Alice Neel (January 28, 1900 – October 13, 1984) was an American visual artist. Recognized for her paintings of friends, family, lovers, poets, artists, and strangers, Neel is considered one of the greatest American portraitists of the 20th century.[1][2][3] Her career spanned from the 1920s to 1980s.[4]

Alice Neel | |

|---|---|

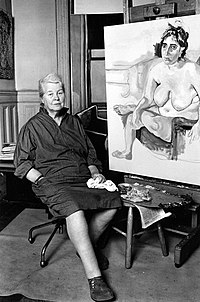

Neel in her studio photographed by Lynn Gilbert (1976) | |

| Born | January 28, 1900 |

| Died | October 13, 1984 (aged 84) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Painting |

| Website | Official website |

Her paintings have an expressionistic use of line and color, psychological acumen, and emotional intensity. She pursued a career as a figurative painter during a period when abstraction was favored, and she did not begin to gain critical praise for her work until the 1960s.[1] Her work contradicts and challenges the traditional and objectified nude depictions of women by her male predecessors.[5] This is done by depicting women through a female gaze, illustrating them as being consciously aware of the objectification by men and the demoralizing effects of the male gaze.[5]

Life and work edit

Early life edit

Alice Neel was born on January 28, 1900,[6][7] in Merion Square, Pennsylvania. Her father was George Washington Neel, an accountant for the Pennsylvania Railroad, and her mother was Alice Concross Hartley Neel.[8] In mid-1900 her family moved to the rural town of Colwyn, Pennsylvania.[8] Young Alice was the fourth of five children with three brothers and a sister. Her siblings were named Hartley, Albert, Lillian, and George Washington Jr.[9] Her oldest brother, Hartley, died of diphtheria shortly after she was born. He was eight years old.[10] She was raised in a straight-laced, lower-middle-class family during a time when there were limited expectations and opportunities for women.[6][11] Her mother had said to her: "I don't know what you expect to do in the world, you're only a girl."[12] From a young age Alice wanted to be an artist, even with little exposure to art.

In 1918, after graduating from high school, she took the civil service exam and got a high-paying clerical position in order to help support her parents.[13] After three years of work, taking art classes by night in Philadelphia, Neel enrolled in the fine art program at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women (now Moore College of Art & Design) in 1921.[14] In her student works she rejected impressionism, the popular style at the time, and instead embraced the Ashcan School of Realism. It is believed this influence came from one of the most prominent figures of the Ashcan School, Robert Henri, who also taught at Philadelphia School of Design for Women.[15] At Philadelphia School of Design for Women, she won honorable mention in her painting class for the Francisca Naiade Balano Prize two years in a row. In 1925 Neel received the Kern Doge Prize for Best Painting in her life class.[16] She graduated from Philadelphia School of Design for Women in 1925.[6][12] Neel often said that she chose to attend an all-girls school so that her temptations for men and boys would not distract her from her art.[citation needed]

Cuba edit

In 1924, Neel met Carlos Enríquez, an upper-class Cuban painter, at the Chester Springs summer school run by PAFA.[7] The couple married on June 1, 1925, in Colwyn, Pennsylvania.[14] Neel soon moved to Havana[6][12] to live with Enríquez's family. In Havana, Neel was embraced by the burgeoning Cuban avant-garde, a set of young writers, artists and musicians. In this environment Neel developed the foundations of her lifelong political consciousness and commitment to equality.[18] Neel later said she had her first solo exhibition in Havana, but there are no dates or locations to confirm this. In March 1927, Neel exhibited with her husband in the 12th Salon des Bellas Artes. This exhibition also included Eduardo Abela, Víctor Manuel García Valdés, Marcelo Pogolotti, and Amelia Peláez who were all part of the Cuban Vanguardia Movement.[19] During this time, she had seven servants and lived in a mansion.[6]

Personal difficulties, themes for art edit

Neel's daughter, Santillana, was born on December 26, 1926, in Havana.[14] In 1927, though, the couple returned to the United States to live in New York.[6] Just a month before Santillana's first birthday, she died of diphtheria.[6] The trauma caused by Santillana's death infused the content of Neel's paintings, setting a precedent for the themes of motherhood, loss, and anxiety that permeated her work for the duration of her career. Shortly following Santillana's death, Neel became pregnant with her second child.[14] On November 24, 1928, Isabella Lillian (called Isabetta) was born in New York City.[14] Isabetta's birth was the inspiration for Neel's Well Baby Clinic, a bleak portrait of mothers and babies in a maternity clinic more reminiscent of an insane asylum than a nursery.

In the spring of 1930, Carlos had given the impression that he was going overseas to look for a place to live in Paris. Instead, he returned to Cuba, taking Isabetta with him. During the time of Enriquez's absence, Neel sublet her New York apartment and traveled to work in the studio of her friends and fellow painters Ethel V. Ashton and Rhonda Myers.[20]

Mourning the loss of her husband and daughter, Neel had a nervous breakdown, was hospitalized, and attempted suicide.[6] She was placed in the suicide ward of the Philadelphia General Hospital.

Even in the insane asylum, she painted. Alice loved a wretch. She loved the wretch in the hero and the hero in the wretch. She saw that in all of us, I think.

— Ginny Neel, Alice's daughter-in-law[6]

Deemed stable almost a year later, Neel was released from the sanatorium in 1931 and returned to her parents' home. Following an extended visit with her close friend and frequent subject, Nadya Olyanova, Neel returned to New York.

-

Mother and Child, 1927

-

After the Death of the Child, 1927

-

Evening at Riverside Park, 1927

-

Untitled Cows in a Field, 1927

Depression era edit

There Neel painted the local characters, including Joe Gould, whom she depicted in 1933 with multiple penises, which represented his inflated ego and "self-deception" about who he was and his unfulfilled ambitions. The painting, a rare survivor of her early works, has been shown at Tate Modern.

During the Depression, Neel was one of the first artists to work for the Works Progress Administration.[21] At the end of 1933, Neel was offered $30 a week to participate in the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) during an interview at the Whitney Museum.[22] She had been living in poverty.[12] While Neel participated in the PWAP and the Works Progress Administration (WPA)/Federal Art Project, her work gained some recognition in the art world. While enrolled in these government programs she painted in a realist style and her subjects were mostly Depression-era street scenes and Communist thinkers and leaders. Some of these sitters included Mother Bloor, the poet Kenneth Fearing, and Pat Whalen.[15] She had an affair with a man named Kenneth Doolittle who was a heroin addict and a sailor. In 1934, he set afire 350 of her watercolors, paintings and drawings.[6][nb 1] At this time, her husband Carlos proposed to reunite, although in the end the couple neither reunited nor officially filed for divorce.[23]

She consorted with artists, intellectuals, and political leaders of the Communist Party, all of whom became subjects for her paintings.[15] Her work glorified subversion and sexuality, depicting whimsical scenes of lovers and nudes, like a watercolor she made in 1935, Alice Neel and John Rothschild in the Bathroom, which showed the naked pair peeing.[6] In the 1930s, Neel gained a reputation as an artist, and established a good standing within her circle of downtown intellectuals and Communist Party leaders. While Neel was never an official Communist Party member, her affiliation and sympathy with the ideals of Communism remained constant. In the 1930s, Neel moved to the Spanish Harlem and began painting her neighbors, specifically women and children.

Female nude portraits edit

The summer of 1930 was a period in her life that she described "as one of her most productive" because that was when she painted her earliest female nudes. Initially Neel preferred painting men to women. She believed women in art represented a dreary way of life consisting of serving men. It was during the time when she felt most vulnerable because of the loss of her children and separation from her husband. That autumn she had a nervous breakdown and had to be institutionalized.[21] Neel's subject matter changed; she went from painting portraits of ordinary people, family, friends, strangers, and well-known art critics to female nudes. The female nude in Western art had always represented a "Woman" as vulnerable, anonymous, passive, and ageless and the quintessential object of the male gaze.[5] However, Neel's female nudes contradicted and "satirized the notion and the standards of the female body."[5] By this sharp contrast to this prevailing idealistic idea of how the female body should be portrayed in art, art historians believe that she was able to free her female sitters from this prevailing ideology that in turn gave them an identity and power. Through her use of "expressive line, vibrant palette, and psychological intensity", Neel did not depict the human body in a realistic manner; it was the way she was able to capture and dignify her sitters' psychological and internal standpoint that made the portraits realistic.[5] For this reason, many art critics today describe Neel's female nudes as truthful and honest portraits, although at the time the works were controversial in the art world because they questioned women's traditional role. Neel often painted women in social interaction or in public spaces, starkly challenging the "Spheres of Femininity" that most 19th-century women artists existed and worked within.[15] In other words, it is believed that Neel challenged the norms of women's role in the household and in everyday life from her paintings. Neel fundamentally changed the way the art establishment viewed the potentialities of the female nude by depicting an unprecedented range of the female experience. [24]

One of Neel's best known early female nude portraits is of Ethel V. Ashton (1930[25]). Neel depicted Ethel, her friend from the Philadelphia School of Design for Women (now part of Moore College of Art and Design), as many art historians described as "nearly crippled with self conscious by her own exposure".[26] Ethel's body was exposed in a crouched seated position, where she was able to look the viewer directly in the eye. Ethel's eyes were commonly described as "soulful" and expressing a sense a fear. Neel painted her friend through a distorted scale that added to the idea of "vulnerability and fearfulness". Neel said of the image: "She's almost apologizing for living. And look at all the furniture she has to carry all the time." By furniture the artist "referred to her heavy thighs, bulging stomach, and pendulous breasts."[27] The formal elements of the painting, light and shadow, the brushstrokes, and the color are suggested to add pathos and humor to the work but they are done in a precise manner to convey a certain tone, which is vulnerability. The painting was exhibited 43 years later at the Alumni Exhibition, where it was severely criticized by many art critics and the general public.[5] The reaction that the painting received was a firm dislike as it was thought it was going against the norms of how female nudes were supposed to be depicted. Ethel, the female nude, saw it on display and "stormed out of rage".[5] The particular painting of the female nude was neither sexual nor flattering to the female form. However, Neel's aim was not to paint the female body in an idealistic way, she wanted to paint in a truthful and honest manner. For this reason she thought of herself as a realist painter.

Post-war years edit

Neel's second son, Hartley, was born in 1941 to Neel and her lover, the communist intellectual Sam Brody. During the 1940s, Neel made illustrations for the Communist publication Masses & Mainstream, and continued to paint portraits from her uptown home. However, in 1943 the Works Progress Administration ceased working with Neel, which made it harder for the artist to support her two sons.[28] During this time, Neel would shoplift and was on welfare to help make ends meet.[29] Between 1940 and 1950, Neel's art virtually disappeared from galleries, save for one solo show in 1944. In the 1950s, her friendship with Mike Gold and his admiration for her social realist work garnered her a show at the Communist-inspired New Playwrights Theatre. In 1959, Neel even made a film appearance after the director Robert Frank asked her to appear alongside a young Allen Ginsberg in his beatnik film, Pull My Daisy. The following year, her work was first reproduced in ARTnews magazine.

Pregnant female nudes edit

By the mid-1960s, many of Neel's female friends had become pregnant which inspired her to paint a series of these women nude. The portraits truthfully highlight instead of hiding the physical changes and emotional anxieties that coexist with childbirth. When she was asked why she painted pregnant nudes, Neel replied,

It isn't what appeals to me, it's just a fact of life. It's a very important part of life and it was neglected. I feel as a subject it's perfectly legitimate, and people out of a false modesty, or being sissies, never show it, but it is a basic fact of life. Also, plastically, it is very exciting ... I think its part of the human experience. Something that primitives did, but modern painters have shied away from because women were always done as sexual objects. A pregnant woman has a claim staked out; she is not for sale.[30]

Neel chose to paint the "basic facts of life" and strongly believed that this form of subject matter is worthy enough to be painted in the nudes,[31] which was what distinguished her from other artists of her time. The pregnant nudes suggested by the art historian, Ann Temkin, allowed Neel to "collapse the imaginary dichotomy that polarizes women into the chaste Madonna or the specter of the dangerous whore"[31] as the portraits were of ordinary women that one sees all around, but not in art.

One of her works that depicted a pregnant female nude is Margaret Evans Pregnant (1978), now in the collection of the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston.[32] Margaret was painted while sitting on upright chair that forced her to expose her pregnant stomach even more, which became the central point in the canvas. Right behind the chair a mirror was placed which allowed the viewer to see the back of her head and neck. However, the mirrored reflection did not look anything like Margaret's frontal portrait. The motive behind this particular section of the painting remains unknown, but art historian Jeremy Lewison says the image is "an uncanny double of the sitter and the artist, presaging older age", and suggests that the reflection is of an older and wiser woman and perhaps a combination of Margaret and Neel's reflection.[33] Pamela Allara says Neel has been accurately characterized as a "sort of artist–sociologist who revived and redirected the dying genre of ameliorative portraiture by merging objectivity with subjectivity, realism with expressionism. In visually interpreting a person's habitus, Neel understood that she could not be an objective observer, that her depictions would of necessity include her own response."[34]

Neel's self-portrait and last paintings edit

Neel painted Kate Millett in 1970, using photographs of Millett[35] to do so, because Millett had refused to pose for Neel. Kate Millett was the author of Sexual Politics.,[36] an important text of second-wave feminism.[37] Alice Neel's career was given new life by the feminist art movement, and Kate Millett was a feminist icon of the time.[38] Neel considered herself "a collector of souls" and she aimed to capture Millett's powerful aura. Neel painted this portrait at a time when many independent women, fighting for equal opportunities and being ignored, were looking for a mentor. In this painting, Kate Millett is directly looking at the viewer, and her stare is very commanding. Kate Millett was featured in the September 25, 2017 issue of Time magazine, in which Time referred to her as the "high priestess" of feminism and to Sexual Politics as the feminist bible.

Neel painted herself in her eightieth year of life, seated on a chair in her studio. She presented herself fully nude. She wore her glasses and held her paintbrush on right hand and an old cloth on the other hand. The white color of her hair and the several creases and folds of her bare skin indicated her old age.[31] As she painted herself seated on the chair her body faced away from the viewer while head was turned towards the viewer. The portrait was completed in 1980 but she had started to paint it five years earlier, before abandoning it for a period of time. However, she was encouraged by her son Richard to complete it and came back to in her early 80s as she was also invited to take part in an exhibition of self-portraits at the Harold Reed Gallery in New York.[31] When Neel's unconventional self-portrait was showcased it attracted considerable attention.[31] Neel painted herself in a truthful manner as she exposed her saggy breasts and belly for everyone to see. Yet again in her last painting, she challenged the social norms of what was acceptable to be depicted in art. Her self-portrait was one of her last works before she died.[26]

On October 13, 1984, Neel died with her family present in her New York City apartment, from advanced colon cancer.[26]

Recognition edit

Toward the end of the 1960s, interest in Neel's work intensified. The momentum of the women's movement led to increased attention, and Neel became an icon for feminists. In 1970, she was commissioned to paint the feminist activist Kate Millett for the cover of Time magazine. Millett refused to sit for Neel; consequently, the magazine cover was based on a photograph.[39]

Her image is included in the iconic 1972 poster Some Living American Women Artists by Mary Beth Edelson.[40]

By the mid-1970s, Neel had gained celebrity and stature as an important American artist. The American Academy and the Institute of Arts and Letters elected Neel in 1976.[15] In 1979, President Jimmy Carter presented her with a National Women's Caucus for Art award for outstanding achievement. Neel's reputation was at its height at the time of her death in 1984.[citation needed]

Neel's life and works are featured in the documentary Alice Neel, which premiered at the 2007 Slamdance Film Festival and was directed by her grandson, Andrew Neel. The film was given a New York theatrical release in April of that year.

Her career was used in a 3-episode series of the Freakonomics podcast "The Hidden Side of the Art Market", illustrating that "the art market is so opaque and illiquid that it barely functions like a market at all".[41]

Neel's work was included in the 2022 exhibition Women Painting Women at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth.[42]

Exhibitions edit

In 1943, Neel's female nude portrait of Ethel Ashton was exhibited at Alumni Exhibition for the very first time, 13 years after the painting was created, and received brutal criticisms from art critics and the general public.[5]

In 1971, Moore College of Art hosted a solo exhibition of alumna Neel's work.[43]

In 1974, Neel's work was given a retrospective exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art,[6] and posthumously, in the summer of 2000, also at the Whitney.

In 1980. she was invited to take part in an exhibition of self-portraits at the Harold Reed Gallery in New York, where her self-portrait was showcased for the first time.[34]

In 2001 the Philadelphia Museum of Art organized a retrospective of her art entitled "Alice Neel".[44]

In 2004, the first exhibition dedicated to Neel's works in Europe was held in London, at the Victoria Miro Gallery. Jeremy Lewison, who had worked at the Tate, was the curator of the collection.[6]

In 2010, Jeremy Lewison and Barry Walker presented, for Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Alice Neel: Painted Truths, on view from March 21 to June 15, 2010,[45] which later went to the Whitechapel Gallery, London and Moderna Museet Malmö, Sweden.[46][47]

In 2013, the first major presentation of the artist's watercolors and drawings, as Alice Neel: Intimate Relations, was on view at Nordiska Akvarellmuseet in Skärhamn, Sweden.[48]

In 2015, Xavier Hufkens began representing The Estate of Alice Neel.[46]

In 2016, the Ateneum, Helsinki presented Alice Neel: Painter of Modern Life, which later went to the Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague, the Fondation Vincent van Gogh Arles, France, and, in 2018, the Deichtorhallen, Hamburg, Germany, from October 10, 2017, to January 14, 2018.[46][49]

In 2017, Hilton Als curated the exhibition "Alice Neel, Uptown" at the Victoria Miro Gallery in London (May 18 – July 29, 2017).[50][51]

In March 2021, a career-spanning retrospective of Neel's work opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[52] Titled "Alice Neel: People Come First", the exhibit featured more than 100 works and was the largest-ever show of Neel's work in New York and the first in two decades.[53]

In September 2021, Alice Neel: People Come First, a retrospective of her work, opened at the Guggenheim Bilbao on September 17 and ran through February 6, 2022. Subsequently, opened at de Young Museum on March 12, 2022, and ran through July 10, 2022.[54][55]

In 2023, Alice Neel: Hot Off The Griddle, the largest exhibition of her work to date in the UK, opened at The Barbican Centre Art Gallery in London running from 16 February until 21 May 2023.[56][57][58][59]

Collections edit

Work by the artist is represented in major museum collections, including:[48]

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Blanton Museum of Art

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

- Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

- Honolulu Museum of Art[60]

- Jewish Museum, New York

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Moderna Museet, Stockholm

- Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

- Museum of Modern Art, New York

- National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.[61]

- National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.[62]

- Philadelphia Museum of Art[63]

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art[64]

- Speed Art Museum, Louisville, Kentucky

- St. Louis Art Museum, St. Louis Missouri

- Tate Modern, London

- Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut

- Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

- Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts

- Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut

See also edit

- The Portrait Now, where it exhibited her self-portrait

- Elizabeth Neel, Neel's granddaughter and an artist

Notes edit

References edit

- ^ a b Neel received an honorary doctorate from the Moore College of Art and Design in 1971. A retrospective of her work was held at the Whitney Museum in 1974. In the last years of her life she finally received extensive national recognition for her paintings. "Alice Neel" Archived June 12, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, BBC, Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- ^ Smee, Sebastian (April 8, 2021). "Alice Neel was the greatest American portraitist of the 20th century. Her work continues to astonish". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved May 1, 2024.

- ^ Smith, Roberta (April 1, 2021). "It's Time to Put Alice Neel in Her Rightful Place in the Pantheon". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 1, 2024.

she is a cult figure, an early feminist, inborn bohemian, erstwhile Social Realist, lifelong activist and staunchly representational painter who bravely persisted, depicting the people and world around her through the heydays of Abstract Expressionism, Pop and Minimalism

- ^ "Alice Neel". Sotheby's. Retrieved July 31, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bauer, Denise (1994). "Alice Neel's Female Nudes". Woman's Art Journal. 15 (2): 21–26. doi:10.2307/1358600. ISSN 0270-7993. JSTOR 1358600.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Mackenzie, Suzie (May 28, 2004). "Heroes and wretches". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 25, 2013. Retrieved December 24, 2013.

- ^ a b Gaze, Delia, ed. (1997). Dictionary of Women Artists. Picture editors: Maja Mihajlovic, Leanda Shrimpton. London. p. 1007. ISBN 978-1884964213.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b "Biography" Archived November 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Aliceneel.com, Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- ^ aliceneeladmin. "Biography". Alice Neel. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ "Alice Neel: American Painter". The Art Story. Archived from the original on October 26, 2016. Retrieved October 26, 2016.

- ^ Hoban, P. (2010). Alice Neel: The Art of Not Sitting Pretty. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 7, ISBN 978-0312607487.

- ^ a b c d e M. Therese Southgate (2011). The Art of JAMA: Covers and Essays from The Journal of the American Medical Association. Oxford University Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0199753833. Archived from the original on January 11, 2014. Retrieved October 10, 2016.

- ^ Munor, Eleanor (2000). Originals : American women artists (New ed., 1. Da Capo Press ed.). Boulder, Colo.: Da Capo Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-0306809552.

- ^ a b c d e "Biography – 1920s" Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, AliceNeel.com, Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Bauer, Denise (2002). "Alice Neel's Feminist and Leftist Portraits of Women". Feminist Studies. 28 (2): 375–395. doi:10.2307/3178749. ISSN 0046-3663. JSTOR 3178749. ProQuest 23317971.

- ^ Lewison, Jeremy (2010). Alice Neel: Painted Truths. Yale University Press. p. 259.

- ^ "Alice Neel | Carlos Enríquez". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved July 31, 2023.

- ^ Meyer, Gerald (Fall 2009). "Alice Neel: The Painter and Her Politics" (PDF). Columbia Journal of American Studies. 9: 149–187. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 3, 2018. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- ^ Lewison, Jeremy (2010). Alice Neel: Painted Truths. p. 259.

- ^ Lewison, Jeremy (2010). Alice Neel: Painted Truths. p. 261.

- ^ a b Hoban, Phoebe (April 22, 2010). "Portraits of Alice Neel's Legacy", The New York Times. Archived February 5, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- ^ Parsons School of Design (1977). New York City WPA art: then 1934–1943 and ... now 1960–1977. New York: NYC WPA Artists. OCLC 5208196.

- ^ "Biography 1930s" Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, AliceNeel.com, Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- ^ Bauer, Denise (October 30, 1994). "Alice Neel's Female Nudes". Woman's Art Journal. 15 (2): 21–26. doi:10.2307/1358600. JSTOR 1358600.

- ^ "'Ethel Ashton', Alice Neel". Tate Modern. Tate. Archived from the original on June 25, 2016. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

Every day she would travel to Philadelphia to work at the studio of Ethel Ashton (1896-1975) and Rhoda Meyers, two friends from the Philadelphia School of Design for Women (now Moore College of Art and Design), where Neel had studied between 1921 and 1925. Lent by the American Fund for the Tate Gallery, courtesy of Hartley and Richard Neel, the artist's sons 2001 L02332

- ^ a b c Hoban, P. (2010). Alice Neel: The Art of Not Sitting Pretty. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0312607487.

- ^ Schor, M. (2009). A Decade of Negative Thinking: Essays On Art, Politics and Daily Life (p. 104) Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- ^ "Alice Neel" Archived March 19, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Smithsonian Institution's National Portrait Gallery, Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- ^ Solomon, Deborah (December 29, 2010). "The Nonconformist", The New York Times. Archived June 13, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- ^ Alice Neel [Motion picture on DVD]. 2007. Arts Alliance America

- ^ a b c d e Allara, P. (1994), Mater of Fact: Alice Neel's Pregnant Nudes, The University of Chicago Press, Vol. 8(2), pp. 6–31

- ^ Neel, Alice (1978), Margaret Evans Pregnant, retrieved November 28, 2023

- ^ Jeremy Lewison, Painted Truths: Showing the Barbarity of Life: Alice Neel's Grotesque.

- ^ a b Allara, P. (2006), "Alice Neel's Women From the 1970s: Backlash to Fast Forward", Woman's Art Journal, Vol. 27(2), pp. 8–10

- ^ "Kate Millet". National Women's Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015.

- ^ Millett, Kate (February 2016). Sexual Politics. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231541725. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016.

- ^ "Feminism". History. February 28, 2019. Archived from the original on March 1, 2019.

- ^ O'Callaghan, Claire (July 31, 2013). "What is a feminist icon?". Feminist Studies Association. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020.

- ^ Solomon, Deborah (December 29, 2010). "The Nonconformist". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 6, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ^ "Some Living American Women Artists/Last Supper". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved January 21, 2022.

- ^ Dubner, Stephen J. (December 1, 2021). ""A Fascinating, Sexy, Intellectually Compelling, Unregulated Global Market."". Freakonomics. Produced by Morgan Levey. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- ^ "Women Painting Women". Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ Hoffmann, Mott, Sharon, Amanda (2008). Moore College of Art & Design. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0738556599 [page needed].

- ^ "Exhibitions – 2001" Archived November 29, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- ^ "Painted Truths" Archived November 29, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Museum of Fine Arts Houston, Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- ^ a b c Westall, Mark (January 26, 2022). "A new exhibition of portraits by Alice Neel". FAD Magazine. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ "Alice Neel: Painted Truths". www.AliceNeel.com. Archived from the original on December 25, 2013. Retrieved December 24, 2013.

- ^ a b Alice Neel Archived February 3, 2014, at the Wayback Machine David Zwirner Gallery.

- ^ "Alice Neel: Painter of Modern Life at Deichtorhallen, Hamburg". Victoria Miro. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- ^ "Alice Neel, Uptown" Archived July 2, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Victoria Miro.

- ^ Adams, Tim (April 29, 2017), "Meet the neighbours: Alice Neel's Harlem portraits", The Observer. Archived May 18, 2017, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Smee, Sebastian (March 25, 2021). "Alice Neel was the greatest American portraitist of the 20th century. Her work continues to astonish". Washington Post. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ Smith, Roberta (April 1, 2021). "It's Time to Put Alice Neel in Her Rightful Place in the Pantheon". New York Times. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ Miranda, Carolina A. (March 19, 2022). "This Sayre Gomez sculpture is a monument to the worst habits of L.A.'s City Council". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

My main reason for heading north, however, was to go marinate in "Alice Neel: People Come First" at the de Young Museum

- ^ Anderson, Sharon (March 2022). "'Alice Neel: People Come First'". Marina Times. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ "Alice Neel: Hot off the Griddle | Barbican". February 16, 2023.

- ^ Hallett, Florence (February 16, 2023). "Nudity, suffering and joy at the Barbican are proof Alice Neel was a collector of souls". i news.

- ^ Luke, Ben (February 15, 2023). "Alice Neel: Hot off the Griddle at the Barbican: Stunningly humane". Evening Standard.

- ^ Frankel, Eddy (February 15, 2023). "Alice Neel: Hot off the Griddle at the Barbican review". Time Out.

- ^ Victoria and the Cat, 1980, accession 6003.1 and Marisol, 1981, oil on canvas, accession 5717.1

- ^ National Gallery of Art. "Neel, Alice". Archived from the original on December 29, 2015. Retrieved August 7, 2014.

- ^ "Self Portrait" Archived March 19, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Smithsonian Institution's National Portrait Gallery, Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- ^ "Collections: Alice Neel" Archived November 29, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- ^ Artwork info Archived November 29, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Alice Neel, Geoffrey Hendricks and Brian, 1978, Retrieved November 27, 2016

Bibliography edit

- Alice Neel [Motion picture on DVD]. 2007. Arts Alliance America

- Allara, P. (2006), "Alice Neel's Women From the 1970s: Backlash to Fast Forward", Woman's Art Journal, Vol. 27 (2), pp. 8–10

- Allara, P. (1994), Mater of Fact: Alice Neel's Pregnant Nudes, The University of Chicago Press, Vol. 8 (2), pp. 6–31

- Hills, Patricia (1995). Alice Neel, Harry N Abrams, Inc., New York. ISBN 0810913585.

- Bauer, D. (1994), "Alice Neel's Female Nudes", Woman's Art Journal, Vol. 15 (2), pp. 21–26

- Hoban, Phoebe (2010). The Art of Not Sitting Pretty, New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312607482.

- Walker, Barry, et al. Alice Neel: Painted Truths, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. ISBN 0300163320.

External links edit

- Official website

- Alice Neel film site

- Finding aid to the Alice Neel papers, 1933–1983 in the Smithsonian Archives of American Art

- Audio recording of lecture by Alice Neel, February 12, 1981, from Maryland Institute College of Art's Decker Library, Internet Archive.

- Jo Adetunji, "The great Alice Neel: 'I wanted to paint as a woman, but not as the oppressive, power-mad world thought a woman should paint'", The Conversation, April 20, 2023.