Menander (/məˈnændər/; Greek: Μένανδρος Menandros; c. 342/41 – c. 290 BC) was a Greek dramatist and the best-known representative of Athenian New Comedy.[1] He wrote 108 comedies[2] and took the prize at the Lenaia festival eight times.[3] His record at the City Dionysia is unknown.

Menander | |

|---|---|

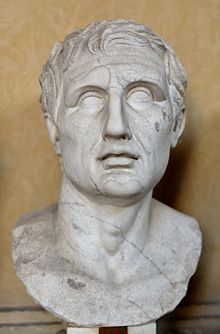

Bust of Menander. Marble, Roman copy of the Imperial era after a Greek original (c. 343–291 BC). | |

| Born | 342/41 BC Kephisia, Athens |

| Died | c. 290 BC (aged 50 – 52) |

| Education | Student of Theophrastus at the Lyceum |

| Genre | New Comedy |

| Notable works | |

He was one of the most popular writers and most highly admired poets in antiquity, but his work was considered lost before the early Middle Ages. It now survives only in Latin-language adaptations by Terence and Plautus and, in the original Greek, in highly fragmentary form, most of which were discovered on papyrus in Egyptian tombs during the early to mid-20th-century. In the 1950s, to the great excitement of Classicists, it was announced that a single play by Menander, Dyskolos, had finally been rediscovered in the Bodmer Papyri intact enough to be performed.

Life and work edit

Menander was the son of well-to-do parents; his father Diopeithes is identified by some with the Athenian general and governor of the Thracian Chersonese known from the speech of Demosthenes De Chersoneso. He presumably derived his taste for comic drama from his uncle Alexis.[4][5]

He was the friend, associate, and perhaps pupil of Theophrastus, and was on intimate terms with the Athenian dictator Demetrius of Phalerum.[6] He also enjoyed the patronage of Ptolemy Soter, the son of Lagus, who invited him to his court. But Menander, preferring the independence of his villa in the Piraeus and the company of his mistress Glycera, refused.[7] According to the note of a scholiast on the Ibis of Ovid, he drowned while bathing,[8] and his countrymen honored him with a tomb on the road leading to Athens, where it was seen by Pausanias.[9] Numerous supposed busts of him survive, including a well-known statue in the Vatican, formerly thought to represent Gaius Marius.[4]

His rival in dramatic art (and supposedly in the affections of Glycera) was Philemon, who appears to have been more popular. Menander, however, believed himself to be the better dramatist, and, according to Aulus Gellius,[10] used to ask Philemon: "Don't you feel ashamed whenever you gain a victory over me?" According to Caecilius of Calacte (Porphyry in Eusebius, Praeparatio evangelica[11]) Menander was accused of plagiarism, as his The Superstitious Man was taken from The Augur of Antiphanes,[4] but reworkings and variations on a theme of this sort were commonplace and so the charge is a complicated one.

How long complete copies of his plays survived is unclear, although 23 of them, with commentary by Michael Psellus, were said to still have been available in Constantinople in the 11th century. He is praised by Plutarch (Comparison of Menander and Aristophanes)[12] and Quintilian (Institutio Oratoria), who accepted the tradition that he was the author of the speeches published under the name of the Attic orator Charisius.[13]

An admirer and imitator of Euripides, Menander resembles him in his keen observation of practical life, his analysis of the emotions, and his fondness for moral maxims, many of which became proverbial: "The property of friends is common," "Whom the gods love die young," "Evil communications corrupt good manners" (from the Thaïs, quoted in 1 Corinthians 15:33). These maxims (chiefly monostichs) were afterwards collected, and, with additions from other sources, were edited as Menander's One-Verse Maxims, a kind of moral textbook for the use of schools.[4]

The single surviving speech from his early play Drunkenness is an attack on the politician Callimedon, in the manner of Aristophanes, whose bawdy style was adopted in many of his plays.[citation needed]

Menander found many Roman imitators. Eunuchus, Andria, Heauton Timorumenos and Adelphi of Terence (called by Caesar "dimidiatus Menander") were avowedly taken from Menander, but some of them appear to be adaptations and combinations of more than one play. Thus in the Andria were combined Menander's The Woman from Andros and The Woman from Perinthos, in the Eunuchus, The Eunuch and The Flatterer, while the Adelphi was compiled partly from Menander and partly from Diphilus. The original of Terence's Hecyra (as of the Phormio) is generally supposed to be, not by Menander, but Apollodorus of Carystus. The Bacchides and Stichus of Plautus were probably based upon Menander's The Double Deceiver and Brotherly-Loving Men, but the Poenulus does not seem to be from The Carthaginian, nor the Mostellaria from The Apparition, in spite of the similarity of titles. Caecilius Statius, Luscius Lanuvinus, Turpilius and Atilius also imitated Menander. He was further credited with the authorship of some epigrams of doubtful authenticity; the letters addressed to Ptolemy Soter and the discourses in prose on various subjects mentioned by the Suda[14] are probably spurious.[4]

Loss of his work edit

Most of Menander's work did not survive the Middle Ages, except as short fragments. Federico da Montefeltro's library at Urbino reputedly had "tutte le opere", a complete works, but its existence has been questioned and there are no traces after Cesare Borgia's capture of the city and the transfer of the library to the Vatican.[15]

Until the end of the 19th century, all that was known of Menander were fragments quoted by other authors and collected by Augustus Meineke (1855) and Theodor Kock, Comicorum Atticorum Fragmenta (1888). These consist of some 1650 verses or parts of verses, in addition to a considerable number of words quoted from Menander by ancient lexicographers.[4]

20th-century discoveries edit

This situation changed abruptly in 1907, with the discovery of the Cairo Codex, which contained large parts of the Samia, the Perikeiromene, and the Epitrepontes; a section of the Heros; and another fragment from an unidentified play. A fragment of 115 lines of the Sikyonioi had been found in the papier mache of a mummy case in 1906.

In 1959, the Bodmer papyrus was published containing Dyskolos, more of the Samia, and half of the Aspis. In the late 1960s, more of the Sikyonioi was found as filling for two more mummy cases; this proved to be drawn from the same manuscript as the discovery in 1906, which had clearly been thoroughly recycled.[16]

Other papyrus fragments continue to be discovered and published.[17]

In 2003, a palimpsest manuscript, in Syriac writing of the 9th century, was found where the reused parchment comes from a very expensive 4th-century Greek manuscript of works by Menander. The surviving leaves contain parts of the Dyskolos and 200 lines of another piece by Menander, so far unpublished, titled Titthe.[18][19][20]

Famous quotations edit

In his First Epistle to the Corinthians, Paul the Apostle quotes Menander in the text "Bad company corrupts good character",[21] which probably comes from his play Thais; according to 5th century Christian historian Socrates Scholasticus, Menander derived this from Euripides.[22][23]

"He who labors diligently need never despair, for all things are accomplished by diligence and labor." — Menander

"Ἀνερρίφθω κύβος" (anerriphtho kybos), best known in English as "the die is cast" or "the die has been cast", from the mis-translated Latin "iacta alea est" (itself better-known in the order "Alea iacta est"); a correct translation is "let the die be cast" (meaning "let the game be ventured"). The Greek form was famously quoted by Julius Caesar upon committing his army to civil war by crossing the River Rubicon. The popular form "the die is cast" is from the Latin iacta alea est, a mistranslation by Suetonius, 121 AD. According to Plutarch, the actual phrase used by Julius Caesar at the crossing of the Rubicon was a quote in Greek from Menander's play Arrhephoros, with the different meaning "Let the die be cast!".[24] See discussion at "the die is cast" and "Alea iacta est".

He [Caesar] declared in Greek with loud voice to those who were present 'Let the die be cast' and led the army across. (Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 60.2.9)[25]

Lewis and Short,[26] citing Casaubon and Ruhnk, suggest that the text of Suetonius should read Jacta alea esto, which they translate as "Let the die be cast!", or "Let the game be ventured!". This matches Plutarch's third-person perfect imperative ἀνερρίφθω κύβος (anerrhiphtho kybos).

According to Gregory Hayes' Translation of Meditations by Marcus Aurelius, Menander is also known for the quote/proverb: "a rich man owns so many goods he has no place to shit.” (Meditations, V:12)[27]

Another well known quote by Menander is "Whom the gods love dies young".[28]

Comedies edit

Menander's comedies were very different from the Old Comedies of Aristophanes. New Greek Comedies usually would have two lovers, a blocking character, and a helpful servant. They typically ended with a wedding or happy ending. They were much more of a "higher brow" comedy than Old Greek comedy. They were also more realistic.

More-complete plays edit

- Aspis ("The Shield"; about half)

- Dyskolos ("The Grouch" or "Old Cantankerous"; best preserved play)

- Epitrepontes ("Men at Arbitration"; most)

- Misoumenos ("The Hated Man"; about a third)

- Perikeiromene ("Girl who has her hair cropped"; George Bernard Shaw suggested Rape of the Locks, after Alexander Pope; about half)

- Samia ("Girl from Samos"; most)

- Sikyonioi or Sikyonios ("Sicyonian(s)"; about a third)

Only fragments available edit

- Adelphoi ("The Brothers")

- Anatithemene, or Messenia ("The Woman From Messene")

- Andria ("The Woman From Andros")

- Androgynos ("Hermaphrodite"), or Kres ("The Cretan")

- Anepsioi ("Cousins")

- Aphrodisia ("The Erotic Arts"), or Aphrodisios

- Apistos ("Unfaithful", or "Unbelieving")

- Arrhephoros ("The Bearer of Ritual Objects"), or Auletris ("The Female Flute-Player")

- Auton Penthon ("Grieving For Him")

- Boiotis ("The Woman From Boeotia")

- Chalkeia ("The Chalceia Festival"), or Chalkis ("The Copper Pot")

- Chera ("The Widow")

- Daktylios ("The Ring")

- Dardanos ("Dardanus")

- Deisidaimon ("The Superstitious Man")

- Demiourgos ("The Demiurge")

- Didymai ("Twin Sisters")

- Dis Exapaton ("Double Deceiver")

- Empimpramene ("Woman On Fire")

- Encheiridion ("The Dagger")

- Epangellomenos ("The Man Making Promises")

- Ephesios ("The Man From Ephesus")

- Epikleros ("The Heiress")

- Eunouchos ("The Eunuch")

- Georgos ("The Farmer")

- Halieis ("The Fishermen")

- Heauton Timoroumenos ("Torturing Himself")

- Heniochos ("The Charioteer")

- Heros ("The Hero")

- Hiereia ("The Priestess")

- Hippokomos ("The Horse-Groom")

- Homopatrioi ("People Having The Same Father")

- Hydria ("The Water-Pot")

- Hymnis ("Hymnis")

- Hypobolimaios ("The Changeling"), or Agroikos ("The Country-Dweller")

- Imbrioi ("People From Imbros")

- Kanephoros ("The Ritual-Basket Bearer")

- Karchedonios ("The Carthaginian Man")

- Karine ("The Woman From Caria")

- Katapseudomenos ("The False Accuser")

- Kekryphalos ("The Hair-Net")

- Kitharistes ("The Harp-Player")

- Knidia ("The Woman From Cnidos")

- Kolax ("The Flatterer" or "The Toady")

- Koneiazomenai ("Women Drinking Hemlock")

- Kybernetai ("The Helmsmen")

- Leukadia ("The Woman from Leukas")

- Lokroi ("Men From Locris")

- Menagyrtes ("The Beggar-Priest of Rhea")

- Methe ("Drunkenness")

- Misogynes ("The Woman-Hater")

- Naukleros ("The Ship's Captain")

- Nomothetes ("The Lawgiver" or "Legislator")

- Olynthia ("The Woman From Olynthos")

- Orge ("Anger")

- Paidion ("Little Child")

- Pallake ("The Concubine")

- Parakatatheke ("The Deposit")

- Perinthia ("The Woman from Perinthos")

- Phanion ("Phanion")

- Phasma ("The Phantom, or Apparition")

- Philadelphoi ("Brotherly-Loving Men")

- Plokion ("The Necklace")

- Poloumenoi ("Men Being Sold", or "Men For Sale")

- Proenkalon ("The Pregnancy")

- Progamoi ("People About to Get Married")

- Pseudherakles ("The Fake Hercules")

- Psophodees ("Frightened By Noise")

- Rhapizomene ("Woman Getting Her Face Slapped")

- Storfiappos ("The Spinner")

- Stratiotai ("The Soldiers")

- Synaristosai ("Women Who Eat Together At Noon"; "The Ladies Who Lunch")

- Synepheboi ("Fellow Adolescents")

- Synerosa ("Woman In Love")

- Thais ("Thaïs")

- Theophoroumene ("The Girl Possessed by a God")

- Thesaurus ("The Treasure")

- Thettale ("The Woman From Thessaly")

- Thrasyleon ("Thrasyleon")

- Thyroros ("The Doorkeeper")

- Titthe ("The Wet-Nurse")

- Trophonios ("Trophonius")

- Xenologos ("Enlisting Foreign Mercenaries")

Standard editions edit

The standard edition of the least-well-preserved plays of Menander is Kassel-Austin, Poetarum Comicorum Graecorum vol. VI.2. For the better-preserved plays, the standard edition is now Arnott's 3-volume Loeb. A complete text of these plays for the Oxford Classical Texts series was left unfinished by Colin Austin at the time of his death;[29] the OCT edition of Harry Sandbach, published in 1972 and updated in 1990, remains in print.[30]

See also edit

Notes edit

- ^ Konstan, David (2010). Menander of Athens. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 3–6. ISBN 978-0199805198.

- ^ Suidas μ 589

- ^ Apollodorus: Chronicle, fr.43

- ^ a b c d e f One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Freese, John Henry (1911). "Menander". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 109–110.

- ^ 'A Short History of Comedy', [1]Prolegomena De Comoedia, 3

- ^ Phaedrus: Fables, 5.1

- ^ Alciphron: Letters, 2.3–4

- ^ Scholiast on Ibis.591

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece, 1.2.2

- ^ Gellius: Noctes Attica, 17.4

- ^ Eusebius: Praeparatio Evangelica, Book 10, Chapter 3

- ^ Plutarch: Moralia, 853–854

- ^ Quintilian: Institutio Oratoria, 10.1.69

- ^ Suda, M.589

- ^ Jacob Burckhardt, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, 1860. Paragraph 8 of this subchapter, but see print editions (such as Irene Gordon's (Mentor 1960) p. 158) for Burckhadt's footnote speculating on future rediscoveries.

- ^ Menander: Plays and Fragments, tr. Norma Miller. Penguin 1987, p.15

- ^ Sommerstein, Alan (6 December 2012). "From Mount Sinai to Michigan: the rediscovery of Menander's Epitrepontes (part 4)". University of Nottingham.

- ^ Dieter Harlfinger, Warten auf Menander im Vatikan. 400 griechische Komödienverse in einer syrischen Palimpsest-Handschrift entdeckt, in: Forum Classicum, 2004. See here for an English translation.

- ^ F. D’Aiuto: Graeca in codici orientali della Biblioteca Vaticana (con i resti di un manoscritto tardoantico delle commedie di Menandro), in: Tra Oriente e Occidente. Scritture e libri greci fra le regioni orientali di Bisanzio e l’Italia, a cura di Lidia Perria, Rom 2003 (= Testi e studi bizantino-neoellenici XIV), S. 227–296 (esp. 266–283 and plates 13–14)

- ^ Miles, Sarah (2014) 'Menander. C. Austin (ed.) Menander. Eleven Plays. (Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society, Supplementary Volume 37.) Pp. xviii + 84. Cambridge : The Cambridge Philological Society, 2013. Paper, Classical review., 64 (02). pp. 409-411.

- ^ 1 Cor 15:33

- ^ Socrates Scholasticus, Ecclesiastical History, Book 3, Chapter 16

- ^ intertextual.bible/text/menander-thais-218-1-corinthians-15.33

- ^ Perseus Digital Library Plut. Pomp. 60.2

- ^ See also Plutarch's Life of Caesar 32.8.4 and Sayings of Kings & Emperors 206c.

- ^ Online Dictionary: alea, Lewis and Short at the Perseus Project. See bottom of section I.

- ^ http://seinfeld.co/library/meditations.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Menander, Monosticha - Sententiae, 425

- ^ "Colin Austin obituary". The Guardian. 2010-09-06. Archived from the original on 2023-07-26.

- ^ OUP Edition of Menander Archived 2015-05-26 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading edit

- Cox, Cheryl Anne. (2002). "Crossing Boundaries Through Marriage in Menander’s Dyskolos." Classical Quarterly 52: 391–394.

- Csapo, E. (1999). "Performance and Iconographic Tradition in the Illustrations of Menander." Syllecta Classica 6: 154–188.

- Frost, K. B. (1988). Exits and Entrances in Menander. Oxford: Clarendon.

- Glazebrook, Allison. (2015). "A Hierarchy of Violence? Sex Slaves, Parthenoi, and Rape in Menander's Epitrepontes." Helios, 42(1): 81-101.

- Goldberg, Sander M. (1980). The Making of Menander’s Comedy. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press.

- Gutzwiller, Kathryn, and Ömer Çelik. (2012). “New Menander Mosaics from Antioch.” American Journal of Archaeology 116:573–623.

- Nervegna, Sebastiana. (2013). Menander in Antiquity: The Contexts of Reception. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Papaioannou, Sophia and Antonis K. Petrides eds., (2010). New Perspectives on Postclassical Comedy. Pierides, 2. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Traill, Ariana. (2008). Women and the Comic Plot in Menander. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Walton, Michael, and Peter D. Arnott. (1996). Menander and the Making of Comedy. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

External links edit

- Works by Menander at Faded Page (Canada)

- An English translation of the Dyskolos.

- Dyskolos, translated by G. Theodoridis

- Perikeiromene, translated by F. G. Allinson

- Menander: Monosticha / Sententiae / Einzelverse – Sentences from Menander's work in the original Greek and translated in Latin and German

- SORGLL: Menander, Dyskolos, 711–747; read by Mark Miner