| Lightmoor Colliery | |

|---|---|

Lightmoor Colliery engine house | |

| General information | |

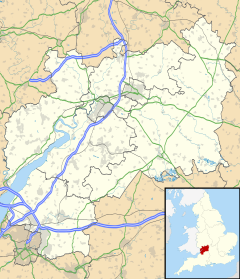

| Location | Gloucestershire, England, UK |

| Coordinates | 51°48′23″N 2°31′17″W / 51.806487°N 2.521456°W |

| Grid position | grid reference SO6168007887 |

Lightmoor Colliery, near Cinderford, in the Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire, was a major colliery.

Background

editAlthough coal mining, on a small scale, took place in the Forest of Dean since before Roman times,[1] it was not until the construction of three large, coke-fired, ironworks at Cinderford, Whitecliff and Parkend, in the last decade of the seventeenth century, that the exploitation of coal occourred to any great degree.[2] Initially, it proved impossible to produce coke from the local coal that was ideal for smelting[3] and, almost certainly, this was a major factor in the failure of all three furnaces within a decade of them opening.

Around 1820, Moses Teague, whilst borrowing the cupola furnace at Darkhill Ironworks, discovered a way to make good iron from local coke. To exploit his discovery he reopened Parkend Ironworks in 1824 and Cinderford Ironworks in 1829 (Whitecliff was never to reopen).[4][5]

History

editA report by , title 'At the begining of the nineteenth century, Lightmoor Colliery worked several gales, of which the first was awarded to Moses Teague and William Crawshay in 1841. Work had begun previously in about 1832, and there were two shafts by 1835. Pumping and winding engines were working by 1841 and there were four shafts by 1854. Further expansion included deepening of the shafts (to 936 ft) and acquisition of adjacent gales, and the colliery became one of the largest in Dean, producing 86,508 tons in 1856 and 800-900 tons/day in 1906. 594 persons were employed underground, with 110 on the surface, in 1899. The colliery worked the top of the Upper Coal Measures (Supra-Pennant Group), which includes the Twenty Inch, Lowery, Starkey, Rocky and Churchway High Delf Seams, mainly household coal. Lightmoor had an early tramroad connection with the Forest of Dean Tramroad at Ruspidge, replaced by a private line to the Forest of Dean Branch near Cinderford in 1854; there was also a connection with the Severn and Wye Railway's mineral loop. In later years there were problems with water, leading to the purchase of Speech House Hill and (jointly with Foxes Bridge) Trafalgar Collieries. Closure came on 8th June 1940, and for a time the buildings were used for military purposes.

History

editA survey of Forest of Dean collieries in 1841, by Thomas Sopwith,[6] stated that, between 1832 and 1838, Moses Teague had made and application in writing for permission to mine coal in an extension of the Meerbrook Level. The application was not granted, but together with William Crawshay (a South Wales iron master) he had 'erected works and proceeded as if it had been'. Crawshay had a three-quarters share in the mine, and a three-twentieth share in Cinderford Ironworks; for which the mine and other coal concerns around Cinderford, were aquired to provide a supply of coal.[7]

The expansion of the Meerbrook Level, on the site of Lightmoor Colliery, is believed to have begun in 1832 and a plan by Sopwith, dated 1835, shows two shafts in existance; one which was to become the pumping shaft and the other a winding shaft, and then later the smoke pit. Sopwith's survey also revealed that, by 1841, there were pumping and winding engines, each with their own engine house. The pits had been sunk down 220 yards but they still had another 20 yards to go and the coal output was nil. Possibly a small amount of coal was being won and used in the engine boilers. According to an article on developments at the colliery, published in the Dean Forest Mercury in 1899, coal was first struck in 1846.[8]

In 1854 William Crawshay conveyed his interests in the concerns to his son Henry who it seems had been managing his fathers interests in the Forest for some time. With regards to the colliery itself four shafts had now been sunk, the original pumping shaft; now 875 feet deep, two winding shafts; North and South, and an upcast shaft. The original winding shaft was now used to remove the foul air from the underground workings and for the smoke and exhaust steam from the underground boilers and engines; these three were all 894 feet deep. In 1858 the pumping shaft was described as being 9 ft. 6 in. by 14 ft. The pumping engine was supplied by the Neath Abbey Iron Co. in 1845 and was of the Cornish Beam condensing type. It had a 78 inch diameter cylinder with a nine feet stroke, eight feet in the shaft. It was connected to an 18 inch diameter forcing pump with a 90 yard lift, a 9 inch forcing pump of 80 yards lift and a 9 inch bucket pump with a lift of 130 yards. With the engine working at seven strokes per minute 605 gallons of water could be lifted in that time. The water was delivered into the old Meerbrook Level which carried it away into the Cinderford Brook. During the drier summer weather the engine worked at three and a half strokes per minute. At seven stokes the four egg-ended boilers, each 40 feet long and 6 ft. 6 in. in diameter, used to supply the steam consumed 12 tons of coal in twenty-four hours. At around this period the output of the colliery was 86, 508 tons per year. In 1861 William Crawshay, writing to his brother Richard, described Henryís works thus; ëhis Pits, Engines and Collieries are the most perfect in the Kingdom.í About 1862 Henry Crawshay, with financial assistance from his father, bought out the interests of his partners in the Forest for £50,000. The colliery was extended over the years with other gales being acquired. By 1863 the Resolution and Safeguard gale had been bought and it was intended to sink new shafts on this property at Reform Bridge to the south-west of Lightmoor. to bring the coal from these shafts it was planned that the Lightmoor Railway, as Crawshayís private line was known, would be extended but although earthworks for the railway were prepared no other work was done. Another gale aquired was Soundwell. Henry Crawshay treated his men very well and their regard for him was shown during a coal strike for three months in the winter of 1874-5 when they continued to work. By this date it would appear that Henryís son Edwin was managing the concerns for Henry Crawshay & Son, Henry having taken both his sons William and Edwin into partnership. Upon the death of Henry, aged 67, on 17th November 1879 at his home of Oaklands Park near Newnham, [something strange happened check with Mabel] In February 1880 an accident occured which could have had serious consequences for the colliery. One of the most dreaded occurences underground is fire and one Saturday night it was found that the timbering in the main roadway was alight for a distance of 10 - 15 yards. By the time assistance arrived this had increased considerably especially as great difficult was encountered in obtaining water. Eventually it was got from the extreme dip of the workings and brought to the scene of the fire in a ëgooseí, an iron vessel drawn by horse. Relays of men worked through Sunday and until five oíclock Monday morning to extinguish the flames. As considerable damage had been done to the roof supports in the main roadway the colliery was unable to work for a further day. On the 14 August 1889 Henry Crawshay & Co. Ltd. was formed with an authorised capital of £140,000 in 4,000 preference and 3,000 ordinary £20 shares. The new company was to acquire both Henry Crawshay & Sons and Henry Crawshay & Co. The first directors were William Crawshay, Sir Gabriel Goldney, Tudor Crawshay, Colonel Augustus Arthur Kilner Brasier Creagh, and Frederick Hastings Goldney. On the 4th January 1894 another occurence brought the colliery to a stand. For some reason the ësheeveí, or pulley wheel, on the top of the south shaft headframe moved on its axle. This meant that winding was impossible and the men underground had to be hauled up the Big Shaft. The wheel defied every effort to move it back for almost a week during which time nearly 600 men and boys were out of work and 500 tons of coal a day were lost at a time of great demand.

In February 1899 the Dean Forest Mercury carried a long report of developments at Lightmoor. It would seem that the 1890s had been a period of change and expansion. A new set of screens had recently been installed, possibly by the firm of Heanan & Froude of Worcester, which replaced the old method of raking the coals on a bank. They were worked by a horizontal egine with a 12 inch cylinder and two foot stoke. Electrical plant had also been installed to provide light, both on the surface and underground. The provision of this was in the hands of Messrs. Scott and Mountain Ltd, of Newcastle-on-Tyne and a new engine house had been erected containing a vertical high-speed engine. It was intended that a second engine should be provided to act as standby. Working at 60 lbs. pressure with an 111/2 inch cylinder by 9 inch stoke and fitted with piston valves and Pickering governors the engine made 180 revolutions per minute and produced about 15 h.p. The engines 3 ft. 6 in. flywheel was connected via a cotton belt to a ëTyneí horse-shoe pattern dynamo which gave an output of 45 amperes at 210 volts. The dynamo was connected to a switchboard at which point the current was split into two circuits. One supplied the surface buildings and the other supplied the underground lights by means of two cables taken down the shaft in wooden conduits. In 1898 the colliery had broken the record for the output from a Forest of Dean colliery due to the fact that in the development of the works great foresight was shown with regard to the future and the pit was one of the best of the Forest housecoal collieries. In 1899 there were 594 persons employed underground and 110 on the surface. Those working below were in safe hands whilst vbeing wound up and down the shaft as the winding engine in addition to the normal break also had a steam brake fitted at which a second man always attended whilst men were riding. This attention to detail and safety appears to have permiated throughout the management and working of the pit. The Deep Pit was later sunk further, to a depth of 936 feet, until the Brazilly seam was reached. This deepening passed through a further eighteen seams, the more important being the Twenty Inch or Smith Coal,the Lowery, Starkey, Rockey and Churchway High Delf. The area of coal worked was about 1,000 acres. The screening plant too was modernised and by 1935 was capable of handling up to eight hundred tons per day. In later years the big fear at Lightmoor was water. It was this that made the Lightmoor management purchase the Speech House Hill Colliery in 1903 and then to purchase Trafalgar Colliery jointly with Foxes Bridge in 1919. The closure of both Crump Meadow and Foxes Bridge put a great strain on Lightmoor, which together with the slump in demand for coal during the 1930s almost brought about closure but the fatal day was delayed until June 1940. Notice was first given in January 1933 that the gales would be surrendered in March due to the additional cost of pumping the Crump Meadow and Foxes Bridge water. The surrounding district were worried by the news in the knowledge that between seven and eight hundred men would be made unemployed. However, in February the managing director, Arthur Morgan informed the local press that ëI have beenh successful in my effortsí and that the colliery would not close for at least another twelve months. The wages bill at this time for Lightmoor was £70,000 a year. One rather startling statistic for 1933 was that a Mr. Alfred Drew, who had started work at the pit aged 13 years, had walked 140,000 miles to and from work over a period of fifty years from his home at Viney Hill, about four miles as the crow flies. In all that time he had never lost a shift through illness. In May 1940 it was announced that the colliery was to close the reason being put down to the exhaustion of the coal and the drift of men from the colliery to the war-time factories. This time there would be no redundancies as the 172 men could be absorbed at Crawshayís other collieries, Eastern United and Northern United. The output at this time being about 118 tons a day. Although the official date of closure was Saturday the 8th June 1940 some small coal was still being forwarded for a further three weeks although the last wagon of coal to go over the Lightmoor Railway was dispatched on the 5th June. At the time of closure the colliery was served by one Severn & Wye train per week, the 9.30 am Lydney - Coleford freight which traversed the Mineral Loop on Fridays only.

When the decision to close was made the question arose in respect of the recovery of the redundant track and colliery equipment. Lewis Brothers Ltd. of Eastmoors, Cardiff were commissioned by Sir Alexander Gibb & Partners, who were the agents and consulting engineers to the Ministry of Supply, to purchase on their behalf 6,000 tons of rails required in connection with the urgent construction of munitions factories. Lewis Bros. purchased the sidings in and around the colliery on 4th June 1940. They also consulted with the GWR to enquire if they would be willing to let them have the connecting branch from Bilson Junction on behalf of the Government, offering to remove the rails themselves. It seems to have been forgotten that the line was privately owned and belonged to the colliery. The sidings and the Lightmoor Railway were removed in July 1940.

References

edit- ^ title?

- ^ www.lightmoor.co.uk

- ^ Historical Metallurgy Society website

- ^ British History Online

- ^ Ralph Anstis, Man of Iron-Man of Steel, page 58

- ^ The Award of the Dean Forest Mining Commissioners as to the Coal and Iron Mines in Her Majesty's Forest of Dean, Thomas Sopwith, 1841

- ^ Forest of Dean Local History Society

- ^ Forest of Dean Local History Society