Shakespeare's Sonnet 37 returns to a number of themes sounded in the first 25 of the cycle, such as the effects of age and recuperation from age, and the blurred boundaries between lover and beloved. However, the tone is more complex than in the earlier poems: after the betrayal treated in Sonnets 34–36, the speaker does not return to a simple celebration.

| Sonnet 37 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

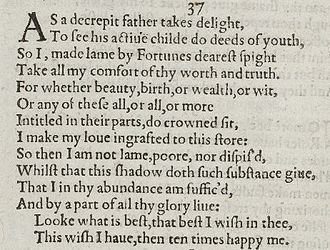

Sonnet 37 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Just as an aged father takes delight in the youthful actions of his son, so I, crippled by fortune, take comfort in your worth and faithfulness. For whether it's beauty, noble birth, wealth, or intelligence, or all of these, or all of these and more, that you possess, I attach my love to it (whatever it is), and as a result I am no longer poor, crippled, or despised. Your mere shadow (present in me) provides such solid reality to me that I am complete with it. I wish whatever is best in you, and if this wish is granted, then I will be extremely happy.

Structure

editSonnet 37 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. The English sonnet is constructed with three quatrains and a final rhyming couplet. The poem follows the form's typical rhyme scheme, ABAB CDCD EFEF GG, and like other Shakespearean sonnets is written in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions per line. The second line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / To see his active child do deeds of youth, (37.2)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

Source and analysis

editThe sonnet was at one point a favorite of biographically oriented critics, such as Edward Capell, who saw in the opening lines a reference either to a physical debility or to Shakespeare's son. This interpretation was rejected by Edmond Malone and others; Horace Howard Furness, discussing it in conjunction with the legend that Shakespeare played Adam in As You Like It, calls the supposition "monstrous." Edward Dowden notes that lameness is used symbolically (as in Coriolanus 4.7.7) to indicate weakness or contemptibility. George Wyndham and Henry Charles Beeching are among the editors who find other analogues for "lame" in this metaphorical sense.

"Dearest" (3) is glossed by Gervinus as "heartfelt", but Malone's gloss "most operative" is generally accepted.

Line 7 has been much discussed. Malone's emendation of "their" to "thy" is no longer accepted. George Steevens, finding an analogy in The Rape of Lucrece, glosses it as "entitled (ie, ennobled) by these things." Nicolaus Delius has it "established in thy gifts, with right of possession." Sidney Lee has "ennobled in thee", reversing the relationship between beloved and "parts." It is commonly agreed that the image is drawn from heraldry.

"Shadow" and "substance" are drawn from Renaissance Neoplatonism; Stephen Booth notes that the wit of line 10 derives from Shakespeare's reversal of the usual relationship between reality and reflection.

Notes

edit- ^ Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

References

edit- Baldwin, T. W. On the Literary Genetics of Shakspeare's Sonnets. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1950.

- Hubler, Edwin. The Sense of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952.

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485. — Volume I and Volume II at the Internet Archive

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. Arden Shakespeare, third series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951. — 1st edition at the Internet Archive

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

External links

edit- Works related to Sonnet 37 (Shakespeare) at Wikisource

- Analysis