Carya tomentosa, commonly known as mockernut hickory, mockernut, white hickory, whiteheart hickory, hognut, bullnut, is a species of tree in the walnut family Juglandaceae. The most abundant of the hickories, and common in the eastern half of the United States, it is long lived, sometimes reaching the age of 500 years. A straight-growing hickory, a high percentage of its wood is used for products where strength, hardness, and flexibility are needed. The wood makes excellent fuel wood, as well. The leaves turn yellow in Autumn.

| Mockernut hickory | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Fagales |

| Family: | Juglandaceae |

| Genus: | Carya |

| Section: | Carya sect. Carya |

| Species: | C. tomentosa

|

| Binomial name | |

| Carya tomentosa | |

| |

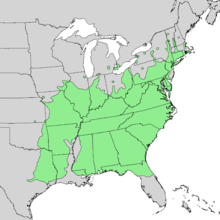

| Natural range of Carya tomentosa | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

Carya alba L. | |

The species' name comes from the Latin word tomentum, meaning "stuffing",[3] referring to the underside of the leaves, which are covered with dense, short hairs, which help identify the species. Also called the white hickory due to the light color of the wood, the common name mockernut likely refers to the would-be nut eater, who would struggle to crack the thick shell only to find a small, unrewarding nut inside.[4]

Habitat

editNative range

editMockernut hickory, a true hickory, grows from Massachusetts and New York west to southern Ontario, and northern Illinois; then to southeastern Iowa, Missouri, and eastern Kansas, south to eastern Texas and east to northern Florida. This species is not present in Michigan, New Hampshire and Vermont as previously mapped by Little.[5] Mockernut hickory is most abundant southward through Virginia, North Carolina, and Florida, where it is the most common of the hickories. It is also abundant in the lower Mississippi Valley and grows largest in the lower Ohio River Basin and in Missouri and Arkansas.[6][7]

Climate

editThe climate where mockernut hickory grows is usually humid. Within its range, the mean annual precipitation measures from 890 mm (35 in) in the north to 2,030 mm (80 in) in the south. During the growing season (April through September), annual precipitation varies from 510 to 890 mm (20 to 35 in). About 200 cm (79 in) of annual snowfall is common in the northern part of the range, but snow is rare in the southern portion.

Annual temperatures range from 10 to 21 °C (50 to 70 °F). Monthly average temperatures range from 21 to 27 °C (70 to 81 °F) in July and from −7 to 16 °C (19 to 61 °F) in January. Temperature extremes are well above 38 °C (100 °F) and below −18 °C (0 °F). The growing season is about 160 days in the northern part of the range and up to 320 days in the southern part of the range.[8][9]

Soils and topography

editIn the north, mockernut hickory is found on drier soils of ridges and hillsides and less frequently on moist woodlands and alluvial bottoms.[7] The species grows and develops best on deep, fertile soils.[6][10] In the Cumberland Mountains and hills of southern Indiana, it grows on dry sites such as south and west slopes or dry ridges. In Alabama and Mississippi, it grows on sandy soils with shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata) and loblolly pine (P taeda). However, most of the merchantable mockernut grows on moderately fertile upland soils.[7]

Mockernut hickory grows primarily on ultisols occurring on an estimated 65% of its range, including much of the southern to northeastern United States.[11] These soils are low in nutrients and usually moist, but during the warm season, they are dry part of the time. Along the mid-Atlantic and in the southern and western range, mockernut hickory grows on a variety of soils on slopes of 25% or less, including combinations of fine to coarse loams, clays, and well-drained quartz sands. On slopes steeper than 25%, mockernut often grows on coarse loams.

Mockernut grows on inceptisols in an estimated 15% of its range. These clayey soils are moderate to high in nutrients and are primarily in the Appalachians on gentle to moderate slopes, where water is available to plants during the growing season. In the northern Appalachians on slopes of 25% or less, mockernut hickory grows on poorly drained loams with a fragipan. In the central and southern Appalachians on slopes 25% or less, mockernut hickory grows on fine loams. On steeper slopes, it grows on coarse loams.[11]

In the northwestern part of the range, mockernut grows on mollisols. These soils have a deep, fertile surface horizon greater than 25 cm (9.8 in) thick. Mollisols characteristically form under grass in climates with moderate to high seasonal precipitation.

Mockernut grows on a variety of soils including wet, fine loams, sandy textured soils that often have been burned, plowed, and pastured. Alfisols are also present in these areas and contain a medium to high supply of nutrients. Water is available to plants more than half the year or more than three consecutive months during the growing season. On slopes of 25% or less, mockernut grows on wet to moist, fine loam soils with a high carbonate content.[11]

Associated forest cover

editMockernut hickory is associated with the eastern oak-hickory forest and the beech-maple forest. The species does not exist in sufficient numbers to be included as a title species in the Society of American Foresters forest cover types. Nevertheless, it is identified as an associated species in eight cover types. Three of the upland oak types and the bottom land type are subclimax to climax.

In the central forest upland oak types, mockernut is commonly associated with:

- pignut hickory (Carya glabra)

- shagbark hickory (C. ovata)

- bitternut hickory (C. cordiformis)

- black oak (Quercus velutina)

- scarlet oak (Q. coccinea)

- post oak (Q. stellata)

- bur oak (Q. macrocarpa)

- blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica)

- yellow-poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera)

- maples (Acer spp.)

- white ash (Fraxinus americana)

- eastern white pine (Pinus strobus)

- eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis)

Common understory vegetation includes:

- flowering dogwood (Cornus florida)

- sumac (Rhus spp.)

- sassafras (Sassafras albidum)

- sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum)

- downy serviceberry (Amelanchier spp.)

- redbud (Cercis canadensis)

- eastern hophornbeam (Ostrya virginiana)

- American hornbeam (Carpinus caroliniana)

Mockernut is also associated with:

- wild grapes (Vitis spp.)

- rosebay rhododendron (Rhododendron maximum)

- mountain-laurel (Kalmia latifolia)

- greenbriers (Smilax spp.)

- blueberries (Vaccinium spp.)

- witch-hazel (Hamamelis virginiana)

- spicebush (Lindera benzoin)

- New Jersey tea (Ceanothus americanus)

- wild hydrangea (Hydrangea arborescens)

- tick-trefoil (Desmodium spp.)

- bluestem (Andropogon spp.)

- poverty oatgrass (Danthonia spicata)

- sedges (Carex spp.)

- pussytoes (Antennaria spp.)

- goldenrod (Solidago spp.)

- asters (Aster or other genera, depending on the classification).

In the southern forest, mockernut grows with:

- shortleaf pine

- loblolly pine

- pignut hickory

- gums

- oaks

- sourwood

- winged elm (Ulmus alata)

- flowering dogwood

- redbud

- sourwood

- persimmon (Diospyros uirginiana)

- eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana)

- sumacs

- hawthorns (Crataegus spp.)

- blueberries

- honeysuckle (Lonicera spp.)

- mountain-laurel

- viburnums

- greenbriers

- grapes

In the loblolly pine-hardwood type in the southern forest, mockernut commonly grows in the upland and drier sites with:

- white oak (Quercus alba)

- post oak

- northern red oak (Q. rubra)

- southern red oak (Q. falcata)

- scarlet oak

- shagbark and pignut hickories

- blackgum

- flowering dogwood

- hawthorn

- sourwood

- greenbrier

- grape

- honeysuckle

- blueberry

In the southern bottom lands, mockernut occurs in the swamp chestnut oak-cherrybark oak type along with:

- green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica)

- white ash

- shagbark

- shellbark hickory (Carya laciniosa)

- bitternut hickories

- white oak

- delta post oak (Quercus stellata var. paludosa)

- Shumard oak (Q. shumardii)

- blackgum.

Understory trees include:

- American pawpaw (Asimina triloba)

- flowering dogwood

- painted buckeye (Aesculus sylvatica)

- American hornbeam

- devils-walking stick (Aralia spinosa)

- redbud

- American holly (Ilex opaca)

- Dwarf palmetto (Sabal minor)

- Coastal plain willow (Salix caroliniana)

Life history

editReproduction and early growth

editFlowering and fruiting

editMockernut hickory is monoecious - male and female flowers are produced on the same tree. Mockernut male flowers are catkins about 10 to 13 cm (3.9 to 5.1 in) long and may be produced on branches from axils of leaves of the previous season or from the inner scales of the terminal buds at the base of the current growth. The female flowers appear in short spikes on peduncles terminating in shoots of the current year. Flowers bloom in the spring from April to May, depending on latitude and weather. Usually the male flowers emerge before the female flowers. Hickories produce very large amounts of pollen that is dispersed by the wind.

Fruits are solitary or paired and globose, ripening in September and October, and are about 2.5 to 9.0 cm (0.98 to 3.54 in) long with a short necklike base. The fruit has a thick, four-ribbed husk 3 to 4 mm (0.12 to 0.16 in) thick that usually splits from the middle to the base. The nut is distinctly four-angled with a reddish-brown, very hard shell 5 to 6 mm (0.20 to 0.24 in) thick containing a small edible kernel.

Seed production and dissemination

editThe seed is dispersed from September through December. Mockernut hickory requires a minimum of 25 years to reach commercial seed-bearing age. Optimum seed production occurs from 40 to 125 years, and the maximum age listed for commercial seed production is 200 years.

Good seed crops occur every two to three years with light seed crops in intervening years. Around 50 to 75% of fresh seed will germinate. Fourteen mockernut hickory trees in southeastern Ohio produced an average annual crop of 6,285 nuts for 6 years; about 39% were sound, 48% aborted, and 13% had insect damage. Hickory shuckworm (Laspeyresia caryana) is probably a major factor in reducing germination.

Mockernut hickory produces one of the heaviest seeds of the hickory species; cleaned seeds range from 70 to 250 seeds/kg (32 to 113/lb). Seed is disseminated mainly by gravity and wildlife, particularly squirrels. Birds also help disperse seed. Wildlife such as squirrels and chipmunks often bury the seed at some distance from the seed-bearing tree.

Seedling development

editHickory seeds show embryo dormancy that can be overcome by stratification in a moist medium at 1 to 4 °C (34 to 39 °F) for 30 to 150 days. When stored for a year or more, seed may require stratification for only 30 to 60 days. Hickory nuts seldom remain viable in the ground for more than I year. Hickory species normally require a moderately moist seedbed for satisfactory seed germination, and mockernut hickory seems to reproduce best in moist duff. Germination is hypogeal.

Mockernut seedlings are not fast-growing. The height growth of mockernut seedlings observed in the Ohio Valley in the open or under light shade on red clay soil was:

| Age | Height | |

|---|---|---|

| (yr) | (cm) | (in) |

| 1 | 8 | 3.0 |

| 2 | 12 | 4.7 |

| 3 | 20 | 8.0 |

| 4 | 32 | 12.5 |

| 5 | 51 | 20.0 |

| 6 | 71 | 28.0 |

Vegetative reproduction

editTrue hickories sprout prolifically from stumps after cutting and fire. As the stumps increase in size, the number of stumps that produce sprouts decreases; age is probably directly correlated to stump size and sprouting. Coppice management is a possibility with true hickories. True hickories are difficult to reproduce from cuttings. Madden discussed the techniques for selecting, packing, and storing hickory propagation wood. Reed indicated that the most tested hickory species for root stock for pecan hickory grafts were mockernut and water hickory (Carya aquatica).

However, mockernut root stock grew slowly and reduced the growth of pecan tops. Also, this graft seldom produced a tree that bore well or yielded large nuts.

Sapling and pole stages to maturity

editGrowth and yield

editMockernut hickory is a large, true hickory with a dense crown. This species occasionally grows to about 30 m (98 ft) tall and 91 cm (36 in) in diameter at breast height (dbh), but heights and diameters usually range from about 15 and 46 to 61 cm (5.9 and 18.1 to 24.0 in), respectively.

The relation of height to age is:

| Height | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Cumberland Mountains | Mississippi Valley | ||

| (yr) | (m) | (ft) | (m) | (ft) |

| 10 | 1.2 | 4 | 2.7 | 9 |

| 20 | 5.2 | 17 | 5.5 | 18 |

| 30 | 7.9 | 26 | 7.6 | 25 |

| 40 | 10.1 | 33 | 9.1 | 30 |

| 60 | 13.7 | 45 | 12.2 | 40 |

| 80 | 16.8 | 55 | 14.9 | 49 |

| 100 | 20.1 | 66 | 17.4 | 57 |

| 120 | 23.2 | 76 | 19.8 | 65 |

| 160 | 28.7 | 94 | 24.4 | 80 |

| 200 | 33.2 | 109 | 29.0 | 95 |

The current annual growth of mockernut hickory on dry sites is estimated at 1.0 m3/ha (15 ft3/acre). In fully stocked stands on moderately fertile soil2.1 m3 /ha (30 ft3 /acre) is estimated, though annual growth rates of 3.1 m3/ha (44 ft3/acre) were reported in Ohio (26). Greenwood and bark weights for commercial-size mockernut trees from mixed hardwoods in Georgia are available for total tree and saw-log stems to a 4-inch top for trees 5 to 22 inches d.b.h..

Available growth data and other research information are summarized for hickory species, not for individual species. Trimble compared growth rates of various Appalachian hardwoods including a hickory species category dominant-codominant hickory trees 38 to 51 cm (15 to 20 in) in dbh on good oak sites grew slowly compared to northern red oak, yellow-poplar, black cherry (Prunus serotina), and sugar maple (Acer saccharum). Hickories were in the white oak, sweet birch (Betula lenta), and American beech (Fagus grandifolia) growth-rate category. Dominant-codominant hickory trees grew about 3 mm (0.12 in) dbh per year compared to 5 mm (0.20 in) for the moderate-growth species (black cherry) and 6 mm (0.24 in) for the faster-growing species (yellow-poplar and red oak). Equations are available for predicting merchantable gross volumes from hickory stump diameters in Ohio. Also, procedures are described for predicting diameters and heights and for developing volume tables to any merchantable top diameter for hickory species in southern Illinois and West Virginia. Generally, epicormic branching is not a problem with hickory species, but a few branches do occur.

Rooting habit

editTrue hickories such as mockernut develop a long taproot with few laterals. Early root growth is primarily into the taproot, which typically reaches a depth of 30 to 91 cm (12 to 36 in) during the first year. Small laterals originate along the taproot, but many die back during the fall. During the second year, the taproot may reach a depth of 122 cm (48 in), and the laterals grow rapidly. After 5 years, the root system attains its maximum depth, and the horizontal spread of the roots is about double that of the crown. By age 10, the height is four times the depth of the taproot.

Reaction to competition

editAt certain times during its life, mockernut hickory may be variously classified as tolerant to intolerant. Overall it is classified as intolerant of shade. It recovers rapidly from suppression and is probably a climax species on moist sites.

Silvicultural practices for managing the oak-hickory type have been summarized. Establishing the seedling origin of hickory trees is difficult because of seed predators. Although infrequent bumper seed crops usually provide some seedlings, seedling survival is poor under a dense canopy. Because of prolific sprouting ability, hickory reproduction can survive browsing, breakage, drought, and fire. Top dieback and resprouting may occur several times, each successive shoot reaching a larger size and developing a stronger root system than its predecessors. By this process, hickory reproduction gradually accumulates and grows under moderately dense canopies, especially on sites dry enough to restrict reproduction of more tolerant, but more fire or drought-sensitive species.

Wherever adequate hickory advance reproduction occurs, clearcutting results in new sapling stands containing some hickories. Reproduction is difficult to attain if advance hickory regeneration is inadequate, though; then clearcutting will eliminate hickories except for stump sprouts. In theory, light thinnings or shelterwood cuts can be used to create advance hickory regeneration, but this has not been demonstrated.

Damaging agents

editMockernut hickory is extremely sensitive to fire because of the low insulating capacity of the hard, flinty bark. It is not subject to severe loss from disease. The main fungus of hickory is Poria spiculosa, a trunk rot. This fungus kills the bark, which produces a canker, causes heart rot and decay, and can seriously degrade the tree. Mineral streaks and sapsucker-induced streaks also degrade the lumber. In general, the hard, strong, and durable wood of hickories makes them relatively resistant to decay fungi. Most fungi cause little, if any, decay in small, young trees.

Common foliage diseases include leaf mildew and witches' broom (Microstroma juglandis), leaf blotch (Mycosphaerella dendroides), and pecan scab (Cladosporium effusum). Mockernut hickory is host to anthracnose (Gnomonia caryae).

Nuts of all hickory species are susceptible to attack by the hickory nut weevil (Curculio caryae). Another weevil (Conotrachelus aratus) attacks young shoots and leaf petioles. The Curculio species are the most damaging and can destroy 65% of the hickory nut crop. Hickory shuckworms also damage nuts.

The bark beetle (Scolytus quadrispinosus) attacks mockernut hickory, especially in drought years and where hickory species are growing rapidly. The hickory spiral borer (Argilus arcuatus torquatus) and the pecan carpenterworm (Cossula magnifica) are also serious insect enemies of mockernut. The hickory bark beetle probably destroys more sawtimber-size mockernut trees than any other insect. The hickory spiral borer kills many seedlings and young trees, and the pecan carpenterworm degrades both trees and logs. The twig girdler (Oncideres cingulata) attacks both small and large trees; it seriously deforms trees by sawing branches. Sometimes, these girdlers cut hickory seedlings near ground level.

Two casebearers (Acrobasis caryivorella and A. juglandis) feed on buds and leaves; later, they bore into succulent hickory shoots. Larvae of A. caryivorella may destroy entire nut sets. The living-hickory borer (Goes pulcher) feeds on hickory boles and branches throughout the East. Borers commonly found on dying or dead hickory trees or cut logs include:

- Banded hickory borer (Knulliana cincta)

- Long-horned beetle (Saperda discoidea)

- Apple twig borer (Amphicerus bicaudatus)

- Flatheaded ambrosia beetle (Platypus compositus)

- Redheaded ash borer (Neoclytus acuminatus)

- False powderpost beetle (Scobicia bidentata)

Severe damage to hickory lumber and manufactured hickory products is caused by powderpost beetles (Lyctus spp. and Polycanon stoutii). Gall insects (Caryomyia spp.) commonly infest leaves. The fruit-tree leafroller (Archips argyrospila) and the hickory leafroller (Argyrotaenia juglandana) are the most common leaf feeders. The giant bark aphid (Longistigma caryae) is common on hickory bark. This aphid usually feeds on twigs and can cause branch mortality. The European fruit lecanium (Parthnolecanium corni) is common on hickories.

Mockernut is not easily injured by ice glaze or snow, but young seedlings are very susceptible to frost damage. Many birds and animals feed on the nuts of mockernut hickory. This feeding combined with insect and disease problems eliminates the annual nut production, except during bumper seed crop years.

Ecology and uses

editMockernuts are preferred mast for wildlife, particularly squirrels, which eat green nuts. Black bears, foxes, rabbits, beavers, and white-footed mice feed on the nuts, and sometimes the bark. The white-tailed deer browse on foliage and twigs and also feed on nuts. Hickory nuts are a minor source of food for ducks, quail, and turkey.

Mockernut hickory nuts are consumed by many species of birds and other animals, including wood duck, red-bellied woodpecker, red fox, squirrels, beaver, eastern cottontail, eastern chipmunk, turkey, white-tailed deer, white-footed mice, and others. Many insect pests eat hickory leaves and bark. Mockernut hickories also provide cavities for animals to live in, such as woodpeckers, black rat snakes, raccoons, Carolina chickadees, and more. They are also good nesting trees, providing cover for birds with their thick foliage. Animals help disperse seeds so that new hickories can grow elsewhere. Chipmunks, squirrels, and birds do this best. Some fungi grow on mockernut hickory roots, sharing nutrients from the soil.[12]

True hickories provide a large portion of the high-grade hickory used by industry. Mockernut is used for lumber, pulpwood, charcoal, and other fuelwood products. Hickory species are preferred species for fuelwood consumption. Mockernut has the second-highest heating value among the species of hickories. It can be used for veneer, but the low supply of logs of veneer quality is a limiting factor.

Mockernut hickory is used for tool handles requiring high shock resistance. It is used for ladder rungs, athletic goods, agricultural implements, dowels, gymnasium apparatus, poles, shafts, well pumps, and furniture. Lower-grade lumber is used for pallets, blocking, etc. Hickory sawdust, chips, and some solid wood are often used by packing companies to smoke meats;[4] mockernut is the preferred wood for smoking hams.[13] Though mockernut kernels are edible, they are rarely eaten by humans because of their size and because they are eaten by squirrels and other wildlife.[13]

Genetics

editMockernut is a 64-chromosome species, so rarely crosses with 32-chromosome species such as pecan or shellbark hickory. No published information exists concerning population or other genetic studies of this species. Efforts are currently underway to map the genome of pecan in a collaborative effort. The genome map at some point may expand to cover other hickory species.

Hickories are noted for their variability, with many natural hybrids known among North American Carya species. Hickories usually can be crossed successfully within the genus. Geneticists recognize that mockernut hickory hybridizes naturally with C. illinoensis (Carya x schneckii Sarg.) and C. ovata (Carya x collina Laughlin). Mockernut readily hybridizes with tetraploid C. texana.[14] Hybrids generally are shy nut producers or produce nuts that are not filled with a kernel. Numerous exceptions to this rule are known.

Gallery

edit-

Bud break

-

Female flower

-

Bark

References

edit- ^ Stritch, L. (2018). "Carya tomentosa". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T126194480A126194528. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-1.RLTS.T126194480A126194528.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Carya tomentosa". USDA plant database. USDA. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ^ Lewis & Short. tomentum.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Miller, J.H., & Miller, K.V. (1999). Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Champaign, IL: Kings Time Printing.

- ^ Manning, W. E. 1973. The northern limits of the distributions of hickories in New England. Rhodora 75(801):34-35.

- ^ a b Nelson, Thomas C. 1959. Silvical characteristics of mockernut hickory. USDA Forest Service, Station Paper 105. Southeastern Forest Experiment Station, Asheville, NC. 10 p.

- ^ a b c Nelson, Thomas C. 1965. Silvical characteristics of the commercial hickories. USDA Forest Service, Hickory Task Force Report 10. Southeastern Forest Experiment Station, Asheville, NC. 16 p.

- ^ U.S. Department of Agriculture. 1941. Climate and man. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Yearbook of Agriculture. Washington, DC. 1248 p.

- ^ U.S. Department of Commerce, Environmental Science Service Administration. 1968. Climatic atlas of the United States. U.S. Department of Commerce, Environmental Data Service, Washington, DC. 80 p.

- ^ Halls, Lowell K., ed. 1977. Mockernut history, Carya tomentosa. In Southern fruit producing woody plants used by wildlife. p. 142-143. USDA Forest Service, General Technical Report SO-16. Southern Forest Experiment Station, New Orleans, LA.

- ^ a b c U.S. Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service 1975. Soil taxonomy: a basic system of soil classification for making and interpreting soil surveys. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Handbook 436. Washington, DC 754 p.

- ^ Mockernut hickory. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.fcps.edu/islandcreekes/ecology/mockernut_hickory.htm Archived 2011-09-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Little, Elbert L. (1980). The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Trees: Eastern Region. New York: Knopf. p. 356. ISBN 0-394-50760-6.

- ^ Grauke, L. J. "Mockernut Hickory, C. tomentosa".

Sources

edit- Baker, Frederick S. 1949. A revised tolerance table. Journal of Forestry 47:179-181.

- Baker, Whiteford L. 1972. Eastern forest insects. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Miscellaneous Publication 1175. Washington, DC. 642 p.

- Berry, Frederick H., and John A. Beaton. 1972. Decay causes little loss in hickory. USDA Forest Service, Research Note NE-152. Northeastern Forest Experiment Station, Broomall, PA. 4 p.

- Bonner, F. T., and L. C. Maisenhelder. 1974. Carya Nutt. Hickory. In Seeds of woody plants of the United States. p. 269-272. C. S. Schopmeyer, tech. coord. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Handbook 450. Washington, DC.

- Campbell, W. A., and A. F. Verrall. 1956. Fungus enemies of hickory. USDA Forest Service, Hickory Task Force Report 3. Southeastern Forest Experiment Station, Asheville, NC. 12 p.

- Clark, Alexander, III, and W. Henry McNab. 1982. Total tree weight tables for mockernut hickory and white ash in north Georgia. Research Division Georgia Forestry Commission, Georgia Forest Research Paper 33. 11 p.

- Crawford, Hewlette S., R. G. Hooper, and R. F. Harlow. 1976. Woody plants selected by beavers in the Appalachian Ridge and Valley Province. USDA Forest Service, Research Paper NE-346. Northeastern Forest Experiment Station, Broomall, PA. 6 p.

- Cruikshank, James W., and J. F. McCormack. 1956. The distribution and volume of hickory timber. USDA Forest Service, Hickory Task Force Report 5. Southeastern Forest Experiment Station, Asheville, NC. 12 p.

- Eyre, F. H., ed. 1980. Forest cover types of the United States and Canada. Society of American Foresters, Washington, DC. 148 p.

- Fernald, Merritt L. 1950. Gray's manual of botany. Eighth ed. American Book Company, New York. 1632 p.

- Halls, Lowell K., ed. 1977. Mockernut history, Carya tomentosa. In Southern fruit producing woody plants used by wildlife. p. 142-143. USDA Forest Service, General Technical Report SO-16. Southern Forest Experiment Station, New Orleans, LA.

- Heiligmann, Randall B., Mark Golitz, and Martin E. Dale. 1984. Predicting board-foot tree volume from stump diameter for eight hardwood species in Ohio. Ohio Academy Science 84:259-263.

- Hepting, George H. 1971. Diseases of forest and shade trees of the United States. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Handbook 386. Washington, DC. 658 p.

- Jaynes, Richard A. 1974. Hybridizing nut trees. Plants and Gardens 30:67-69.

- Liming, Franklin G., and John P. Johnson. 1944. Reproduction in oak-hickory forest stands in the Missouri Ozarks. Journal of Forestry 42:175-180.

- Little, Elbert L. 1980. The Audubon Society field guide to North American trees, Eastern Region. Alfred A. Knopf, New York. 716 p.

- Lutz, John F. 1955. Hickory for veneer and plywood. USDA Forest Service, Hickory Task Force Report 1. Southeastern Forest Experiment Station, Asheville, NC. 13 p.

- Madden, G. 1978. Selection packing and storage of pecan and hickory propagation wood. Pecan South 5:66-67.

- Madden, G. D., and H. L. Malstrom. 1975. Pecans and hickories. In Advances in fruit breeding. p. 420-438. J. Janick and J. N. Moore, eds. Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana.

- Manning, W. E. 1973. The northern limits of the distributions of hickories in New England. Rhodora 75(801):34-35.

- Martin, Alexander C., Herbert S. Zim, and Arnold L. Nelson. 1951. American wildlife and plants. A guide to wildlife food habits. Dover, New York. 500p.

- Mitchell, A. F. 1970. Identifying the hickories. In International Dendrological Society Yearbook. p. 32-34. International Dendrology Society, London, England.

- Myers, Charles, and David M. Belcher. 1981. Estimating total-tree heights for upland oaks and hickories in southern Illinois. USDA Forest Service, Research Note NC-272. North Central Forest Experiment Station, St. Paul, MN. 3 p.

- Nelson, Thomas C. 1959. Silvical characteristics of mockernut hickory. USDA Forest Service, Station Paper 105. Southeastern Forest Experiment Station, Asheville, NC. 10 p.

- Nelson, Thomas C. 1960. Silvical characteristics of bitternut hickory. USDA Forest Service, Station Paper 111. Southeastern Forest Experiment Station, Asheville, NC. 9 p.

- Nelson, Thomas C. 1965. Mockernut hickory (Carya tomentosa Nutt.). In Silvics of forest trees in the United States. p. 115-118. H. A. Fowells, comp. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Handbook 271. Washington, DC.

- Nelson, Thomas C. 1965. Silvical characteristics of the commercial hickories. USDA Forest Service, Hickory Task Force Report 10. Southeastern Forest Experiment Station, Asheville, NC. 16 p.

- Nixon, Charles M., Wilford W. McClain, and Lonnie P. Hansen. 1980. Six years of hickory seed yields in southeastern Ohio. Journal of Wildlife Management 44:534-539.

- Page, Rufus H., and Lenthall Wyman. 1969. Hickory for charcoal and fuel. USDA Forest Service, Hickory Task Force Report 12. Southeastern Forest Experiment Station, Asheville, NC. 7 p.

- Reed, C. A. 1944. Hickory species and stock studies at the Plant Industry Station, Beltsville, Maryland. Proceedings Northern Nut Growers Association 35:88-115.

- Smith, H. Clay. 1966. Epicormic branching on eight species of Appalachian hardwoods. USDA Forest Service, Research Note NE-53. Northeastern Forest Experiment Station, Broomall, PA. 4 p.

- Trimble, George R. Jr. 1975. Summaries of some silvical characteristics of several Appalachian hardwood trees. USDA Forest Service, General Technical Report NE-16. Northeastern Forest Experiment Station, Upper Darby, PA. 5 p.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. 1941. Climate and man. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Yearbook of Agriculture. Washington, DC. 1248 p.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 1974. Wood handbook: wood as an engineering material. *U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Handbook 72. Washington, DC. 433 p. var. paging.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 1980. Root characteristics of some important trees of eastern forests: a summary of the literature. USDA Forest Service, Eastern Region, Milwaukee, WI. 217 p.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service 1975. Soil taxonomy: a basic system of soil classification for making and interpreting soil surveys. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Handbook 436. Washington, DC 754 p.

- U.S. Department of Commerce, Environmental Science Service Administration. 1968. Climatic atlas of the United States. U.S. Department of Commerce, Environmental Data Service, Washington, DC. 80 p.

- Watt, Richard F., Kenneth A. Brinkman, and B. A. Roach. 1973. Oak-hickory. In Silvicultural systems for the major forest types of the United States. p. 66-69. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Handbook 445. Washington, DC.

- Wiant, Harry V., and David 0. Yandle. 1984. A taper system for predicting height, diameter, and volume of hardwoods. Northern Journal of Applied Forestry 1:24-25.

This article incorporates public domain material from Silvics of North America; volume 2: Hardwoods. Forest Service Agriculture Handbook. Vol. 654. United States Department of Agriculture. 1990.