Sofonisba Anguissola (c. 1532[1] – 16 November 1625), also known as Sophonisba Angussola or Sophonisba Anguisciola,[2][3] was an Italian Renaissance painter born in Cremona to a relatively poor noble family. She received a well-rounded education that included the fine arts, and her apprenticeship with local painters set a precedent for women to be accepted as students of art. As a young woman, Anguissola traveled to Rome where she was introduced to Michelangelo, who immediately recognized her talent, and to Milan, where she painted the Duke of Alba. The Spanish queen, Elizabeth of Valois, was a keen amateur painter and in 1559 Anguissola was recruited to go to Madrid as her tutor, with the rank of lady-in-waiting. She later became an official court painter to the king, Philip II, and adapted her style to the more formal requirements of official portraits for the Spanish court. After the queen's death, Philip helped arrange an aristocratic marriage for her. She moved to Sicily, and later Pisa and Genoa, where she continued to practice as a leading portrait painter.

Sofonisba Anguissola | |

|---|---|

Self-Portrait, 1556, Lancut Museum, Poland | |

| Born | c. 1532 |

| Died | 16 November 1625 (aged 93) |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Education | Bernardino Campi, Bernardino Gatti |

| Known for | Portrait painting, drawing |

| Movement | Late Renaissance |

| Patron(s) | Philip II of Spain |

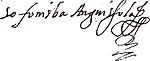

| Signature | |

| |

Her most distinctive and attractive paintings are her portraits of herself and her family, which she painted before she moved to the Spanish court. In particular, her depictions of children were fresh and closely observed. At the Spanish court she painted formal state portraits in the prevailing official style, as one of the first, and most successful, of the relatively few female court painters. Later in her life she also painted religious subjects, although many of her religious paintings have been lost. In 1625, she died at age 93 in Palermo.

Anguissola's example, as much as her oeuvre, had a lasting influence on subsequent generations of artists, and her great success opened the way for larger numbers of women to pursue serious careers as artists. Her paintings can be seen at galleries in Boston (Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum), Milwaukee (Milwaukee Art Museum), Bergamo, Brescia, Budapest, Madrid (Museo del Prado), Naples, and Siena, and at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence.

Her contemporary Giorgio Vasari wrote that Anguissola "has shown greater application and better grace than any other woman of our age in her endeavors at drawing; she has thus succeeded not only in drawing, coloring and painting from nature, and copying excellently from others, but by herself has created rare and very beautiful paintings."[4]

Family

editThe origin and the name of the noble Anguissola family are linked to an ancient Byzantine tradition, rich in historical details.[5]

According to this tradition, the Anguissolas are descended from the Constantinopolitan warlord Galvano Sordo or Galvano de Soardi/Sourdi (Σούρδη, a family name still in use today in Greece, Constantinople and Smyrna).[6] In 717, Galvano served in the army of the Byzantine emperor Leo III the Isaurian, and "with an ingenious artificial fire, contributed to liberate the city of Constantinople from the Saracens who had kept it besieged by land and sea".[7] This "artificial fire" was the so-called Greek fire, an incendiary weapon developed in the late 7th century, which was responsible for many key Byzantine military victories, most notably the salvation of Constantinople from two Arab sieges, thus securing the Empire's survival.

Since the shield of the Sourdi carried the effigy of an asp (in Latin: anguis),[9] after Galvano's victory over the Umayyads, his brothers-in-arms and the people of Constantinople exclaimed: "Anguis sola fecit victoriam!", i.e.: "The snake alone brought the victory!" This saying became very popular, and Galvano himself was nicknamed "Anguissola". The emperor eventually bestowed the Anguissola surname to all his descendants.[10][5] In this regard, it has been suggested that the monogram depicted on Anguissola's miniature self-portrait may contain the family motto "Anguis sola fecit victoriam"[11] or, more simply, the name of Anguissola's father, Amilcare.

Fleeing from a pestilence that raged in Constantinople, the descendants of the first Anguissola settled in Italy, intermarried with other noble families such as the Komnenoi, the Gonzagas, the Caracciolos, the Scottis and the Viscontis, and built autonomous estates in Piacenza, Cremona, Vicenza and other regions of Italy. The Anguissolas who settled in Venice belonged to the patriciate of that city from 1499 to 1612.

Childhood and training

editSofonisba Anguissola was born into a poor but noble family in Cremona, Lombardy in 1532, the oldest of seven children, six of whom were girls.[12] Her father, Amilcare Anguissola, was a member of the Cremonese nobility, and her mother, Bianca Ponzone, was also of noble background. The family lived near the site of a famous 2nd century B.C. battle, the battle of the Trebbia, between Romans and Carthaginians, and several members of the Anguissola family were named after ancient Carthaginian historical characters: Amilcare was named for the Carthaginian general Hamilcar Barca; he named his first daughter after the tragic Carthaginian figure Sophonisba and his only son Asdrubale after the warlord Hasdrubal Barca.[13] Amilcare Anguissola, inspired by Baldassare Castiglione's book Il Cortigiano, encouraged all his daughters (Sofonisba, Elena, Lucia, Europa, Minerva and Anna Maria) to cultivate and perfect their talents. Four of the sisters (Elena, Lucia, Europa and Anna Maria) became painters, but Sofonisba was by far the most accomplished and renowned and taught her younger siblings.[12] Elena Anguissola (c. 1532 – 1584) abandoned painting to become a nun. Both Anna Maria and Europa gave up art upon marrying, while Lucia Anguissola (1536 or 1538 – c. 1565–1568), the best painter of Sophonisba's sisters, died young. The remaining sister, Minerva, became a writer and Latin scholar. Asdrubale, Sophonisba's brother, studied music and Latin, but not painting.

Her aristocratic father made sure that Anguissola and her sisters received a well-rounded education that included the fine arts. Anguissola was fourteen when her father sent her and her sister Elena to study with Bernardino Campi, a respected portrait and religious painter of the Lombard school.[12] When Campi moved to another city, Anguissola continued her studies with painter Bernardino Gatti (known as Il Sojaro), a pupil of Correggio's.[13] Anguissola's apprenticeship with local painters set a precedent for women to be accepted as students of art.[14][15] Dates are uncertain, but Anguissola probably continued her studies under Gatti for about three years (1551–1553).

One of Anguissola's most important early works was Bernardino Campi Painting Sofonisba Anguissola (c. 1550). The unusual double portrait depicts Anguissola's art teacher in the act of painting a portrait of her.[13]

In 1554, at age twenty-two, Anguissola traveled to Rome, where she spent her time sketching various scenes and people. While in Rome, she was introduced to Michelangelo by another painter who was familiar with her work. Anguissola initially showed Michelangelo a drawing of a laughing girl, but the painter challenged her to draw a weeping boy, a subject which he felt would be more challenging.[16] Anguissola drew Boy Bitten by a Crayfish and sent it back to Michelangelo, who immediately recognized her talent.[12] Michelangelo subsequently gave Anguissola sketches from his notebooks to draw in her own style and offered advice on the results. For at least two years, Anguissola continued this informal study, receiving substantial guidance from Michelangelo.[17]

Experiences as a female artist

editAnguissola's education and training had different implications from those of men, since men and women worked in separate spheres. Her training was not to help her into a profession where she would compete for commissions with male artists, but to make her a better wife, companion, and mother.[18] Although Anguissola enjoyed significantly more encouragement and support than the average woman of her day, her social class did not allow her to transcend the constraints of her sex. Without the possibility of studying anatomy or drawing from life (it was considered unacceptable for a lady to view nudes), she could not undertake the complex multi-figure compositions required for large-scale religious or history paintings.

Instead, she experimented with new styles of portraiture, setting subjects informally. Self-portraits and family members were her most frequent subjects, as seen in such paintings as Self-Portrait (1554, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), Portrait of Amilcare, Minerva and Asdrubale Anguissola (c. 1557–1558, Nivaagaards Malerisambling, Nivå, Denmark), and her most famous picture, The Chess Game (1555, Muzeum Narodowe, Poznań), which depicted her sisters Lucia, Minerva and Europa. Painted when Anguissola was 23 years old, The Chess Game is an intimate representation of an everyday family scene, combining elaborate formal clothing with very informal facial expressions, which was unusual for Italian art at this time. The Chess Game explored a new kind of genre painting which places her sisters in a domestic setting instead of the formal or allegorical settings that were popular at the time.[19] This painting has been regarded as a conversation piece, which is an informal portrait of a group engaging in lively conversation or some activity .

Anguissola's self-portraits also offer evidence of what she thought her place was as a woman artist. Normally, men were seen as creative actors and women as passive objects, but in her self-portrait of 1556, Anguissola presents herself as the artist, separating herself from the role as the object to be painted.[20] Additional pieces show how she rebels against the notion that women are objects, in essence an instrument to be played by men. Her self-portrait of 1561 show her playing an instrument, taking on a different role.[21] In her later portraits she represents multiple statuses by using a double portrait image portraying herself as an artist or a wife.[22]

She became well known outside of Italy, and in 1559 King Philip II of Spain asked her to be lady-in-waiting and art teacher to Queen Elisabeth of Valois, who was only 14 at the time. Queen Elisabeth of Valois and Anguissola became good friends, and when the Queen died nine years later, Anguissola left the court because she was so sad. She had painted the entire royal family and even the Pope commissioned Anguissola to do a portrait of the Queen.[24]

At the Spanish Court

editIn 1558, already established as a painter, Anguissola went to Milan, where she painted the Duke of Alba, Fernando Álvarez de Toledo. He in turn recommended her to the Spanish king, Philip II.[25] The following year, Anguissola was invited to join the Spanish Court, which was a turning point in her career.[13]

Anguissola was approximately 26 when she left Italy to join the Spanish court. In the winter of 1559–1560, she arrived in Madrid to serve as a court painter and lady-in-waiting to the new queen, Elisabeth of Valois, Philip's third wife, who was herself an amateur portraitist. Anguissola soon gained Elisabeth's admiration and confidence and spent the following years painting many official portraits for the court, including Philip II's sister, Joanna, and his son, Don Carlos.

These types of painting were far more demanding than the informal portraits upon which Anguissola had based her early reputation, as it took a tremendous amount of time and energy to render the many intricate designs of the fine fabrics and elaborate jewelry associated with royal subjects. Yet despite the challenge, Anguissola's paintings of Elisabeth of Valois – and later of Anne of Austria, Philip II's fourth wife – were vibrant and full of life.

During her 14-year residence, she guided the artistic development of Queen Elisabeth, and influenced the art made by her two daughters, Isabella Clara Eugenia and Catherine Michaela. Anguissola painted a portrait of the King's sister, Margaret of Parma, for Pope Pius IV in 1561 and, after Queen Elisabeth's death in childbirth in 1568, painted the likeness of Anne of Austria, Philip's fourth wife. While she continued painting portraits at the court, the Althorp Self-Portrait is the "only securely attributed work surviving from this period".[26] For the royal family, Anguissola produced detailed scenes of their lives that now hang in the Prado Museum. With the gifts and a dowry of 12,000 scudi she earned along with her salary as court painter and lady-in-waiting to the queen, she amassed an admirable return from her craft.

While in the service of Elisabeth of Valois, Anguissola worked closely with Alonso Sanchez Coello. So closely in fact, that the famous painting of the middle-aged King Philip II was long attributed to Coello or Juan Pantoja de la Cruz. Only recently has Anguissola been recognized as the painting's creator.[27]

Personal life

editAfter the death of Elisabeth of Valois in 1568, Philip II took a special interest in Anguissola's future. He had wished to marry her to one of the nobles in the Spanish Court. In 1571, when she was approaching the age of 40, Anguissola entered an arranged marriage to a Sicilian nobleman chosen for her by the Spanish court.[13] Philip II paid a dowry of 12,000 scudi for her marriage to Fabrizio Moncada Pignatelli, son of the Prince of Paternò, Viceroy of Sicily. Fabrizio was said to be supportive of her painting. Anguissola and her husband left Spain with the king's permission, and are believed to have lived in Paternò (near Catania) from 1573 to 1579, though some recent scholarship has suggested that the couple remained in Spain.[12] She received a royal pension of 100 ducats that enabled her to continue working and tutoring would-be painters. Her private fortune also supported her family and brother Asdrubale following Amilcare Anguissola's financial decline and death. In Paternò she painted and donated "La Madonna dell'Itria".

Anguissola's husband died in 1579 under mysterious circumstances.[13] Two years later, while traveling to Cremona by sea, she fell in love with the ship's captain, sea merchant Orazio Lomellino.[12] Against the wishes of her brother, they married in Pisa on 24 December 1584[28][13] and lived in Genoa until 1620. She had no children, but maintained cordial relationships with her nieces and her stepson, Giulio.

Later years

editLomellino's fortune, plus a generous pension from Philip II, allowed Anguissola to paint freely and live comfortably. By now quite famous, Anguissola received many colleagues who came to visit and discuss the arts with her. Several of these were younger artists, eager to learn and mimic Anguissola's distinctive style.

In her later life, Anguissola painted not only portraits but religious themes, as she had done in the days of her youth, although many of the latter have been lost. She was the leading portrait painter in Genoa until she moved to Palermo in her last years. In 1620 she painted her last self-portrait.

On 12 July 1624, Anguissola was visited by the young Flemish painter Anthony van Dyck, who recorded sketches from his visit to her in his sketchbook.[29] Van Dyck, who believed her to be 96 years of age (she was actually about 92) noted that although "her eyesight was weakened", Anguissola was still mentally alert.[28] Excerpts of the advice she gave him about painting survive from this visit,[30] and he was said to have claimed that their conversation taught him more about the "true principles" of painting than anything else in his life.[2][3] Van Dyck drew her portrait while visiting her. This last portrait made of Anguissola survives on public display at Knole.[31] The next year, she returned to Sicily.

Anguissola became a wealthy patron of the arts after the weakening of her sight.[25] In 1625, she died at age 93 in Palermo.

Anguissola's adoring second husband, who described her as small of frame, yet "great among mortals", buried her with honor in Palermo at the Church of San Giorgio dei Genovesi. Seven years later, on the anniversary of what would have been her 100th birthday, her husband placed an inscription on her tomb that read in part:

To Sofonisba, my wife, who is recorded among the illustrious women of the world, outstanding in portraying the images of man. Orazio Lomellino, in sorrow for the loss of his great love, in 1632, dedicated this little tribute to such a great woman.

— Orazio Lomellino, Inscription on Anguissola's tomb.[32]

Style

editThe influence of Campi, whose reputation was based on portraiture, is evident in Anguissola's early works, such as the Self-Portrait (Florence, Uffizi). Her work was akin to the worldly tradition of Cremona, influenced greatly by the art of Parma and Mantua, in which even religious works were imbued with extreme delicacy and charm. From Gatti she seems to have absorbed elements reminiscent of Correggio, beginning a trend in Cremonese painting of the late 16th century. This new direction is reflected in Lucia, Minerva and Europa Anguissola Playing Chess (1555; Poznań, N. Mus.) in which portraiture merges into a quasi-genre scene, a characteristic derived from Brescian models.

The main body of Anguissola's earlier work consists of self-portraits (the many "autoritratti" reflect the fact that portraits of her were frequently requested due to her fame) and portraits of her family, which are considered by many to be her finest works.

Approximately fifty works have been attributed to Anguissola. Her paintings can be seen at galleries in Baltimore (Walters Art Museum), Bergamo, Berlin (Gemäldegalerie), Graz (Joanneum Alte Galerie), Madrid (Museo del Prado), Milan (Pinacoteca di Brera), Milwaukee (Milwaukee Art Museum), Naples (National Museum of Capodimonte), Poznań (National Museum, Poznań), Siena (Pinacoteca Nazionale), Southampton (City Art Gallery), and Vienna (Kunsthistorisches Museum).

Works

editHistorical significance

editSofonisba Anguissola's oeuvre had a lasting influence on subsequent generations of artists. Her portrait of Queen Elisabeth of Valois with a zibellino (the pelt of a marten set with a head and feet of jewelled gold) was widely copied by many of the finest artists of the time, such as Peter Paul Rubens, while Caravaggio allegedly took inspiration from Anguissola's work for his Boy Bitten by a Lizard.[16]

Anguissola is significant to feminist art historians. Although there has never been a period in Western history in which women were completely absent in the visual arts, Anguissola's great success opened the way for larger numbers of women to pursue serious careers as artists; Lavinia Fontana expressed in a letter written in 1579 that she and another woman, Irene di Spilimbergo, had "set [their] heart[s] on learning how to paint" after seeing one of Anguissola's portraits.[33] Some of her more well-known successors include Lavinia Fontana, Barbara Longhi, Fede Galizia and Artemisia Gentileschi.

A Cremonese school bears the name Liceo Statale Sofonisba Anguissola.[34]

American artist Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827) named his daughter Sophonisba Angusciola (1786–1859; married name Sellers). She became a painter and a quilter whose works are in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Crater

editOn 4 August 2017 a crater on Mercury was named after her.[35]

Recent exhibits

edit- 2019-2020: Anguissola, along with Lavinia Fontana, was the focus of a major exhibit entitled "A Tale of Two Women Painters" at the Museo del Prado, Madrid.[36]

- 2022: "Sofonisba – History's forgotten miracle" in the Nivaagaard Malerisamling [37]

- 2023: "Sofonisba Anguissola" in Rijksmuseum Twenthe [38]

- 2023-2024: Anguissola is featured in the exhibit "Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400-1800"[39]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Great women artists. Phaidon Press. 2019. p. 35. ISBN 978-0714878775.

- ^ a b EB (1878).

- ^ a b EB (1911).

- ^ Vasari. p. 36

- ^ a b "Anguissola – EFL – Società Storica Lombarda".

- ^ Gamberini, Cecilia (2016). Barker, Sheila (ed.). Sofonisba Anguissola at the Court of Philip II. Brepols. pp. 29–38. ISBN 978-1-909400-35-1.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Schroeder, Franz (1830). Repertorio genealogico delle famiglie confermate nobili e dei titolati nobili esistenti nelle provincie venete... (in Italian). Alvisopoli. p. 32.

- ^ "Self-Portrait; Sofonisba Anguissola (Italian (Cremonese), about 1532–1625); Italian; about 1556". Boston: Museum of Fine Arts. Accession number 60.155.

- ^ "Anguissola – EFL – Società Storica Lombarda". servizi.ct2.it (in Italian). Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- ^ "ANGUISSOLA in "Enciclopedia Italiana"".

- ^ Costa, Patrizia (1999). "Sofonisba Anguissola's Self-portrait in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts". Arte Lombarda. 125 (1): 54–62. JSTOR 43132413.

- ^ a b c d e f "Sofonisba Anguissola | Biography, Art, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Life and Works of Sofonisba Anguissola, Noblewoman, Portraitist of Philip II". Hubpages. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ Greer, Germaine (1978), The Obstacle Race: The Fortunes of Women Painters and Their Work, New York: Farrar, p. 180

- ^ Glenn, Sharlee Mullins (1990), "Sofonisba Anguissola: History's Forgotten Prodigy", Women's Studies, 18 (2/3): 296, doi:10.1080/00497878.1990.9978837

- ^ a b "Michelangelo Buonarroti and his women". The Florentine. 2 November 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ "Sofonisba Anguissola: Late Renaissance | Unspoken Artists". sites.psu.edu. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ Sylvia Ferino-Pagden and Maria Kusche, Sofonisba Anguissola: A Renaissance Woman, (Washington D.C.: The National Museum of Women in the Arts, 1995).

- ^ Rozsika, Parker; Pollock, Griselda (29 October 1981). Old mistresses : women, art, and ideology. London. ISBN 0710008791. OCLC 8160325.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Mary Garrard, "Here's Looking at Me: Sofonisba Anguissola and the Problem of the Woman Artist," Renaissance Quarterly 47, no. 3:(1994): 556.

- ^ Mary Garrard, "Here's Looking at Me: Sofonisba Anguissola and the Problem of the Woman Artist," Renaissance Quarterly 47, no. 3:(1994): 557.

- ^ Cheney, Liana De Girolami (1993). "Review of Sofonisba Anguissola: The First Great Woman Artist of the Renaissance". The Sixteenth Century Journal. 24 (4): 942–947. doi:10.2307/2541628. ISSN 0361-0160. JSTOR 2541628.

- ^ "Portrait of Marquess Massimiliano Stampa".

- ^ Weidemann, Christiane; Larass, Petra; Klier, Melanie (2008). 50 Women Artists You Should Know. Prestel. pp. 14, 15. ISBN 978-3-7913-3956-6.

- ^ a b "Sofonisba Anguissola". www.oneonta.edu. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ Marco Tanzi. "Anguissola." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 14 February 2017. subscription required

- ^ Museo del Prado, Catálogo de las pinturas, 1996, p. 7, Ministerio de Educación y Cultura, Madrid, ISBN 84-87317-53-7

- ^ a b Tanzi, Marco. "Anguissola." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ Jaffé, Michael. "Dyck, Anthony van." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ^ Adriani, Gert (1940). Anton Van Dyck: Italienisches Skizzenbuch. Vienna.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Barnes, Susan (2004). Van Dyck: A Complete Catalogue of the Paintings. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-300-09928-7.

- ^ "The High Priestess: Description". 78 Friends. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012.

- ^ Jacobs, Frederika H. (1994). "Woman's Capacity to Create: The Unusual Case of Sofonisba Anguissola". Renaissance Quarterly. 47 (1): 74–101. doi:10.2307/2863112. JSTOR 2863112. S2CID 162701161.

- ^ "Sofonisba Anguissola Facts". biography.yourdictionary.com. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- ^ "Planetary Names: Crater, craters: Anguissola on Mercury".

- ^ "A Tale of Two Women Painters: Sofonisba Anguissola and Lavinia Fontana - Exhibition - Museo Nacional del Prado". www.museodelprado.es.

- ^ "Sofonisba – History's forgotten miracle".

- ^ "Sofonisba Anguissola".

- ^ Banta, Andaleeb Badiee, Alexa Greist, and Theresa Kutasz Christensen, eds. Making her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400-1800. Toronto, Ontario: Goose Lane Editions, 2023. Published in conjunction with an exhibition of the same title, organized by and presented at the Baltimore Museum of Art, October 1, 2023-January 7, 2024 and the Art Gallery of Ontario, March 30, 2024-July 1, 2024.

Bibliography

edit- Baynes, T. S., ed. (1878), , Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 2 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, p. 47

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), , Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 2 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 44

- Chadwick, Whitney (1990). Women, Art, and Society. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-20354-5.

- Ferino-Pagden, Sylvia; Kusche, Maria (1995). Sofonisba Anguissola: A Renaissance Woman. National Museum of Women in the Arts. ISBN 978-0-940979-31-4.

- Harris, Ann Sutherland; Nochlin, Linda (1976). Women Artists: 1550–1950. New York: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-41169-9.

- Perlingieri, Ilya Sandra (1992). Sofonisba Anguissola: The First Great Woman Artist of the Renaissance. Rizzoli International. ISBN 978-0-8478-1544-9.

- Pizzagalli, Daniela (2003). La signora della pittura: vita di Sofonisba Anguissola, gentildonna e artista nel Rinascimento [The Lady of the Painting: The Life of Sofonisba Anguissola, Gentlewoman and Artist of the Renaissance] (in Italian). Milan: Rizzoli. ISBN 978-88-17-99509-2.

Further reading

edit- Caroli, Flavio (1987). Sofonisba Anguissola e le sue sorelle (in Italian). Milan: Mondadori. ISBN 9788804300892.

- de Tolnay, Charles (1941). "Sofonisba Anguissola and her relations with Michelangelo". Journal of the Walters Art Gallery. IV: 115–119.

- Garrard, Mary (1994). "Here's looking at me: Sofonisba Anguissola and the problem of the woman artist". Renaissance Quarterly. 47 (3): 556–622. doi:10.2307/2863021. JSTOR 2863021.

- Giordano, Francesco (29 June 2006). "Sofonisba Anguissola: una vita per la pittura". I Paternesi de La Sicilia. Catania.

- Giordano, Francesco (2008). "Sofonisba Anguissola a Paternò". Ricerche-C.R.E.S. Centro di Ricerca Economica e Scientifica. 12 (1). Catania.

- Glenn, Sharlee Mullins (November 1990). "Sofonisba Anguissola: History's forgotten prodigy". Women's Studies. 18 (2–3). Gordon and Breach, Science Publishers S.A.: 295–308. doi:10.1080/00497878.1990.9978837. ISSN 0049-7878.

- Jacobs, Fredrika (Spring 1994). "Woman's capacity to create: The unusual case of Sofonisba Anguissola". Renaissance Quarterly. 47 (1): 74–101. doi:10.2307/2863112. JSTOR 2863112.

- Nicholson, Elizabeth S. G.; Price, Rebecca; McAllister, Jane; Peterfreund, Karen I., eds. (2007). Italian Women Artists from Renaissance to Baroque. Milan: Skira. pp. 106–121. ISBN 9788876249198.

- Pagden, Sylvia Ferino; Kusche, Maria (1995). Sofonisba Anguissola: A Renaissance Woman. Washington, DC: National Museum of Women in Arts. ISBN 0940979314. – exhibition catalog

Novels based on her life

edit- Boullosa, Carmen (2008). La virgen y el violín [The Virgin and the Violin] (in Spanish). Madrid: Editorial Siruela. ISBN 9788498411898. – a novel on Sofonisba Anguissola's life

- DiGiuseppe, Donna (2019). Lady in Ermine — The Story of a Woman Who Painted The Renaissance: A Biographical Novel of Sofonisba Anguissola. Tempe, AZ: Bagwin Books. ISBN 978-0-86698-821-6.

- Montani, Chiara (2018). Sofonisba I ritratti dell'anima (in Italian). Lurago d'Erba: Il Ciliegio. ISBN 9788867715510.

- Pierini, Giovanna (2018). La dama con il ventaglio (in Italian). Milano: Electa. ISBN 9788891811776.

- Vihos, Lisa (2022). The Lone Snake: The Story of Sofonisba Anguissola. Sheboygan, WI: Water's Edge Press. ISBN 978-1-952526-10-7.

External links

edit- Original text mentioning her from 1568 edition with illustration of Properzia de' Rossi by Giorgio Vasari on Italian Wikisource

- Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

- ArtCyclopedia

- The Kress Foundation

- El País archivo