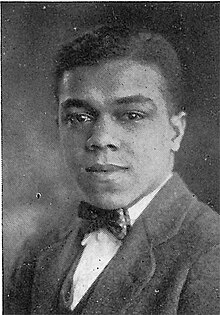

William Jacob Knox Jr. (January 5, 1904 - July 9, 1995) was an American chemist at Columbia University in New York City and one of the African American scientists and technicians on the Manhattan Project.[1] Knox held an unprecedented position, serving as the only African American supervisor for the Manhattan Project. Knox is credited for nuclear research of gaseous diffusion techniques used for the separation of uranium isotopes. Knox's efforts in the development of uranium contributed to the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, in 1945.

William Jacob Knox Jr. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 5, 1904 |

| Died | July 9, 1995 (aged 91) |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Harvard University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemistry |

| Institutions | Columbia University, Manhattan Project |

Knox was highly educated and received his undergraduate degree from Harvard University. Knox then continued his postgraduate studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in New Bedford, Massachusetts. By 1935, the Knox family alone made up 7% of total African Americans to hold a Ph.D.[1]

After the war, Knox became a research assistant at Eastman Kodak Company. Knox is credited as being "the man to consult about coating problems".[2] As Knox ended his career in science, he became involved in activism and additional professional pursuits.

Early life and education edit

Knox was born on January 5, 1904, in New Bedford, Massachusetts, to William Jacob Knox Sr., a US postal worker, and Estella Briggs.[3] William Sr. had a slave heritage as his grandfather, Elijah Knox, was an enslaved carpenter in Edenton, North Carolina. Elijah's eldest child was Harriet Jacobs, the author of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. According to family tradition, William Jacob Sr. was given his middle name "in honor of his aunt Harriet and his uncle John S."[4] The Knox family had a strong "tradition of upward mobility through education".[3]

William was the oldest of 5 children. Knox and his two younger brothers, Clinton Everett and Lawrence "Larry" Howland, all attended Harvard University (as well as other universities). All three earned doctoral degrees, William and Lawrence studying chemistry and Clinton studying history. William entered Harvard as an undergraduate in September 1921 and graduated in 1925.[5] During his time at Harvard, William faced persecution and fought racist discrimination. He was accepted into Harvard University's undergraduate program in 1921. He was told to report to the freshman housing once he arrived for the semester. Upon arriving, Knox was immediately ousted for being black and was forced to give up his room in the whites-only dormitories.[2] This confrontation with the housing at Harvard and many other instances such as realtors only offering an abandoned brothel may have influenced Knox heavily, as he would join the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in Rochester, New York, after his work in the Manhattan Project. William Knox confronted discrimination head-on by receiving further education.

In 1929, Knox began to teach at Howard University, a private university in Washington, D.C. While instructing at Howard, Knox was introduced to his wife, Edna Lenora Jordan. Knox and Jordan were legally wed on September 1, 1931. Together they had one child, Sandra Knox.

Early professional work edit

After obtaining his master's degree in organic chemistry (1929) and Ph.D. in chemical engineering (1935) from MIT,[1] Knox became a professor in the chemistry department at North Carolina A&T College. Knox taught general, analytical, organic, and physical chemistry from 1935 to 1942.[3] In 1942, Knox took a promotion, leaving North Carolina A&T to become the head of the department of chemistry at Talladega College, a historically black institution in Talladega, Alabama.

Manhattan Project edit

In 1943, one year after taking the position of chair of chemistry at Talladega College, Knox joined a team of scientists at Columbia University, known as the Manhattan Project, in New York City (1942–1945).[3] The Manhattan Project consisted of researching teams at Columbia University as well as developing sites for plutonium and uranium at Hanford, Washington, Los Alamos, New Mexico, and Oak Ridge, Tennessee.[6] William's brother Lawrence eventually joined him at Columbia University as a head research analyst for the Manhattan Project in New York City.

The project would be successful, as the United States developed the first atomic weapons in history and brought the end of World War II with the dropping of atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Knox's team researched and innovated the isolation of uranium isotopes using gaseous diffusion. The government compiled several influential and highly educated individuals in the atomic field at Columbia University.[7] The university was awarded with the government's first federal contract to explore the use of atomic power for energy and weapons.[8] Experiments at Columbia University indicated that "uranium might be used as an explosive that would liberate a million times as much energy per pound as any known explosive".[9]

Knox held a position unprecedented at the time, being the only African-American scientist to be a supervisor in the Manhattan Project. Like many scientists involved in the Manhattan Project, Knox and his team were unaware of how vital their research was. The complex process of breaking apart uranium isotopes utilizing uranium hexafluoride was crucial to the development of the atomic bombs used to end war with Japan in 1945. Uranium-235 and plutonium-239 made up the composite core of the atomic weapons.[10] Knox was a section leader in the Corrosion Section before leaving Columbia University at the end of the war.[11]

Post-war activities edit

Eastman Kodak Company edit

In 1945, Knox left his position on Columbia University's nuclear research team at the conclusion of World War II. Knox soon after became a research assistant at Eastman Kodak Company (Kodak) in Rochester, New York, from 1945 to 1970.[12] Knox became the second African American PhD chemist to be hired by the company.[2] At the time, Kodak was leading the world in the development of photographic technology.[13] Knox used his scientific skill set as a catalyst within the private industry sector. Twenty-one patents are recorded in Knox's name during his time with Kodak regarding the "application on surfactants in [the] photogenic process".[11][12] Following his retirement and death, Kodak continues to renew nine of Knox's original patents, which are used to harden photographic emulsions and protect the coating of photographs.[14]

Continued teaching edit

Following his departure from Kodak, William Knox returned to North Carolina A&T University, to teach chemistry, before permanently retiring in 1973.[11][15]

Death edit

William Jacob Knox died on July 9, 1995, after a battle with prostate cancer.[15] Knox died in Newton, Massachusetts, at the age of 91.

Impact and legacy edit

Knox clearly cared for his community and fought for social justice, having faced discrimination throughout his life and being an active member of his local chapter of the NAACP. As Knox searched for housing near his daughter's schooling, he was unable. A coworker recognized his struggles and bought a lot under his name, which he then sold to Knox. This prompted Knox to get involved in fighting against housing injustices and for basic civil rights.[5] Knox was a founding member of the Urban League of Rochester. As a response to civil unrest in 1965, the League was established to "Enable African-Americans, Latinos, the poor and other disadvantaged to secure economic self-reliance, parity and power and civil rights".[16] The league, being a local chapter of the National Urban League, provides over 30 programs for individuals that are struggling in any aspect of life. The league also gives out scholarships to minority students, of which Knox was a donor for.[11] Today, the Urban League of Rochester serves over 4,000 individuals. Knox, being a founding member of the Urban League of Rochester, showed that he not only fought against social injustice but also strove to better his community as well.

References edit

- ^ a b c Gortler, Leon; Weininger, Stephen J. (July 2, 2010). "Chemical Relations: William and Lawrence Knox, African American Chemists". Science History Institute.

- ^ a b c "William J. Knox, Jr., Ca. 1925." MIT Black History, www.blackhistory.mit.edu/archive/william-j-knox-jr-ca-1925

- ^ a b c d Burrell, Shannon, and Laura Thompson. "Knox, William J. Jr." Amistad Research Center, amistadresearchcenter.tulane.edu/archon/?p=creators/creator&id=404

- ^ Yellin, Jean Fagan (2004). Harriet Jacobs: A Life. New York: Basic Civitas Books. p. 224. ISBN 0-465-09288-8.

In 1875, however, a second son was born, and family tradition holds that little William Jacob received his middle name in honor of his aunt Harriet and his uncle John S., who were using Jacobs, the name that their [enslaved] father had been denied.

- ^ a b Lester, Paul. "Black History Month: Dr. William Jacob Knox Jr." ENERGY.GOV, January 28, 2019, www.energy.gov/articles/black-history-month-5-facts-about-dr-william-jacob-knox-jr

- ^ S. A. Larson, "The Manhattan Project [History]." IEEE Industry Applications, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 7-13, 2013, https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/6461516

- ^ "Giant Cyclotron To Be Built At Columbia University." Science News-Letter, vol. 50, no. 25, December 21, 1946, pp. 196–196. JSTOR 25172026

- ^ "Research Guides: Columbia University Archives: Manhattan Project." Manhattan Project - Columbia University Archives - Research Guides at Columbia University. Accessed November 6, 2020. https://guides.library.columbia.edu/uarchives/manhattanproject.

- ^ Lippsett, Laurence. "The Manhattan Project: Columbia's Wartime Secret." Columbia College Today, 1995. https://guides.library.columbia.edu/ld.php?content_id=31583434.

- ^ Reed, B. Cameron. "Composite Cores and Tamper Yield: Lesser-Known Aspects of Manhattan Project Fission Bombs." American Journal of Physics, American Association of Physics. aapt-scitation-org.erl.lib.byu.edu/doi/full/10.1119/10.0000035.

- ^ a b c d "William Jacob Knox." Atomic Heritage Foundation, 2019, www.atomicheritage.org/profile/william-jacob-knox

- ^ a b Sluby, Patricia Carter. "The Inventive Spirit of African Americans" Patented Ingenuity. United Kingdom, Praeger, 2004.

- ^ "Photography History." Kodak, www.kodak.com/en/company/page/photography-history

- ^ "US3506449A - Gelatin Coating Compositions with n-Tallow-Beta-Iminodipropionic Acid." Google Patents. Google. Accessed November 17, 2020. https://patents.google.com/patent/US3506449

- ^ a b Absher, A. "William Jacob Knox Jr. (1904-1995), August 2, 2019. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/knox-william-jacob-jr-1904-1995/

- ^ "Urban League of Rochester." Urban League of Rochester, New York > About Us, Urban League of Rochester, 2014, www.ulr.org/AboutUs.aspx