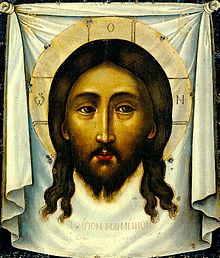

Acheiropoieta (Medieval Greek: αχειροποίητα, lit. 'made without hand'; sg. acheiropoieton) — also called icons made without hands (and variants) — are Christian icons which are said to have come into existence miraculously; not created by a human. Invariably these are images of Jesus or the Virgin Mary. The most notable examples that are credited by tradition among the faithful are, in the Eastern church, the Mandylion,[1] also known as the Image of Edessa, and the Hodegetria, and several Russian icons, and in the West the Shroud of Turin, Veil of Veronica, Our Lady of Guadalupe, and the Manoppello Image. The term is also used of icons that are only regarded as normal human copies of a miraculously created original archetype.

Although the most famous acheiropoieta today are mostly icons painted on wood panel, they exist in other media, such as mosaics, painted tile, and cloth. Ernst Kitzinger distinguished two types: "Either they are images believed to have been made by hands other than those of ordinary mortals or else they are claimed to be mechanical, though miraculous, impressions of the original".[2] The belief in such images became prominent only in the 6th century, by the end of which both the Mandylion and the Image of Camuliana were well known. The pilgrim Antoninus of Piacenza was shown a relic of the Veil of Veronica type in Memphis, Egypt in the 570s.[3]

Background

editSuch images functioned as powerful relics as well as icons, and their images were naturally seen as especially authoritative as to the true appearance of the subject. Like other icon types believed to be painted from the live subject, such as the Hodegetria (thought to have been painted by Luke the Evangelist), they therefore acted as important references for other images in the tradition. They therefore were copied on an enormous scale, and the belief that such images existed, and authenticated certain facial types, played an important role in the conservatism of iconographic traditions such as the depiction of Jesus.[4] Beside, and conflated with, the developed legend of the Image of Edessa, was the tale of the Veil of Veronica, whose name was wrongly interpreted in a typical case of popular etymology to mean "true icon" or "true image", the fear of a "false image" remaining strong.

A further and larger group of images, sometimes overlapping with acheiropoieta in popular tradition, were believed in the Early Middle Ages to have been created by conventional means in New Testament times, often by New Testament figures who, like many monks of the later period, were believed to have practiced as artists. The best known of these, and the most commonly credited in the West, was Saint Luke, who was long believed to have had the Virgin Mary sit for her portrait, but in the East a number of other figures were believed by many to have created images, including narrative ones. Saint Peter was said to have "illustrated his own account of the Transfiguration", Luke to have illustrated an entire Gospel Book, and the late 7th century Frankish pilgrim Arculf reported seeing in the Holy Land a cloth woven or embroidered by the Virgin herself with figures of Jesus and the apostles. The apostles were also said to have been very active as patrons, commissioning cycles in illuminated manuscripts and fresco in their churches.[5]

Such beliefs clearly projected contemporary practices back to the 1st century, and in their developed form are not found before the lead-up to the Iconoclastic Controversy, but in the 4th century, Eusebius, who disapproved of images, accepted that "the features of His apostles Peter and Paul, and indeed of Christ himself, have been preserved in coloured portraits which I have examined".[5] Many famous images, including the Image of Edessa and Hodegetria, were described in versions of their stories as this type of image. The belief that images presumably of the 6th century at the earliest were authentic products of the 1st century distorted any sense of stylistic anachronism, making it easier for further images to be accepted, just as the belief in acheiropoieta, which must have reflected a divine standard of realism and accuracy, distorted early medieval perceptions of what degree of realism was possible in art, accounting for the praise very frequently given to images for their realism, when to modern eyes the surviving corpus has little of this. The standard depictions of both the features of the leading New Testament figures, and the iconography of key narrative scenes, seemed to have their authenticity confirmed by images believed to have been created either by direct witnesses or those able to hear the accounts of witnesses, or alternatively God himself or his angels.[4]

Acheiropoieta of 836

editSuch icons were seen as powerful arguments against iconoclasm. In a document apparently produced in the circle of the Patriarch of Constantinople, which purports to be the record of a (fictitious) Church council of 836, a list of acheiropoieta and icons miraculously protected is given as evidence for divine approval of icons.[citation needed] The acheiropoieta listed are:

- the Image of Edessa, described as still at Edessa;

- the image of the Virgin at Lod, which was said to have miraculously appeared imprinted on a column of a church built by the apostles Peter and John;

- another image of the Virgin, three cubits high, at Lod in Israel, which was said to have miraculously appeared in another church.

The nine other miracles listed deal with the maintenance rather than creation of icons, which resist or repair the attacks of assorted pagans, Arabs, Jews, Persians, scoffers, madmen, and iconoclasts.

This list seems to have had a regional bias, as other then-famous images are not mentioned, such as the Image of Camuliana,[6] later brought to the capital. Another example, and the only one which indisputably still exists, is the mosaic icon of Christ of Latomos in Thessaloniki. This was covered by plaster during the Iconoclastic period, towards the end of which an earthquake caused the plaster to fall down, revealing the image (during the reign of Leo V, 813-20). However, this was only a subsidiary miracle, according to the account extant. This says that the mosaic was being constructed secretly, during the 4th century persecution of Galerius, as an image of the Virgin, when it suddenly was transformed overnight into the present image of Christ.[7]

Notable examples

editImage of Edessa

editAccording to Christian legend, the image of Edessa, (known to the Eastern Orthodox Church as the Mandylion, a Medieval Greek word not applied in any other context), was a holy relic consisting of a square or rectangle of cloth upon which a miraculous image of the face of Jesus was imprinted — the first icon ("image"). According to legend, Abgar V wrote to Jesus, asking him to come cure him of an illness. Abgar received an answering letter from Jesus, declining the invitation, but promising a future visit by one of his disciples. Along with the letter went a likeness of Jesus. This legend was first recorded in the early fourth century by Eusebius,[8] who said that he had transcribed and translated the actual letter in the Syriac chancery documents of the king of Edessa. Instead, Thaddeus of Edessa, one of the seventy disciples, is said to have come to Edessa, bearing the words of Jesus, by the virtues of which the king was miraculously healed.

The first record of the existence of a physical image in the ancient city of Edessa (now Şanlıurfa) was in Evagrius Scholasticus, writing about 600, who reports a portrait of Christ, of divine origin (θεότευκτος), which effected the miraculous aid in the defence of Edessa against the Persians in 544.[9] The image was moved to Constantinople in the 10th century. The cloth disappeared from Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade [Sack of Constantinople] in 1204, reappearing as a relic in King Louis IX of France's Sainte-Chapelle in Paris. It finally disappeared in the French Revolution.[10]

The Ancha icon in Georgia is reputed to be the Keramidion, another acheiropoieta recorded from an early period, miraculously imprinted with the face of Christ by contact with the Mandylion. To art historians, it is a Georgian icon of the 6th-7th century.

Image of Camuliana

editAlthough it is now little known, having probably been destroyed in the period of Byzantine Iconoclasm,[11] the icon of Christ from Camuliana in Cappadocia was the most famous Greek example, certainly from the time it reached Constantinople in 574, after which it was used as a palladium in battles by Philippikos, Priscus and Heraclius, and in the Pannonian Avar Siege of Constantinople in 626, and praised by George Pisida.[12]

Lateran Palace image in Rome

editThis image, also called the Uronica,[13]: 117 is kept in what was once the pope's private chapel, in a room now known as the Sancta Sanctorum at the top of the Scala Sancta in a surviving part of the old Lateran Palace in Rome. The legend is that this image was begun by Luke the Evangelist and finished by angels.

It is thought that the icon was painted in Rome between the 5th and 6th century. Today only slight traces under overpainting remain of the original image of a Christ in Majesty with a crossed halo, in the classic pose of the Teacher holding the Scroll of the Law in his left hand while his right is raised in benediction. Many times restored, the face completely changed when Pope Alexander III (1159–1181) had the present one, painted on silk, placed over the original. Innocent III (1189–1216) covered the rest of the holy icon with an embossed silver riza, but other later embellishments completely covered its surface. It has also been cleaned during the recent restoration.

The doors protecting the icon, also in embossed silver, are of the 15th century. It has a baldachin in metal and gilded wood over it, replacing the one by Caradaossi (1452–1527) lost during the sack of Rome in 1527. The image itself was last inspected by the Jesuit art historian J. Wilpert in 1907.[13]: 120

As early as the reign of Pope Sergius I (687–701) there are records of the image being carried in annual procession at certain feasts, and Pope Stephen II (752–757) carried the image on his shoulders in a procession to counter a threat from the Lombards. By the ninth century its elaborate procession had become a focus of the Feast of the Assumption. In the Middle Ages the Pope and the seven cardinal-bishops would celebrate masses in the small sanctuary where it was housed, and at times would kiss its feet.[13]: 126–128 Although no longer a specific liturgical object, some Romans still venerate this icon, considering it a last hope in disasters and memorable events in the capital, a veneration which can be compared with that for the other ancient icon of the Salus Populi Romani in Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, again in Rome. The former icon used to be taken across Rome annually in procession to "meet" the latter on the Feast of the Assumption.

The Veil of Veronica

editVeronica's Veil, known in Italian as the Volto Santo or Holy Face (but not to be confused with the carved crucifix Volto Santo of Lucca) is a legendary relic. The legend is of medieval origin, and only a feature of the Western church; its connection with any single surviving physical image is slighter still, though a number of images have been associated with it, several probably always meant to be received as copies. The image in the Vatican has a certain priority, if only because of the prestige of the papacy. The nuns of San Silvestro in Capite in Rome were forbidden to exhibit their rival image in 1517 to avoid competition with the Vatican Veronica; it is also now in the Vatican. Like the Genoa image, it is painted on panel and therefore is likely to have always been intended to be a copy.

The legend says that Veronica from Jerusalem encountered Jesus along the Via Dolorosa on the way to Calvary. When she paused to wipe the sweat (Latin suda) off his face with her veil, his image was imprinted on the cloth. The event is commemorated by one of the Stations of the Cross. According to legend, Veronica later traveled to Rome to present the cloth to the Roman Emperor Tiberius. Legend has it that it has miraculous properties, being able to quench thirst, restore sight, and sometimes even raise the dead. Recent studies trace the association of the name with the image[14] to the translation of Eastern relics to the West at the time of the Crusades.

Manoppello Image

editIn 1999, German Jesuit Father Heinrich Pfeiffer, Professor of Art History at the Pontifical Gregorian University,[15] announced at a press conference in Rome that he had found the Veil in a church of the Capuchin monastery, in the small village of Manoppello, Italy, where it had been in the custody of the Capuchin Friars since 1660. The image, known as the Manoppello Image is attested to by Father Donato da Bomba in his "Relatione historica" research tracing back to 1640. Studies in the early 2010s[16] revealed noted congruities with the Shroud.[14] In September 2006 Pope Benedict XVI made a private pilgrimage to the shrine, his first as pope, raising it to the status of a Basilica.

Shroud of Turin

editThe Shroud of Turin (or Turin Shroud) is a linen cloth bearing the hidden image of a man who appears to have been physically traumatized in a manner consistent with crucifixion. The image is clearly visible as a photographic negative, as was first observed in 1898 on the reverse photographic plate when amateur photographer Secondo Pia was unexpectedly allowed to photograph it. The shroud is kept in the royal chapel of the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist in Turin, Italy. The Roman Catholic Church has approved the image's use in association with the devotion to the Holy Face of Jesus and some believe it to be the very cloth that covered Jesus at burial. However, the shroud's linen has been carbon dated, placing its origin in the 13th or early 14th century CE.[17] On this basis, the shroud is all but proven to be a medieval hoax or forgery, or an icon created as such. Nevertheless, it is the subject of intense debate among some scientists, believers, historians, and writers regarding its authenticity and/or the details of its manufacture on account of other peculiarities.

Virgin of Guadalupe

editThis full length image of the Virgin is said to have miraculously been created at the unusually late date of 1531 (for the Western church) in Mexico, where it continues to enjoy an enormous reputation.

In 1979 Philip Callahan, (biophysicist, USDA entomologist, NASA consultant) specializing in infrared imaging, was allowed direct access to visually inspect and photograph the image. He took numerous infrared photographs of the front of the tilma. Taking notes that were later published, his assistant noted that the original art work was neither cracked nor flaked, while later additions (gold leaf, silver plating the Moon) showed serious signs of wear, if not complete deterioration. Callahan could not explain the excellent state of preservation of the un-retouched areas of the image on the tilma, particularly the upper two-thirds of the image. His findings, with photographs, were published in 1981.[18]

Lord of Miracles of Buga

editThis is a tridimensional image of Jesus Christ crucified that comes from the 16th century, and it is attributed to a miraculous event occurred to an Amerindian woman of this South American Andean region, who worked washing clothes for wealthy families of the city of Buga.[citation needed]

On October 5, 2006, a team of specialists, using four different complementary technologies: X-rays, ultraviolet rays, pigment and stratigraphic analysis of the image, certified its well-preserved condition.[citation needed]

Official celebration in the religious Catholic calendar: September 14.[citation needed]

Our Lady of The Pillar

editAccording to ancient Spanish tradition in the early days of Christianity, James the Great, one of the original Twelve Apostles of Jesus Christ, was preaching the Gospel in what was then the pagan land of Caesaraugusta (now Zaragoza), in the Roman province of Hispania. He was disheartened with his mission, having made only a few converts. While he was praying by the banks of the Ebro River with some of his disciples, Mary miraculously appeared before him atop a pillar accompanied by angels. Mary assured James that the people would eventually be converted and their faith would be as strong as the pillar she was standing on. She gave him the pillar as a symbol and a wooden image of herself. James was also instructed to build a chapel on the spot where she left the pillar.

It is generally believed that Mary would have appeared to James through bilocation, as she was still living either in Ephesus or Jerusalem at the time of this event. She is believed to have died three to fifteen years after Jesus' death. After establishing the church, James returned to Jerusalem with some of his disciples where he became a martyr, beheaded in 44 AD under Herod Agrippa. His disciples allegedly returned his body to Spain.

Saint Dominic in Soriano

editMiraculous painting granted to the monastery - (Fra Frangipane) by Virgin Mother of God together with Saint Catherine and saint Magdalene.

Panagia Ierosolymitissa

editThe Panagia Ierosolymitissa (All-Holy Lady of Jerusalem; Greek: Παναγία Ιεροσολυμίτισσα) icon of the Mother of God is an acheiropoieton located in the Tomb of Mary in Gethsemane in Jerusalem. The icon is considered by Orthodox Christians to be the patroness of Jerusalem. The commonly-held story regarding the origins of the Panagia Ierosolymitissa is that it miraculously appeared in the year 1870. This story became popular due to a leaflet released by the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem verifying it.[19]

Icon of Christ of Latomos

editThe Icon of Christ of Latomos (or Latomou), also known as the Miracle of Latomos, is a Byzantine mosaic of Jesus in the monastery of Latomos (now the Church of Hosios (Holy) David the Dendrite) in Thessaloniki, Greece, that is an acheiropoieton.[20] The origins of this mosaic icon can be traced back to the late third century AD when Maximian and Diocletian reigned jointly over the Roman Empire. The Icon of Christ of Latomos is one of the lesser-known acheiropoieta (Greek: αχειροποίητα εικόνα).[20]

According to tradition, the Icon of Christ of Latomos was discovered by Princess Flavia Maximiana Theodora, the Christian daughter of Emperor Maximian. She hid it to protect it from potential damage by the pagan, Roman authorities, and it remarkably survived both Byzantine iconoclasm in the eighth century and a period of time in the fifteenth century when the church of Hosios David was converted to an Islamic mosque (during the Ottoman occupation of Thessaloniki).[21] Sometime before the Ottoman occupation and prior to the twelfth century, the mosaic icon was rediscovered by a monk from Lower Egypt. It was again rediscovered in 1921, and the building was reconsecrated to Saint David.

Thematically and artistically, the Icon of Christ of Latomos is considered to be the first of its type, depicting an apocalyptic scene that includes imagery from the Book of Ezekiel. The icon is also the first to represent important theological ideas about the apocalypse.[20]

See also

edit- Acheiropoietos Monastery in Kyrenia, Cyprus

- Apauruṣeyā

- Church of the Acheiropoietos in Thessaloniki, Greece

- Perceptions of religious imagery in natural phenomena

- Swayambhu

- Holy Face of Lucca

References

edit- ^ Guscin, Mark (2016-02-08). The Tradition of the Image of Edessa. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 137. ISBN 9781443888752.

- ^ Kitzinger, 113

- ^ Kitzinger, 113–114

- ^ a b Grigg, throughout

- ^ a b Grigg, 5–6, 5 quoted

- ^ Mango, Cyril A. (1986). The Art of the Byzantine Empire 312-1453: Sources and Documents. University of Toronto Press. pp. 115–. ISBN 978-0-8020-6627-5.

- ^ Grigg, 6; Cormac

- ^ Eusebius, Historia Ecclesiae 1.13.5 and .22.

- ^ Evagrius, in Jacques Paul Migne, Patrologia Graecalxxxvi, 2, cols. 2748f, noted by Runciman 1931, p. 240, note 5; remarking that "the portrait of Christ has entered the class of αχειροποίητοι icons".

- ^ Two documentary inventories: year 1534 (Gerard of St. Quentin de l'Isle, Paris) and year 1740. See Grove Dictionary of Art, Steven Runciman, Some Remarks on the Image of Edessa, Cambridge Historical Journal 1931, and Shroud.com for a list of the group of relics. See also an image of the Gothic reliquary dating from the 13th century Archived 2008-04-07 at the Wayback Machine, in Histor.ws Archived 2012-02-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Beckwith, 88, although Heinrich Pfeiffer identifies it with the Veil of Veronica and Manoppello Image: Heinrich Pfeiffer, "The concept of "acheiropoietos", the iconography of the face of Christ and the veil of Manoppello", in di Lazzaro, [1]

- ^ Kitzinger, 111-112; Emerick, 356-357. Most fully covered by Von Dobschütz, like most of the images here

- ^ a b c B.M. Bolton, "Advertise the Message: Images in Rome at the Turn of the Twelfth Century", in D. Wood (ed) The Church and the Arts (Oxford, 1992)

- ^ a b The Rediscovered Face - 1 first of four installments of an audiovisual presentation relating the holy image with a number of ancient predecessors, YouTube, access date March 2013.

- ^ Excerpt of Il Volto Santo di Manoppello (The Holy Face of Manoppello), published by Carsa Edizioni in Pescara (page 13) access date March 2013

- ^ Sudarium Christi The Face of Christ Archived 2013-04-01 at the Wayback Machine online audio visual featuring texts by sudarium expert Sr. Blandina Paschalis Schlömer et al.

- ^ Damon, P. E.; D. J. Donahue; B. H. Gore; A. L. Hatheway; A. J. T. Jull; T. W. Linick; P. J. Sercel; L. J. Toolin; C. R. Bronk; E. T. Hall; R. E. M. Hedges; R. Housley; I. A. Law; C. Perry; G. Bonani; S. Trumbore; W. Woelfli; J. C. Ambers; S. G. E. Bowman; M. N. Leese; M. S. Tite (February 1989). "Radiocarbon dating of the Shroud of Turin" (PDF). Nature. 337 (6208): 611–615. Bibcode:1989Natur.337..611D. doi:10.1038/337611a0. S2CID 27686437.

- ^ Callahan, Philip: "The Tilma under Infrared Radiation", CARA Studies in Popular Devotion, vol. II, Guadalupan Studies, No. III (March 1981, 45pp.), Washington, D.C.; cf. Leatham, Miguel (2001). "Indigenista Hermeneutics and the Historical Meaning of Our Lady of Guadalupe of Mexico," Folklore Forum, Google Docs. pp. 34–35.

- ^ Keshman, Anastasia (January 2023). "Panagia Ierosolymitissa Icon -- An Instance in the Mutuality Traditions in the Holy Land of the 19th and 20th Centuries". Marginalia: Art Readings. 1–3. Sofia, Bulgaria: Institute of Art Studies: 307–320 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ a b c Archos, Irene (5 October 2015). "The Unbearded Jesus: The Story of the 5th Century Mosaic of Latomou Monastery St. David of Thessaloniki". Greek American Girl. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ James, Liz; Nicholson, Oliver; Scott, Roger, eds. (2021). "Women remembering women? The 'Miracle in Latomos' motif in medieval Macedonia". After the Text: Byzantine Enquiries in Honour of Margaret Mullett. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781000468717.

Bibliography

edit- Beckwith, John, Early Christian and Byzantine Art, Penguin History of Art (now Yale), 2nd edn. 1979, ISBN 0140560335

- di Lazzaro, Paolo. (ed.), Proceedings of the International Workshop on the Scientific approach to the Acheiropoietos Images, ENEA, 2010, ISBN 978-88-8286-232-9

- Brenda M. Bolton, "Advertise the Message: Images in Rome at the Turn of the Twelfth Century" in Diana Wood (ed) The Church and the Arts (Studies in Church History, 28) Oxford: Blackwell, 1992, pp. 117–130.

- Cormack, Robin, Writing in Gold: Byzantine Society and its Icons, London: George Philip, 1985, ISBN 0-540-01085-5.

- Ernst von Dobschütz, Christusbilder - Untersuchungen Zur Christlichen Legende, Orig. edit. Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs´sche buchhandlung, 1899. New edit. Kessinger Publishing's Legacy Reprints 2009. ISBN 1-120-17642-5

- Emerick, Judson J., The Tempietto Del Clitunno Near Spoleto, 1998, Penn State Press, ISBN 0271044500, 9780271044507, google books

- Grigg, Robert, "Byzantine Credulity as an Impediment to Antiquarianism", Gesta, Vol. 26, No. 1 (1987), pp. 3–9, The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the International Center of Medieval Art, JSTOR

- Kitzinger, Ernst, "The Cult of Images in the Age before Iconoclasm", Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Vol. 8, (1954), pp. 83–150, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, JSTOR

External links

edit- International Workshop on the Scientific Approach to the Acheiropoietos Images

- Translation of the Image "Made-Without-Hands" of our Lord Jesus Christ Orthodox synaxarion

- Icon "Made Without Hands" from Lydda

- Sudarium Christi The Face of Christ online audio visual featuring texts by sudarium expert Sr. Blandina Paschalis Schlömer et al.

- The Rediscovered Face - 1 first of four installments of an audiovisual presentation relating a number of ancient predecessors, YouTube, access date March 2013.