Viva Villa! is a 1934 American pre-Code film directed by Jack Conway and starring Wallace Beery as Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa. The screenplay was written by Ben Hecht, adapted from the 1933 book Viva Villa! by Edgecumb Pinchon and O. B. Stade. The film was shot on location in Mexico and produced by David O. Selznick. There was uncredited assistance with the script by Howard Hawks, James Kevin McGuinness, and Howard Emmett Rogers. Hawks and William A. Wellman were also uncredited directors on the film.[citation needed]

| Viva Villa! | |

|---|---|

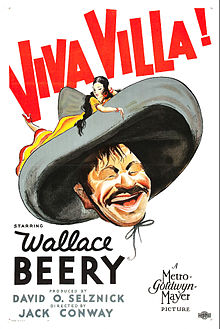

Film poster | |

| Directed by | Jack Conway Uncredited: Howard Hawks William Wellman |

| Written by | Ben Hecht Uncredited: Howard Hawks James Kevin McGuinness Howard Emmett Rogers |

| Based on | Viva Villa! (book) by Edgecumb Pinchon O. B. Stade |

| Produced by | David O. Selznick |

| Starring | Wallace Beery Fay Wray Leo Carrillo |

| Cinematography | Charles G. Clarke James Wong Howe |

| Edited by | Robert J. Kern |

| Music by | Herbert Stothart |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date |

|

Running time | 115 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1,022,000[1][2] |

| Box office | $1,969,000 (worldwide rentals)[1][2] |

The film is a fictionalized biography of Pancho Villa starring Beery in the title role and featuring Fay Wray, who had played the leading lady in King Kong the previous year. The supporting cast includes Leo Carillo, Donald Cook, Stuart Erwin, Henry B. Walthall, Joseph Schildkraut and Katherine DeMille.

Plot edit

After seeing his poor father lose his land and be whipped to death for protesting, young Pancho Villa stabs one of the killers, then heads off into the hills of Chihuahua, Mexico during the 1880s. As a grown man, Villa and a band of rebel bandits, including his trusted ally Sierra, kill wealthy landowners and become heroes to their fellow "peons".

A wealthy aristocrat, Don Felipe, arranges an introduction for Villa to the distinguished and eloquent Francisco Madero, who resents what has become of Mexico under the rule of president Porfirio Díaz and persuades Villa to help him fight for liberty, not just for personal gain. The coarse and illiterate Villa is humbled in the presence of Madero and agrees to fight for his cause. He also is attracted to Don Felipe's beautiful sister Teresa, although there are many women in Villa's life, including one he is married to, Rosita.

Villa's exploits are made even more colorful by an American newspaper reporter, Johnny Sykes, to whom Villa has taken a great liking. While drunk, Sykes is misinformed and reports that Villa has already overtaken the village of Santa Rosalia in a great victory for his men. Disobeying the orders of Madero and the arrogant General Pascal, simply to help his newspaper friend, Villa stages a raid on Santa Rosalia, as well as on Juarez.

Madero ultimately assumes office in Mexico City, then commands Villa to disband his personal army. Villa agrees, but when Sierra kills a bank teller just so Villa can withdraw his money, Villa himself ends up sentenced to death. A gloating General Pascal mocks the way Villa pleads for his life, then reads a telegram from Madero, ordering that Villa instead be exiled from the country.

Alone and drunk in El Paso, Texas, feeling forsaken by his homeland, Villa is visited by Sykes, who informs him that Madero has been assassinated by the power-mad Pascal and his men. Villa returns to Mexico and rebuilds his own army, recruiting tens of thousands to ride by his side. Together they storm the capital, where Pascal is subjected to a particularly gruesome death. Villa takes what he wants, but when Teresa resists and he physically assaults her, she draws a gun that her brother Don Felipe has given her for protection. Sierra intervenes and murders her.

Villa appoints himself president but is ineffectual, unable to restore Madero's dream of land reform for Mexico's poor. He ultimately agrees to step aside and go back to where he belongs, including to his wife. Before he can, with Sykes by his side, Villa is gunned down by Don Felipe out of revenge for his sister. Sykes vows to keep Villa's memory alive, telling his dying friend that he is no longer news, but history.

Cast edit

- Wallace Beery as Pancho Villa

- Leo Carrillo as Sierra

- Fay Wray as Teresa

- Donald Cook as Don Felipe de Castillo

- Stuart Erwin as Jonny Sykes

- Henry B. Walthall as Francisco Madero

- Joseph Schildkraut as Gen. Pascal

- Katherine DeMille as Rosita Morales (as Katherine de Mille)

- George E. Stone as Emilio Chavito

- Phillip Cooper as Pancho Villa as a boy

- David Durand as Bugle boy

- Frank Puglia as Pancho Villa's father

- Ralph Bushman as Wallace Calloway, reporter (as Francis X. Bushman Jr.)

- Adrian Rosley as Alphonso Mendoza

- Henry Armetta as Alfredo Mendosa

Production and release edit

David O. Selznick began filming Viva Villa! in 1932 in Mexico. Between filming and its release in April 1934, the film went through a development hell.[3]

Initially, Lee Tracy was cast to play a role of Jonny Sykes. However, following an incident on a Mexican balcony, from which he urinated on military cadets during a parade, he was fired from the film and eventually was replaced by Stuart Erwin.[4]

On September 29, 1933, Pancho Villa's son, Pancho Augustin Villa Jr. was signed to cast in a role of a young Pancho Villa.[5]

The film also experienced script problems requiring a change of as many as three writers and two directors (William Wellman and Howard Hawks, both uncredited).

Viva Villa! premiered at the Paramount Theatre in Los Angeles on May 17, 1934.[6]

When the film premiered in Mexico on September 7, 1934, exploding firecrackers interrupted the showing.[7]

Reception edit

Viva Villa! was popular at the box office[8] and was voted one of the ten best pictures of 1934 by The Film Daily's annual poll of critics.[9]

Variety called the film a "corking western",[10] while Helen Brown-Norden of Vanity Fair wrote "There is also no denying the fact that Wallace Beery is not everybody's Villa".[3]

During the film's production, the Mexican press called it "derogatory to Mexico", and urged the film to be boycotted in Mexico.[11]

Box office edit

In its initial release Viva Villa! earned total theater rentals of $1,875,000, with $941,000 from the US and Canada and $934,000 elsewhere. A 1949 re-release earned an additional $94,000 in foreign rentals, resulting in an overall profit of $157,000.[1][2]

Awards edit

The picture was nominated for the following Academy Awards:[12]

In popular culture edit

Viva Villa! partially inspired the creation of Elia Kazan's 1952 film Viva Zapata!, written by John Steinbeck and starring Marlon Brando and Anthony Quinn.

See also edit

- Let's Go with Pancho Villa - a 1936 Mexican film about Villa

- And Starring Pancho Villa as Himself, starring Antonio Banderas

References edit

- ^ a b c Glancy, H. Mark (1992). "MGM film grosses, 1924-1948: The Eddie Mannix Ledger". Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. 12 (2): 127–144. doi:10.1080/01439689200260081.

- ^ a b c Glancy, H. Mark (1992). "Appendix". Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. 12 (S2): 1–20. doi:10.1080/01439689208604539.

- ^ a b Norden, Helen Brown (June 1934). "Hollywood's Mexico". Vanity Fair.

- ^ Levin, Meyer (June 1, 1934). "The Candid Cameraman". Esquire.

- ^ Associated Press (September 29, 1933). "Villa's Son to Appear in Movie About Father". Evening Star. p. D-8. LCCN 83045462 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ "At the Movies". The Bismarck Tribune. May 17, 1934. LCCN 85042243 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ (September 7, 1934) Explosions Halt Film; Firecrackers Alarm Mexican Audience at "Viva Villa". The New York Times. p. 25.

- ^ Churchill, Douglas W. The Year in Hollywood: 1934 May Be Remembered as the Beginning of the Sweetness-and-Light Era; The New York Times [New York, N.Y.] p. X5.

- ^ Alicoate, Jack (1935). "The 1935 Film Daily Year Book of Motion Pictures, 17th Annual Edition". The Film Daily.

- ^ "Viva Villa!". Variety. December 31, 1933.

- ^ "Mexicans Urge Film Ban; Declare Showing of 'Viva Villa' Would Cost Nation Respect". The New York Times. 25 November 1933.

- ^ "The 7th Academy Awards (1935) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

Further reading edit

- Curtis Marez, "Pancho Villa Meets Sun Yat-Sen: Third World Revolution and the History of Hollywood Cinema," American Literary History 17.3 (2005): 486–505.