The gold-ringed tanager (Bangsia aureocincta) is a species of bird in the family Thraupidae, endemic to Colombia. It is a plump, relatively short-tailed Tanager with a distinctive gold ring around its face. It inhabits a narrow band of high-altitude cloud forest on the slopes of the western cordillera of the Andes, where it survives on a diet of fruit and insects. The bird is found in small numbers within a limited geographical area, and much of its breeding biology has yet to be described. It is considered a vulnerable species, threatened by habitat loss.

| Gold-ringed tanager | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Thraupidae |

| Genus: | Bangsia |

| Species: | B. aureocincta

|

| Binomial name | |

| Bangsia aureocincta (Hellmayr, 1910)

| |

| |

Taxonomy and systematics

editThe species was first formally described in 1910 as Buthraupis aureocincta by the Austrian ornithologist Carl Eduard Hellmayr, based on a specimen in the collection of the "Zoological Museum of Munich" (probably the Bavarian State Collection of Zoology). The specimen was collected by M.G. Palmer at the 6700 foot level of the Tatamá mountain (Cerro Tatamá) in the Chocó Department of Colombia.[2]

The genus name Bangsia honours the American ornithologist Outram Bangs. The species epithet comes from the Latin aureus - golden, and cinctus - banded.[3]

The species is monotypic - no subspecies have been identified.[4]

In Spanish the bird is known as bangsia de Tatamá or tangará de Tatamá.[5]

Description

editLike the other Bangsia tanagers, the gold-ringed tanager is a plump bird with a relatively short tail. They are approximately 16cm in length and typically weigh between 35-45 grams.[6][7]

Adult birds are mostly dark green with a yellow breast. The prominent "gold ring" facial markings of adults, described below, make the bird easy to identify, with the only possible confusion species being Slaty-capped shrike-vireo.[7]

Detailed descriptions were provided by F. Gary Stiles, based on birds captured at Alto de Pisones in Risaralda Department:[6]: 30

Adult male

editThe head, throat, and sides of the breast are glossy black, with a ring around the olive-green cheeks and auriculars that is formed by the bright yellow postocular and malar stripes and postauricular bar. The centre of the breast is bright orange-yellow; with the remaining underparts being bright olive-green. The bird's back is dark green, with the rump and upper tail coverts a paler, brighter green. The central tail feathers (rectrices) are dull olive while the outer feathers are dusky, edged with olive. The wings are blackish with the wing coverts and secondaries edged with dull blue. The iris is dark red; the bill is black (upper mandible) and horn coloured (lower mandible), and the tarsi and feet are greyish.

Adult female

editThe adult female is similar to the adult male with the main differences being: the "gold ring" facial markings are narrower and more greenish-yellow, the yellow of the breast is duller and less orange, and the green and blue shades of the back and wings are duller.

Subadult

editOnly a single male specimen has been described. It generally resembled the adult male but all plumage colours were duller and more muted. The auriculars and sides of the breast were dark greenish-black and the iris was dark chestnut.

Distribution and habitat

editAltitudinal range

editThe gold-ringed tanager is found on the slopes of the western cordillera of the Andes. Its altitudinal range is from 1350-2195masl, though most birds are found at or above the 1700m level. The only site where the birds are seen at levels as low as 1350m is in the area of San José del Palmar in the Chocó Department. It is thought that this may be related to the absence of the black-and-gold tanager at this site.[8]: 296, 298

At any given site the birds occupy a narrow altitude range of 100-200m, corresponding to the principal cloud interception point of the Pacific slope.[1]

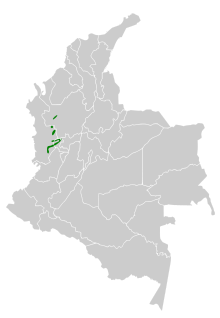

Distribution

editAside from four specimens collected between 1909 and 1949, until recently very little was known about the gold-ringed tanager. Research efforts have now revealed that three small populations exist in the general vicinity of Tatamá massif (Cerro Tatamá), a 4100m peak in the Chocó Department that is the highest point in the Western Andes.[9]

The first of these areas is between the departments of Chocó, Valle del Cauca and Risaralda, in the Serranía de los Paraguas. It includes sites such as the Cerro El Inglés Community Nature Reserve, as well as the Alto de Galápagos which is near the road between San José del Palmar (Chocó) and the village of El Pacifico in the municipality of El Cairo (Valle del Cauca).

The second general area centres around Cerro Montezuma (Montezuma mountain) within Parque Nacional Natural Tatamá. This includes the sites Las Canary Islands in the municipality of Pueblo Rico and the Carramanta massif at Alto de Pisones in the Municipality of Mistrató. On Cerro Montezuma gold-ringed tanagers are seen on the road (Camino Montezuma) that leads to the military base at the top of the hill, and also near the mining settlement in the Quebrada Las Canarias on the western slope of the mountain.

The third known area lies within Antioquia Department and includes the Natural Reserve (RN) Mesenia-Paramillo in the municipality of Jardín, Las Orquídeas National Natural Park, and the Las Tángaras ProAves Reserve in the municipality of El Carmen de Atrato.[10]: 5

Habitat

editGold-ringed tanagers inhabit wet, mossy, mature or secondary Andean Cloud forest, with canopy heights between 9-12m. The areas where they are found are characterized by continuous tracts of natural forest with little or no human intervention. They tend to avoid fragmented forest, pastures and human settlements.[10]: 5 [11]

It has been observed that the bird prefers a very humid habitat. The areas where the species is common tend to be immersed in orographic clouds for prolonged periods each day, whereas in elevation ranges where it is less common it is estimated that orographic clouds would be present for just half of the weather daily.[8]: 296–297

Behaviour and ecology

editBreeding

editRelatively little is known about the breeding biology of the Bangsia tanagers in general and the gold-ringed tanager in particular.[12] This reflects the fact that the birds are accessible in only a few areas, and those areas experienced high levels of violence during the Colombian conflict.[6]: 31 [13] Moreover, during the breeding season this species is known to be silent and elusive, and their nests are well-hidden and difficult to observe.[10]: 5 Any conclusions should therefore be regarded as preliminary.

Birds have been observed feeding juveniles as early as February, and there is one report of bird carrying nesting materials in December. However it appears that the peak breeding period is between May and June, as there are numerous reported sightings of fledglings and juvenile birds in July.[8]: 298 [10]: 5 [12]: 73

On one occasion a nest was observed with a female bird present. Subsequently two different males were seen bringing food items to the nest. This suggests that the species may engage in cooperative breeding.[12]: 72–73

Nest

editThree observations of gold-ringed tanager nesting have been recorded. A female bird was seen carrying moss into a mass of epiphytes on a horizontal limb about 15m above ground. That nest was hidden and could not be further assessed.[6]: 28

A second nest was seen in an inaccessible location 6m above ground on a horizontal branch, hidden under a bromeliad. The same observers found a third nest and, once it was determined to be inactive, examined it. It was a dome-shaped construction located 2.3m above ground in a thin, tall shrub. The stems of two additional shrubs had been bent to provide support to the nest. The measurements of this nest were: width – 23.6cm, length 16.2cm and height 14.5cm. The nest ball was made entirely of moss, with an interior lining of rootlets. The lining of the egg-cup was composed of thin fibers resembling horse hair.[12]: 72

Feeding

editGold-ringed tanagers forage solitarily, in pairs and in family groups, and also join mixed feeding flocks. Males are most likely to be seen foraging alone.[10]: 5

These tanagers usually forage among moss and epiphytes on tree branches, typically from the upper understory to the mid-canopy level. They are often described as moving in a deliberate or even “sluggish” manner. They have been observed bashing fruits against a branch to access the contents.[12]: 71 [8]: 297

They have also been seen pecking at objects on the ground, sometimes in pairs but usually alone, moving and jumping across the floor in a manner likened to that of a swainson’s thrush.[8]: 297

Interactions with other species

editIndividuals and pairs of gold-ringed tanagers have been observed in mixed feeding flocks with a number of species, including red-headed barbet, orange-breasted fruiteater, grey-breasted wood wren, chestnut-breasted chlorophonia, blue-naped chlorophonia, orange-bellied euphonia, common chlorospingus, yellow-throated bush tanager, dusky bush tanager, along with golden, beryl-spangled, ochre-breasted and glistening-green tanagers. Furnariids, woodcreepers, and antwrens were also included in these flocks.[8]: 298 [6]: 28

Within mixed flocks they principally forage for insects, searching deliberately in clumps of moss, mostly along thick horizontal branches.[6]: 28

When gold-ringed and their Bangsia relatives black-and-gold tanagers are present in the same area, they may forage nearby to each other but they do not interact. The two species will rarely be found in the same mixed flock. At fruiting trees the two species seldom coincided in their visits and were not observed to interact when they did so.[8]: 298 [6]: 28

Male gold-ringed tanagers are often aggressive towards other males and individuals of other species. Aggressive interactions have been noted with fulvous-dotted treerunner, black solitaire, glistening-green tanager, purplish-mantled tanager, black-chinned mountain tanager, dusky bush tanager, and three-striped warbler.[8]: 298

Diet

editThe stomachs of collected birds included 70-90% fruit, the remainder was insects. Typical diet items include fruits of the families: Ericaceae, Rubiaceae, Araceae, Cavendishia, Marcgravia, Guettarda, an unidentified mistletoe, Anthurium melastomataceae, and Araliaceae; the latter two seem to be preferred. They also feed on the seeds of Clusia and Tovomita.[8]: 297 [6]: 28, 29

Individuals have also been observed catching insects by sallying out from a perch as a flycatcher would, and one observation has been recorded of a male with a frog in its beak.[8]: 297

Status

editThe gold-ringed tanager is listed Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List and the Colombian Red Book (Libro Rojo). Any species with such a limited range and such specific habitat requirements merits close attention, but the tanager does not seem to experiencing a significant decline at the moment.[1][8]

The rate at which its habitat is being reduced is currently low, but likely to accelerate as the rate of economic development increases in an area that is no longer dominated by insurgent groups. A recent modeling exercise concluded that by the end of 21st century, 24% of the potential habitat for high-altitude forest birds in the Western Andes of Colombia and Ecuador could be lost.[8]: 299

Population

editThe total population of this species, thinly spread as it is over several remote areas, is difficult to quantify. The best available estimate, based on existing records, descriptions of abundance and the amount of available habitat, is 600-1700 mature birds. This number is thought to be consistent with known population density for close relatives with a similar body size, such as the other Bangsia tanager species.[1]

Threats

editDeforestation, primarily the clearing of land for small-scale agriculture; road-building; and an increase in artisanal mining have been identified as the main threats to this species. So far most of the loss of rain forest in the region has been at lower altitudes (1000m and below), but as these areas are exploited pressure is likely to grow on higher altitude regions. The construction of new roads will facilitate the entry of new settlers and new miners.[10][1]

It is felt by some authorities that unregulated tourism is also a threat. They specifically point to an increasing number of birdwatchers who are attracted to the Tatamá massif by its rare and iconic species. It is claimed, albeit without evidence, that large numbers of these birdwatchers are using recordings of the birds’ calls to lure them into range, and it is suspected that such behaviour might interfere with reproduction.[10]

Conservation efforts

editThe Serraniagua Corporation in El Cairo is a social network that works with partners to protect the biodiversity and ecosystems in the area of the Serranía de los Paraguas Mountains and the Tatamá National Park, and specifically the gold-ringed tanager, the cauca guan and the spectacled bear. Their focus is on providing environmental education programmes for the local and indigenous inhabitants, and the creation of a network of community protected areas that act as wildlife corridors.[14]

A group of environmental NGOs led by Calidris (the Association for the study and conservation of aquatic birds in Colombia) has published a proposed management plan for the gold-ringed tanager. It is not known whether this plan has been taken up by the relevant government authorities.[10]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e BirdLife International (2020). "Bangsia aureocincta". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T22722592A180145049. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22722592A180145049.en. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Ogilvie-Grant (Ed.), W.R. (2 March 1910). "Description of two new species of Tanagers from Western Colombia". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. CLVIII: 111–112. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm dictionary of scientific bird names : from aalge to zusii. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 66, 61. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ Gill, F; Donsker, D; Rasmussen, P (Eds.). IOC World Bird List 11.1 (Report). doi:10.14344/IOC.ML.11.1.

- ^ "Gold-ringed Tanager Bangsia aureocincta". Avibase. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Stiles, F. Gary (1998). "Notes on the biology of two threatened species of Bangsia tanagers in northwestern Colombia". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 118 (1). Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ a b Restall, Robin L.; Rodner, Clemencia; Lentino, Miguel (2007). Birds of northern South America : an identification guide. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. Vol 1 p645. ISBN 978-0-300-10862-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Renjifo M., Luis Miguel; Gómez, María Fernanda; Velásquez-Tibatá, Jorge; Amaya-Villarreal, Ángela María; Kattan, Gustavo H.; Amaya-Espinel, Juan David; Burbano-Girón, Jaime (2014). Libro rojo de aves de Colombia, volumen 1, Bosques húmedos de los Andes y la costa pacífica (Primeraición ed.). Bogotá: Editorial Pontificia Universidad Javeriana : Instituto Humboldt. ISBN 978-958-716-671-2.

- ^ "Cerro Tatamá, Colombia". Peakbaggers. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ramírez-Mosquera, D.; García-Ramírez, D.A.; Fierro-Calderón, E.; Zamudio, J.A. (2018). Plan de manejo para la Bangsia de Tatamá (Bangsia aureocincta Hellmayr 1910) (PDF). Cali: Asociación Calidris & Corporación Serraniagua.

- ^ Fierro-Calderón, Eliana; Eusse-González, Diana; Suárez Valbuena, Jessica; Ramírez Mosquera, Diana Patricia (2016). Promoting Conservation of Threatened Birds in Western Colombia - Final Report (PDF). Cali: Asociación Calidris. p. 17.

- ^ a b c d e Freeman, Benjamin G.; Arango, Johhnier A. (2010). "The nest of the Gold-ringed Tanager (Bansia aureocincta), a Colombian endemic". Ornitologia Colombiana (9).

- ^ Farthing, Justin (2001). "A new locality for Gold-ringed Tanager Bangsia aureocincta" (PDF). Cotinga Neotropical Notebook (16): 66-67. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ "Equator Initiative Case Studies: Serrianiagua Corporation" (PDF). UNDP. Retrieved 7 February 2021.