S. A. Andrée's Arctic balloon expedition of 1897 was an effort by Sweden to challenge neighboring Norway in the late 19th-century race to the North Pole. S. A. Andrée, a Swedish patent bureau engineer and ballooning enthusiast, proposed using a hydrogen balloon in order to travel from Svalbard to either Russia or Canada, passing, with luck, straight over the North Pole on the way. Andrée's scheme demonstrated a faith in the power of technology and a disregard for the forces of nature which were extreme even for the period in which he lived. In the opinion of most modern students of the expedition, such attitudes on Andrée's part were major factors in the disastrous course of events and the deaths of Andrée and his two companions.[1]

Andrée failed to be discouraged by many early signs of the dangers and imponderables of his balloon scheme. He considered his trial flights with his own balloon the Svea in Sweden in the mid-1890s as proof that a balloon could be steered by means of his "drag rope" technique, even though he was unable to prevent the prevailing westerly winds from frequently and dangerously blowing the Svea out over the Baltic Sea, and sometimes into it. He engaged the meteorologist and experienced Arctic researcher Nils Gustaf Ekholm to be one of the team, but rejected his advice when Ekholm tested the balloon Örnen (the Eagle) and declared it dangerously leaky.

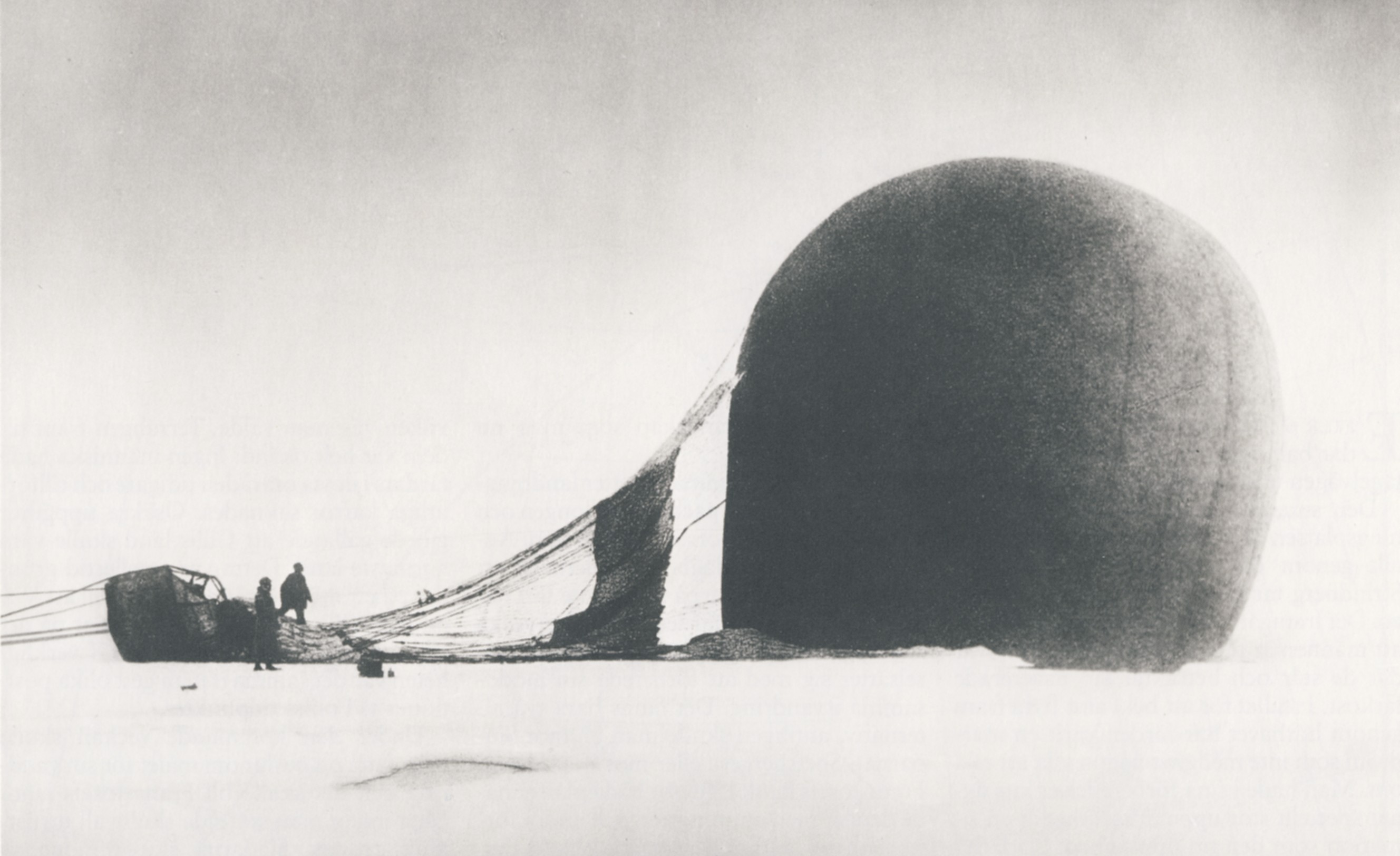

When Andrée took off from Svalbard with his companions Nils Strindberg and Knut Frænkel in July 1897, the balloon lost hydrogen and buoyancy even more quickly than Ekholm had feared and crashed after two days. The explorers were unhurt, but were faced with a gruelling march back to safety. Inadequately clothed, equipped, and prepared, and shocked by the difficulty of the terrain, they did not make it. In spite of heroic efforts they ended up on Kvitøya (=White or White's Island) in Svalbard as the Arctic winter closed in, and died there. For 33 years, until the remains were accidentally found in 1930, the fate of the Andrée expedition remained one of the unsolved riddles of the Arctic. Its solution created a media sensation and a great manifestation of national mourning in Sweden, where the dead men were seen as sacrificing themselves for the ideals of science and the honor of the motherland. More recently, with changing perceptions of the role of the polar areas and the value of indigenous Arctic cultures, Andrée's personal motives have been re-evaluated in less flattering terms. An early example is Per Olof Sundman's bestselling semi-documentary novel of 1967, The Flight of the Eagle, which portrays Andrée not as heroic but as a hostage to his own fundraising campaign, and as pushed by the sponsors and the media into cynically sacrificing the lives of his younger companions along with his own.

S. A. Andrée's scheme

editThe second half of the 19th century has often been called the heroic age of polar exploration.[2] The inhospitable and dangerous Arctic and Antarctic regions spoke powerfully to the Victorian imagination, not as lands with their own ecology and (in the case of the Arctic) cultures, but as challenges to technological ingenuity and manly daring.

The Swede S. A. Andrée shared these enthusiasms, and proposed a plan for letting the wind propel a hydrogen balloon across the Arctic Sea from Svalbard to Bering's Sound, to fetch up in either Alaska, Canada, or Russia, and passing near or even right over the North Pole on the way. Andrée was an engineer at the patent bureau in Stockholm, with an intense interest in technology and inventions and a passion for ballooning. In 1893 he bought his own balloon, the Svea, and made altogether nine journeys with her, starting from Göteborg or Stockholm and travelling a combined distance of 1,500 kilometres.[3] In the prevailing westerly winds, the Svea flights had a strong tendency to carry him uncontrollably out to the Baltic Sea and drag his basket perilously through water and across the many archipelago islands. On one occasion he was blown clear across the Baltic to Finland. His longest trip was from Göteborg due east, across the breadth of Sweden and out over the Baltic to Gotland. Even though he actually saw a lighthouse and heard breakers off Öland, he remained convinced that he was travelling north-east over land, and merely seeing lakes. These voyages were extensively covered by the Stockholm daily newspapers (compare artist's impression, right, of Andrée being blown off an island, from the evening paper Aftonbladet), with a mixture of fascination and raillery.

The main purpose of Andrée's Svea flights was to test and perfect the drag rope steering technique which he had invented and wanted to use on his projected North Pole expedition. Drag ropes, which hang from the balloon basket and drag part of their length on the ground, are designed to counteract the tendency of lighter-than-air craft to travel at the same speed as the wind, a situation which makes steering by sails impossible. The friction of the ropes was intended to slow the balloon to the point where the sails would have an effect (beyond that of making the balloon rotate on its axis). Andrée claimed that, with the drag rope/sails steering, his Svea had essentially become a dirigible, but this is discounted by modern balloonists. The Swedish ballooning association ascribes Andrée's conviction that he could make the Svea diverge from the wind direction by up to 30° entirely to wishful thinking, capricious winds, and the fact that much of the time Andrée was inside cloud and had little idea where he was or which way he was moving.[4] Persistently, too, drag ropes would snap, fall off, become entangled in one another, or get stuck on the ground, which could result in pulling the often low-flying balloon down into a dangerous bounce. No modern Andrée researcher has expressed any faith in drag ropes as a balloon steering technique.

Andrée had some experience of Arctic conditions, having been a junior member of a Swedish geophysical expedition to Spitsbergen in 1882—83, led by Nils Gustaf Ekholm. Ekholm would later join Andrée's Arctic balloon team, only to leave it again before the expedition got off the ground.

Promotion and fundraising

editThe Arctic ambitions of the northern European nation of Sweden were still unrealized, in contrast with neighboring Norway, which was a world power in Arctic exploration through the pioneering voyages of Fridtjof Nansen.[5] The Swedish political and scientific elite and to some extent the whole nation were eager to see Sweden take that lead among the Scandinavian countries which seemed her due, and Andrée, a persuasive speaker and fundraiser, found it unexpectedly easy to gain support for his ideas.[6] At a lecture to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, he took that distinguished audience by storm. The all-important balloon, Andrée emphasized, needed to fulfill four conditions:

- It must have enough lifting power to carry three people and all their scientific, especially photographic, equipment, provisions for four months, and ballast, altogether about 3,000 kg.

- It must be tightly-sealed enough to stay aloft for 30 days.

- The hydrogen gas must be manufactured, and the balloon filled, at the Arctic launch site itself.

- It must be at least somewhat steerable.

Andrée gave a glowingly optimistic account of the ease with which these requirements could be met. Even larger balloons had been constructed in France, he claimed, and more airtight, too. Some French balloons had remained hydrogen-filled for over a year without appreciable loss of buoyancy and without topping-up. As for the hydrogen, filling the balloon at the launch site could easily be done with the help of mobile hydrogen manufacturing units, and for the steering, he referred to his own drag-rope experiments with the Svea, stating that a deviation of 27° could be routinely achieved.

Andrée also told the audience confidently that Arctic summer conditions were exceptionally suitable for ballooning. The midnight sun would enable observations round the clock, halving the voyage time required, and do away with all need for anchoring at night, which might be a dangerous business; nor, with constant daylight, would the balloon's buoyancy be adversely affected by the cold of night. The drag-rope steering technique was particularly well adapted for a region where the ground is "low in friction and free of vegetation", in other words consists of ice. The minimal precipitation in the area posed no threat of weighing down the balloon; if, against expectation, some rain or snow fell, Andrée argued, "precipitation at above-zero temperatures will melt, and precipitation at below-zero temperatures will blow off, for the balloon will be travelling more slowly than the wind." The audience was convinced by these arguments, so disconnected from the realities of the Arctic summer storms, fogs, high humidity, and ever-present threat of ice formation. The societies also approved Andrée's expense calculation of 130,800 kronor, of which the single largest sum, 36,000, was for purchasing the balloon itself. With that approval, there was a rush to support him, headed by Swedish King Oscar II, who personally contributed 30,000 kronor, and Alfred Nobel, the dynamite magnate and founder of the Nobel Prize.[7] Andrée negotiated with the well-known aeronaut and balloon bulder Henri Lachambre in Paris, world capital of ballooning, and ordered a varnished three-layer silk balloon, 20.5 m in diameter, from his workshop. The balloon, originally called North Pole, was to be renamed Örnen, meaning the Eagle.

The balloon team

editFor his 1896 attempt to launch his balloon Örnen (the Eagle), Andrée had many eager volunteers from which to build his desired three-man team, always assumed to include himself. He picked an experienced Arctic meteorological researcher, Nils Gustaf Ekholm (1848—1923), formerly his boss at the Spitsbergen geophysical expedition, and Nils Strindberg (1872—1897), a photographer and constructor of specialized photographic equipment. This was a team with many useful scientific and technical skills, but lacking any notable physical prowess or training for survival under extreme conditions. All three were indoor types, and only one of them, Strindberg, was young. Andrée expected a sedentary voyage, and strength and survival skills were far down on his list. While the expedition waited at Danskøya in Svalbard in the summer of 1896 for southerly winds, which never came, Ekholm became convinced by his checks and measurements of the Eagle balloon that it was too leaky and the undertaking altogether too dangerous, and left the expedition.

Andrée was forced to call off the 1896 attempt because of the persistenly northerly wind, and after this demonstration of the vulnerability of the scheme, enthusiasm for joining the expedition for a second attempt in 1897 did not run quite so high. There were still candidates, however, and Andrée picked out the 27-year-old engineer Knut Frænkel (1870—1897). The team that actually took off on July 11, 1897, consisted of Andrée, Frænkel, and Strindberg.

Knut Frænkel was a civil engineer from the north of Sweden, an athlete and outdoorsman, fond of long mountain hikes. He was enrolled specifically to take over Ekholm's meteorological observations, and, without any of Ekholm's theoretical and scientific knowledge, nevertheless handled this task efficiently. His meteorological journal allows the movements of the three men during their last few months to be reconstructed with considerable exactness.

Nils Strindberg was 24 in 1896. His diary during the death trek of 1897 has the form of messages to his fiancee Anna Charlier, and provides a more emotional and personal window on events than Andrée's own "main diary". Strindberg was doing original research in physics and chemistry, and was especially interested in photography, from practical, aesthetic, and theoretical angles, having both constructed cameras and taken a lot of well-designed amateur photos, as well as gone into the theoretical principles of color photography in his research. He was considered a brilliant student.[8] Several friends and relatives attempted to persuade Strindberg to follow suit when Eklund withdrew, especially after he became engaged in the autumn of 1896, but he declared his faith in Andrée to be unbroken.[9]

- ^ Sven Lundström, passim.

- ^ For instance in the title of John Maxtone-Graham's popularized narrative Safe Return Doubtful: The Heroic Age of Polar Exploration, which has a chapter on the Andrée expedition.

- ^ The most complete account of the Svea voyages is at "Andrées färder".

- ^ "Andrées färder".

- ^ This section is based on Sven Lundström's Vår position är ej synnerligen god, pp. 19—44.

- ^ Lundström, pp. ??

- ^ Lundström, pp. 21—27.

- ^ Lundström, p. 36.

- ^ Lundström, p. 38.