- Sandbox for the article on Stanislavski's 'system'

Stanislavski's ‘system’ is a systematic approach to training actors that the Russian theatre practitioner Konstantin Stanislavski developed in the first half of the 20th century.[2] Thanks to its promotion and development by acting teachers who were former students and the many translations of Stanislavski's theoretical writings, the 'system' acquired an unprecedented ability to cross cultural boundaries and developed an international reach, dominating debates about acting in the West.[3] That many of its precepts seem to be common sense and self-evident testifies to its hegemonic success.[4] Actors frequently employ its basic concepts without knowing they do so.[5]

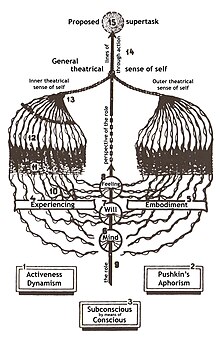

Stanislavski was the first practitioner in the West to propose that actor training should involve something more than merely physical and vocal training.[6] The 'system' cultivates what he calls the "art of experiencing" (to which he contrasts the "art of representation").[7] It mobilises the actor's conscious thought and will in order to activate other, less-controllable psychological processes—such as emotional experience and subconscious behaviour—sympathetically and indirectly.[8] In rehearsal, the actor searches for inner motives to justify action and the definition of what the character seeks to achieve at any given moment (a "task").[9]

Later, Stanislavski further elaborated the 'system' with a more physically grounded rehearsal process that came to be known as the "Method of Physical Action".[10] Minimising at-the-table discussions, he now encouraged an "active analysis", in which the sequence of dramatic situations are improvised.[11] "The best analysis of a play", Stanislavski argued, "is to take action in the given circumstances."[12]

Many actors routinely equate the 'system' with the American Method, although the latter's exclusively psychological techniques contrast sharply with the multivariant, holistic and psychophysical approach of the 'system,' which explores character and action both from the 'inside out' and the 'outside in' and treats the actor's mind and body as parts of a continuum.[13]

Stanislavski before his 'system' edit

Throughout his career, Stanislavski subjected his acting and direction to a rigorous process of artistic self-analysis and reflection.[14] His 'system' of acting developed out of his persistent efforts to remove the blocks that he encountered in his performances, beginning with a major crisis in 1906.[15]

Having worked as an amateur actor and director until the age of 33, in 1898 Stanislavski co-founded the Moscow Art Theatre (MAT) with Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko and began his professional career. The two of them were resolved to institute a revolution in the staging practices of the time. Benedetti offers a vivid portrait of the poor quality of mainstream theatrical practice in Russia before the MAT:

The script meant less than nothing. Sometimes the cast did not even bother to learn their lines. Leading actors would simply plant themselves downstage centre, by the prompter's box, wait to be fed the lines then deliver them straight at the audience in a ringing voice, giving a fine display of passion and "temperament." Everyone, in fact, spoke their lines out front. Direct communication with the other actors was minimal. Furniture was so arranged as to allow the actors to face front.[16]

Stanislavski's early productions were created without the use of his 'system'. His first international successes were staged using an external, director-centred technique that strove for an organic unity of all its elements—in each production he planned the interpretation of every role, blocking, and the mise en scène in detail in advance.[17] He also introduced into the production process a period of discussion and detailed analysis of the play by the cast.[18] Despite the success that this approach brought, particularly with his Naturalistic stagings of the plays of Anton Chekhov and Maxim Gorky, Stanislavski remained dissatisfied.[19]

Both his struggles with Chekhov's drama (out of which his notion of subtext emerged) and his experiments with Symbolism encouraged a greater attention to "inner action" and a more intensive investigation of the actor's process.[20] He began to develop the more actor-centred techniques of "psychological realism" and his focus shifted from his productions to rehearsal process and pedagogy.[21] He pioneered the use of theatre studios as a laboratory in which to innovate actor training and to experiment with new forms of theatre.[22] Stanislavski organised his techniques into a coherent, systematic methodology, which built on three major strands of influence: (1) the director-centred, unified aesthetic and disciplined, ensemble approach of the Meiningen company; (2) the actor-centred realism of the Maly; and (3) the Naturalistic staging of Antoine and the independent theatre movement.[23]

Stanislavski's earliest reference to his 'system' appears in 1909, the same year that he first incorporated it into his rehearsal process.[24] The Moscow Art Theatre adopted it as its official rehearsal method in 1911.[25]

Experiencing edit

A rediscovery of the 'system' must begin with the realization that it is the questions which are important, the logic of their sequence and the consequent logic of the answers. A ritualistic repetition of the exercises contained in the published books, a solemn analysis of a text into bits and tasks will not ensure artistic success, let alone creative vitality. It is the Why? and What for? that matter and the acknowledgement that with every new play and every new role the process begins again. (Jean Benedetti).[26]

The 'system' is based on "experiencing a role."[27] It demands that the actor "experience feelings analogous" to those that the character experiences "each and every time you do it."[28] Stanislavski approvingly quotes Salvini when he insists that an actor should really feel what he or she portrays, not merely in rehearsals when preparing the role but also "at every performance, be it the first or the thousandth."[29] On this basis, Stanislavski contrasts his own "art of experiencing" approach with what he calls the "art of representation" (in which experiencing forms one of the preparatory stages only) and "hack" acting (in which experiencing plays no part).[30] Stanislavski's approach seeks to stimulate the will to create afresh and to activate subconscious processes sympathetically and indirectly by means of conscious techniques.[31] In this way, it attempts to recreate in the actor the inner, psychological causes of behaviour, rather than to present a simulacrum of their effects.[32] Stanislavski recognised that in practice a performance is usually a mixture of the three trends (experiencing, representation, hack) but felt that experiencing should predominate.[33]

The range of training exercises and rehearsal practices that form the 'system' resulted from many years of sustained inquiry and experiment. Many may be discerned as early as 1905 in a letter of advice to Vera Kotlyarevskaya on how to approach the role of Charlotta in Chekhov's The Cherry Orchard:

First of all you must live the role without spoiling the words or making them commonplace. Shut yourself off and play whatever goes through your head. Imagine the following scene: Pishchik has proposed to Charlotta, now she is his bride... How will she behave? Or: Charlotta has been dismissed but finds other employment in a circus of a café-chantant. How does she do gymnastics or sing little songs? Do your hair in various ways and try to find in yourself things which remind you of Charlotta. You will be reduced to despair twenty times in your search but don't give up. Make this German woman you love so much speak Russian and observe how she pronounces words and what are the special characteristics of her speech. Remember to play Charlotta in a dramatic moment of her life. Try to make her weep sincerely over her life. Through such an image you will discover all the whole range of notes you need.[34]

The process of experiencing is used to create the inner, psychological aspect of a role, endowing it with the actor's individual feelings and own personality.[28] Stanislavski argues that this creation of an inner life should be the actor's first concern.[35] He groups together the training exercises intended to support the emergence of experiencing under the general term "psychotechnique".

Given circumstances and the Magic If edit

When I give a genuine answer to the if, then I do something, I am living my own personal life. At moments like that there is no character. Only me. All that remains of the character and the play are the situation, the life circumstances, all the rest is mine, my own concerns, as a role in all its creative moments depends on a living person, i.e., the actor, and not the dead abstraction of a person, i.e., the role (Stanislavski).[36]

Stanislavski's "Magic If" describes an ability to imagine oneself in a set of fictional circumstances and to envision the consequences of finding oneself facing that situation in terms of action.[37] The actor develops imaginary stimuli, which often consist of sensory details of the circumstances, in order to provoke an organic, subconscious response in performance.[38] These "inner objects of attention" form an "unbroken line" through a performance that create the inner life of the role.[39]

When experiencing the role, the actor is absorbed by the drama and immersed in its fictional circumstances; it is a state that the psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls "flow."[40] Stanislavski encouraged this absorption through the cultivation of "public solitude" and its "circles of attention," which he developed from the meditation techniques of yoga.[41] Stanislavski did not encourage complete identification with the role, however, since a genuine belief that one had become someone else would be pathological.[42]

Tasks and action edit

Action is the very basis of our art, and with it our creative work must begin (Stanislavski).[43]

Method of Physical Action edit

The roots of the Method of Physical Action stretch back to Stanislavski's earliest work as a director (in which he focused consistently on a play's action) and the techniques he explored with Meyerhold and later with the First Studio before the First World War (such as the experiments with improvisation and the practice of anatomising scripts in terms of bits and tasks).[44] He first explored the approach practically in his rehearsals for Three Sisters and Carmen in 1934 and Molière in 1935.[45]

Just as the First Studio, led by his assistant and close friend Leopold Sulerzhitsky, had provided the forum in which he developed his initial ideas for the 'system' during the 1910s, he hoped to secure his final legacy by opening another studio in 1935, in which the Method of Physical Action would be taught.[46] The Opera-Dramatic Studio embodied the most complete implementation of the training exercises described in his manuals.[47] Meanwhile, the transmission of his earlier work via the students of the First Studio was revolutionising acting in the West.[48] With the arrival of Socialist realism in the USSR, the MAT and Stanislavski's 'system' were enthroned as exemplary models.[49]

Analysis and criticism edit

From his earliest reference to his 'system' onwards, Stanislavski insisted that it was based on natural laws and that it was not, therefore, his invention.[50] Contemporary acting theory and theatre scholarship reject this claim as false.[51] Humanist assumptions underpinning his work: "human nature" as universal and transcendent of historical and socio-cultural differences - essentialist treatment of the human subject; that the proper function of art is to encourage a recognition of a common humanity by means of an expression of these universals.[52]

"The system may not be coherent as a theoretical system, even if the exercises work in practice."[53]

"However, thinking of the actors' voice and body as their instrument is a dichotomous way of thinking that brings about problems for Stanislavsky and his contemporaries."[54]

Insistence on the importance of experiencing limits the 'system' to Naturalism. Contains ideas/assumptions about personality and the self.[55]

Scrapboard edit

Need to check Benedetti 1999a citations

Dislike of the cinema for destroying the communication of actor and audience.[56]

Benedetti argues that "problems of character-creation are not, as had often been assumed, the central issue of the 'system.' The central issue is the structure and meaning of the play itself."[57]

As Jean Benedetti explains, Stanislavski "saw the voice as part of a total physical characterization in which the body responded organically to inner impulses."[58]

| “ | A further paradigmatic concept in Stanislavsky's training method is the idea that repetition and practice are needed. Stanislavski thought it was necessary for actors to establish habits, by means of repetition of exercises and approaches to work. His campaign, therefore, was to get performers to recognise the importance of daily work on the self and preparation for performance".[59] | ” |

Admiring the unique form of symbolism that he perceived in The Cherry Orchard in a letter to Chekhov, the director Vsevolod Meyerhold wrote that "the West is going to have to learn drama from you."[60]

"Meyerhold was the first to create Symbolist theatre in Russia".[61]

"In our days action in the theatre of direct conformity to life usually develops as a constant 'flow of life,' avoiding frequent subdivisions. Hence the long, undivided acts. In relativistic theatre the action is just as naturally broken up into separate episodes, fragments or 'numbers.' Moments where the action is stopped completely are possible. Abrupt accelerations or decelerations of the pace, as compared to life, are both considered possible and desirable. On occassion, totally unreal rhythms--even plain, anxious or ridiculing arhythmia--are used."[62]

"The universal recognition of Stanislavski's and Nemirovich-Danchenko's masterpieces of direction has been conditioned to a great degree by the organic connection between their work and the traditions of nineteenth-century Russian prose, which has enriched the cultural and spiritual heritage of mankind."[63]

In August 1908 he discussed a chapter on professional ethics for the actor from his draft Manual with the Marxist critic Anatoly Lunacharsky.[64]

| “ | Only the creative tasks should be conscious, the means of achieving them, unconscious. The unconscious though the conscious. This is the watchword which must guide our coming work.[65] | ” |

| “ | On the one theoretical hand, art communicates the artist's personal experience; in this sense, he travels toward Tolstoy, bringing to mind Romantic notions of sincere self-expression and the fusion of actor and character. On the other practical hand, acting generates its own experiential dimension in performance; here Stanislavsky accepts the alternation of actor and character. When he suggests evaluating performance on its own terms and seeing "truth" as relative to the play, he travels away from Tolstoy and anticipates developments in modernism that embrace the formal media of art: visual artists who create abstract art by drawing attention to paint and canvas, theatricalists who destroy realistic illusion unabashedly to show an actor on a stage, etc. Janus-like Stanislavsky looks backward to nineteenth-century traditions in art and forward to the twentieth.[66] | ” |

| “ | Now, it is necessary to rid oneself of the prejudice that it is possible to teach people 'to act' certain feelings. It can, I think, be stated quite definitely that no one can be taught to act.[67] | ” |

| “ | ‘The theatre and the cinema belong to different spheres and the things by which the theatre excites, attracts and charms us can never be provided by the cinema. It is really naïve to imagine that what currently has meaning in the theatre for audiences is outward form. That is not the life of the theatre. Theatre lives by the exchange of spiritual energy, which goes continuously back and forth between audience and actor; that contact of feeling that unites actor and audience with invisible threads. That will never and can never occur in the cinema where the living actor is absent, where the flow of spiritual motions is effected by mechanical means. In the theatre it is a living man who delights us, saddens us, disturbs us and calms us but in the cinema everyone and everything is only apparently real.[68] | ” |

Psychophysical technique edit

In 1911 he introduced classes in Émile Jaques-Dalcroze's eurhythmics and elements of yoga for the MAT company.[69]

In response to his characterisation work on Argan in Molière's The Imaginary Invalid in 1913, he concluded that "a character is sometimes formed psychologically, i.e. from the inner image of the role, but at other times it is discovered through purely external exploration."[70]

Relationship to Naturalism edit

In a journal note of 1908, Stanislavski wrote:

| “ | Explain the fact that every play needs the quintessence of life, not life itself. For instance: read some long-winded novel that doesn't appeal to you. You shut it at page ten. Cut the novel, leaving in what interests you and you respond. There's a great deal that is uninteresting in life. What interest is it to me how a man eats, drinks and washes, if he does not do it in a special way?[71] | ” |

See also Counsell's discussion.[72]

References edit

- ^ Whyman (2008, 38-42) and Carnicke (1998, 99).

- ^ Stanislavski began developing a 'grammar' of acting in 1906; his initial choice to call it his System struck him as too dogmatic, so he preferred to write it as his 'system' (without the capital letter and in inverted commas), in order to indicate the provisional nature of the results of his investigations. Modern scholarship follows that practice. See Benedetti (1999a, 169), Gauss (1999, 3-4), and Milling and Ley (2001, 1).

- ^ Carnicke (1998, 1, 167), Counsell (1996, 24), and Milling and Ley (2001, 1).

- ^ Counsell (1996, 25).

- ^ Counsell (1996, 25).

- ^ Gordon (2006, 38).

- ^ Benedetti (1999a, 201), Carnicke (2000, 17), and Stanislavski (1938, 16—36). Stanislavski's "art of representation" corresponds to Mikhail Shchepkin's "actor of reason" and his "art of experiencing" corresponds to Shchepkin's "actor of feeling"; see Benedetti (1999a, 202).

- ^ Benedetti (1999a, 170).

- ^ Benedetti (1999a, 182—183).

- ^ Benedetti (1999a, 325, 360) and (2005, 121) and Roach (1985, 197—198, 205, 211—215). The term "Method of Physical Action" was applied to this rehearsal process after Stanislavski's death. Benedetti indicates that though Stanislavski had developed it since 1916, he first explored it practically in the early 1930s; see (1998, 104) and (1999a, 356, 358). Gordon argues the shift in working-method happened during the 1920s (2006, 49—55). Vasili Toporkov, an actor who trained under Stanislavski in this approach, provides in his Stanislavski in Rehearsal (2004) a detailed account of the Method of Physical Action at work in Stanislavski's rehearsals.

- ^ Benedetti (1999a, 355—256), Carnicke (2000, 32—33), Leach (2004, 29), Magarshack (1950, 373—375), and Whyman (2008, 242).

- ^ Quoted by Carnicke (1998, 156). Stanislavski continues: "For in the process of action the actor gradually obtains the mastery over the inner incentives of the actions of the character he is representing, evoking in himself the emotions and thoughts which resulted in those actions. In such a case, an actor not only understands his part, but also feels it, and that is the most important thing in creative work on the stage"; quoted by Magarshack (1950, 375).

- ^ Benedetti (2005, 147-148), Carnicke (1998, 1, 8) and Whyman (2008, 119-120). Not only actors are subject to this confusion; Lee Strasberg's obituary in The New York Times credited Stanislavski with the invention of the Method: "Mr. Strasberg adapted it to the American theatre, imposing his refinements, but always crediting Stanislavsky as his source" (Quoted by Carnicke 1998, 9). Carnicke argues that this "robs Strasberg of the originality in his thinking, while simultaneously obscuring Stanislavsky's ideas" (1997, 9). In a note from 1913 Stanislavski wrote that a character "is sometimes formed psychologically, i.e. from the inner image of the role, but at other times it is discovered through purely external exploration"; quoted by Benedetti (1999a, 216). Neither the tradition that formed in the USSR nor the American Method, Carnicke argues, "integrated the mind and body of the actor, the corporal and the spiritual, the text and the performance as thoroughly or as insistently as did Stanislavsky himself" (1998, 2). For evidence of Strasberg's misunderstanding of this aspect of Stanislavski's work, see Strasberg (2010, 150-151).

- ^ Benedetti (1989, 1) and (2005, 109), Gordon (2006, 40—41), and Milling and Ley (2001, 3—5).

- ^ Benedetti (1989, 1), Gordon (2006, 42—43), and Roach (1985, 204).

- ^ Benedetti (1989, 5).

- ^ Benedetti (1989, 18, 22—23), (1999a, 42), and (1999b, 257), Carnicke (2000, 29), Gordon (2006, 40—42), Leach (2004, 14), and Magarshack (1950, 73—74). As Carnicke emphasises, Stanislavski's early prompt-books, such as that for the production of The Seagull in 1898, "describe movements, gestures, mise en scène, not inner action and subtext" (2000, 29). The principle of a unity of all elements (or what Richard Wagner called a Gesamtkunstwerk) survived into Stanislavski's 'system', while the exclusively external technique did not; although his work shifted from a director-centred to an actor-centred approach, his 'system' nonetheless valorises the absolute authority of the director.

- ^ Milling and Ley (2001, 5). Stanislavski and Nemirovich found they had this practice in common during their legendary 18-hour conversation that led to the establishment of the MAT.

- ^ Bablet (1962, 134), Benedetti (1989, 23—26) and (1999a, 130), and Gordon (2006, 37—42). Carnicke emphasises the fact that Stanislavski's great productions of Chekhov's plays were staged without the use of the 'system' (2000, 29).

- ^ Benedetti (1989, 25—39) and (1999a, part two), Braun (1982, 62—63), Carnicke (1998, 29) and (2000, 21—22, 29—30, 33), and Gordon (2006, 41—45). For an explanation of "inner action", see Stanislavski (1957, 136); for subtext, see Stanislavski (1938, 402—413).

- ^ Benedetti (1989, 30) and (1999a, 181, 185—187), Counsell (1996, 24—27), Gordon (2006, 37—38), Magarshack (1950, 294, 305), and Milling and Ley (2001, 2).

- ^ Carnicke (2000, 13), Gauss (1999, 3), Gordon (2006, 45—46), Milling and Ley (2001, 6), and Rudnitsky (1981, 56).

- ^ Benedetti (1989, 5—11, 15, 18) and (1999b, 254), Braun (1982, 59), Carnicke (2000, 13, 16, 29), Counsell (1996, 24), Gordon (2006, 38, 40—41), and Innes (2000, 53—54).

- ^ Carnicke (1998, 72) and Whyman (2008, 262).

- ^ Milling and Ley (2001, 6).

- ^ Benedetti (1999a, 376-377).

- ^ Milling and Ley (2001, 7) and Stanislavski (1938, 16-36).

- ^ a b Stanislavski (1938, 19)

- ^ Stanislavski (1938, 19). Stanislavski considered the Italian tragedian Tommaso Salvini (1829-1915) to be the finest example of an artist of the school of "experiencing"; see Stanislavski (1938, 19) and Benedetti (1999a, 18)

- ^ Counsell (1996, 25-26). Despite this distinction, however, Stanislavskian theatre, in which actors "experience" their roles, remains "representational" in the broader critical sense; see Stanislavski (1938, 22-27) and the article Presentational acting and Representational acting for a fuller discussion of the different uses of these terms. In addition, for Stanislavski's conception of "experiencing the role" see Carnicke (1998), especially chapter five. While Stanislavski recognises the art of representation as being capable of the creation of genuine works of art, he rejects its technique as "either too showy or too superficial" to be capable of the "expression of deep passions" and the "subtlety and depth of human feelings"; see Stanislavski (1938, 26-27).

- ^ Benedetti (1999a, 169) and Counsell (1996, 27). Many scholars of Stanislavski's work stress that his conception of the "unconscious" (or "subconscious", "superconscious") is pre-Freudian; Benedetti, for example, explains that "Stanislavski merely meant those regions of the mind which are not accessible to conscious recall or the will. It had nothing to do with notions of latent content advanced by Freud, whose works he did not know" (1999a, 169).

- ^ Benedetti (2005, 124) and Counsell (1996, 27).

- ^ Benedetti (1999a, 202, 342).

- ^ Letter to Vera Kotlyarevskaya, 13 July [O.S. 1 July] 1905; quoted by Benedetti (1999a, 168).

- ^ Counsell (1996, 26-27) and Stanislavski (1938, 19)

- ^ Letter to Gurevich, 9 April 1931; quoted by Benedetti (1999a, 338).

- ^ Counsell (1996, 28).

- ^ Counsell (1996, 28).

- ^ Counsell (1996, 28).

- ^ Carnicke (1998, 108).

- ^ Leach (2004, 32) and Magarshack (1950, 322).

- ^ Benedetti (1999a, 202). Benedetti argues that Stanislavski "never succeeded satisfactorily in defining the extent to which an actor identifies with his character and how much of the mind remains detached and maintains theatrical control."

- ^ Stanislavski, quoted by Magarshack (1950, 397).

- ^ Benedetti (1999a, 360). Benedetti emphasises the continuity of the Method of Physical Action with Stanislavski's earlier approaches. Whyman writes that "there is no justification in Stanislavsky's writings for the assertion that the method of physical actions represents a rejection of his previous work" (2008, 247).

- ^ Benedetti (1999a, 356, 358).

- ^ Benedetti (1999a, 359—360), Golub (1998, 1033), Magarshack (1950, 387—391), and Whyman (2008, 136).

- ^ Benedetti (1998, xii) and (1999a, 359—363) and Magarshack (1950, 387—391), and Whyman (2008, 136). Benedetti argues that the course at the Opera-Dramatic Studio is "Stanislavski's true testament". His book Stanislavski and the Actor (1998) offers a reconstruction of the studio's course.

- ^ Carnicke (1998, 1, 167) and (2000, 14), Counsell (1996, 24—25), Golub (1998, 1032), Gordon (2006, 71—72), Leach (2004, 29), and Milling and Ley (2001, 1—2).

- ^ Benedetti (1999a, 354—355), Carnicke (1998, 78, 80) and (2000, 14), and Milling and Ley (2001, 2).

- ^ Whyman (2008, 262).

- ^ Benedetti (1989, 1) and Whyman (2008, 262).

- ^ Counsell (1996, 26).

- ^ Whyman (2008, 109).

- ^ Whyman (2008, 111).

- ^ Whyman (2008, 260-261).

- ^ Magarshack (1950, 389).

- ^ Benedetti (1999a, 302).

- ^ Benedetti (1999a, 154).

- ^ Whyman (2008, 113).

- ^ Quoted by Rudnitsky (1981, 44).

- ^ Rudnitsky (1981, 129).

- ^ Rudnitsky (1981, 140).

- ^ Rudnitsky (1981, 141).

- ^ Benedetti (1999a, 186).

- ^ Stanislavski, quoted by Benedetti (1999a, 232).

- ^ Carnicke (1998, 121).

- ^ Stanislavski (1950, 91).

- ^ Quoted from an interview with Stanislavski (1 May 1914) by Benedetti (1999a, 203); see also Magarshack (1950, 389).

- ^ Benedetti (1999, 204, 266) and Whyman (2008, 134).

- ^ From a note in the Stanislavski archivwefrwqerwqerqWEDQeqwerewrewrewrwrfqewrfwedwdewdwrwerfasdwedweddwadeqwerqde, quoted by Benedetti (1999a, 216).

- ^ Quoted by Benedetti (1999a, 185-186).

- ^ Counsell (1996,26).

Sources edit

- Banham, Martin, ed. 1998. The Cambridge Guide to Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521434378.

- Benedetti, Jean. 1989. Stanislavski: An Introduction. Revised edition. Original edition published in 1982. London: Methuen. ISBN 0413500306.

- ---. 1998. Stanislavski and the Actor. London: Methuen. ISBN 0413711609.

- ---. 1999a. Stanislavski: His Life and Art. Revised edition. Original edition published in 1988. London: Methuen. ISBN 0413525201.

- ---. 1999b. "Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre, 1898-1938." In Leach and Borovsky (1999, 254-277).

- ---. 2005. The Art of the Actor: The Essential History of Acting, From Classical Times to the Present Day. London: Methuen. ISBN 0413773361.

- ---. 2008. Foreword. In Stanislavski (1938, xv-xxii).

- Carnicke, Sharon M. 1998. Stanislavsky in Focus. Russian Theatre Archive Ser. London: Harwood Academic Publishers. ISBN 9057550709.

- ---. 2000. "Stanislavsky's System: Pathways for the Actor". In Hodge (2000, 11-36).

- Chamberlain, Franc. 2000. "Michael Chekhov on the Technique of Acting: 'Was Don Quixote True to Life?'" In Hodge (2000, 79-97).

- Counsell, Colin. 1996. Signs of Performance: An Introduction to Twentieth-Century Theatre. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415106435.

- Gauss, Rebecca B. 1999. Lear's Daughters: The Studios of the Moscow Art Theatre 1905-1927. American University Studies ser. 26 Theatre Arts, vol. 29. New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 0820441554.

- Hobgood, Burnet M. 1991. "Stanislavsky's Preface to An Actor Prepares". Theatre Journal 43: 229-232.

- Hodge, Alison, ed. 2000. Twentieth-Century Actor Training. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415194520.

- Innes, Christopher, ed. 2000. A Sourcebook on Naturalist Theatre. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415152291.

- Leach, Robert. 2004. Makers of Modern Theatre: An Introduction. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415312418.

- Leach, Robert, and Victor Borovsky, eds. 1999. A History of Russian Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. ISBN 0521432200.

- Magarshack, David. 1950. Stanislavsky: A Life. London and Boston: Faber, 1986. ISBN 0571137911.

- Markov, Pavel Aleksandrovich. 1934. The First Studio: Sullerzhitsky-Vackhtangov-Tchekhov. Trans. Mark Schmidt. New York: Group Theatre.

- Milling, Jane, and Graham Ley. 2001. Modern Theories of Performance: From Stanislavski to Boal. Basingstoke, Hampshire and New York: Palgrave. ISBN 0333775422.

- Mirodan, Vladimir. 1997. "The Way of Transformation: The Laban-Malmgren System of Dramatic Character Analysis." Diss. Royal Holloway College, U of London.

- Mitter, Shomit. 1992. Systems of Rehearsal: Stanislavsky, Brecht, Grotowski and Brook. London and NY: Routledge. ISBN 0415067847.

- Moore, Sonia. 1968. Training an Actor: The Stanislavski System in Class. New York: Viking. ISBN 0670002496.

- Pitches, Jonathan. 2006. Science and the Stanislavsky Tradition of Acting. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415329078.

- Ribot, Théodule-Armand. 2006. The Diseases of the Will. Trans. Merwin-Marie Snell. London: Kessinger Publishing's Legacy Reprints. ISBN 1425489982. Online edition available.

- ---. 2007. Diseases of Memory: An Essay in the Positive Psychology. London: Kessinger Publishing's Legacy Reprints. ISBN 1432511645. Online edition available.

- Roach, Joseph R. 1985. The Player's Passion: Studies in the Science of Acting. Theater:Theory/Text/Performance Ser. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472082442.

- Stanislavski, Konstantin. 1936. An Actor Prepares. London: Methuen, 1988. ISBN 0413461904.

- ---. 1938. An Actor’s Work: A Student’s Diary. Trans. and ed. Jean Benedetti. London and New York: Routledge, 2008. ISBN 041542223X.

- ---. 1950. Stanislavsky on the Art of the Stage. Trans. David Magarshack. London: Faber, 2002. ISBN 057108172X.

- ---. 1957. An Actor's Work on a Role. Trans. and ed. Jean Benedetti. London and New York: Routledge, 2010. ISBN 0415461294.

- ---. 1961. Creating a Role. Trans. Elizabeth Reynolds Hapgood. London: Mentor, 1968. ISBN 0450001660.

- ---. 1963. An Actor's Handbook: An Alphabetical Arrangement of Concise Statements on Aspects of Acting. Ed. and trans. Elizabeth Reynolds Hapgood. London: Methuen, 1990. ISBN 0413630803.

- ---. 1968. Stanislavski's Legacy: A Collection of Comments on a Variety of Aspects of an Actor's Art and Life. Ed. and trans. Elizabeth Reynolds Hapgood. Revised and expanded edition. London: Methuen, 1981. ISBN 0413477703.

- Stanislavski, Constantin, and Pavel Rumyantsev. 1975. Stanislavski on Opera. Trans. Elizabeth Reynolds Hapgood. London: Routledge, 1998. ISBN 0878305521.

- Strasberg, Lee. 1987. A Dream of Passion: The Development of the Method. Ed. Evangeline Morphos. New York and London: Penguin. ISBN 0452261988.

- ---. 2010. The Lee Strasberg Notes. Ed. Lola Cohen. Oxon and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415551862.

- Toporkov, Vasily Osipovich. 2001. Stanislavski in Rehearsal: The Final Years. Trans. Jean Benedetti. London: Methuen. ISBN 041375720X.

- Whyman, Rose. 2008. The Stanislavsky System of Acting: Legacy and Influence in Modern Performance. Cambridge: Cambrdige UP. ISBN 9780521886963.