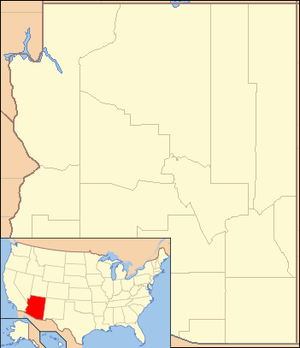

Saguaro National Park is a United States national park in Pima County, southeastern Arizona. The 92,000-acre (37,000 ha) park consists of two separate areas—the Tucson Mountain District (TMD), about 10 miles (16 km) west of Tucson, and the Rincon Mountain District (RMD), about 10 miles (16 km) east of the city. Both districts preserve Sonoran Desert landscapes, fauna, and flora, including the giant saguaro cactus.

| Saguaro National Park | |

|---|---|

Sunset in the Rincon Mountain District of the park | |

| Location | Tucson, Arizona, Pima, Arizona, United States |

| Coordinates | 32°10′45″N 110°44′13″W / 32.17917°N 110.73694°W |

| Area | 91,716 acres (371.16 km2)[1] |

| Established | March 1, 1933 as a national monument October 14, 1994 as a national park[2] |

| Named for | Saguaro, a cactus |

| Visitors | 908,194 (in 2022)[3] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Saguaro National Park |

The volcanic rocks on the surface of the Tucson Mountain District differ greatly from the surface rocks of the Rincon Mountain District; over the past 30 million years, crustal stretching displaced rocks from beneath the Tucson Mountains of the Tucson Mountain District to form the Rincon Mountains of the Rincon Mountain District. Uplifted, domed, and eroded, the Rincon Mountains are significantly higher and wetter than the Tucson Mountains. The Rincons, as one of the Madrean Sky Islands between the southern Rocky Mountains and the Sierra Madre Oriental in Mexico, support high biodiversity and are home to many plants and animals that do not live in the Tucson Mountain District.

Earlier residents of and visitors to the lands in and around the park before its creation included the Hohokam, Sobaipuri, Tohono O'odham, Apaches, Spanish explorers, missionaries, miners, homesteaders, and ranchers. In 1933, President Herbert Hoover used the power of the Antiquities Act to establish the original park, Saguaro National Monument, in the Rincon Mountains. In 1961, President John F. Kennedy added the Tucson Mountain District to the monument and renamed the original tract the Rincon Mountain District. The United States Congress combined the Tucson Mountain District and the Rincon Mountain District to form the national park in 1994.

Popular activities in the park include hiking on its 165 miles (266 km) of trails and sightseeing along paved roads near its two visitor centers. Both districts allow bicycling and horseback riding on selected roads and trails. The Rincon Mountain District offers limited wilderness camping, but there is no overnight camping in the Tucson Mountain District.

Names edit

The park gets its name from the saguaro (Carnegiea gigantea),[4] a large cactus that is native to the Sonoran Desert and that does not grow naturally elsewhere.[5] Rincón—as in Rincon Mountains, Rincon Creek, and Rincon Valley—is Spanish for corner[6] and refers to the shape of the mountain range and its footprint.[7] The name Tucson derives from Papago-Piman words cuk ṣon [ˡtʃukʂɔn], meaning dark spring or brown spring.[8] Tank or Tanque refers to a small artificial pool behind a dam that traps runoff in an existing natural depression.[9] Madrean derives from Madre in Sierra Madre[10] (Mother Mountains[11]).

Geography edit

The park consists of two separate parcels, the Tucson Mountain District (TMD) to the west of Tucson, Arizona, and the Rincon Mountain District (RMD) to the east. Each parcel comes within about 10 miles (16 km) of the center of the city.[12] Their total combined area in 2016 was 91,716 acres (37,116 ha).[1] The Tucson Mountain District covers about 25,000 acres (10,000 ha),[13] while the much larger Rincon Mountain District accounts for the balance of about 67,000 acres (27,000 ha).[14] About 71,000 acres (29,000 ha) of the park, including large fractions of both districts, is designated wilderness.[15]

Interstate 10, the major highway nearest to the park, passes through Tucson.[16] Tucson Mountain Park abuts the south side of the Tucson Mountain District, and to its west lies the Avra Valley.[16] The Rincon Mountain Wilderness, a separate protected area of about 37,000 acres (15,000 ha)[17] in the Coronado National Forest,[18] abuts the Rincon Mountain District on the east and southeast, while the Rincon Valley lies immediately south of the western part of the Rincon Mountain District.[16]

Both districts conserve tracts of the Sonoran Desert, including ranges of significant hills, the Tucson Mountains in the west and the Rincon Mountains in the east.[4] Elevations in the Tucson Mountain District range from 2,180 to 4,687 feet (664 to 1,429 m),[4] the summit of Wasson Peak.[19] Elevations within the Rincon Mountain District vary from 2,670 to 8,666 feet (814 to 2,641 m)[4] at the summit of Mica Mountain.[20]

Saguaro National Park lies within the watershed of the north-flowing Santa Cruz River,[21] which is generally dry.[22] Rincon Creek in the southern part of the Rincon Mountain District, free-flowing for at least part of the year, has the largest riparian zone in the park. The creek is a tributary of Pantano Wash, which crosses Tucson from southeast to northwest to meet Tanque Verde Wash. The two washes form the Rillito River, another dry wash,[6] an east–west tributary of the Santa Cruz River.[16] The washes in both districts are usually dry but are subject at times to flash floods.[23] Smaller riparian zones are found near springs and tinajas in the Rincon Mountain District.[24] The largest of the springs is at Manning Camp, high in the Rincons.[25]

Climate edit

According to the Köppen climate classification system, Saguaro National Park has a Hot semi-arid climate (BSh). According to the United States Department of Agriculture, the Plant Hardiness zone at Red Hills Visitor Center 2,553 feet (778 m) is 9b with an average annual extreme minimum temperature of 25.8 °F (−3.4 °C), and 9a with an average annual extreme minimum temperature of 23.4 °F (−4.8 °C) at Rincon Mountain Visitor Center 3,091 feet (942 m).[26]

Brief violent summer rains are usually accompanied by lightning, dust storms and flash floods.[27] Some moisture at the highest elevations in the Rincons falls as snow in winter; snowmelt adds to the limited water available at lower elevations later in the year.[28]

Studies of the effects of climate change on the park show that its annual mean temperature rose about 4 °F (2 C) from 1900 to 2010.[29][30] Climate data below is from 2019:

| Climate data for Red Hills Visitor Center, Saguaro National Park. Elev: 2579 ft (786 m) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 66.2 (19.0) |

69.1 (20.6) |

74.8 (23.8) |

83.1 (28.4) |

92.4 (33.6) |

101.1 (38.4) |

101.0 (38.3) |

98.6 (37.0) |

96.1 (35.6) |

86.4 (30.2) |

74.6 (23.7) |

65.4 (18.6) |

84.1 (28.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 53.1 (11.7) |

55.7 (13.2) |

60.5 (15.8) |

67.5 (19.7) |

76.2 (24.6) |

85.1 (29.5) |

87.8 (31.0) |

85.9 (29.9) |

82.4 (28.0) |

72.0 (22.2) |

60.6 (15.9) |

52.3 (11.3) |

70.0 (21.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 39.9 (4.4) |

42.3 (5.7) |

46.2 (7.9) |

51.9 (11.1) |

60.0 (15.6) |

69.1 (20.6) |

74.5 (23.6) |

73.3 (22.9) |

68.7 (20.4) |

57.6 (14.2) |

46.7 (8.2) |

39.1 (3.9) |

55.8 (13.2) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.97 (25) |

0.92 (23) |

0.90 (23) |

0.34 (8.6) |

0.19 (4.8) |

0.30 (7.6) |

1.99 (51) |

2.51 (64) |

1.09 (28) |

0.94 (24) |

0.58 (15) |

1.00 (25) |

11.73 (298) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 40.2 | 37.6 | 31.4 | 23.5 | 19.8 | 17.9 | 31.3 | 40.2 | 33.7 | 30.4 | 33.5 | 40.7 | 31.7 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 29.5 (−1.4) |

30.2 (−1.0) |

30.0 (−1.1) |

28.9 (−1.7) |

31.9 (−0.1) |

36.7 (2.6) |

53.7 (12.1) |

58.9 (14.9) |

51.0 (10.6) |

39.2 (4.0) |

31.7 (−0.2) |

29.1 (−1.6) |

37.6 (3.1) |

| Source: PRISM Climate Group[31] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Rincon Mountain Visitor Center, Saguaro National Park. Elev: 3048 ft (929 m) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 65.0 (18.3) |

67.7 (19.8) |

73.1 (22.8) |

80.8 (27.1) |

90.2 (32.3) |

99.1 (37.3) |

98.9 (37.2) |

96.3 (35.7) |

94.0 (34.4) |

84.3 (29.1) |

73.4 (23.0) |

64.6 (18.1) |

82.3 (27.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 51.3 (10.7) |

53.7 (12.1) |

58.3 (14.6) |

64.8 (18.2) |

73.8 (23.2) |

82.7 (28.2) |

85.3 (29.6) |

83.5 (28.6) |

80.0 (26.7) |

69.5 (20.8) |

58.7 (14.8) |

50.7 (10.4) |

67.8 (19.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 37.5 (3.1) |

39.6 (4.2) |

43.5 (6.4) |

48.8 (9.3) |

57.3 (14.1) |

66.2 (19.0) |

71.7 (22.1) |

70.6 (21.4) |

66.1 (18.9) |

54.8 (12.7) |

44.0 (6.7) |

36.8 (2.7) |

53.1 (11.7) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.15 (29) |

1.15 (29) |

1.15 (29) |

0.36 (9.1) |

0.24 (6.1) |

0.26 (6.6) |

2.57 (65) |

2.63 (67) |

1.37 (35) |

1.17 (30) |

0.75 (19) |

1.24 (31) |

14.04 (357) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 40.2 | 38.5 | 31.8 | 24.2 | 20.6 | 19.0 | 33.9 | 43.2 | 36.5 | 32.4 | 34.0 | 40.8 | 32.9 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 27.9 (−2.3) |

29.0 (−1.7) |

28.4 (−2.0) |

27.3 (−2.6) |

30.9 (−0.6) |

36.3 (2.4) |

53.7 (12.1) |

58.8 (14.9) |

51.0 (10.6) |

38.7 (3.7) |

30.4 (−0.9) |

27.7 (−2.4) |

36.7 (2.6) |

| Source: PRISM Climate Group[31] | |||||||||||||

Geology edit

Saguaro National Park's oldest rocks, the Pinal Schist, predate the formation of the contemporary Basin and Range Province, of which the park is a part, by about 1.7 billion years.[32] The schist is exposed in the Rincon Mountain District along a dry wash off Cactus Forest Loop Drive.[33] Other ancient rocks, 1.4-billion-year-old altered granites, form much of Tanque Verde Ridge[32] in the Rincon Mountain District.

Much later, about 600 million years ago, shallow seas covered the region around present-day Tucson; over time that led to deposition of sedimentary rocks—limestones, sandstones, and shales.[32] Limestone, which occurs in the park in several places, was mined here in the late 19th century to make mortar.[32] The future park land had six lime kilns, two in the Tucson Mountain District and four in the Rincon Mountain District. Three, all in the Rincon Mountain District, can be visited today—two along the Cactus Forest Trail and one along the Ruiz Trail.[34]

About 80 million years ago tectonic plate movements induced a period of mountain building, the Laramide orogeny, which lasted until about 50 million years ago in western North America. Explosive volcanic eruptions formed the Tucson Mountains about 70 million years ago,[35] and the roof of the volcano at their center collapsed to form a caldera 12 miles (19 km) across.[36][37] The caldera was eventually filled by debris flows, the intrusion of a granitic pluton, and lava flows, some as recent as 30 to 15 million years ago.[37] Volcanic rocks exposed in and near the Tucson Mountain District are remnants of these events.[35] Examples include large breccia exposed at Grants Pass and a granitic remnant of the magma chamber, which is visible from the Sus Picnic Area in the Tucson Mountain District.[38] Not all of the molten granite reached the surface of the Tucson Mountains; some cooled and crystallized far below.[35]

The Tucson Basin and nearby mountains—including the Tucson Mountains to the west, the Santa Catalinas to the north, and the Rincons to the east—are part of the Basin and Range Province extending from northern Mexico to southern Oregon in the United States.[35] The province, of relatively recent geologic origin, formed when plate movements stretched and thinned the Earth's crust in this part of western North America until the crust pulled apart along faults.[35] The Catalina Fault, a low-angle detachment fault, began to form about 30 million years ago about 6 to 8 miles (10 to 13 km) below the surface of the Tucson Mountains.[39] The rocks under the fault, the lower-plate rocks, were eventually displaced 16 to 22 miles (26 to 35 km) east-northeast relative to the rocks above the fault, then uplifted, domed, and eroded to form the Santa Catalina and Rincon mountains visible today.[37] Although the volcanic rocks seen on the surface of the Tucson Mountain District are not found in the Rincon Mountain District,[32] the crystallized granite (Catalina gneiss) from beneath the Tucson Mountains was eventually exposed on the Rincon Mountain District's surface.[37] The most common rock type in the Rincon Mountains, this banded gneiss is visible in the Rincon Mountain District at sites such as Javelina Rocks along the Cactus Forest Loop Drive.[40]

History edit

Early edit

The earliest known residents of the land in and around what later became Saguaro National Park were the Hohokam, who lived there in villages between AD 200 and 1450. Petroglyphs and bits of broken pottery are among Hohokam artifacts found in the park.[41] The Hohokam hunted deer and other animals, gathered cholla buds, prickly pears, palo verde pods, and saguaro fruit, and grew corn, beans, and squash. Subsequent indigenous cultures, the Sobaipuri of the Tucson Basin and the Tohono O'odham to the west, may be descendants of the Hohokam,[42] though the evidence is inconclusive.[43]

Spanish explorers first entered Arizona in 1539–40.[42] Non-native settlement of the region near the park did not occur until 1692 with the founding of San Xavier Mission along the Santa Cruz River,[42][44] which flowed through Tucson.[22] In 1775, the Spaniards built Presidio San Agustín del Tucsón, a military fort in what was then part of New Spain,[45] in part to protect against raids by Apaches.[42]

The lands that eventually would become Saguaro National Park remained relatively free of development until the mid-19th century, after Arizona had become part of the United States. After passage of the Homestead Act of 1862, the arrival of the railroad in 1880, and the end of the Apache Wars in 1886, homesteaders and ranchers established themselves in the Tucson and Rincon Mountains, and miners sought silver, copper, and other valuable ores and minerals.[42] Mining in the park continued intermittently through 1942,[46] while ranching on private in-holdings within the park continued until the mid-1970s.[47]

The defunct Loma Verde Mine, which is still visible in the Rincon Mountain District,[42] produced a small amount of copper and gold between 1897 and 1907.[48] Mining of igneous rock at 149 sites in the Tucson Mountain District sometimes produced ores of modest value in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[49] The most successful, the Copper King Mine (later renamed the Mile Wide Mine), yielded 34,000 tons of copper, gold, lead, zinc, and molybdenum ores, mostly during the war years of 1917, 1918, and 1941; it closed permanently in 1942 when it became unprofitable.[46]

Ranchers grazed thousands of cattle on public land that would later become part of the park, and homesteaders farmed and ranched at the base of the Rincons,[42] filing homestead applications from the 1890s through 1930.[50] The remains of the former Freeman Homestead, established in 1929, lie along a nature trail in the Rincon Mountain District. The homestead is on the Arizona State Register of Historic Places.[50] Manning Cabin, built in 1905 as a summer retreat for Levi Manning, a wealthy businessman and one-term mayor of Tucson, is part of the infrastructure at Manning Camp near Mica Mountain.[42][51] Modified and restored after falling into disrepair, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1975.[51] Cultural resources in the park include more than 450 archeological sites and more than 60 historic structures.[52]

After 1920 edit

In 1920 members of the Natural History Society of the University of Arizona expressed interest in establishing a protected area for saguaro, a cactus species familiar to watchers of silent-movie Westerns. In 1928 Homer L. Shantz, a plant scientist and the university's president, joined the efforts to create a saguaro sanctuary,[53] but issues related to funding and management delayed the creation of a park. In 1933 Frank Harris Hitchcock, publisher of the Tucson Citizen and a former United States Postmaster General who was influential in the Republican Party, persuaded U.S. President Herbert Hoover to create Saguaro National Monument.[54] Hoover used his power under the Antiquities Act of 1906 to create the monument by proclamation on March 1, 1933.[55][56] Later that year President Franklin D. Roosevelt transferred management of the monument, east of Tucson in the Rincon Mountains, to the National Park Service.[53] Between 1936 and 1939, during the Roosevelt administration, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) built the monument's Cactus Forest Loop Drive and related infrastructure.[57] The monument's visitor center opened in the 1950s.[53]

In 1961 President John F. Kennedy—encouraged by Stewart Udall, an Arizonan who was then Secretary of the Interior—added 16,000 acres (6,500 ha) of cactus lands in the Tucson Mountains to the monument.[53] This western district of the monument was carved from Tucson Mountain Park, managed by Pima County. In the 1920s, the Tucson Game Protective Association had persuaded the Department of the Interior to withdraw about 30,000 acres (12,000 ha) in the Tucson Mountains from homesteading and mining and to set it aside as a park and game refuge. Land leased by the county in this set-aside became the Tucson Mountain Recreation Area in 1932. Between 1933 and 1941 CCC workers built structures at eight picnic areas in the county-park portion of the set-aside, five of which later became part of the Tucson Mountain District of the national monument. Their other projects involved road- and trail-building, landscaping, erosion control, and enhancing water supplies for wildlife. Kennedy's 1961 proclamation created the Tucson Mountain District from the northern part of the county park and renamed the original monument lands east of Tucson the Rincon Mountain District.[13] Expansions in 1976 and 1994 brought the total Tucson Mountain District area to 24,818 acres (10,043 ha). In 1994 Congress elevated the combined Tucson Mountain District and Rincon Mountain District to National Park status.[53] The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 added 1,232 acres (4.99 km2) to the park.[58]

Biology edit

Plants and fungi edit

According to the A. W. Kuchler U.S. Potential natural vegetation Types, Saguaro National Park encompasses four classifications; a Parkinsonia/Cactus (43) vegetation type with a Deserts and xeric shrublands (8) vegetation form, a Creosote bush scrub/Ragweed (42) vegetation type with a Deserts and xeric shrublands (8) vegetation form, a Bouteloua/Pleuraphis mutica Steppe (58) vegetation type with a Desert Steppe (14) vegetation form, and an Oak/Juniper Woodland (31) vegetation type with a Great Basin montane forests/Southwest Forest (4) vegetation form.[59]

Plant communities within the park vary with elevation. The Tucson Mountain District has two distinct communities, desert scrub[4]—such as fourwing saltbush[60] and brittlebrush[61]—at the lowest elevations, and desert grassland a little higher. The Rincon Mountain District includes these two communities as well as four more at higher elevations, oak woodland, pine–oak woodland, pine forest and, high in the Rincons, mixed conifer forest[4]—Douglas-fir, Ponderosa pine, white fir, Gambel oak, and many other trees, shrubs, and understory plants.[62] During annual inventories in 2011 and 2013, hundreds of scientists and thousands of volunteers identified 389 species of vascular plants, 25 of non-vascular plants, and 197 species of fungi in Saguaro National Park.[63]

Saguaros, which flourish in both districts of the park, grow at an exceptionally slow rate. The first arm of a saguaro typically appears when the cactus is between 50 and 70 years old though it may be closer to 100 years in places where precipitation is very low. Saguaros may live as long as 200 years and are considered mature at about age 125.[64] A mature saguaro may grow up to 60 feet (18 m) tall and weigh up to 4,800 pounds (2,200 kg) when fully hydrated.[5] The total number of saguaros in the park is estimated at 1.8 million,[65] and 24 other species of cactus are abundant. The most common of these are the fishhook barrel, staghorn cholla, pinkflower hedgehog, Engelman's prickly pear, teddybear cholla, and jumping cholla.[66]

Invasive plants include fountain grass, tamarisk, Malta starthistle, and many others, but by far the most severe threat to the native ecosystem is buffelgrass.[67] This drought-tolerant plant, native to parts of Africa and Asia, was imported to the United States in the 1930s and planted near Tucson and elsewhere to create cattle forage and to control erosion. First detected in the park in 1989, it has dispersed widely in both districts. Competing with other plants for sustenance, buffelgrass fills the empty spaces normally found between native desert plants and creates a significant fire hazard. The noxious weed, considered impossible to eliminate, is managed in some areas of the park and in Tucson residential zones by hand-pulling and, during periods of wet weather, application of glyphosate-based herbicides.[68]

Animals edit

An inventory of medium and large mammals in the park confirmed the presence of 30 species in Saguaro National Park between 1999 and 2008. Of these, 21 were found in the Tucson Mountain District and 29 in the Rincon Mountain District.[69] A partial list of the park's mammals includes cougars, coyotes, bobcats, white-tailed deer, mule deer, javelinas, gray foxes, black-tailed jackrabbits, desert cottontails, ring-tailed cats, white-nosed coatis, ground squirrels, and packrats.[70] One endangered mammal, the lesser long-nosed bat, lives part of the year in the park and part of the year in Mexico.[71]

The wide range of habitats in the park supports a diverse population of birds, including some that are uncommon elsewhere in the United States, such as the vermilion flycatcher and the whiskered screech owl.[72] Among the park's 107 bird species[63] are great horned owls, cactus wrens, ravens, kestrels, turkey vultures, roadrunners, woodpeckers, hawks, quails, hummingbirds,[73] and one threatened species, the Mexican spotted owl.[74]

The park's 36 reptile species[63] include desert tortoises, diamondback rattlesnakes (one of the more commonly seen snakes), coral snakes, Gila monsters, short-horned lizards, spiny lizards, and zebra-tailed lizards.[75] Despite the aridity, three amphibian species inhabit the park:[63] the canyon tree frog, the lowland leopard frog, and Couch's spadefoot, which lives in burrows, emerging to breed during summer rains.[76] Forest fires, which create erosion-prone burned areas, have destroyed many of the leopard frog's breeding pools, which fill with sediment. The Arizona Game and Fish Department lists the lowland leopard frog as a species of special concern.[77]

Urban sprawl, air and water pollution, noise, light pollution, and a range of habitat restricted by human infrastructure put stress on the park's mammals and other animals, but the most serious immediate threat to them is roadkill. About 50,000 vertebrates a year die on the park's roads when they are hit by a vehicle. The Rincon Mountain District has few roads, but Picture Rocks Road, an east–west commuter highway crossing the Tucson Mountain District, is highly dangerous to wildlife. Attempts in 2002 to convert it to a hiking trail failed after the proposal met with stiff public resistance.[78]

Sky Islands edit

The Rincons and the nearby Santa Catalinas (but not the shorter Tucson Mountains) are among about 40 mountain ranges known as the Madrean Sky Islands that are of special interest to biologists.[79] These ranges resemble a series of stepping stones between the southern end of the Rocky Mountains—specifically the Mogollon Rim of the Colorado Plateau—in the United States and the Sierra Madre Occidental in Mexico. The continental "islands" are separated from one another by "seas" of lower-elevation valleys that impede but do not completely block species migration from one sky island to another. Ecologist Peter Warshall lists several characteristics that make the Madrean complex unique among Earth's 20 or so sky-island complexes. Among these are its north–south orientation across eight degrees of latitude spanning zones from the temperate to the subtropical, the highly varied nature of its geologic origin and of its soils, the moderate to high relief of its terrain, and its safe distance from the mass extinctions related to the northern glaciers of the most recent Ice Age. Influenced by these and other conditions, the Madrean Sky Islands support unusual biodiversity.[80]

Recreation edit

The park is generally open to hikers all day every day except Christmas; the Tucson Mountain District is open to vehicle traffic from sunrise to sunset and the Rincon Mountain District from 7 a.m. to sunset. Both districts have visitor centers.[81] More than 165 miles (266 km) of hiking trails wind through the park,[82] where perils may include extreme heat, dehydration, flash floods, cactus spines, snakes, cougars, bears, and Africanized bees.[83] The Rincon Mountain District is open to wilderness camping, which requires a permit,[18][84] but no overnight camping is permitted in the Tucson Mountain District.[85]

Tucson Mountain District edit

The Tucson Mountain District has 12 miles (19 km) of paved roads and 8.5 miles (13.7 km) of unpaved roads,[86] including the 5-mile (8 km) Bajada Loop Drive.[19] Bicycling is allowed only on paved roads, as well as Bajada Loop Drive, Golden Gate Road, and the Belmont multi-use trail.[87][88] Horses and other livestock are allowed on some of the trails.[87]

Hohokam petroglyphs etched into large stones are easily accessible in the Tucson Mountain District. The Signal Hill Trail, which begins at the Signal Hill Picnic Area along the Bajada Loop Drive, leads to an area with dozens of examples of the 800-year-old rock art.[89]

Among the notable artificial structures in the Tucson Mountain District are ramadas, picnic tables, and restrooms built by the Civilian Conservation Corps between 1933 and 1941. Designed to conform to their natural surrounds, the rustic buildings consist mainly of quarried stone and other materials native to the area.[90]

The Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum lies just south of the Tucson Mountain District along North Kinney Road in Tucson Mountain County Park. The non-profit organization, operating on 98 acres (40 ha) rented from Pima County, combines aspects of a botanical garden, zoo, and natural history museum featuring the plants and animals native to the region.[91]

Rincon Mountain District edit

The Rincon Mountain District features the 8.3-mile (13.4 km) Cactus Forest Loop Drive, which provides access to some of the trails.[57][87] Angling across the Rincon Mountain District from southwest to northeast is a segment of the Arizona Trail.[92] The 800-mile (1,300 km) trail crosses Arizona from its border with Mexico on the south to its border with Utah on the north. In 2009, Congress named it a National Scenic Trail.[93]

Horseback riding is allowed on some of the trails.[87] Livestock—defined by the NPS as horses, mules, or burros—must carry their own food and are not allowed to graze in the park.[85] Bicycling is allowed on the Cactus Forest Loop Drive and two park trails.[87][88]

Manning Camp Campground is the main staging area for firefighters, trail-maintenance crews, and scientists working in the Rincon Mountain District. Their supplies are brought in by pack mules that are kept in corrals at the site.[18] Runoff from a nearby spring, the largest in the Rincons, provides water for the livestock.[25]

On a 40-acre (16 ha) plot adjacent to the Rincon Mountain District along Broadway, the Desert Research Learning Center (DRLC) supports scientific and educational projects related to a network of Sonoran Desert parks, including Saguaro National Park. The DRLC grounds, which include desert plants, an artificial tinaja, and a rainwater collection system, are open to the public.[94] The Sonoran Desert Inventory and Monitoring Network of which the DRLC is part, covers 10 national monuments or parks in Arizona and one in New Mexico.[95]

See also edit

References edit

- ^ a b Land Resources Division (December 31, 2016). "National Park Service Listing of Acreage (summary)" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved June 11, 2017.

- ^ "S.316 – Saguaro National Park Establishment Act of 1994". Library of Congress. 1994. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ^ "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved October 16, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "Nature and Science". National Park Service. January 11, 2017. Archived from the original on June 20, 2017. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- ^ a b "Plant Fact Sheet: Saguaro Cactus". Arizona–Sonora Desert Museum. 2008. Archived from the original on October 9, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ a b Barnes 1988, p. 364.

- ^ Ring, Bob (August 9, 2012). "Get to Know Mountains Surrounding Old Pueblo". Arizona Daily Star. p. G009 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Barnes 1988, p. 455.

- ^ Dilsaver 2015, p. 33.

- ^ Bennett, Peter S.; Kunzmann, Michael R. (1992). "The Applicability of Generalized Fire Prescriptions to Burning of Madrean Evergreen Forest and Woodland". Journal of the ArizonaNevada Academy of Science. 24–25: 79–84. JSTOR 40021298.

- ^ Annerino, John (July 3, 1994). "The Wild Country of Mexico". Arizona Republic. p. 34. Retrieved October 9, 2017 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Rand McNally Road Atlas (Map). Chicago: Rand McNally. 2016. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-528-01313-3.

- ^ a b "The Creation and Evolution of the Tucson Mountain District of Saguaro National Park" (PDF). National Park Service. 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 20, 2017. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ^ Calculated by subtracting the Tucson Mountain District approximation from the total acreage.

- ^ "Saguaro Wilderness". Wilderness Connect. U.S. Government and The University of Montana. Archived from the original on September 5, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017. The map at this site, when zoomed out sufficiently, outlines the wilderness areas in both districts.

- ^ a b c d Arizona Road & Recreation Atlas (Map) (7th ed.). Benchmark Maps. 2012. pp. 102–03. ISBN 978-0-929591-97-1.

- ^ "Rincon Mountain Wilderness". Wilderness Connect. U.S. Government and The University of Montana. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ a b c "The Saguaro Wilderness Area" (PDF). Retrieved March 2, 2017.

- ^ a b Enjoying Saguaro National Park (brochure). National Park Service. 2011.

- ^ "Mica Mountain". Peakbagger. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ^ National Park Service 2016, p. 4.

- ^ a b Regan, Margaret (May 3, 2001). "A River Ran Through It". Tucson Weekly. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ National Park Service 2016, p. 12.

- ^ National Park Service 2016, pp. 4, 8.

- ^ a b National Park Service 2016, p. 9.

- ^ "USDA Interactive Plant Hardiness Map". United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ Jordan, Emmett (February 9, 1986). "Giant Saguaros Have Dominion of Savage Land". Albuquerque Journal. p. 51.

- ^ National Park Service 2016, p. 2.

- ^ "Recent Climate Change Exposure of Saguaro National Park" (PDF). National Park Service. July 28, 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 20, 2017. Retrieved June 29, 2017.

- ^ "Monitoring the Effects of Climate Change". National Park Service. December 30, 2016. Archived from the original on January 31, 2017. Retrieved June 29, 2017.

- ^ a b "PRISM Climate Group, Oregon State University". www.prism.oregonstate.edu. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "Geology of the Rincon Mountains" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 20, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Bezy 2005, p. 12.

- ^ "Lime Kilns" (PDF). National Park Service. January 2015. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Bezy 2005, p. 6.

- ^ "Saguaro National Park". Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d Bezy 2005, p. 20.

- ^ Bezy 2005, pp. 24, 29.

- ^ Bezy 2005, p. 9.

- ^ Bezy 2005, p. 18.

- ^ "Archeological Site Condition Assessment" (PDF). National Park Service. January 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 15, 2017. Retrieved July 8, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Those Who Came Before" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 20, 2017. Retrieved February 26, 2017.

- ^ Bayman, James M. (September 2001). "The Hohokam of Southwest North America". Journal of World Prehistory. 15 (3). New York: Springer: 292–93. doi:10.1023/a:1013124421690. S2CID 162570620.

- ^ "A Brief History of Mission San Xavier del Bac". Mission San Xavier del Bac. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ "El Presidio Historic District". National Park Service. Archived from the original on June 12, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ a b Ascarza, William (August 30, 2015). "Short-lived Mine Produced Ore in Tucson Mountains". Arizona Daily Star. Retrieved November 9, 2017 – via Tucson.com.

- ^ Kenney, Douglas S.; Cannon, Doug (2004). "Saguaro National Park Case Study" (PDF). Books, Reports, and Studies. University of Colorado Boulder, Natural Resources Law Center: 7. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

- ^ Clemenson, Berle A. (1987). "Chapter 3C: In Pursuit of Valuable Ore: The Rincon Mining District". Cattle, Copper, and Cactus: The History of Saguaro National Monument. National Park Service. Archived from the original on August 22, 2017. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "History of Mining in Saguaro National Park, West" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

- ^ a b "Freeman and Other Homesteads" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 27, 2017. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ a b "Levi Manning and Manning Cabin: Past and Present". National Park Service. March 9, 2016. Archived from the original on August 22, 2017. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Cultural Resource Management Program" (PDF). National Park Service. January 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 22, 2017. Retrieved July 10, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "SNP History". National Park Service. April 11, 2015. Archived from the original on June 20, 2017. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- ^ Leighton, David (February 14, 2014). "Street Smarts: General Hitchcock Highway Remembers a Man Whose Influence Went from D.C. to Tucson and Back". Arizona Daily Star. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- ^ "Standing Tall at 75 – Saguaro National Park Celebrates Its Diamond Anniversary" (PDF). National Park Service. February 21, 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ "Monuments Protected Under the Antiquities Act". National Parks Conservation Association. January 13, 2017. Archived from the original on October 4, 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- ^ a b "Cactus Forest Drive" (PDF). National Park Service. January 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- ^ "SAGUARO NATIONAL PARK Proposed Boundary Adjustment. MAP NUMBER: 151/80,045G" (PDF).

- ^ "U.S. Potential Natural Vegetation, Original Kuchler Types, v2.0 (Spatially Adjusted to Correct Geometric Distortions)". Data Basin. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ Sonoran_Desert_Network 2011, p. 19.

- ^ Sonoran_Desert_Network 2011, p. 29.

- ^ Baisan, C. H.; Swetnam, T. W. (1990). "Fire History on a Desert Mountain Range: Rincon Mountain Wilderness, Arizona, U.S.A." (PDF). Canadian Journal of Forest Research. 20 (10): 1559–69. doi:10.1139/x90-208. Retrieved October 29, 2017 – via University of Arizona Laboratory of Tree Ring Research. To view the PDF, click on the BaisanSwetnam item in the index.

- ^ a b c d "BioBlitz Count Update from the Saguaro NP BioBlitz 2011" (PDF). National Park Service. October 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 20, 2017. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ^ "How Saguaros Grow". National Park Service. February 24, 2015. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ "The Saguaro Cactus" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- ^ "Cacti / Desert Succulents". National Park Service. February 24, 2015. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- ^ "Invasive Plants". National Park Service. September 6, 2016. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved June 17, 2017.

- ^ "Buffelgrass". National Park Service. May 19, 2015. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved June 17, 2017.

- ^ Swann, Don E.; Powell, Brian. "Inventory of Medium and Large Mammals at Saguaro National Park" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 20, 2017. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ^ "Mammals of Saguaro National Park". National Park Service. February 15, 2017. Archived from the original on June 20, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ "Lesser Long-Nosed Bats" (PDF). National Park Service. December 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 20, 2017. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- ^ "Birds". National Park Service. September 9, 2016. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

- ^ "Aves (Birds) of Saguaro National Park". National Park Service. February 15, 2017. Archived from the original on June 20, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ "Mexican Spotted Owl" (PDF). National Park Service. January 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 20, 2017. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- ^ "Reptiles of Saguaro National Park". National Park Service. February 15, 2017. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ "Amphibians". National Park Service. February 25, 2015. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved June 17, 2017.

- ^ Parker, John T. C. (January 2006). "Effects of Post-Wildfire Sedimentation on Leopard Frog Habitat in Saguaro National Park" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 20, 2017. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- ^ "Connecting Saguaro National Park to Its Surrounding Landscapes" (PDF). National Park Service. January 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 20, 2017. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

- ^ Skroch, Matt (21 January 2008). "Sky Islands of North America". Terrain.org. Winter/Spring 2008 (21). Terrain Publishing. ISSN 1932-9474. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- ^ Warshall, Peter (July 1995). "The Madrean Sky Island Archipelago: A Planetary Overview". In DeBano, Leonard F. (ed.). Biodiversity and the Management of the Madrean Archipelago: The Sky Islands. U.S. Forest Service. pp. 6–18. doi:10.2737/RM-GTR-264. File is accessed by clicking on "View PDF".

- ^ "Operating Hours". National Park Service. May 28, 2015. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ^ "Hiking at Saguaro National Park". National Park Service. June 14, 2015. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ "Safety". National Park Service. June 4, 2016. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ "Park Regulations". National Park Service. February 26, 2017. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ a b "Park News" (PDF). Saguaro Sentinel. National Park Service. December 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2017. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ^ "General Information" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 20, 2017. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "Getting Around". National Park Service. March 23, 2017. Archived from the original on June 20, 2017. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ^ a b "Bicycling at Saguaro National Park". National Park Service. February 23, 2015. Archived from the original on September 29, 2017. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ^ "Petroglyphs". National Park Service. April 10, 2015. Archived from the original on June 20, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ "NPS Rustic Style Architecture" (PDF). National Park Service. February 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

- ^ "Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum Overview and History". Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum. 2017. Archived from the original on July 3, 2017. Retrieved October 9, 2017.

- ^ "Rincon Mountain District (East)" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 20, 2017. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ^ "Arizona National Scenic Trail". National Forest Service. Archived from the original on October 17, 2017. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ^ "The Desert Research Learning Center". National Park Service. December 30, 2016. Archived from the original on October 12, 2017. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

- ^ "Sonoran Desert Network". National Park Service. May 23, 2017. Archived from the original on June 10, 2017. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

Works cited edit

- Barnes, Will C. (1988). Arizona Place Names. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-1074-0.

- Bezy, John (2005). A Guide to the Geology of Saguaro National Park. Tucson: Arizona Geological Society. ISBN 978-1-892001-22-1.

- Dilsaver, Lary M. (March 2015). Joshua Tree National Park: A History of Preserving the Desert (PDF). National Park Service. OCLC 912308073. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 9, 2017. Retrieved July 9, 2017.

- National Park Service (2016). Explore the Waters of Saguaro National Park: A Story Map (Map). National Park Service. Retrieved May 17, 2017 – via Esri.

- Sonoran Desert Network (2011). Buckley, Steve (ed.). Common Plants of Saguaro National Park (PDF). National Park Service.