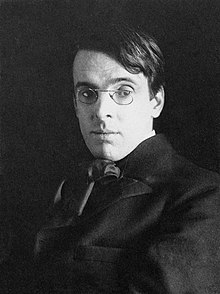

William Butler Yeats[a] (13 June 1865 – 28 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist and writer, and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival, and along with Lady Gregory founded the Abbey Theatre, serving as its chief during its early years. He was awarded the 1923 Nobel Prize in Literature, and later served two terms as a Senator of the Irish Free State.

A Protestant of Anglo-Irish descent, Yeats was born in Sandymount, Ireland. His father practised law and was a successful portrait painter. He was educated in Dublin and London and spent his childhood holidays in County Sligo. He studied poetry from an early age, when he became fascinated by Irish legends and the occult. While in London he became part of the Irish literary revival. His early poetry was influenced by John Keats, William Wordsworth, William Blake and many more. These topics feature in the first phase of his work, lasting roughly from his student days at the Metropolitan School of Art in Dublin until the turn of the century. His earliest volume of verse was published in 1889, and its slow-paced, modernist and lyrical poems display debts to Edmund Spenser, Percy Bysshe Shelley and the poets of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

From 1900 his poetry grew more physical, realistic and politicised. He moved away from the transcendental beliefs of his youth, though he remained preoccupied with some elements including cyclical theories of life. He had become the chief playwright for the Irish Literary Theatre in 1897, and early on promoted younger poets such as Ezra Pound. His major works include The Land of Heart's Desire (1894), Cathleen ni Houlihan (1902), Deirdre (1907), The Wild Swans at Coole (1919), The Tower (1928) and Last Poems and Plays (1940).

Biography

editEarly years

editWilliam Butler Yeats was born in Sandymount in County Dublin, Ireland.[1] His father, John Butler Yeats, was a descendant of Jervis Yeats, a Williamite soldier, linen merchant, and well-known painter, who died in 1712.[2] Benjamin Yeats, Jervis's grandson and William's great-great-grandfather, had in 1773[3] married Mary Butler[4] of a landed family in County Kildare.[5] Following their marriage, they kept the name Butler. Mary was of the Butler of Neigham (pronounced Nyam[needs IPA]) Gowran family, descended from an illegitimate brother of The 8th Earl of Ormond.[6]

At the time of his marriage, his father, John, was studying law but later pursued art studies at Heatherley School of Fine Art, in London.[7] William's mother, Susan Mary Pollexfen, from Sligo, came from a wealthy merchant family, who owned a milling and shipping business. Soon after William's birth, the family relocated to the Pollexfen home at Merville, Sligo, to stay with her extended family, and the young poet came to think of the area as his childhood and spiritual home. Its landscape became, over time, both personally and symbolically, his "country of the heart".[8] So too did its location by the sea; John Yeats stated that "by marriage with a Pollexfen, we have given a tongue to the sea cliffs".[9] The Butler Yeats family were highly artistic; his brother Jack became an esteemed painter, while his sisters Elizabeth and Susan Mary—known to family and friends as Lollie and Lily—became involved in the Arts and Crafts movement.[10] Their cousin Ruth Pollexfen, who was raised by the Yeats sisters after her parents' separation, designed the interior of the Australian prime minister's official residence.[11]

Yeats was raised a member of the Protestant Ascendancy, which was at the time undergoing a crisis of identity. While his family was supportive of the changes Ireland was experiencing, the nationalist revival of the late 19th century directly disadvantaged his heritage and informed his outlook for the remainder of his life. In 1997, his biographer R. F. Foster observed that Napoleon's dictum that to understand the man you have to know what was happening in the world when he was twenty "is manifestly true of W.B.Y."[12] Yeats's childhood and young adulthood were shadowed by the power-shift away from the minority Protestant Ascendancy. The 1880s saw the rise of Charles Stewart Parnell and the home rule movement; the 1890s saw the momentum of nationalism, while the Irish Catholics became prominent around the turn of the century. These developments had a profound effect on his poetry, and his subsequent explorations of Irish identity had a significant influence on the creation of his country's biography.[13]

In 1867, the family moved to England to aid their father, John, to further his career as an artist. At first, the Yeats children were educated at home. Their mother entertained them with stories and Irish folktales. John provided an erratic education in geography and chemistry and took William on natural history explorations of the nearby Slough countryside.[14] On 26 January 1877, the young poet entered the Godolphin School,[15] which he attended for four years. He did not distinguish himself academically, and an early school report describes his performance as "only fair. Perhaps better in Latin than in any other subject. Very poor in spelling".[16] Though he had difficulty with mathematics and languages (possibly because he was tone deaf[17] and had dyslexia[18]), he was fascinated by biology and zoology. In 1879 the family moved to Bedford Park taking a two-year lease at 8 Woodstock Road.[19] For financial reasons, the family returned to Dublin toward the end of 1880, living at first in the suburbs of Harold's Cross[20] and later in Howth. In October 1881, Yeats resumed his education at Dublin's Erasmus Smith High School.[21] His father's studio was nearby and William spent a great deal of time there, where he met many of the city's artists and writers. During this period he started writing poetry, and, in 1885, the Dublin University Review published Yeats's first poems, as well as an essay entitled "The Poetry of Sir Samuel Ferguson". Between 1884 and 1886, William attended the Metropolitan School of Art—now the National College of Art and Design—in Thomas Street.[1] In March 1888 the family moved to 3 Blenheim Road in Bedford Park [22] where they would remain until 1902.[19] The rent on the house in 1888 was £50 a year.[19]

He began writing his first works when he was seventeen; these included a poem—heavily influenced by Percy Bysshe Shelley—that describes a magician who set up a throne in central Asia. Other pieces from this period include a draft of a play about a bishop, a monk, and a woman accused of paganism by local shepherds, as well as love-poems and narrative lyrics on German knights. The early works were both conventional and, according to the critic Charles Johnston, "utterly unIrish", seeming to come out of a "vast murmurous gloom of dreams".[23] Although Yeats's early works drew heavily on Shelley, Edmund Spenser, and on the diction and colouring of pre-Raphaelite verse, he soon turned to Irish mythology and folklore and the writings of William Blake. In later life, Yeats paid tribute to Blake by describing him as one of the "great artificers of God who uttered great truths to a little clan".[24] In 1891, Yeats published John Sherman and "Dhoya", one a novella, the other a story. The influence of Oscar Wilde is evident in Yeats's theory of aesthetics, especially in his stage plays, and runs like a motif through his early works.[25] The theory of masks, developed by Wilde in his polemic The Decay of Lying can clearly be seen in Yeats's play The Player Queen,[26] while the more sensual characterisation of Salomé, in Wilde's play of the same name, provides the template for the changes Yeats made in his later plays, especially in On Baile's Strand (1904), Deirdre (1907), and his dance play The King of the Great Clock Tower (1934).[27]

Young poet

editThe family returned to London in 1887. In March 1890 Yeats joined the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, and with Ernest Rhys co-founded the Rhymers' Club,[28] a group of London-based poets who met regularly in a Fleet Street tavern to recite their verse. Yeats later sought to mythologize the collective, calling it the "Tragic Generation" in his autobiography,[29] and published two anthologies of the Rhymers' work, the first one in 1892 and the second one in 1894. He collaborated with Edwin Ellis on the first complete edition of William Blake's works, in the process rediscovering a forgotten poem, "Vala, or, the Four Zoas".[30][31]

Yeats had a lifelong interest in mysticism, spiritualism, occultism and astrology. He read extensively on the subjects throughout his life, became a member of the paranormal research organisation "The Ghost Club" (in 1911) and was influenced by the writings of Emanuel Swedenborg.[32] As early as 1892, he wrote: "If I had not made magic my constant study I could not have written a single word of my Blake book, nor would The Countess Kathleen ever have come to exist. The mystical life is the centre of all that I do and all that I think and all that I write."[33] His mystical interests—also inspired by a study of Hinduism, under the Theosophist Mohini Chatterjee, and the occult—formed much of the basis of his late poetry. Some critics disparaged this aspect of Yeats's work.[34]

His first significant poem was "The Island of Statues", a fantasy work that took Edmund Spenser and Shelley for its poetic models. The piece was serialized in the Dublin University Review. Yeats wished to include it in his first collection, but it was deemed too long, and in fact, was never republished in his lifetime. Quinx Books published the poem in complete form for the first time in 2014. His first solo publication was the pamphlet Mosada: A Dramatic Poem (1886), which comprised a print run of 100 copies paid for by his father. This was followed by the collection The Wanderings of Oisin and Other Poems (1889), which arranged a series of verse that dated as far back as the mid-1880s. The long title poem contains, in the words of his biographer R. F. Foster, "obscure Gaelic names, striking repetitions [and] an unremitting rhythm subtly varied as the poem proceeded through its three sections":[35]

We rode in sorrow, with strong hounds three,

Bran, Sceolan, and Lomair,

On a morning misty and mild and fair.

The mist-drops hung on the fragrant trees,

And in the blossoms hung the bees.

We rode in sadness above Lough Lean,

For our best were dead on Gavra's green.

"The Wanderings of Oisin" is based on the lyrics of the Fenian Cycle of Irish mythology and displays the influence of both Sir Samuel Ferguson and the Pre-Raphaelite poets.[36] The poem took two years to complete and was one of the few works from this period that he did not disown in his maturity. Oisin introduces what was to become one of his most important themes: the appeal of the life of contemplation over the appeal of the life of action. Following the work, Yeats never again attempted another long poem. His other early poems, which are meditations on the themes of love or mystical and esoteric subjects, include Poems (1895), The Secret Rose (1897), and The Wind Among the Reeds (1899). The covers of these volumes were illustrated by Yeats's friend Althea Gyles.[37]

During 1885, Yeats was involved in the formation of the Dublin Hermetic Order. That year the Dublin Theosophical lodge was opened in conjunction with Brahmin Mohini Chatterjee, who travelled from the Theosophical Society in London to lecture. Yeats attended his first séance the following year. He later became heavily involved with the Theosophy and with hermeticism, particularly with the eclectic Rosicrucianism of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. During séances held from 1912, a spirit calling itself "Leo Africanus" apparently claimed it was Yeats's Daemon or anti-self, inspiring some of the speculations in Per Amica Silentia Lunae.[38] He was admitted into the Golden Dawn in March 1890 and took the magical motto Daemon est Deus inversus—translated as 'Devil is God inverted'.[b] He was an active recruiter for the sect's Isis-Urania Temple, and brought in his uncle George Pollexfen, Maud Gonne, and Florence Farr. Although he reserved a distaste for abstract and dogmatic religions founded around personality cults, he was attracted to the type of people he met at the Golden Dawn.[39] He was involved in the Order's power struggles, both with Farr and Macgregor Mathers, and was involved when Mathers sent Aleister Crowley to repossess Golden Dawn paraphernalia during the "Battle of Blythe Road". After the Golden Dawn ceased and splintered into various offshoots, Yeats remained with the Stella Matutina until 1921.[40]

Maud Gonne

editIn 1889, Yeats met Maud Gonne, a 23-year-old English heiress and ardent Irish nationalist.[c] She was eighteen months younger than Yeats and later claimed she met the poet as a "paint-stained art student."[41] Gonne admired "The Island of Statues" and sought out his acquaintance. Yeats began an obsessive infatuation, and she had a significant and lasting effect on his poetry and his life thereafter.[42] In later years he admitted, "it seems to me that she [Gonne] brought into my life those days—for as yet I saw only what lay upon the surface—the middle of the tint, a sound as of a Burmese gong, an over-powering tumult that had yet many pleasant secondary notes."[43] Yeats's love was unrequited, in part due to his reluctance to participate in her nationalist activism.[44]

In 1891 he visited Gonne in Ireland and proposed marriage, but was rejected. He later admitted that from that point "the troubling of my life began".[45] Yeats proposed to Gonne three more times: in 1899, 1900 and 1901. She refused each proposal, and in 1903, to his dismay, married the Irish nationalist Major John MacBride.[46] His only other love affair during this period was with Olivia Shakespear, whom he first met in 1894, and parted from in 1897.

Yeats derided MacBride in letters and in poetry. He was horrified by Gonne's marriage, at losing his muse to another man; in addition, her conversion to Catholicism before marriage offended him; Yeats was Protestant/agnostic. He worried his muse would come under the influence of the priests and do their bidding.[47]

Gonne's marriage to MacBride was a disaster. This pleased Yeats, as Gonne began to visit him in London. After the birth of her son, Seán MacBride, in 1904, Gonne and MacBride agreed to end the marriage, although they were unable to agree on the child's welfare. Despite the use of intermediaries, a divorce case ensued in Paris in 1905. Gonne made a series of allegations against her husband with Yeats as her main 'second', though he did not attend court or travel to France. A divorce was not granted, for the only accusation that held up in court was that MacBride had been drunk once during the marriage. A separation was granted, with Gonne having custody of the baby and MacBride having visiting rights.[48]

In 1895, Yeats moved into number 5 Woburn Walk and resided there until 1919.[49]

Yeats's friendship with Gonne ended, yet, in Paris in 1908, they finally consummated their relationship. "The long years of fidelity rewarded at last" was how another of his lovers described the event. Yeats was less sentimental and later remarked that "the tragedy of sexual intercourse is the perpetual virginity of the soul."[45] The relationship did not develop into a new phase after their night together, and soon afterwards Gonne wrote to the poet indicating that despite the physical consummation, they could not continue as they had been: "I have prayed so hard to have all earthly desire taken from my love for you and dearest, loving you as I do, I have prayed and I am praying still that the bodily desire for me may be taken from you too."[50] By January 1909, Gonne was sending Yeats letters praising the advantage given to artists who abstain from sex. Nearly twenty years later, Yeats recalled the night with Gonne in his poem "A Man Young and Old":[51]

My arms are like the twisted thorn

And yet there beauty lay;

The first of all the tribe lay there

And did such pleasure take;

She who had brought great Hector down

And put all Troy to wreck.

In 1896, Yeats was introduced to Lady Gregory by their mutual friend Edward Martyn. Gregory encouraged Yeats's nationalism and convinced him to continue focusing on writing drama. Although he was influenced by French Symbolism, Yeats concentrated on an identifiably Irish content and this inclination was reinforced by his involvement with a new generation of younger and emerging Irish authors. Together with Lady Gregory, Martyn, and other writers including J. M. Synge, Seán O'Casey, and Padraic Colum, Yeats was one of those responsible for the establishment of the "Irish Literary Revival" movement.[52] Apart from these creative writers, much of the impetus for the Revival came from the work of scholarly translators who were aiding in the discovery of both the ancient sagas and Ossianic poetry and the more recent folk song tradition in Irish. One of the most significant of these was Douglas Hyde, later the first President of Ireland, whose Love Songs of Connacht was widely admired.

Abbey Theatre

editIn 1899, Yeats, Lady Gregory, Edward Martyn and George Moore founded the Irish Literary Theatre to promote Irish plays.[53] The ideals of the Abbey were derived from the avant-garde French theatre, which sought to express the "ascendancy of the playwright rather than the actor-manager à l'anglais."[54][55] The group's manifesto, which Yeats wrote, declared, "We hope to find in Ireland an uncorrupted & imaginative audience trained to listen by its passion for oratory ... & that freedom to experiment which is not found in the theatres of England, & without which no new movement in art or literature can succeed."[56] Yeats's interest in the classics and his defiance of English censorship were also fueled by a tour of America he took between 1903 and 1904. Stopping to deliver a lecture at the University of Notre Dame, he learned about the student production of the Oedipus Rex.[57] This play was banned in England, an act he viewed as hypocritical as denounced as part of 'British Puritanism'.[58] He contrasted this with the artistic freedom of the Catholicism found at Notre Dame, which had allowed such a play with themes such as incest and parricide.[58] He desired to stage a production of the Oedipus Rex in Dublin.[57][58]

The collective survived for about two years but was unsuccessful. Working with the Irish brothers with theatrical experience, William and Frank Fay, Yeats's unpaid but independently wealthy secretary Annie Horniman, and the leading West End actress Florence Farr, the group established the Irish National Theatre Society. Along with Synge, they acquired property in Dublin and on 27 December 1904 opened the Abbey Theatre. Yeats's play Cathleen ni Houlihan and Lady Gregory's Spreading the News were featured on the opening night. Yeats remained involved with the Abbey until his death, both as a member of the board and a prolific playwright. In 1902, he helped set up the Dun Emer Press to publish work by writers associated with the Revival. This became the Cuala Press in 1904, and inspired by the Arts and Crafts Movement, sought to "find work for Irish hands in the making of beautiful things."[59] From then until its closure in 1946, the press—which was run by the poet's sisters—produced over 70 titles; 48 of them books by Yeats himself.

Yeats met the American poet Ezra Pound in 1909. Pound had travelled to London at least partly to meet the older man, whom he considered "the only poet worthy of serious study."[60] From 1913 until 1916, the two men wintered in the Stone Cottage at Ashdown Forest, with Pound nominally acting as Yeats's secretary. The relationship got off to a rocky start when Pound arranged for the publication in the magazine Poetry of some of Yeats's verse with Pound's own unauthorised alterations. These changes reflected Pound's distaste for Victorian prosody. A more indirect influence was the scholarship on Japanese Noh plays that Pound had obtained from Ernest Fenollosa's widow, which provided Yeats with a model for the aristocratic drama he intended to write. The first of his plays modelled on Noh was At the Hawk's Well, the first draft of which he dictated to Pound in January 1916.[61]

The emergence of a nationalist revolutionary movement from the ranks of the mostly Roman Catholic lower-middle and working class made Yeats reassess some of his attitudes. In the refrain of "Easter, 1916" ("All changed, changed utterly / A terrible beauty is born"), Yeats faces his own failure to recognise the merits of the leaders of the Easter Rising, due to his attitude towards their ordinary backgrounds and lives.[62] Yeats was close to Lady Gregory and her home place of Coole Park, County Galway. He would often visit and stay there as it was a central meeting place for people who supported the resurgence of Irish literature and cultural traditions. His poem, "The Wild Swans at Coole" was written there, between 1916 and 1917.

He wrote prefaces for two books of Irish mythological tales, compiled by Lady Gregory: Cuchulain of Muirthemne (1902), and Gods and Fighting Men (1904). In the preface of the latter, he wrote: "One must not expect in these stories the epic lineaments, the many incidents, woven into one great event of, let us say the War for the Brown Bull of Cuailgne or that of the last gathering at Muirthemne."[63]

Politics

editYeats was an Irish nationalist, who sought a kind of traditional lifestyle articulated through poems such as 'The Fisherman'. But as his life progressed, he sheltered much of his revolutionary spirit and distanced himself from the intense political landscape until 1922, when he was appointed Senator for the Irish Free State.[64][65]

In the earlier part of his life, Yeats was a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood.[66] In the 1930s, Yeats was fascinated with the authoritarian, anti-democratic, nationalist movements of Europe, and he composed several marching songs for the Blueshirts, although they were never used. He was a fierce opponent of individualism and political liberalism and saw the fascist movements as a triumph of public order and the needs of the national collective over petty individualism. He was an elitist who abhorred the idea of mob-rule, and saw democracy as a threat to good governance and public order.[67] After the Blueshirt movement began to falter in Ireland, he distanced himself somewhat from his previous views, but maintained a preference for authoritarian and nationalist leadership.[68]

Marriage to Georgie Hyde-Lees

editBy 1916, Yeats was 51 years old and determined to marry and produce an heir. His rival, John MacBride, had been executed for his role in the 1916 Easter Rising, so Yeats hoped that his widow, Maud Gonne, might remarry.[69] His final proposal to Gonne took place in mid-1916.[70] Gonne's history of revolutionary political activism, as well as a series of personal catastrophes in the previous few years of her life—including chloroform addiction and her troubled marriage to MacBride—made her a potentially unsuitable wife;[45] biographer R. F. Foster has observed that Yeats's last offer was motivated more by a sense of duty than by a genuine desire to marry her.

Yeats proposed in an indifferent manner, with conditions attached, and he both expected and hoped she would turn him down. According to Foster, "when he duly asked Maud to marry him and was duly refused, his thoughts shifted with surprising speed to her daughter." Iseult Gonne was Maud's second child with Lucien Millevoye, and at the time was twenty-one years old. She had lived a sad life to this point; conceived as an attempt to reincarnate her short-lived brother, for the first few years of her life she was presented as her mother's adopted niece. When Maud told her that she was going to marry, Iseult cried and told her mother that she hated MacBride.[71] When Gonne took action to divorce MacBride in 1905, the court heard allegations that he had sexually assaulted Iseult, then eleven. At fifteen, she proposed to Yeats. In 1917, he proposed to Iseult but was rejected.

That September, Yeats proposed to 25-year-old Georgie Hyde-Lees (1892–1968), known as George, whom he had met through Olivia Shakespear. Despite warnings from her friends—"George ... you can't. He must be dead"—Hyde-Lees accepted, and the two were married on 20 October 1917.[45] Their marriage was a success, in spite of the age difference, and in spite of Yeats's feelings of remorse and regret during their honeymoon. The couple went on to have two children, Anne and Michael. Although in later years he had romantic relationships with other women, Georgie herself wrote to her husband "When you are dead, people will talk about your love affairs, but I shall say nothing, for I will remember how proud you were."[72]

During the first years of marriage, they experimented with automatic writing; she contacted a variety of spirits and guides they called "Instructors" while in a trance. The spirits communicated a complex and esoteric system of philosophy and history, which the couple developed into an exposition using geometrical shapes: phases, cones, and gyres.[73] Yeats devoted much time to preparing this material for publication as A Vision (1925). In 1924, he wrote to his publisher T. Werner Laurie, admitting: "I dare say I delude myself in thinking this book my book of books".[74]

Nobel Prize

editIn December 1923, Yeats was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature "for his always inspired poetry, which in a highly artistic form gives expression to the spirit of a whole nation".[75] Politically aware, he knew the symbolic value of an Irish winner so soon after Ireland had gained independence, and highlighted the fact at each available opportunity. His reply to many of the letters of congratulations sent to him contained the words: "I consider that this honour has come to me less as an individual than as a representative of Irish literature, it is part of Europe's welcome to the Free State."[76]

Yeats used the occasion of his acceptance lecture at the Royal Academy of Sweden to present himself as a standard-bearer of Irish nationalism and Irish cultural independence. As he remarked, "The theatres of Dublin were empty buildings hired by the English travelling companies, and we wanted Irish plays and Irish players. When we thought of these plays we thought of everything that was romantic and poetical because the nationalism we had called up—the nationalism every generation had called up in moments of discouragement—was romantic and poetical."[77] The prize led to a significant increase in the sales of his books, as his publishers Macmillan sought to capitalise on the publicity. For the first time he had money, and he was able to repay not only his own debts but those of his father.[78]

Old age and death

editBy early 1925, Yeats's health had stabilised, and he had completed most of the writing for A Vision (dated 1925, it actually appeared in January 1926, when he almost immediately started rewriting it for a second version). He had been appointed to the first Irish Senate in 1922, and was re-appointed for a second term in 1925.[79][80] Early in his tenure, a debate on divorce arose, and Yeats viewed the issue as primarily a confrontation between the emerging Roman Catholic ethos and the Protestant minority.[81] When the Roman Catholic Church weighed in with a blanket refusal to consider their anti position, The Irish Times countered that a measure to outlaw divorce would alienate Protestants and "crystallise" the partition of Ireland. In response, Yeats delivered a series of speeches that attacked the "quixotically impressive" ambitions of the government and clergy, likening their campaign tactics to those of "medieval Spain."[82] "Marriage is not to us a Sacrament, but, upon the other hand, the love of a man and woman, and the inseparable physical desire, are sacred. This conviction has come to us through ancient philosophy and modern literature, and it seems to us a most sacrilegious thing to persuade two people who hate each other... to live together, and it is to us no remedy to permit them to part if neither can re-marry."[82] The resulting debate has been described as one of Yeats's "supreme public moments", and began his ideological move away from pluralism towards religious confrontation.[83]

His language became more forceful; the Jesuit Father Peter Finlay was described by Yeats as a man of "monstrous discourtesy", and he lamented that "It is one of the glories of the Church in which I was born that we have put our Bishops in their place in discussions requiring legislation".[82] During his time in the Senate, Yeats further warned his colleagues: "If you show that this country, southern Ireland, is going to be governed by Roman Catholic ideas and by Catholic ideas alone, you will never get the North... You will put a wedge in the midst of this nation".[84] He memorably said of his fellow Irish Protestants, "we are no petty people".

In 1924 he chaired a coinage committee charged with selecting a set of designs for the first currency of the Irish Free State. Aware of the symbolic power latent in the imagery of a young state's currency, he sought a form that was "elegant, racy of the soil, and utterly unpolitical".[85] When the house finally decided on the artwork of Percy Metcalfe, Yeats was pleased, though he regretted that compromise had led to "lost muscular tension" in the finally depicted images.[85] He retired from the Senate in 1928 because of ill health.[86]

Towards the end of his life—and especially after the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and Great Depression, which led some to question whether democracy could cope with deep economic difficulty—Yeats seems to have returned to his aristocratic sympathies. During the aftermath of the First World War, he became sceptical about the efficacy of democratic government, and anticipated political reconstruction in Europe through totalitarian rule.[87] His later association with Pound drew him towards Benito Mussolini, for whom he expressed admiration on a number of occasions.[77] He wrote three "marching songs"—never used—for the Irish General Eoin O'Duffy's Blueshirts.

At the age of 69 he was 'rejuvenated' by the Steinach operation which was performed on 6 April 1934 by Norman Haire.[88] For the last five years of his life Yeats found a new vigour evident from both his poetry and his intimate relations with younger women.[89] During this time, Yeats was involved in a number of romantic affairs with, among others, the poet and actress Margot Ruddock, and the novelist, journalist and sexual radical Ethel Mannin.[90] As in his earlier life, Yeats found erotic adventure conducive to his creative energy, and, despite age and ill-health, he remained a prolific writer. In a letter of 1935, Yeats noted: "I find my present weakness made worse by the strange second puberty the operation has given me, the ferment that has come upon my imagination. If I write poetry it will be unlike anything I have done".[91] In 1936, he undertook editorship of the Oxford Book of Modern Verse, 1892–1935.[46] From 1935 to 1936 he travelled to the Western Mediterranean island of Majorca with Indian-born Shri Purohit Swami and from there the two of them performed the majority of the work in translating the principal Upanishads from Sanskrit into common English; the resulting work, The Ten Principal Upanishads, was published in 1938.[92]

He died at the Hôtel Idéal Beauséjour in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, near Menton, France, on 28 January 1939, aged 73.[93] He was buried after a discreet and private funeral at Roquebrune. Attempts had been made at Roquebrune to dissuade the family from proceeding with the removal of the remains to Ireland due to the uncertainty of their identity. His body had earlier been exhumed and transferred to the ossuary.[94] Yeats and George had often discussed his death, and his express wish was that he be buried quickly in France with a minimum of fuss. According to George, "His actual words were 'If I die, bury me up there [at Roquebrune] and then in a year's time when the newspapers have forgotten me, dig me up and plant me in Sligo'."[95] In September 1948, Yeats's body was moved to the churchyard of St Columba's Church, Drumcliff, County Sligo, on the Irish Naval Service corvette LÉ Macha.[96] The person in charge of this operation for the Irish Government was Seán MacBride, son of Maud Gonne MacBride, and then Minister of External Affairs.[97]

His epitaph is taken from the last lines of "Under Ben Bulben",[98] one of his final poems:

Cast a cold Eye

On Life, on Death.

Horseman, pass by!

The French ambassador Stanislas Ostroróg was involved in returning Yeats' remains to Ireland in 1948; in a letter to the European director of the Foreign Ministry in Paris, "Ostrorog tells how Yeats's son Michael sought official help in locating the poet's remains. Neither Michael Yeats nor Sean MacBride, the Irish foreign minister who organised the ceremony, wanted to know the details of how the remains were collected, Ostrorog notes. He repeatedly urges caution and discretion and says the Irish ambassador in Paris should not be informed." Yeats's body was exhumed in 1946 and the remains were moved to an ossuary and mixed with other remains. The French Foreign Ministry authorized Ostrorog to secretly cover the cost of repatriation from his slush fund. Authorities were worried about the fact that the much-loved poet's remains were thrown into a communal grave, causing embarrassment for both Ireland and France. Per a letter from Ostroróg to his superiors, "Mr Rebouillat, (a) forensic doctor in Roquebrune would be able to reconstitute a skeleton presenting all the characteristics of the deceased."[99]

Style

editYeats is considered one of the key 20th-century English-language poets. He was a Symbolist poet, using allusive imagery and symbolic structures throughout his career. He chose words and assembled them so that, in addition to a particular meaning, they suggest abstract thoughts that may seem more significant and resonant. His use of symbols[100] is usually something physical that is both itself and a suggestion of other, perhaps immaterial, timeless qualities.[101]

Unlike the modernists who experimented with free verse, Yeats was a master of the traditional forms.[102] The impact of modernism on his work can be seen in the increasing abandonment of the more conventionally poetic diction of his early work in favour of the more austere language and more direct approach to his themes that increasingly characterises the poetry and plays of his middle period, comprising the volumes In the Seven Woods, Responsibilities and The Green Helmet.[103] His later poetry and plays are written in a more personal vein, and the works written in the last twenty years of his life include mention of his son and daughter,[104] as well as meditations on the experience of growing old.[105] In his poem "The Circus Animals' Desertion", he describes the inspiration for these late works:

Now that my ladder's gone

I must lie down where all the ladders start

In the foul rag and bone shop of the heart.[106]

During 1929, he stayed at Thoor Ballylee near Gort in County Galway (where Yeats had his summer home since 1919) for the last time. Much of the remainder of his life was lived outside Ireland, although he did lease Riversdale house in the Dublin suburb of Rathfarnham in 1932. He wrote prolifically through his final years, and published poetry, plays, and prose. In 1938, he attended the Abbey for the final time to see the premiere of his play Purgatory. His Autobiographies of William Butler Yeats was published that same year.[107] The preface for the English translation of Rabindranath Tagore's Gitanjali (Song Offering) (for which Tagore won the Nobel prize in Literature) was written by Yeats in 1913.[108]

While Yeats's early poetry drew heavily on Irish myth and folklore, his later work was engaged with more contemporary issues, and his style underwent a dramatic transformation. His work can be divided into three general periods. The early poems are lushly pre-Raphaelite in tone, self-consciously ornate, and, at times, according to unsympathetic critics, stilted. Yeats began by writing epic poems such as The Isle of Statues and The Wanderings of Oisin.[109] His other early poems are lyrics on the themes of love or mystical and esoteric subjects. Yeats's middle period saw him abandon the pre-Raphaelite character of his early work[110] and attempt to turn himself into a Landor-style social ironist.[111]

Critics characterize his middle work as supple and muscular in its rhythms and sometimes harshly modernist, while others find the poems barren and weak in imaginative power. Yeats's later work found new imaginative inspiration in the mystical system he began to work out for himself under the influence of spiritualism. In many ways, this poetry is a return to the vision of his earlier work. The opposition between the worldly-minded man of the sword and the spiritually minded man of God, the theme of The Wanderings of Oisin, is reproduced in A Dialogue Between Self and Soul.[112]

Some critics hold that Yeats spanned the transition from the 19th century into 20th-century modernism in poetry much as Pablo Picasso did in painting; others question whether late Yeats has much in common with modernists of the Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot variety.[113]

Modernists read the well-known poem "The Second Coming" as a dirge for the decline of European civilisation, but it also expresses Yeats's apocalyptic mystical theories and is shaped by the 1890s. His most important collections of poetry started with The Green Helmet (1910) and Responsibilities (1914). In imagery, Yeats's poetry became sparer and more powerful as he grew older. The Tower (1928), The Winding Stair (1933), and New Poems (1938) contained some of the most potent images in 20th-century poetry.[114]

Yeats's mystical inclinations, informed by Hinduism, theosophical beliefs and the occult, provided much of the basis of his late poetry,[115] which some critics have judged as lacking in intellectual credibility. The metaphysics of Yeats's late works must be read in relation to his system of esoteric fundamentals in A Vision (1925).[116]

Legacy

editYeats is commemorated in Sligo town by a statue, sculpted by Rowan Gillespie in 1989. On the 50th anniversary of the poet's death, it was erected outside the Ulster Bank. When receiving his Nobel Prize in Stockholm, Yeats had remarked on the similarities between that city's Royal Palace and the Ulster Bank. Across the river is the Yeats Memorial Building, which houses the Sligo Yeats Society.[117] Standing Figure: Knife Edge by Henry Moore is displayed in the W. B. Yeats Memorial Garden at St Stephen's Green in Dublin.[118][119]

Composer Marcus Paus' choral work The Stolen Child (2009) is based on poetry by Yeats. Critic Stephen Eddins described it as "sumptuously lyrical and magically wild, and [...] beautifully [capturing] the alluring mystery and danger and melancholy" of Yeats.[120] Argentine composer Julia Stilman-Lasansky based her Cantata No. 4 on text by Yeats.[121]

There is a blue plaque dedicated to Yeats at Balscadden House on the Balscadden Road in Howth; his cottage home from 1880-1883.[122] In 1957 the London County Council erected a plaque at his former residence on 23 Fitzroy Road, Primrose Hill, London.[123]

Notes

edit- ^ Pronounced /jeɪts/

- ^ Daemon est Deus inversus—is taken from the writings of Madame Blavatsky in which she claimed that "... even that divine Homogeneity must contain in itself the essence of both good and evil", and uses the motto as a symbol of the astral plane's light.

- ^ Gonne claimed they first met in London three years earlier. Foster notes how Gonne was "notoriously unreliable on dates and places (1997, p. 57).

References

edit- ^ a b Obituary. "W. B. Yeats Dead Archived 28 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine". The New York Times, 30 January 1939. Retrieved on 21 May 2007.

- ^ Jeffares, A. Norman. W. B. Yeats, Man and Poet. Palgrave Macmillan, 1996. 1

- ^ Conner, Lester I.; Conner, Lester I. (2 May 1998). A Yeats Dictionary: Persons and Places in the Poetry of William Butler Yeats. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-2770-8. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Limerick Chronicle, 13 August 1763

- ^ Margaret M. Phelan. "Journal of the Butler Society 1982. Gowran, its connection with the Butler Family". p. 174. Archived from the original on 26 February 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ Old Kilkenny Review, The Journal of the Kilkenny Archaeological Society, vol. 2, no. 1, 1979, p. 71

- ^ "Ricorso: Digital materials for the study and appreciation of Anglo-Irish Literature". www.ricorso.net. Archived from the original on 25 July 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ Yeats 1994, p. vii.

- ^ W. B. Yeats, Autobiographies (1956), p. 12. London: Macmillan.

- ^ Gordon Bowe, Nicola. "Two Early Twentieth-Century Irish Arts and Crafts Workshops in Context". Journal of Design History, Vol. 2, No. 2/3 (1989). 193–206

- ^ Shapley, Maggie (2013). "Poole, Ruth Lane (1885 - 1974)". The Australian Women's Register.

- ^ Foster 1997, p. xxviii.

- ^ Foster 1997, p. xxvii.

- ^ Foster 1997, p. 24.

- ^ Hone 1943, p. 28.

- ^ Foster 1997, p. 25.

- ^ Sessa, Anne Dzamba; Richard Wagner and the English; p. 130. ISBN 978-0-8386-2055-7

- ^ "APA PsycNet". psycnet.apa.org. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ a b c Yeats in Bedford Park Archived 30 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine, chiswickw4.com

- ^ Jordan 2003, p. 119.

- ^ Hone 1943, p. 33.

- ^ "The attraction of Bedford Park" Archived 19 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine by Amy Davies, 8 April 2013, Weidenfeld & Nicolson

- ^ Foster 1997, p. 37.

- ^ Paulin, Tom. Taylor & Francis, 2004. "The Poems of William Blake" Archived 15 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 3 June 2007.

- ^ Doody 2018, pp. 10–12.

- ^ Doody 2018, pp. 116–123.

- ^ Doody 2018, pp. 207, 280.

- ^ Hone 1943, p. 83.

- ^ Papp, James R. "Review [The Rhymers' Club: Poets of the Tragic Generation by Norman Alford]". Nineteenth-Century Literature, Vol. 50, No. 4, March 1996, pp. 535–538 JSTOR 2933931

- ^ Lancashire, Ian. "William Blake (1757–1827)" Archived 14 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Department of English, University of Toronto, 2005. Retrieved on 3 June 2007.

- ^ "William Blake: The Four Zoas". Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ^ Burke, Martin J. "Daidra from Philadelphia: Thomas Holley, Chivers and The Sons of Usna Archived 26 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine". Columbia University, 7 October 2005. Retrieved on 15 July 2007.

- ^ Ellmann 1948, p. 97.

- ^ Mendelson, Edward (ed.) "W. H. Auden" Archived 10 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine. The Complete Works of W.H. Auden: Prose, Vol. II, 1939–1948, 2002. Retrieved on 26 May 2007.

- ^ Foster 1997, pp. 82–85.

- ^ Alspach, Russell K. "The Use by Yeats and Other Irish Writers of the Folklore of Patrick Kennedy". The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 59, No. 234, December 1946, pp. 404–412

- ^ Gould, Warwick (2004). "Gyles, Margaret Alethea (1868–1949)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/59193. Retrieved 1 August 2015. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Nally, Claire V. "National Identity Formation in W. B. Yeats' A Vision". Irish Studies Review, Vol. 14, No. 1, February 2006, pp. 57–67

- ^ Foster 1997, p. 103.

- ^ Cullingford, Elizabeth. "How Jacques Molay Got Up the Tower: Yeats and the Irish Civil War". English Literary History, Vol. 50, No. 4, 1983, pp. 763–789

- ^ Foster 1997, p. 57.

- ^ Uddin Khan, Jalal. "Yeats and Maud Gonne: (Auto)biographical and Artistic Intersection". Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics, 2002.

- ^ Foster 1997, pp. 86–87.

- ^ "William Butler Yeats". BBC Four."William Butler Yeats 1865–1939". Archived from the original on 5 February 2008. Retrieved 20 June 2007.

- ^ a b c d Cahill, Christopher (December 2003). "Second Puberty: The Later Years of W. B. Yeats Brought His Best Poetry, along with personal melodrama on an epic scale". theatlantic.com. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ a b Ó Corráin, Donnchadh (2 July 2007). "William Butler Yeats". University College Cork. Archived from the original on 2 July 2007. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- ^ Jordan 2003, pp. 139–153; Jordan 1997, pp. 83–88

- ^ Jordan 2000, pp. 13–141.

- ^ "Woburn Walk ~ London's first pedestrian shopping street & the home of W.B. Yeats". londonunveiled.com. 4 July 2013. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- ^ Foster 1997, p. 394.

- ^ Malins & Purkis 1994, p. 124.

- ^ Corcoran, Neil. After Yeats and Joyce: Reading Modern Irish Literature. Oxford University Press, 1997, p. viii

- ^ Foster 2003, pp. 486, 662.

- ^ Foster 1997, p. 183.

- ^ Text reproduced from Yeats's own handwritten draft.

- ^ Foster 1997, p. 184.

- ^ a b Sophocles; Yeats, William Butler (1989). W.B. Yeats, the Writing of Sophocles' King Oedipus: Manuscripts of W.B. Yeats. American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0-87169-175-0. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ a b c Torrance, Isabelle; O'Rourke, Donncha (6 August 2020). Classics and Irish Politics, 1916–2016. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-886448-6. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ "Irish Genius: The Yeats Family and The Cuala Press" Archived 14 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Trinity College Dublin, 12 February 2004. Retrieved on 2 June 2007.

- ^ Monroe, Harriet (1913). "Poetry". (Chicago) Modern Poetry Association. 123

- ^ Sands, Maren. "The Influence of Japanese Noh Theater on Yeats Archived 1 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine". Colorado State University. Retrieved on 15 July 2007.

- ^ Foster 2003, pp. 59–66.

- ^ Lady Gregory, Augusta (1904), Gods and Fighting Men: The Story of the Tuatha de Danann and of the Fianna of Ireland, p. xiv

- ^ Sanford, John (18 April 2001). "Roy Foster: Yeats emerged as poet of Irish Revolution, despite past political beliefs". Stanford University. Archived from the original on 8 May 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ Ellmann 1948, p. 244.

- ^ Sternlicht, Sanford V. A Reader's Guide to Modern Irish Drama, Syracuse University Press, 1998, p. 48

- ^ Nally, Claire. 2010. Envisioning Ireland: W. B. Yeats's Occult Nationalism. Peter Lang

- ^ Allison, Jonathan (ed.). 1996. Yeats's Political Identities: Selected Essays. University of Michigan Press

- ^ Jordan 2003, p. 107.

- ^ Mann, Neil. "An Overview of A Vision" Archived 7 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine. The System of W. B. Yeats's A Vision. Retrieved on 15 July 2007.

- ^ Gonne MacBride, Maud. A Servant of the Queen. Gollanz, 1938 pp. 287–289

- ^ Brown, Terence. The Life of W. B. Yeats: A Critical Biography. Wiley-Blackwell, 2001, p. 347. ISBN 978-0-631-22851-6

- ^ Foster 2003, pp. 105, 383.

- ^ Mann, Neil. "Letter 27 July 1924" Archived 28 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine. The System of W. B. Yeats's A Vision. Retrieved on 24 April 2008.

- ^ "Nobel Prize in Literature 1923". NobelPrize.org. Archived from the original on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- ^ Foster 2003, p. 245.

- ^ a b Moses, Michael Valdez. "The Poet As Politician Archived 6 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine". Reason, February 2001. Retrieved on 3 June 2007.

- ^ Foster 2003, pp. 246–247.

- ^ Foster 2003, pp. 228–239.

- ^ "William Butler Yeats". Oireachtas Members Database. Archived from the original on 8 November 2018. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ Foster 2003, p. 293.

- ^ a b c Foster 2003, p. 294.

- ^ Foster 2003, p. 296.

- ^ "Seanad Resumes: Debate on Divorce Legislation Resumed". Seanad Éireann, Vol. 5. 11 June 1925. Archived from the original on 10 June 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2007.

- ^ a b Foster 2003, p. 333.

- ^ Mulhall, Ed."Yeats as ‘Smiling Public Man’: the Nobel Poet and the new State". RTE, 2023. Retrieved 6 December 2023

- ^ Foster 2003, p. 468.

- ^ Wyndham, Diana; Kirby, Michael (2012), Norman Haire and the Study of Sex, Sydney University Press, Foreword, and pp. 249–263, ISBN 978-1-74332-006-8

- ^ "The Life and Works of William Butler Yeats" Archived 12 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine. National Library of Ireland (search for Steinach). Retrieved on 19 October 2008.

- ^ Foster 2003, pp. 504, 510–511.

- ^ Letter to Dorothy Wellesley, 17 June 1935; cited Ellmann, "Yeats's Second Puberty", The New York Review of Books, 9 May 1985

- ^ "William Butler Yeats papers". library.udel.edu. University of Delaware. Archived from the original on 2 November 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ^ Marlowe, Lara (28 January 2014). "The end of Yeats: work and women in his last days in France". The Irish Times.

- ^ Jordan 2003, p. 114.

- ^ Foster 2003, p. 651.

- ^ Foster 2003, p. 656.

- ^ Jordan 2003, p. 115.

- ^ Allen, James Lovic. "'Imitate Him If You Dare': Relationships between the Epitaphs of Swift and Yeats". An Irish Quarterly Review, Vol. 70, No. 278/279, 1981, p. 177

- ^ "The Documents". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- ^ Ulanov, Barry. Makers of the Modern Theater. McGraw-Hill, 1961

- ^ Gale Research International. Twentieth Century Literary Criticism, No. 116. Gale Cengage Learning, 2002, p. 303

- ^ Finneran, Richard. Yeats: An Annual of Critical and Textual Studies 1995. University of Michigan Press, 1997. 82

- ^ Logenbach, James. Stone Cottage: Pound, Yeats, and Modernism. Oxford University Press, 1988, pp. 13–14

- ^ Bell, Vereen. Yeats and the logic of formalism. University of Missouri Press, 2006. 132

- ^ Seiden 1962, p. 179.

- ^ O'Neill (2003), p. 6.

- ^ Martin, Wallace. Review of "Tragic Knowledge: Yeats' "Autobiography" and Hermeneutics" by Daniel T. O'Hara. Contemporary Literature. Vol. 23, No. 2, Spring 1982, pp. 239–243

- ^ Paul, S. K. (1 January 2006). The Complete Poems of Rabindranath Tagore's Gitanjali: Texts and Critical Evaluation. Sarup & Sons. p. 29. ISBN 978-81-7625-660-5.

- ^ Howes, Marjorie. Yeats's nations: gender, class, and Irishness. Cambridge University Press, 1998, pp. 28–31

- ^ Seiden 1962, p. 153.

- ^ Bloom, Harold. Yeats. Oxford University Press, 1972, p. 168 ISBN 978-0-19-501603-1

- ^ Raine, Kathleen. Yeats the Initiate. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1990, pp. 327–329. ISBN 978-0-389-20951-5

- ^ Holdeman, David. The Cambridge Introduction to W. B. Yeats. Cambridge University Press, 2006 ISBN 978-0-521-54737-6, p. 80

- ^ Spanos, William. ″Sacramental Imagery in the Middle and Late Poetry of W. B. Yeats.″ Texas Studies in Literature and Language. (1962) Vol. 4, No. 2. pp. 214–228.

- ^ Lorenz, Dagmar C. G. Transforming the Center, Eroding the Margins. University of Rochester Press, 2004, p. 282. ISBN 978-1-58046-175-7

- ^ Powell, Grosvenor E. "Yeats's Second Vision: Berkeley, Coleridge, and the Correspondence with Sturge Moore". The Modern Language Review, Vol. 76, No. 2, April 1981, p. 273

- ^ "Sligo: W.B. Yeats Statue". atriptoireland.com. 8 July 2014. Archived from the original on 3 May 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ Standing Figure: Knife Edge, LH 482 cast 0 Archived 15 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Henry Moore Foundation

- ^ Bromwell, Philip (8 July 2020). "'Hidden gem' restored in Dublin's St Stephen's Green". RTÉ News. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ Eddins, Stephen (2011). "Kind". AllMusic Review. Archived from the original on 7 January 2021. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ Cohen, Aaron I. (1987). International Encyclopedia of Women Composers. Books & Music (USA). ISBN 978-0-9617485-0-0.

- ^ "Rocky path to the lighthouse". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ "Yeats, William Butler". English Heritage. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

Works cited

edit- Doody, Noreen (2018). The Influence of Oscar Wilde on W. B. Yeats: "An Echo of Someone Else's Music". Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3-319-89547-5.

- Ellmann, Richard (1948). Yeats: The Man and the Masks. New York: Macmillan.

- Foster, R. F. (1997). W. B. Yeats: A Life. Vol. I: The Apprentice Mage. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-288085-7.

- Foster, R. F. (2003). W. B. Yeats: A Life. Vol. II: The Arch-Poet 1915–1939. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-818465-2.

- Hone, Joseph (1943). W. B. Yeats, 1865–1939. New York: Macmillan Publishers. OCLC 35607726.

- Jordan, Anthony J. (1997). Willie Yeats & The Gonne-MacBrides. Westport Books. ISBN 978-0-9524447-1-8.

- Jordan, Anthony J. (2000). The Yeats Gonne MacBride Triangle. Westport Books. ISBN 978-0-9524447-4-9.

- Jordan, Anthony J. (2003). W. B. Yeats: Vain, Glorious, Lout – A Maker of Modern Ireland. Westport Books. ISBN 978-0-9524447-2-5.

- Malins, Edward; Purkis, John (1994). A Preface to Yeats (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-582-09093-4.

- O'Grady, David (Autumn 2016). "Yeats and Zen and a Horseman Passing By: A Buddhist Source for Yeats's Epitaph". New Hibernia Review / Iris Éireannach Nua. 20 (3): 125–140. doi:10.1353/nhr.2016.0045. JSTOR 44807219.

- O'Neill, Michael (2003). Routledge Literary Sourcebook on the Poems of W. B. Yeats. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-23475-7.

- Seiden, Morton (1962). William Butler Yeats. Michigan State University Press.

- Yeats, W. B. (1994). The Collected Poems of W. B. Yeats. Wordsworth Poetry Library. ISBN 978-1-85326-454-2.

Further reading

edit- Jeffares, A. Norman (1988). W. B. Yeats. A New Biography. Hutchinson. ISBN 978-0-09173-938-6.

- Jeffares, A. Norman; MacBride White, Anna (1992). The Gonne-Yeats Letters 1893-1938. Always Your Friend. Hutchinson. ISBN 978-0-09174-000-9.

External links

edit| External videos | |

|---|---|

| Presentation by R. F. Foster on W. B. Yeats: A Life: The Apprentice Mage, 7 December 1997, C-SPAN |

- The National Library of Ireland's exhibition, Yeats: The Life and Works of William Butler Yeats Archived 3 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Works by W. B. Yeats at Project Gutenberg

- Works by W. B. Yeats at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Yeats's correspondence and other archival records Archived 5 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Special Collections Research Center

- Collection of Yeats family papers at John J. Burns Library, Boston College

- Yeats and Mysticism, BBC Radio 4 discussion with Roy Foster, Warwick Gould and Brenda Maddox (In Our Time, 31 January 2002)

- Yeats and Irish Politics, BBC Radio 4 discussion with Roy Foster, Fran Brearton & Warwick Gould (In Our Time, 17 April 2008)

- W.B. Yeats Collection, 1875–1965 and Maud Gonne and W.B. Yeats Papers at Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University

- W.B. Yeats at the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin.

- Yeats family letters at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library

- William Butler Yeats on Nobelprize.org