Mario José Molina Henríquez[a] (19 March 1943 – 7 October 2020)[7] was a Mexican physical chemist. He played a pivotal role in the discovery of the Antarctic ozone hole, and was a co-recipient of the 1995 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his role in discovering the threat to the Earth's ozone layer from chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) gases. He was the first Mexican-born scientist to receive a Nobel Prize in Chemistry and the third Mexican-born person to receive a Nobel prize.[8][9][10]

Mario Molina | |

|---|---|

Molina in 2011 | |

| Born | Mario José Molina Henríquez 19 March 1943 Mexico City, Mexico |

| Died | 7 October 2020 (aged 77) Mexico City, Mexico |

| Education | |

| Spouses |

|

| Awards | See list

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemistry |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | Vibrational Populations Through Chemical Laser Studies: Theoretical and Experimental Extensions of the Equal-gain Technique (1972) |

| Doctoral advisor | George C. Pimentel |

| Doctoral students | Renyi Zhang |

| Website | Official website |

| External audio | |

|---|---|

| |

In his career, Molina held research and teaching positions at University of California, Irvine, California Institute of Technology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, University of California, San Diego, and the Center for Atmospheric Sciences at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Molina was also Director of the Mario Molina Center for Energy and Environment in Mexico City. Molina was a climate policy advisor to the President of Mexico, Enrique Peña Nieto.[11]

Early life edit

Molina was born in Mexico City to Roberto Molina Pasquel and Leonor Henríquez. His father was a lawyer and diplomat who served as an ambassador to Ethiopia, Australia and the Philippines.[12] His mother was a family manager. With considerably different interests than his parents, Mario Molina went on to make one of the biggest discoveries in environmental science.

Mario Molina attended both elementary and primary school in Mexico.[13] However, before even attending high school, Mario Molina had developed a deep interest in chemistry. As a child he converted a bathroom in his home into his own little laboratory, using toy microscopes and chemistry sets. Ester Molina, Mario's aunt, and an already established chemist, nurtured his interests and aided him in completing more complex chemistry experiments.[12] At this time, Mario knew he wanted to pursue a career in chemistry, and at the age of 11, he was sent to a boarding school in Switzerland at Institut auf dem Rosenberg, where he learnt to speak German. Before this, Mario had initially wanted to become a professional violinist, but his love for chemistry triumphed over that interest.[13] At first Mario was disappointed when he arrived at the boarding school in Switzerland due to the fact that most of his classmates did not have the same interest in science as he did.[14]

Molina's early career consisted of research at various academic institutions. Molina went on to earn his bachelor's degree in chemical engineering at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) in 1965. Following this, Molina studied polymerization kinetics at the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg, West Germany,[13] for two years. Finally, he was accepted for graduate study at the University of California, Berkeley. After earning his doctorate he made his way to UC Irvine.[15] He then returned to Mexico where he kickstarted the first chemical engineering program at his alma mater. This was only the beginning of his chemistry endeavors.

Career edit

Mario Molina began his studies at the University of California at Berkeley in 1968, where he would obtain his PhD in physical chemistry. Throughout his years at Berkeley, he participated in various research projects such as the study of molecular dynamics using chemical lasers and investigation of the distribution of internal energy in the products of chemical and photochemical reactions.[13] Throughout this journey is where he worked with his professor and mentor George C. Pimentel who grew his love for chemistry even further.[13] After completing his PhD in physical chemistry, in 1973, he enrolled in a research program at UC Berkeley, with Sherwood Rowland. The topic of interest was Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) . The two would later on make one of the largest discoveries in atmospheric chemistry. They developed their theory of ozone depletion, which later influenced the mass public to reduce their use of CFCs. This kickstarted his career as a widely known chemist.

Between 1974 and 2004, Molina variously held research and teaching posts at University of California, Irvine, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at Caltech, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he held a joint appointment in the Department of Earth Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences and the Department of Chemistry.[5] On 1 July 2004, Molina joined the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at University of California, San Diego, and the Center for Atmospheric Sciences at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.[16] In addition he established a non-profit organization, which opened the Mario Molina Center for Strategic Studies in Energy and the Environment (Spanish: Centro Mario Molina para Estudios Estratégicos sobre Energía y Medio Ambiente) in Mexico City in 2005. Molina served as its director.[17]

Molina served on the board of trustees for Science Service, now known as Society for Science & the Public, from 2000 to 2005.[18] He also served on the board of directors of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation (2004–2014),[19] and as a member of the MacArthur Foundation's Institutional Policy Committee and its Committee on Global Security and Sustainability.[20]

Molina was nominated to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences as of 24 July 2000.[21] He served as a co-chair of the Vatican workshop and co-author of the report Well Under 2 Degrees Celsius: Fast Action Policies to Protect People and the Planet from Extreme Climate Change (2017) with Veerabhadran Ramanathan and Durwood Zaelke. The report proposed 12 scalable and practical solutions which are part of a three-lever cooling strategy to mitigate climate change.[22][23]

Molina was named by US president Barack Obama to form a transition team on environmental issues in 2008.[24] Under President Obama, he was a member of the United States President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology.[25]

Molina sat on the board of directors for Xyleco.[26]

He contributed to the content of the papal encyclical Laudato Si'.[27][28][29][30]

In 2020, Mario Molina contributed to research regarding the importance of wearing face masks amid the SARS-COV-2 pandemic. The research article titled "Identifying airborne transmission as the dominant route for the spread of COVID-19" was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America Journal in collaboration with Renyi Zhang, Yixin Li, Annie L. Zhang and Yuan Wang.[31]

Work on CFCs edit

Molina joined the lab of Professor F. Sherwood Rowland in 1973 as a postdoctoral fellow. Here, Molina continued Rowland's pioneering research into "hot atom" chemistry, which is the study of chemical properties of atoms with excess translational energy owing to radioactive processes.[32][33]

This study soon led to research into chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), apparently harmless gases that were used in refrigerants, aerosol sprays, and the making of plastic foams.[34] CFCs were being released by human activity and were known to be accumulating in the atmosphere. The basic scientific question Molina asked was "What is the consequence of society releasing something to the environment that wasn't there before?"[33]

Rowland and Molina had investigated compounds similar to CFCs before. Together they developed the CFC ozone depletion theory, by combining basic scientific knowledge about the chemistry of ozone, CFCs and atmospheric conditions with computer modelling. First Molina tried to figure out how CFCs could be decomposed. At lower levels of the atmosphere, they were inert. Molina realized that if CFCs released into the atmosphere do not decay by other processes, they will continually rise to higher altitudes. Higher in the atmosphere, different conditions apply. The highest levels of the stratosphere are exposed to the sun's ultraviolet light. A thin layer of ozone floating high in the stratosphere protects lower levels of the atmosphere from that type of radiation.[34]

Molina theorized that photons from ultraviolet light, known to break down oxygen molecules, could also break down CFCs, releasing a number of products including chlorine atoms into the stratosphere. Chlorine atoms (Cl) are radicals: they have an unpaired electron and are very reactive. Chlorine atoms react easily with ozone molecules (O3), removing one oxygen atom to leave O2 and chlorine monoxide (ClO).[34][35]

- Cl· + O

3 → ClO· + O

2

ClO is also a radical, which reacts with another ozone molecule to release two more O2 molecules and a Cl atom.

- ClO· + O

3 → Cl· + 2O

2

The radical Cl atom is not consumed by this pair of reactions, so it remains in the system.[34][35]

Molina and Rowland predicted that chlorine atoms, produced by this decomposition of CFCs, would act as an ongoing catalyst for the destruction of ozone. When they calculated the amounts involved, they realized that CFCs could start a seriously damaging chain reaction to the ozone layer in the stratosphere.[36][32][33]

In 1974, as a postdoctoral researcher at University of California, Irvine, Molina and F. Sherwood Rowland co-authored a paper in the journal Nature highlighting the threat of CFCs to the ozone layer in the stratosphere.[37] At the time, CFCs were widely used as chemical propellants and refrigerants. Molina and Rowland followed up the short Nature paper with a 150-page report for the United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), which they made available at the September 1974 meeting of the American Chemical Society in Atlantic City. This report and an ACS-organized press conference, in which they called for a complete ban on further releases of CFCs into the atmosphere, brought national attention.[38]

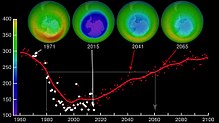

Rowland and Molina's findings were disputed by commercial manufacturers and chemical industry groups, and a public consensus on the need for action only began to emerge in 1976 with the publication of a review of the science by the National Academy of Sciences. Rowland and Molina's work was further supported by evidence of the long-term decrease in stratospheric ozone over Antarctica, published by Joseph C. Farman and his co-authors in Nature in 1985. Ongoing work led to the adoption of the Montreal Protocol (an agreement to cut CFC production and use) by 56 countries in 1987, and to further steps towards the worldwide elimination of CFCs from aerosol cans and refrigerators. By establishing this protocol, the amount of CFCs being emitted into the atmosphere decreased significantly, and while doing so, it has paced the rate of ozone depletion and even slowed climate change.[39][40] It is for this work that Molina later shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1995 with Paul J. Crutzen and F. Sherwood Rowland.[36] The citation specifically recognized him and his co-awardees for "their work in atmospheric chemistry, particularly concerning the formation and decomposition of ozone."[41]

Following this in 1985, after Joseph Farman discovered a hole in the ozone layer in Antarctica, Mario Molina led a research team to further investigate the cause of rapid ozone depletion in Antarctica. It was found that the stratospheric conditions in Antarctica were ideal for chlorine activation, which ultimately causes ozone depletion.[12]

Honors edit

Molina received numerous awards and honors,[5][6] including sharing the 1995 Nobel Prize in chemistry with Paul J. Crutzen and F. Sherwood Rowland for their discovery of the role of CFCs in ozone depletion.[1]

Molina was elected to the United States National Academy of Sciences in 1993.[42] He was elected to the United States Institute of Medicine in 1996,[43] and The National College of Mexico in 2003.[44] In 2007, he was elected to the American Philosophical Society.[45] He was also a member of the Mexican Academy of Sciences.[5] Molina was a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and co-chaired the 2014 AAAS Climate Science Panel, What We Know: The reality, risks and response to climate change.[46]

Molina won the 1987 Esselen Award of the Northeast section of the American Chemical Society, the 1988 Newcomb Cleveland Prize from the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the 1989 NASA Medal for Exceptional Scientific Advancement and the 1989 United Nations Environmental Programme Global 500 Award. In 1990, The Pew Charitable Trusts Scholars Program in Conservation and the Environment honored him as one of ten environmental scientists and awarded him a $150,000 grant.[5][47][48] In 1996, Molina received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement.[49] He received the 1998 Willard Gibbs Award from the Chicago Section of the American Chemical Society[50] and the 1998 American Chemical Society Prize for Creative Advances in Environment Technology and Science.[51] In 2003, Molina received the 9th Annual Heinz Award in the Environment.[52]

Asteroid 9680 Molina is named in his honor.[53]

On 8 August 2013, US president Barack Obama announced Molina as a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom,[54] saying in the press release:

Mario Molina is a visionary chemist and environmental scientist. Born in Mexico, Dr. Molina came to [The United States] to pursue his graduate degree. He later earned the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for discovering how chlorofluorocarbons deplete the ozone layer. Dr. Molina is a professor at the University of California, San Diego; Director of the Mario Molina Center for Energy and Environment; and a member of the President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology.[4] Molina was one of twenty-two Nobel Laureates who signed the third Humanist Manifesto in 2003.[55]

Mario Molina is the recipient of the Lifetime Achievement Award (Champions of the Earth) in 2014.[56]

On 19 March 2023, Molina was the subject of a Google Doodle in Mexico, the United States, Brazil, India, Germany, France, and other countries.[57]

Honorary degrees edit

Molina received more than thirty honorary degrees.[5]

- Yale University (1997)[58]

- Tufts University (2003)[59]

- Duke University (2009)[60]

- Harvard University (2012)[61]

- Mexican Federal Universities: National of Mexico (1996), Metropolitana (2004), Chapingo (2007), National Polytechnic (2009)

- Mexican State Universities: Hidalgo (2002),[62] State of Mexico (2006),[63] Michoacan (2009),[64] Guadalajara (2010),[65] San Luis Potosí (2011)[66]

- U.S. Universities: Miami (2001), Florida International (2002), Southern Florida (2005), Claremont Graduate (announced 2013)

- U.S. Colleges: Connecticut (1998), Trinity (2001), Washington (2011), Whittier (2012),[67] Williams (2015)

- Canadian Universities: Calgary (1997), Waterloo (2002), British Columbia (2011)

- European Universities: East Anglia (1996), Alfonso X (2009), Complutense of Madrid (2012), Free of Brussels (2010),

Personal life edit

Molina married fellow chemist Luisa Y. Tan in July 1973. They had met each other when Molina was pursuing his PhD at the University of California, Berkeley. They moved to Irvine, California in the fall of that year.[68] The couple divorced in 2005.[40] Luisa Tan Molina is now the lead scientist of the Molina Center for Strategic Studies in Energy and the Environment in La Jolla, California.[69] Their son, Felipe Jose Molina, was born in 1977.[13][70] Molina married his second wife, Guadalupe Álvarez, in February 2006.[13]

Molina died on 7 October 2020, aged 77, due to a heart attack.[71][40]

Works edit

- Molina, Luisa T., Molina, Mario J. and Renyi Zhang. "Laboratory Investigation of Organic Aerosol Formation from Aromatic Hydrocarbons", Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), United States Department of Energy, (August 2006).

- Molina, Luisa T., Molina, Mario J., et al. "Characterization of Fine Particulate Matter (PM) and Secondary PM Precursor Gases in the Mexico City Metropolitan Area", Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), United States Department of Energy, (October 2008).

Notes edit

- ^ In this Spanish name, the first or paternal surname is Molina-Pasquel and the second or maternal family name is Henríquez.

References edit

- ^ a b Massachusetts Institute of Technology (11 October 1995). "MIT's Mario Molina wins Nobel Prize in chemistry for discovery of ozone depletion". Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2008.

- ^ "The Heinz Awards, Mario Molina profile". Archived from the original on 22 October 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2009.

- ^ "Volvo Environment Prize". Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ a b "President Obama Names Presidential Medal of Freedom Recipients". Office of the Press Secretary, The White House. 8 August 2013. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Center for Oral History. "Mario J. Molina". Science History Institute. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ a b Caruso, David J.; Roberts, Jody A. (7 May 2013). Mario J. Molina, Transcript of an Interview Conducted by David J. Caruso and Jody A. Roberts at The Mario Molina Center, Mexico City, Mexico, on 6 and 7 May 2013 (PDF). Philadelphia, PA: Chemical Heritage Foundation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ^ "Mario Molina, Mexico chemistry Nobel winner, dies at 77". ABC News (USA). Associated Press. 7 October 2020. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ "Mario Molina, ganador del Premio Nobel 1995, muere a causa de un infarto". El Universal (in Spanish). 7 October 2020. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ^ García Hernández, Arturo (12 October 1995). "Ojalá que mi premio estimule la investigación en México". La Jornada (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 16 September 2009. Retrieved 29 September 2009.

Mario Molina, primer mexicano que obtiene el premio Nobel de Química...

- ^ "Mario Molina | Inside Science". Visionlearning. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ Davenport, Coral (27 May 2014). "Governments Await Obama's Move on Carbon to Gauge U.S. Climate Efforts". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ a b c "Mario Molina – Biography, Facts and Pictures". Archived from the original on 7 December 2022. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Molina, Mario (2007). "Autobiography". The Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1995". Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ "Mario Molina". Science History Institute. 1 June 2016. Archived from the original on 25 October 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ McDonald, Kim (5 February 2004). "Nobel Prize-Winning Chemist Joins UCSD Faculty". UCSD News. Archived from the original on 1 November 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ^ Denmark, Bonnie. "Mario Molina: Atmospheric Chemistry to Change Global Policy". VisionLearning. Archived from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ^ Zhang, Renyi (2016). "Mario J. Molina Symposium Atmospheric& Chemistry, Climate, and Policy". U.S. Department of Energy Office of Scientific and Technical Information. doi:10.2172/1333723. OSTI 1333723. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ "Past Board Members". MacArthur Foundation. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ "Board of Directors". MacArthur Foundation. Archived from the original on 25 October 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ "Mario José Molina". Pontifical Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on 27 October 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ "Vatican Pontifical Academy of Sciences Proposes Practical Solutions to Prevent Catastrophic Climate Change". Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development. 9 November 2017. Archived from the original on 25 October 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ "Vatican Pontifical Academy of Sciences to publish Well Under 2C: Ten Solutions for Carbon Neutrality & Climate Stability". Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development. 13 March 2018. Archived from the original on 25 October 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ Brown, Susan (9 August 2013). "Presidential Medal of Freedom to be Awarded to Two UC San Diego Professors". UC San Diego News Center. Archived from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ^ "PCAST Members". Office of Science and Technology Policy. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 25 October 2018 – via National Archives.

- ^ "Board of Directory". Xyleco. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ The Pontifical Academy of Sciences. "The Importance of the Encyclical Laudato si' in the Context of the Current Scientific Findings" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 April 2021. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ Léna, Pierre (17 October 2020). "A short text about Mario Molina". Archived from the original on 8 April 2021. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ Vera, Rodrigo (8 October 2020). "Mario Molina supo llevar sus creencias religiosas al ámbito científico". Archived from the original on 8 April 2021. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ "Murió Mario Molina, quien asesoró al Papa Francisco sobre medio ambiente". 7 October 2020. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ Zhang, Renyi; Li, Yixin; Zhang, Annie L.; Wang, Yuan; Molina, Mario J. (30 June 2020). "Identifying airborne transmission as the dominant route for the spread of COVID-19". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (26): 14857–14863. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11714857Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.2009637117. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 7334447. PMID 32527856.

- ^ a b (Nobel Lectures in Chemistry (1991–1995)). (1997). World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte.Ltd. River Edge, NJ. P 245-249.

- ^ a b c "Mario J. Molina, Ph.D. Biography and Interview". achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Mario Molina". Science History Institute. 12 December 2017. Archived from the original on 25 October 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ a b Holleman, Arnold Frederick; Aylett, Bernhard J.; Brewer, William; Eagleson, Mary; Wiberg, Egon (2001). Inorganic chemistry (1st English ed.). Academic Press. p. 462.

- ^ a b "Chlorofluorocarbons and Ozone Depletion: A National Historic Chemical Landmark". International Historic Chemical Landmarks. American Chemical Society. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ Mario Molina and FS Rowland (28 June 1974). "Stratospheric Sink for Chlorofluoromethanes: Chlorine Atom-Catalysed Destruction of Ozone". Nature. 249 (5460): 810–2. Bibcode:1974Natur.249..810M. doi:10.1038/249810a0. S2CID 32914300.

- ^ "This Week's Citation Classic: Rowland F S & Molina M J. Chiorofluoromethanes in the environment. Rev. Geophvs. Space Phys. 13: 1–35. 1975. Department of Chemistry. University of California. Irvine. CA" (PDF). Current Contents. 49: 12. 7 December 1987. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ^ "Has the Montreal Protocol been successful in reducing ozone-depleting gases in the atmosphere?" (PDF). NOAA Chemical Sciences Laboratory. 7 December 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 December 2022. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- ^ a b c Schwartz, John (13 October 2020). "Mario Molina, 77, Dies; Sounded an Alarm on the Ozone Layer". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1995". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 10 August 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ "Mario J. Molina". National Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ Silverman, Edward (25 November 1996). "Institute Of Medicine Increases Its Percentages Of Minority, Women Members In Latest Election". The Scientist. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ "Membros: Mario Molina". El Colegio Nacional. Archived from the original on 25 October 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Archived from the original on 18 June 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "What We Know: The reality, risks and response to climate change" (PDF). What We Know. AAAS. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 December 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ Oakes, Elizabeth. (2002). A to Z of Chemists. Facts on File Inc. New York City. P 143-145.

- ^ "Mario Molino". PEW. Archived from the original on 25 October 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement. Archived from the original on 15 December 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ "History of the Willard Gibbs Medal". Archived from the original on 23 July 2011.

- ^ "ACS Award in Environment". Archived from the original on 14 May 2014.

- ^ "Molina shares $250,000 Heinz Award". MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 21 February 2003. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ Jet Propulsion Laboratory Small-Body Database Browser. "9680 Molina (3557 P-L)". Archived from the original on 25 September 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- ^ Robbins, Gary (20 November 2013). "White House honors Molina, Ride". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ "Notable Signers". Humanism and Its Aspirations. American Humanist Association. Archived from the original on 5 October 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ^ Environment, U. N. (22 August 2019). "Mario José Molina-Pasquel Henríquez". Champions of the Earth. Archived from the original on 22 July 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ "Mario Molina's 80th Birthday". Archived from the original on 19 March 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ "Honorary degrees by Yale". Archived from the original on 21 May 2015.

- ^ "Honorary degrees by Tufts". Archived from the original on 23 May 2017. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- ^ "Honorary degrees granted by Duke in 2009". Archived from the original on 5 June 2014. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ "Honorary degrees granted by Harvard in 2012". Archived from the original on 18 January 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ "Honorary Doctorate by Universidad Autonoma del Estado de Hidalgo (spanish)". Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ^ "Honorary Doctorate by Universidad Autonoma del Estado de Mexico (spanish)" (PDF).[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Honorary Doctorate by Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolas de Hidalgo (spanish)". Archived from the original on 22 February 2014.

- ^ "Honorary Doctorate by Universidad de Guadalajara (spanish)". Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ^ "Honorary Doctorate by Universidad Autonoma de San Luis Potosi (spanish)". Archived from the original on 22 February 2014.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees | Whittier College". www.whittier.edu. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- ^ "Molina, Mario (1943– )". World of Earth Science. 2003. Archived from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Molina Center for Strategic Studies in Energy and the Environment". GuideStar. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ "Dr. Mario Molina". The Ozone Hole.com. Archived from the original on 3 October 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ^ "Fallece Mario Molina, Premio Nobel de Química 1995". El Financiero (in Spanish). 7 October 2020. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

External links edit

- Centro Mario Molina (in Spanish)

- Center for Oral History. "Mario J. Molina". Science History Institute.

- Caruso, David J.; Roberts, Jody A. (7 May 2013). Mario J. Molina, Transcript of an Interview Conducted by David J. Caruso and Jody A. Roberts at The Mario Molina Center, Mexico City, Mexico, on 6 and 7 May 2013 (PDF). Philadelphia, PA: Chemical Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- Mario Molina on Nobelprize.org including the Nobel Lecture on 8 December 1995 "Polar Ozone Depletion"

- Oral history interview with Mario J. Molina in Science History Institute Digital Collections