| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | Bicalutamide: • /baɪkəˈluːtəmaɪd/[1] • bye-kə-LOO-tə-myde[1] Casodex: • /ˈkeɪsoʊdɛks/[2] • KAY-soh-deks[2] |

| Trade names | Casodex, others |

| Other names | ICI-176,334; ZD-176,334 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a697047 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth[3] |

| Drug class | Nonsteroidal antiandrogen |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Well-absorbed; absolute bioavailability unknown[4] |

| Protein binding | Racemate: 96.1%[3] (R)-Isomer: 99.6%[3] (Mainly to albumin)[3] |

| Metabolism | Liver (extensively):[5][9] • Hydroxylation (CYP3A4) • Glucuronidation (UGT1A9) |

| Metabolites | • Bicalutamide glucuronide • Hydroxybicalutamide • Hydroxybicalutamide gluc. (All inactive)[5][3][6][7] |

| Onset of action | Unknown[8] |

| Duration of action | Unknown[8] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| Chemical and physical data | |

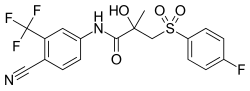

| Formula | C18H14F4N2O4S |

| Molar mass | 430.37 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture (of (R)- and (S)-enantiomers) |

| Melting point | 191 to 193 °C (376 to 379 °F) (experimental) |

| Boiling point | 650 °C (1,202 °F) (predicted) |

| Solubility in water | 0.005 |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Bicalutamide, sold under the brand name Casodex among others, is an antiandrogen medication that is primarily used to treat prostate cancer.[10] It is typically used together with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogue or surgical removal of the testicles to treat advanced prostate cancer.[12][10][13] Bicalutamide may also be used to treat excessive hair growth in women,[14] as a component of feminizing hormone therapy for transgender women,[15] to treat early puberty in boys,[16] and to prevent overly long-lasting erections in men.[17] It is taken by mouth.[10]

Common side effects in men include breast enlargement, breast tenderness, and hot flashes.[10] Other side effects in men include feminization and sexual dysfunction.[18] While the medication appears to produce few side effects in women, its use in women is not recommended by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).[19][10] Use during pregnancy may harm the baby.[10] Bicalutamide causes elevated liver enzymes in around 1% of people.[20][21] Rarely, it has been associated with cases of liver damage,[10] lung toxicity,[4] and sensitivity to light.[22][23] Although the risk of adverse liver changes is small, monitoring of liver function is recommended during treatment.[10]

Bicalutamide is a member of the nonsteroidal antiandrogen (NSAA) group of medications.[4] It works by blocking the androgen receptor (AR), the biological target of the androgen sex hormones testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT).[24] It does not lower androgen levels.[4] The medication can have some estrogen-like effects in men.[25][26][27] Bicalutamide is well-absorbed, and its absorption is not affected by food.[3] The elimination half-life of the medication is around one week.[3][10] It is believed to cross the blood–brain barrier and affect both the body and brain.[3]

Bicalutamide was patented in 1982 and approved for medical use in 1995.[28] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[29] Bicalutamide is available as a generic medication.[30] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$7 to US$144 per month.[31] In the United States it costs about US$10 and above per month.[32] The medication is sold in more than 80 countries, including most developed countries.[33][34][35] It is the most widely used antiandrogen in the treatment of prostate cancer, and has been prescribed to millions of men with the disease.[36][37][38][39]

References edit

- ^ a b Finkel, Richard; Clark, Michelle Alexia; Cubeddu, Luigi X. (2009). Pharmacology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 481–. ISBN 978-0-7817-7155-9. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ a b Sifton DW, PDR Staff (2002). PDR Drug Guide for Mental Health Professionals. Thomson/PDR. ISBN 978-1-56363-457-4. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cockshott ID (2004). "Bicalutamide: clinical pharmacokinetics and metabolism". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 43 (13): 855–878. doi:10.2165/00003088-200443130-00003. PMID 15509184.

These data indicate that direct glucuronidation is the main metabolic pathway for the rapidly cleared (S)-bicalutamide, whereas hydroxylation followed by glucuronidation is a major metabolic pathway for the slowly cleared (R)-bicalutamide.

- ^ a b c d Dart, Richard C. (2004). Medical Toxicology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 497, 521. ISBN 978-0-7817-2845-4. Archived from the original on 11 May 2016.

- ^ a b Lemke, Thomas L.; Williams, David A. (2008). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 121, 1288, 1290. ISBN 978-0-7817-6879-5. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ Dole EJ, Holdsworth MT (1997). "Nilutamide: an antiandrogen for the treatment of prostate cancer". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 31 (1): 65–75. doi:10.1177/106002809703100112. PMID 8997470.

page 67: Currently, information is not available regarding the activity of the major urinary metabolites of bicalutamide, bicalutamide glucuronide, and hydroxybicalutamide glucuronide.

- ^ Schellhammer PF (September 2002). "An evaluation of bicalutamide in the treatment of prostate cancer". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 3 (9): 1313–28. doi:10.1517/14656566.3.9.1313. PMID 12186624.

The clearance of bicalutamide occurs pre- dominantly by hepatic metabolism and glucuronidation, with excretion of the resulting inactive metabolites in the urine and faces.

- ^ a b Skidmore-Roth, Linda (16 July 2015). Mosby's Drug Guide for Nursing Students, with 2016 Update. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 117–. ISBN 978-0-323-17297-4. Archived from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ Grosse L, Campeau AS, Caron S, Morin FA, Meunier K, Trottier J, Caron P, Verreault M, Barbier O (August 2013). "Enantiomer selective glucuronidation of the non-steroidal pure anti-androgen bicalutamide by human liver and kidney: role of the human UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT)1A9 enzyme". Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 113 (2): 92–102. doi:10.1111/bcpt.12071. PMC 3815647. PMID 23527766.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Bicalutamide". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 29 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ Wass, John A.H.; Stewart, Paul M. (28 July 2011). Oxford Textbook of Endocrinology and Diabetes. OUP Oxford. pp. 1625–. ISBN 978-0-19-923529-2. Archived from the original on 11 May 2016.

- ^ Shergill, Iqbal; Arya, Manit; Grange, Philippe R.; Mundy, A. R. (2010). Medical Therapy in Urology. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 40. ISBN 9781848827042. Archived from the original on 28 October 2014.

- ^ Williams, Hywel; Bigby, Michael; Diepgen, Thomas; Herxheimer, Andrew; Naldi, Luigi; Rzany, Berthold (22 January 2009). Evidence-Based Dermatology. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 529–. ISBN 978-1-4443-0017-8. Archived from the original on 2 May 2016.

- ^ Randolph JF (December 2018). "Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy for Transgender Females". Clin Obstet Gynecol. 61 (4): 705–721. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000396. PMID 30256230.

- ^ Jameson, J. Larry; De Groot, Leslie J. (25 February 2015). Edndocrinology: Adult and Pediatric. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 2425–2426, 2139. ISBN 978-0-323-32195-2. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ Yuan J, Desouza R, Westney OL, Wang R (2008). "Insights of priapism mechanism and rationale treatment for recurrent priapism". Asian Journal of Andrology. 10 (1): 88–101. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7262.2008.00314.x. PMID 18087648.

- ^ Elliott S, Latini DM, Walker LM, Wassersug R, Robinson JW (2010). "Androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: recommendations to improve patient and partner quality of life". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 7 (9): 2996–3010. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01902.x. PMID 20626600.

- ^ Shapiro, Jerry (12 November 2012). Hair Disorders: Current Concepts in Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management, An Issue of Dermatologic Clinics. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 187–. ISBN 978-1-4557-7169-1. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ "Casodex- bicalutamide tablet". DailyMed. 1 September 2019. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ Wellington K, Keam SJ (2006). "Bicalutamide 150mg: a review of its use in the treatment of locally advanced prostate cancer" (PDF). Drugs. 66 (6): 837–50. doi:10.2165/00003495-200666060-00007. PMID 16706554. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ Lee K, Oda Y, Sakaguchi M, Yamamoto A, Nishigori C (May 2016). "Drug-induced photosensitivity to bicalutamide – case report and review of the literature". Photodermatology, Photoimmunology & Photomedicine. 32 (3): 161–4. doi:10.1111/phpp.12230. PMID 26663090.

- ^ Lee K, et al. (2016). "Drug-induced photosensitivity to bicalutamide – case report and review of the literature". Reactions Weekly. 1612 (1): 37. doi:10.1007/s40278-016-19790-1.

- ^ Singh SM, Gauthier S, Labrie F (February 2000). "Androgen receptor antagonists (antiandrogens): structure-activity relationships". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 7 (2): 211–47. doi:10.2174/0929867003375371. PMID 10637363.

- ^ Strauss III, Jerome F.; Barbieri, Robert L. (28 August 2013). Yen & Jaffe's Reproductive Endocrinology: Physiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Management. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 688–. ISBN 978-1-4557-5972-9. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

Bone density improves in men receiving bicalutamide, most likely secondary to the 146% increase in estradiol and the fact that estradiol is the major mediator of bone density in men.

- ^ Marcus, Robert; Feldman, David; Nelson, Dorothy; Rosen, Clifford J. (8 November 2007). Osteoporosis. Academic Press. pp. 1354–. ISBN 978-0-08-055347-4. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016.

- ^ Mahler C, Verhelst J, Denis L (May 1998). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of the antiandrogens and their efficacy in prostate cancer". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 34 (5): 405–17. doi:10.2165/00003088-199834050-00005. PMID 9592622.

- ^ Fischer, Janos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 515. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 381. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ^ "Bicalutamide". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ "NADAC as of 2016-12-07 | Data.Medicaid.gov". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- ^ "Bicalutamide – International Drug Names". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ Akaza H (1999). "[A new anti-androgen, bicalutamide (Casodex), for the treatment of prostate cancer—basic clinical aspects]". Gan to Kagaku Ryoho. Cancer & Chemotherapy (in Japanese). 26 (8): 1201–7. PMID 10431591.

- ^ "1999 Annual Report and Form 20-F" (PDF). AstraZeneca. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ Mukherji D, Pezaro CJ, De-Bono JS (February 2012). "MDV3100 for the treatment of prostate cancer". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 21 (2): 227–33. doi:10.1517/13543784.2012.651125. PMID 22229405.

- ^ Pchejetski, Dmitri; Alshaker, Heba; Stebbing, Justin (2014). "Castrate-resistant prostate cancer: the future of antiandrogens" (PDF). Trends in Urology & Men's Health. 5 (1): 7–10. doi:10.1002/tre.371. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 July 2018. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ Campbell, Todd (22 January 2014). "Slowing Sales for Johnson & Johnson's Zytiga May Be Good News for Medivation". The Motley Fool. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

[...] the most commonly prescribed treatment for metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer: bicalutamide. That was sold as AstraZeneca's billion-dollar-a-year drug Casodex before losing patent protection in 2008. AstraZeneca still generates a few hundred million dollars in sales from Casodex, [...]

- ^ Chang, Stephen (10 March 2010), Bicalutamide BPCA Drug Use Review in the Pediatric Population (PDF), U.S. Department of Health and Human Service, archived (PDF) from the original on 24 October 2016, retrieved 20 July 2016