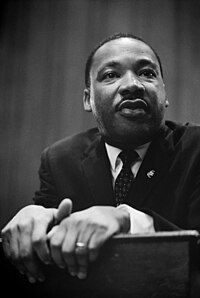

Martin Luther King Jr. Day (officially Birthday of Martin Luther King Jr.,[1] and often referred to shorthand as MLK Day) is a federal holiday in the United States observed on the third Monday of January each year. King was chief spokesperson for nonviolent activism in the Civil Rights Movement, which protested racial discrimination in federal and state law and civil society. The movement led to several groundbreaking legislative reforms in the United States.

Born in 1929, Martin Luther King Jr.'s actual birthday is January 15 (which in 1929 fell on a Tuesday). The earliest Monday for this holiday is January 15 and the latest is January 21. The Monday observance is similar for those federal holidays which fall under the Uniform Monday Holiday Act.

The campaign for a federal holiday in King's honor began soon after his assassination in 1968. President Ronald Reagan signed the holiday into law in 1983, and it was first observed three years later on January 20, 1986. At first, some states resisted observing the holiday as such, giving it alternative names or combining it with other holidays. Official observance in each state's law as well as federal law occurred in 2000.

History edit

Proposals edit

The idea of Martin Luther King Jr. Day as a holiday was promoted by labor unions in contract negotiations.[2] After King's death, Representative John Conyers[3] (a Democrat from Michigan) and Senator Edward Brooke (a Republican from Massachusetts) introduced a bill in Congress to make King's birthday a national holiday. The bill first came to a vote in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1979. However, it fell five votes short of the number needed for passage.[4] Two of the main arguments mentioned by opponents were that a paid holiday for federal employees would be too expensive and that a holiday to honor a private citizen would be contrary to longstanding tradition (King had never held public office).[4] Only two other figures have national holidays in the U.S. honoring them: George Washington and Christopher Columbus.

Soon after, the King Center turned to support from the corporate community and the general public. The success of this strategy was cemented when musician Stevie Wonder released the single "Happy Birthday" to popularize the campaign in 1980 and hosted the Rally for Peace Press Conference in 1981. Six million signatures were collected for a petition to Congress to pass the law, termed by a 2006 article in The Nation as "the largest petition in favor of an issue in U.S. history".[2]

Senators Jesse Helms and John Porter East (both North Carolina Republicans) led the opposition to the holiday and questioned whether King was important enough to receive such an honor. Helms criticized King's opposition to the Vietnam War and accused him of espousing "action-oriented Marxism".[5] Helms led a filibuster against the bill and on October 3, 1983, submitted a 300-page document to the Senate alleging that King had associations with communists. Democratic New York Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan declared Helms' document a "packet of filth", threw it on the Senate floor, and stomped on it.[6][7]

Federal passage edit

President Ronald Reagan originally opposed the holiday, citing cost concerns. When asked to comment on Helms' accusations that King was a communist, the president said "We'll know in thirty-five years, won't we", referring to the eventual release of FBI surveillance tapes that had previously been sealed.[8] But on November 2, 1983, Reagan signed a bill into law, proposed by Representative Katie Hall of Indiana, to create a federal holiday honoring King.[9][10] The final vote in the House of Representatives on August 2, 1983, was 338–90 (242–4 in the House Democratic Caucus and 89–77 in the House Republican Conference) with 5 members voting present or abstaining,[11][5] while the final vote in the Senate on October 19, 1983, was 78–22 (41–4 in the Senate Democratic Caucus and 37–18 in the Senate Republican Conference),[12][13] both veto-proof margins. The holiday was observed for the first time on January 20, 1986.[10] It is observed on the third Monday of January.[14]

The bill also established the "Martin Luther King, Jr. Federal Holiday Commission"[10] to oversee observance of the holiday, and Coretta Scott King, King's wife, was made a member of this commission for life by President George H. W. Bush in May 1989.[15][16]

State-level passage edit

Although the federal holiday honoring King was signed into law in 1983 and took effect three years later, not every U.S. state chose to observe the January holiday at the state level[3] until 1991, when the New Hampshire legislature created "Civil Rights Day" and abolished its April "Fast Day".[17] In 1999, New Hampshire became the last state to name a holiday after King, which they first celebrated in January 2000 – the first nationwide celebration of the day with this name.[18]

In 1986, Arizona Governor Bruce Babbitt, a Democrat, created a paid state MLK holiday in Arizona by executive order just before he left office, but in 1987, his Republican successor Evan Mecham, citing an attorney general's opinion that Babbitt's order was illegal, reversed Babbitt's decision days after taking office.[19] Later that year, Mecham proclaimed the third Sunday in January to be "Martin Luther King Jr./Civil Rights Day" in Arizona, albeit as an unpaid holiday. This proposal was rejected by the state Senate the following year.[20] In 1990, Arizona voters were given the opportunity to vote on giving state employees a paid MLK holiday. That same year, the National Football League threatened to move Super Bowl XXVII, which was planned for Arizona in 1993, if the MLK holiday was voted down.[21] In the November 1990 election, the voters were offered two King Day options: Proposition 301, which replaced Columbus Day on the list of paid state holidays, and Proposition 302, which merged Lincoln's and Washington's birthdays into one paid holiday to make room for MLK Day. Both measures failed to pass, with only 49% of voters approving Prop 302, the more popular of the two options; although some who voted "no" on 302 voted "yes" on Prop 301.[22] Consequently, the state lost the chance to host Super Bowl XXVII, which was subsequently held at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, California.[21] In a 1992 referendum, the voters, this time given only one option for a paid King Day, approved state-level recognition of the holiday.[23]

On May 2, 2000, South Carolina governor Jim Hodges signed a bill to make King's birthday an official state holiday. South Carolina was the last state to recognize the day as a paid holiday for all state employees. Before the bill, employees could choose between celebrating Martin Luther King Jr. Day or one of three Confederate holidays.[24]

Alternative names edit

While all states now observe the holiday, some did not name the day after King. For example, in New Hampshire, the holiday was known as "Civil Rights Day" until 1999, when the State Legislature voted to change the name of the holiday to Martin Luther King Day.[25]

Several additional states have chosen to combine commemorations of King's birthday with other observances:

- In Alabama: "Robert E. Lee/Martin Luther King Birthday".[26]

- In Arizona: "Martin Luther King Jr./Civil Rights Day".[27]

- In Arkansas: it was known as "Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Birthday and Robert E. Lee's Birthday" from 1985 to 2017. Legislation in March 2017 changed the name of the state holiday to "Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Birthday" and moved the commemoration of Lee to October.

- In Idaho: "Martin Luther King Jr.–Idaho Human Rights Day".[28]

- In Mississippi: "Martin Luther King's and Robert E. Lee's Birthdays".[29]

- In New Hampshire: "Martin Luther King Jr. Civil Rights Day".[30]

- In Virginia: it was known as Lee–Jackson–King Day, combining King's birthday with the established Lee–Jackson Day.[31] In 2000, Lee–Jackson Day was moved to the Friday before Martin Luther King Jr. Day, establishing Martin Luther King Jr. Day as a holiday in its own right.[32] Lee-Jackson Day was eliminated in 2020.[33]

- In Wyoming: it is known as "Martin Luther King Jr./Wyoming Equality Day". Liz Byrd, the first black woman in the Wyoming legislature, introduced a bill in 1991 for Wyoming to recognize MLK day as a paid state holiday; however, she compromised on the name because her peers would not pass it otherwise.[34]

Observance edit

Workplace leave edit

Overall, as of 2019, 45% of employers gave employees the day off.[35][unreliable source?] The reasons for not providing the day off have varied, ranging from the recent addition of the holiday to its occurrence just two weeks after the week between Christmas and New Year's Day, when many businesses are closed for part or all of it. The New York Stock Exchange and NASDAQ both close for trading, and banks are generally closed. Additionally, many schools and places of higher education are closed for classes; others remain open but may hold seminars or celebrations of King's message. The observance of MLK Day has led to some colleges and universities extending their Christmas break to include the day as part of the break. Some employers use MLK Day as a floating or movable holiday.[36]

MLK Day of Service edit

The national "Martin Luther King, Jr., National Day of Service"[37] was started by former Pennsylvania U.S. Senator Harris Wofford and Atlanta Congressman John Lewis, who co-authored the King Holiday and Service Act. The federal legislation challenges Americans to transform the King Holiday into a day of citizen action volunteer service in honor of King. The federal legislation was signed into law by President Bill Clinton on August 23, 1994. Since 1996, Wofford's former state office director, Todd Bernstein, has been directing the annual Greater Philadelphia King Day of Service,[38] the largest event in the nation honoring King.[39]

Since 1994, the day of service has been coordinated nationally by AmeriCorps, a federal agency, which provides grants to organizations that coordinate service activities on MLK Day.[40]

The only other official national day of service in the U.S., as designated by the government, is September 11 National Day of Service (9/11 Day).[41]

Speeches edit

Cesar Chavez campaigned with him to call attention to the economic needs of farmworkers in the United States.[42] Chavez used his speech on this day in 1990 to again call attention to the similarity between his campaign regarding pesticide issues and King's campaigns.[42] He later was honored with the creation of Cesar Chavez Day in imitation of this holiday.[43]

Outside the United States edit

Canada edit

The City of Toronto government in Ontario officially recognizes Martin Luther King Jr. Day, although not as a paid holiday: all government services and businesses remain open.[44] The Ottawa municipal government in Ontario officially began observing this national holiday on January 26, 2005.[45]

Israel edit

In 1984, during a visit by the U.S. Sixth Fleet, Navy chaplain Rabbi Arnold Resnicoff conducted the first Israeli presidential ceremony in commemoration of Martin Luther King Jr. Day, held in the President's Residence, Jerusalem. Aura Herzog, wife of Israel's then-President Chaim Herzog, noted that she was especially proud to host this special event, because Israel had a national forest in honor of King, and that Israel and King shared the idea of "dreams."[46] Resnicoff continued this theme in his remarks during the ceremony, quoting the verse from Genesis, spoken by the brothers of Joseph when they saw their brother approach, "Behold the dreamer comes; let us slay him and throw him into the pit, and see what becomes of his dreams." Resnicoff noted that, from time immemorial, there have been those who thought they could kill the dream by slaying the dreamer, but – as the example of King's life shows – such people are always wrong.[47]

Japan edit

Martin Luther King Jr. Day is observed in the Japanese city of Hiroshima. In January 2005, Mayor Tadatoshi Akiba held a special banquet at the mayor's office as an act of unifying his city's call for peace with King's message of human rights.[48]

Netherlands edit

Every year since 1987, the Dr. Martin Luther King Tribute and Dinner has been held in Wassenaar, The Netherlands.[49] The Tribute includes young people and veterans of the Civil Rights Movement as well as music. It always ends with everyone holding hands in a circle and singing "We Shall Overcome". The Tribute is held on the last Sunday in January.[50]

Dates edit

1986–2103

Observed on the third Monday in January.

| Date | Years | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 21 | 1991 | 2002 | 2008 | 2013 | 2019 | 2030 | 2036 | 2041 | 2047 | 2058 | 2064 | 2069 | 2075 | 2086 | 2092 | 2097 | |||||

| January 20 | 1986 | 1992 | 1997 | 2003 | 2014 | 2020 | 2025 | 2031 | 2042 | 2048 | 2053 | 2059 | 2070 | 2076 | 2081 | 2087 | 2098 | ||||

| January 19 | 1987 | 1998 | 2004 | 2009 | 2015 | 2026 | 2032 | 2037 | 2043 | 2054 | 2060 | 2065 | 2071 | 2082 | 2088 | 2093 | 2099 | ||||

| January 18 | 1988 | 1993 | 1999 | 2010 | 2016 | 2021 | 2027 | 2038 | 2044 | 2049 | 2055 | 2066 | 2072 | 2077 | 2083 | 2094 | 2100 | ||||

| January 17 | 1994 | 2000 | 2005 | 2011 | 2022 | 2028 | 2033 | 2039 | 2050 | 2056 | 2061 | 2067 | 2078 | 2084 | 2089 | 2095 | 2101 | ||||

| January 16 | 1989 | 1995 | 2006 | 2012 | 2017 | 2023 | 2034 | 2040 | 2045 | 2051 | 2062 | 2068 | 2073 | 2079 | 2090 | 2096 | 2102 | ||||

| January 15 | 1990 | 1996 | 2001 | 2007 | 2018 | 2024 | 2029 | 2035 | 2046 | 2052 | 2057 | 2063 | 2074 | 2080 | 2085 | 2091 | 2103 | ||||

See also edit

- Blue Monday (date), which generally coincides with Martin Luther King Jr. Day

- Civil rights movement in popular culture

- List of African-American holidays

General holidays edit

- List of holidays by country

- List of holidays commemorating individuals

- List of multinational festivals and holidays

- Public holidays in the United States

Volunteer day events edit

References edit

- ^ "Federal Holidays". Opm.gov. Archived from the original on July 10, 2015. Retrieved January 20, 2014.

- ^ a b Jones, William P. (January 30, 2006). "Working-Class Hero". The Nation. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

- ^ a b Blakemore, Erin (January 10, 2018). "The Fight for Martin Luther King, Jr. Day". History.com. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Wolfensberger, Don (January 14, 2008). "The Martin Luther King Jr. Holiday: The Long Struggle in Congress, An Introductory Essay" (PDF). Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2011. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ a b Dewar, Helen (October 4, 1983). "Helms Stalls King's Day in Senate". The Washington Post. p. A01. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ Romero, Frances (January 18, 2010). "A Brief History of Martin Luther King Jr. Day". Time. Archived from the original on January 20, 2009.

- ^ Courtwright, David T. (2010). No Right Turn: Conservative Politics in a Liberal America. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-674-04677-1. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ^ Younge, Gary (September 2–9, 2013). "The Misremembering of 'I Have a Dream'". The Nation. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved April 12, 2015.

- ^ Woolley, John T.; Gerhard Peters (November 2, 1983). "Ronald Reagan: Remarks on Signing the Bill Making the Birthday of Martin Luther King Jr. a National Holiday". The American Presidency Project. Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ a b c Pub. L. 98–399, 98 Stat. 1475, enacted August 27, 1984

- ^ "TO SUSPEND THE RULES AND PASS H.R. 3706, A BILL AMENDING TITLE 5, UNITED STATES CODE TO MAKE THE BIRTHDAY OF MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., A LEGAL PUBLIC HOLIDAY. (MOTION PASSED;2/3 REQUIRED)". Archived from the original on May 20, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ "TO PASS H.R. 3706. (MOTION PASSED) SEE NOTE(S) 19". Archived from the original on May 20, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ Dewar, Helen (October 20, 1983). "Solemn Senate Votes For National Holiday Honoring Rev. King". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 23, 2019. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- ^ May, Ashley (January 18, 2019). "What is open and closed on Martin Luther King Jr. Day?". USA Today. Archived from the original on January 18, 2019. Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- ^ Woolley, John T.; Gerhard Peters (May 17, 1989). "George Bush: Remarks on Signing the Martin Luther King Jr. Federal Holiday Commission Extension Act". The American Presidency Project. Archived from the original on October 2, 2012. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ Pub. L. 101–30, 103 Stat. 60, enacted May 17, 1989

- ^ Gilbreth, Donna (1997). "Rise and Fall of Fast Day". New Hampshire State Library. Archived from the original on January 2, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

- ^ "N.H.'s Martin Luther King Jr. Day Didn't Happen Without A Fight". New Hampshire Public Radio. August 27, 2013. Archived from the original on August 15, 2014. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ Ye Hee Lee, Michelle (January 15, 2012). "Recalling Arizona's struggle for MLK holiday". The Arizona Republic. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ "Civil Rights Day in United States". timeanddate.com. Time and Date AS. Archived from the original on March 29, 2015. Retrieved April 12, 2015.

- ^ a b "tucsonsentinel.com". tucsonsentinel.com. Archived from the original on February 5, 2013. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ Shumway, Jim (November 26, 1990). "STATE OF ARIZONA OFFICIAL CANVASS – GENERAL ELECTION – November 6, 1990" (PDF). Arizona Secretary of State ~ Home Page. Arizona Secretary of State. p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 17, 2015. Retrieved April 11, 2015.

- ^ Reingold, Beth (2000). Representing Women: Sex, Gender, and Legislative Behavior in Arizona and California. Univ of North Carolina Press. pp. 66–. ISBN 9780807848500. Retrieved May 4, 2014.

- ^ The History of Martin Luther King Day Archived July 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Infoplease

- ^ Goldberg, Carey (May 26, 1999). "Contrarian New Hampshire To Honor Dr. King, at Last". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 11, 2012. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

- ^ "Calendar". Alabama.gov. Archived from the original on February 5, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- ^ "1–301. Holidays enumerated". Arizona Legislature. Archived from the original on January 10, 2008. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- ^ "TItle 73". Idaho.gov. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ^ "State Holidays". MS.gov. Archived from the original on June 18, 2021. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- ^ "CHAPTER 288 HOLIDAYS". New Hampshire General Court. Archived from the original on April 9, 2008. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- ^ Petrie, Phil W. (May–June 2000). "The MLK holiday: Branches work to make it work". The New Crisis. Archived from the original on January 19, 2015. Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- ^ Duran, April (April 10, 2000). "Virginia creates holiday honoring Dr. Martin Luther King Jr". On The Lege. Virginia Commonwealth University. Archived from the original on July 11, 2010. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

- ^ "New state laws that go into effect July 1". CBS 19 News. Charlottesville, Virginia. July 1, 2020. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ "Liz Byrd, First Black Woman in Wyoming's Legislature | WyoHistory.org". www.wyohistory.org. Archived from the original on January 2, 2020. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ "Does Observing Martin Luther King Jr. Day Align With Your Company Values?". Yahoo Video. January 14, 2021. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ Stewart, Jocelyn (January 16, 2006). "MLK Day's crafters urged a day of meaning, service". Contra Costa Times.

- ^ "Volunteer opportunities and resources for organizing an MLK Day of Service event". Martin Luther King, Jr. Day of Service homepage. Corporation for National and Community Service. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018. Retrieved January 16, 2018.

- ^ "Greater Philadelphia Martin Luther King Day of Service". Global Citizen. Archived from the original on June 30, 2009. Retrieved January 16, 2007.

- ^ Moore, Doug (January 16, 2011). "MLK events in Missouri form man's legacy". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Archived from the original on January 20, 2011.

- ^ "About the MLK Day of Service". Corporation for National and Community Service. Archived from the original on September 17, 2020. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ "President Proclaims Sept. 11 Patriot Day and National Day of Service, Remembrance". U.S. DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE. Archived from the original on May 3, 2021. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ a b "Biography: Martin Luther King Jr. Praised Cesar Chavez for His 'Indefatigable Work' – UFW". October 3, 2019. Archived from the original on December 1, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ "California: Chavez Holiday - Rural Migration News | Migration Dialogue". Archived from the original on July 13, 2020. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ Miller, David (2008). "City of Toronto Proclamation". City of Toronto government. Archived from the original on July 7, 2012.

- ^ "City of Ottawa observes Martin Luther King Day for first time in 2005 | CBC News". Archived from the original on October 1, 2020. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

- ^ The Jewish Week & The American Examiner, pg 37, February 3, 1986.

- ^ "Arnold Resnicoff". Library of Congress Veterans History Project Oral History. May 2010. Archived from the original on November 18, 2018. Retrieved January 16, 2017. At 1 hour 37 Min.

- ^ "Mayor's Speech at U.S. Conference of Mayors' Luncheon in commemoration of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr". city.hiroshima.lg.jp. Archived from the original on June 5, 2016. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- ^ "Martin Luther King, Jr. Tribute Dinner". U.S. Embassy & Consulate in the Netherlands. January 30, 2017. Archived from the original on March 31, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ^ "Annual Tribute and Dinner in Honour of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr". The Hague Online. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

Further reading edit

- "Colleges and universities that don't observe the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. 19 (19): 26–27. Spring 1998. doi:10.2307/2998887. JSTOR 2998887.

- Weiss, Jana (2017). "Remember, Celebrate, and Forget? The Martin Luther King Day and the Pitfalls of Civil Religion", Journal of American Studies, Remember, Celebrate, and Forget? The Martin Luther King Day and the Pitfalls of Civil Religion .

External links edit

- Martin Luther King Jr. Federal Holiday Commission at the Federal Register

- Martin Luther King Jr. Day of Service official government site

- King Holiday and Service Act of 1994 Archived December 15, 2012, at the Wayback Machine at THOMAS

- Remarks on Signing the King Holiday and Service Act of 1994, President William J. Clinton, The American Presidency Project, August 23, 1994

- The King Center for Nonviolent Social Change

- N.H.'s Martin Luther King Jr. Day Didn't Happen Without A Fight