Fort Sill to surrender.[1]:18[3]:50 The Battle at Sappa creek took place just two months before, and was said to be the last major battle of the Red River War.[4]:xi[3]:110 More and more Indians flowed into Fort Sill, who were then stripped of their weapons, put into iron cuffs, or sent free to non-aggressor chiefs.[1]:18

Controversy edit

Many different stories exist about what exactly happened at the Battle of Sappa Creek. The first published account was Henely's official report from April 26, 1875.[9] However, the report has been criticized for leaving out important information, such as the Cheyenne attempt at parley.[12]:311 Some, such as Mari Sandoz, have also questioned if the killing of women and children by the company was truly unavoidable,[10] as Henely claimed in his report.[9] Attacks from the Northern Cheyenne in the area three years later was seen widely as justified vengeance on the white men who had massacred their Southern brethren at Sappa Creek.[5]:137

Some notable critics of Henely and the battle include William D. Street, F. M. Lockard, and Mari Sandoz. They began to speculate that atrocities were committed by Austin Henely and his company, beginning with Street's article in Transactions of the Kansas State Historical Society, where he claims the battle was overly violent against the Indians, including the post-battle burning of a living child.[13] Notably, Street was not a firsthand witness of the battle.[14]:382 Lockard, a nearby Kansas settler, furthered these accusations, claiming that any and all surviving Cheyenne were burned alive.[15] Frederick Platten, one of the Medal of Honor recipients who participated in the battle, accused Henely in 1958 of ordering him to shoot a Cheyenne woman and her baby after the fight,[16]:11-12 the only known accusation of atrocities from a firsthand source.[4]:xii

Sandoz published a widely read book entitled Cheyenne Autumn, which suggested that the battle was in reality a massacre, one of the first times the word was used to describe the actions of white men against Indians.[5]:136 However, Sandoz' book has been criticized for factual inaccuracies, such as placing Medicine Arrows' death at the massacre,[4]:xii as well as its dramatic depictions of Henely as a psychotic killer.[5]:137

References edit

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Cruse, J. Brett (2008). The Battles of the Red River War (1st ed.). Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-60344-027-1.

- ^ a b c Haley, James L. (1976). The Buffalo War (1st ed.). Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company Inc. ISBN 0-385-06149-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao Chalfant, William Y (1997). Cheyennes at Dark Water Creek: The Last Fight of the Red River War. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2875-5. OCLC 35770925.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Monnett, John H (1999). Massacre at Cheyenne Hole : Lieutenant Austin Henely and the Sappa Creek Controversy. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 0-87081-527-X. OCLC 43457108.

- ^ a b c d Leiker, James N (2012). The Northern Cheyenne Exodus in History and Memory. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-4370-5. OCLC 814707488.

- ^ Powell, Peter John (1981). People of the Sacred Mountain. Harper & Row. OCLC 312028021.

- ^ a b c d e f Bent, George (2010). Life of George Bent Written From His Letters. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-1577-1. OCLC 696014858.

- ^ a b c d e Wheeler, Homer H (1925). Buffalo Days; Forty Years in the Old West: The Personal Narrative of a Cattleman, Indian Fighter and Army Officer. The Bobbs-Merrill Company. OCLC 1048049878.

- ^ a b c d e Henely, Austin (1875). “Report for the Secretary of War for the Year 1875"

- ^ a b Sandoz, Mari (2005). Cheyenne Autumn. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-9341-0. OCLC 58985601.

- ^ a b Oscar Frederick Keydel, Walter Frederick Beyer (1906). Deeds of Valor. Detroit, Michigan: The Perrien-Keydel Company. OCLC 228677310.

- ^ Kinbacher, Kurt E. (2016). "Contested Events and Conflicting Meanings: Mari Sandoz and the Sappa Creek Cheyenne Massacre of 1875". Great Plains Quarterly. 36 (4): 309–326. doi:10.1353/gpq.2016.0051. ISSN 2333-5092. S2CID 164815671.

- ^ Street, William D. (1907–1908). Cheyenne Indian Massacre on the Middle Fork of the Sappa. Transactions of the Kansas State Historical Society. OCLC 429511929.

- ^ Street, William D. (2015). Twenty-five Years Among the Indians and Buffalo: A Frontier Memoir. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-2166-8. OCLC 929120981.

- ^ Lockard, F. M. (July 1909). "The Battle of Achilles". Kansas Magazine 2, No. 1.

- ^ Way, Thomas E. (1959). Sgt. Fred Platten's Ten Years on the Trail of the Redskins. Williams News Press. OCLC 29174488.