The Kalthoff repeater was a type of repeating firearm that was designed by members of the Kalthoff family around 1630,[1] and became the first repeating firearm to be brought into military service.[2] At least nineteen gunsmiths are known to have made weapons following the Kalthoff design.[2] Some early Kalthoff guns were wheellocks,[3][4] but the rest were flintlocks.[5] The capacity varied between 5 and 30 rounds, depending on the style of the magazines.[1] A single forward and back movement of the trigger guard, which could be done in 1–2 seconds, readied the weapon for firing.[6] The caliber of Kalthoff guns generally varied between 0.4–0.8 in (10–20 mm),[5] though 0.3 in (7.6 mm) caliber examples also exist.[7]

| Kalthoff repeater | |

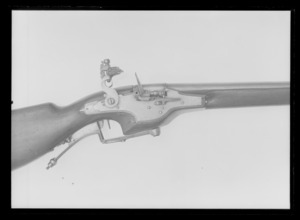

|---|---|

Kalthoff-type flintlock musket(1600s) at Livrustkammaren | |

| Place of origin | |

| Service history | |

| In service | c.1657–c.1696 |

| Used by | |

| Wars | |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Kalthoff gunsmiths |

| Designed | c. 1630 |

| Specifications | |

| Caliber | .40-.80 in |

| Barrels | Smoothbore |

| Action | Breech loading |

| Rate of fire | 30-60 rounds/min |

| Feed system | Separate component magazines, 5 to 30 rounds |

Origin and production edit

The Kalthoff system originates with a gun which was crafted in Solingen by an unknown member of the Kalthoff family around 1630.[1] Members of the family later moved to other areas of Europe, including Denmark, France, The Netherlands, England and Russia.[1] The first patent for the Kalthoff system was issued in France by Louis XIII to Guillaume Kalthoff in 1640.[1] This patent specified muskets and pistols that were capable of firing 8-10 shots with a single loading, while retaining the weight, length and handing of a standard firearm.[1][8] A year later in 1641, Peter Kalthoff obtained a Dutch patent for a rifle which could fire 29 rounds before reloading.[5][1][9] This patent did not specify the mechanism by which the gun worked, but mentioned that he would be able to perfect the design within a year.[1] Later that year, another Dutch patent was granted to an individual named Hendrick Bartmans.[1] This patent specified a gun with separate magazines for powder and ball, a 30 shot capacity, and a trigger guard that could be rotated to reload the weapon.[1] Bartmans made a magazine rifle following his patent around 1642, which likely used a snaplock, though it is now missing from the gun.[1] In 1645, Peter Kalthoff made a wheellock magazine rifle. This weapon is engraved with the text "Das Erste" (the first).[1] He made another repeating firearm in 1646, a wheellock which functioned in much the same way his previous weapon did. This weapon carries an inscription on the barrel just in front of the breech, which asserts a 30 round capacity.[4] That year he also made a repeating flintlock, which was given to the Danish Prince Frederik.[1] The weapon was constructed in Flensburg, and was the first flintlock weapon to be made in Germany.[10] Most repeaters made by Peter use a smooth, rounded trigger guard held in place by a rear trigger. Repeaters made by Matthias Kalthoff, who also worked in Denmark, have an initially straight trigger guard with a right angle formed by the carrier.[3] They do not have a release trigger, and use a straight rod for retention of the lever.[3] Guns by Matthias carry dates ranging from 1650 to 1679.[11]

In 1649, a pair of repeating pistols made by a gunsmith with the surname Kalthoff were reported to have been sent to King Frederik III.[1] Two pistols using the Kalthoff system are held at the National Museum of Denmark, but it can not be confirmed that these are the pistols mentioned.[1]

In Germany, wheellock repeaters were made by an individual referred to as the 'Master of Gottorp' (who was likely a gunsmith named Heinrich Habrecht).[14] Two wheellock magazine guns, made circa 1645 and 1650 respectively, are attributed to Habrecht.[14] These guns use a different breech system; the breech is quarter-cylindrical, and rotates at an axis parallel to the bore.[14] This breech had one or two chambers.[3] A later gun by Dutch gunmaker Alexander Hartingk, uses a similar breech.[3] This gun was made circa 1670 for Karl XI.[15] Hartingk's weapon uses a second powder magazine that sits to the right of the barrel, and primes the pan.[15]

A Kalthoff gun engraved with the year 1652 carries the name Cornelius Coster Utrecht.[1] This weapon has two ball magazines, one in the fore-stock and one in the butt (in addition to a powder magazine).[1] A cylindrical tube behind the breech block holds a strong coil spring, which pushes against the breech block.[1]

Caspar Kalthoff made a flintlock repeating gun in London between the years 1654 and 1665.[3] This gun used a rotating breech, and was later repaired by Ezekiel Baker in 1818.[16] An identical gun by Caspar also resides in the Tøjhusmuseet.[10] In 1658, Caspar made a repeating rifle that featured a sliding box-breech and had a capacity of 7 rounds.[17] Harman Barnes also made magazine guns in London, one of his guns used a rectangular sliding breech block with two chambers (and had a capacity of 5),[17] another used a cylinder breech system (and had a capacity of 6).[18] The latter gun was likely made around 1650, though it is unlikely it was completed before 1651.[19] This gun shares many features found on one of Hendrick Bartmans' guns.[19] It is possible the gun was simply imported from Holland and signed by Barnes, and was not crafted by him.[19] Kalthoff guns using cylindrical breeches were also made by Jan Flock of Utrecht, some of which he advertised for sale in 1668.[1] The price per weapon was at least 260 fl.[1]

Caspar Kalthoff the younger, the son of Caspar Kalthoff, made repeating weapons in Russia.[17] He arrived in Russia between 1664 and 1665, and made a repeating firearm there in 1665.[17]

Hans Boringholm, a pupil of Mathias Kalthoff, made repeating guns for hunting use.[5] Two repeating rifles attributed to Boringholm, dated 1670 and 1671, currently reside in the National Museum of Denmark.[20][21] Anders Mortensen, a pupil of Boringholm, also made repeating firearms.[5] On a Kalthoff gun signed By Mortensen, the powder passage is a separate component rather than being part of the lock.[3]

Around 1710, Charles Cousin made a gun using the Kalthoff system. This weapon had a capacity of 15, and was made in France.[22]

Mechanics and operation edit

There were two major variations of the Kalthoff repeater.[1] The first used a rectangular breech block with two or three chambers, a powder magazine in the stock, and had a capacity of up to 30 rounds.[1] At least one gun of this type also featured a coil spring behind the breech block which served to close the gap between it and the barrel.[1] The second variation used a vertical cylindrical breech block, stored powder beneath the lock, and had a capacity of up to 10 shots.[1] These guns had a removable cap over the breech, allowing the breech to be easily cleaned.[1] An additional variation of the Kalthoff used a cylindrical breech that rotated on an axis parallel to the bore.[6] The ball magazine was situated in a cylindrical cavity in the stock under the barrel.[6] Many Kalthoff guns used a magazine located in the ramrod cavity, and featured a cap designed to look like the end of the ramrod.[1] This style of magazine was around a 1 m (3 ft 3 in) in length and could hold over 60 14 mm (0.55 in) balls.[3] However, when fully loaded the balls amounted to about a 1 kg (2.2 lb) of weight, which changed the weapon's center of gravity.[3] Guns of the rectangular breech type had a flat spring that would bend to the right as the breech was moved, which held the balls in the magazine as the breech moved to the right.[1] Powder in the magazine could be reloaded through a hatch on the underside of the powder carrier if the powder magazine was located under the lock.[23][1] On Kalthoff guns with the magazine in the stock, the magazine was refilled through a hole covered by a sliding lid in the butt-plate, or through a hole uncovered by removing a screw on the left side-plate.[1] Some guns with a powder magazine in the butt also had a bolt inside the small of the stock, which could be turned to block the flow of powder.[1] The carrier on most guns contained enough powder (5ccs on one example)[23] for both the main charge and priming the pan.[6] Spring-loaded covers on the carrier and powder magazine ensured that powder could only flow when the carrier aligned with the magazine or powder passage.[5] The mechanism of many Kalthoff guns occupied the space normally reserved for a mainspring.[1] This had to be worked around by placing it in the stock and connecting it to the cock using a rod,[23][1] or by mounting it externally.[1]

With the muzzle facing upwards, laterally rotating the trigger guard approximately 155° to the right and back deposited a ball and load of powder in the breech and cocked the gun (or wound the wheel if the gun was a wheellock).[6][23] On some guns a small trigger had to be depressed before rotating the trigger guard.[24][10] A carrier attached to the trigger guard took the powder from the magazine to the breech, so there was no risk of an accidental ignition in the reserve.[6][25] The trigger guard was either coupled to the cylindrical breech by a cross-pin,[23] or moved the breech using a cogwheel.[5] When the lever was rotated forwards fully, the carrier aligned with a hole at the front of the lock plate. The powder could then flow through a tunnel in the lock plate, and into the breech.[23] The powder flowed directly through the breech into a cavity behind it in the case of cylinder breech guns, or into the middle chamber (or the rightmost one on two-hole variants) on rectangular breech guns.[1] In the case of cylindrical breech guns, as the lever was rotated back, a loading arm on the left side of the gun seated a ball in the breech in front of the powder.[23] On sliding breech block Kalthoff guns, a bullet would drop into the leftmost chamber as the gun was pointed upwards, and a plunger would seat the ball in the barrel as the left chamber aligned with the barrel.[5] Cylinder breech guns still held some powder in the breech tap as the lever was rotated back; this powder would flow into the priming pan just as the ball was inserted.[23] On rectangular breech guns, there would be remaining powder in the powder passage that would fall into the rightmost chamber as it shifted back towards the left, which then could flow into the pan.[1] Alternatively, if the breech had only two chambers the powder would flow directly from the passage into the pan.[1] Cocking the mechanism and closing the frizzen was achieved by a toothed bar that interfaced with a cogwheel attached to the lever.[1]

Use edit

In 1648, after Frederik III succeeded his father, he ordered that the Scanian Guard be equipped with Kalthoff repeaters.[5] This order was fulfilled by Peter and Mathias Kalthoff (and possibly a few other gunsmiths) and the guns were issued in 1657.[5] The Guards received about a hundred guns (some of the surviving guns are numbered via an engraving on the stock, 108 and 110 being the highest),[5] and they are thought to have been used in the Siege of Copenhagen[26](1658–59) and the Scanian War.[2][27] In 1659, during the Siege of Copenhagen, a royal bodyguard of Charles X was equipped with Kalthoff repeaters.[24][28] By 1696 the guns had been removed from service.[5] The Royal Armoury's inventory of 1775 still listed 133 repeating guns, by this time they were already regarded as antiques.[5]

Flaws edit

Despite having a remarkably fast fire rate for the time, the Kalthoff could never have become a standard military firearm because of its cost.[2] The mechanism had to be assembled with skill and care, and took far more time to assemble than an ordinary muzzle-loader.[2] Also, all the parts were interdependent; if a gear broke or jammed, the whole gun was unusable and only a specialist gunsmith could repair it.[2] It needed special care; powder fouling, or even powder that was slightly wet, could clog it.[2] Repeatedly firing the weapon created a buildup of powder fouling, making the lever increasingly hard to operate.[5] Since it was so expensive to buy and maintain, only wealthy individuals and elite soldiers could afford it.[2]

Derivatives edit

The Klett system edit

The Klett system was another system used for repeating firearms, and was an improvement on the Kalthoff system.[10] The oldest date found on guns using the system is 1652. Klett repeaters also use a horizontally rotating trigger guard to operate the weapon.[29] The Klett system features two rotating screw breeches, which function like the breech of the Ferguson Rifle. When the trigger guard is turned, the breeches descend and the rear cylinder collects powder from a magazine in the butt, and the front cylinder collects a ball from a magazine in the fore stock. A Klett carbine is described as firing "30 or 40 shots" in the memoirs of Prince Raimund Montecuccoli.[10]

Repeating rifle signed Michal Dorttlo, 1683 edit

A flintlock repeater, signed Michal Dorttlo 1683, uses many elements of the Kalthoff system. The breech is a vertically rotating cylinder, and the trigger guard can be rotated laterally to reload the weapon. However, it lacks the powder carrier found on Kalthoff guns, and instead houses both powder and ball in the butt. The gun uses a separate magazine for priming, but it is opened and closed manually.[1]

See also edit

Spencer repeating rifle: An American repeating rifle with a similar function.

References edit

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al Hoff, Arne. (1978). Dutch firearms. Stryker, Walter Albert, 1910-. London: Sotheby Parke Bernet. ISBN 0-85667-041-3. OCLC 4833404.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Peterson, Harold (1962). The Treasury of the Gun. New York: Crown Publishers Inc. p. 230.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Tøjhusmuseet (Denmark) (1951). Ældre dansk bøssemageri især i 1600-tallet. With summary and captions in English ... Thesis, etc. [By Arne Hoff.]. OCLC 559324918.

- ^ a b Hoff, Arne (1956). Royal Arms at Rosenborg. Chronol. Coll. of the Danish Kings at Rosenborg. OCLC 834973513.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Rausing, Gad (1991). "Kalthoff's Flintlocks..the Repeaters of 1657". Gun Digest 1991 45th Annual Edition: 62–64.

- ^ a b c d e f Peterson, Harold (1962). The Book of the Gun. Paul Hamlyn Publishing Group.

- ^ "8,1mm Magasinriffel med flintelås". Nationalmuseets Samlinger Online (in Danish). Retrieved 2020-08-19.

- ^ Waffenkunde, _, Verein Für Historische (1897). "Zeitschrift für historische Waffen- und Kostümkunde". Zeitschrift für historische Waffen- und Kostümkunde. doi:10.11588/DIGLIT.37713.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Georg, Lauber. "Kalthoff-Repetiersystem". Deutsches Waffen-Journal. September 1974: 940–941.

- ^ a b c d e Hayward, J. F. (John Forrest), 1916-1983. (1965). The art of the gunmaker. Barrie and Rockliff. OCLC 3652619.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ BOHEIM, WENDELIN. (2016). Meister der waffenschmiedekunst vom xiv. bis ins xviii. jahrhundert. HANSEBOOKS. ISBN 978-3-7428-4462-0. OCLC 1007047488.

- ^ Seitz, Heribert, 1904- (1946). Danica : en Bildsamling med text. Kungl. Livrustkammaren. OCLC 25017973.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "LSH | Flintlåsmagasingevär J Flock". emuseumplus.lsh.se. Retrieved 2020-07-24.

- ^ a b c Blackmore, Howard L. (1965). Guns and rifles of the world. London: Chancellor Press. ISBN 0-907486-01-0. OCLC 9447119.

- ^ a b "LSH | flintlåsmagasingevär Hartingk". emuseumplus.lsh.se. Retrieved 2020-08-21.

- ^ Blackmore, Howard L. (1968). Royal sporting guns at Windsor. Her Majesty's Stationery Office. p. 36. OCLC 837604998.

- ^ a b c d Britannia & Muscovy : English silver at the court of the Tsars. Dmitrieva, O. V. (Olʹga Vladimirovna), Abramova, N. Ė. (Natalii︠a︡ Ėduardovna), Yale Center for British Art., Gilbert Collection. New Haven, CT: Yale Center for British Art. 2006. ISBN 0-300-11678-0. OCLC 64230140.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Bonhams : An Exceptional 38-Bore Six-Shot Flintlock Breech-Loading Magazine Carbine On The Kalthoff Principle". www.bonhams.com. Retrieved 2020-07-02.

- ^ a b c Neal, W. Keith (William Keith) (1984). Great British gunmakers : 1540-1740. Back, D. H. L. (David Henry Lempriere). Norwich: Historical Firearms. ISBN 0-9508842-0-0. OCLC 12973229.

- ^ "11,3mm Magasinriffel med flintelås udført af Hans Boring Holm". Nationalmuseets Samlinger Online (in Danish). Retrieved 2020-07-10.

- ^ "12,3mm Magasinriffel med flintelås, med løb udført af Hans Boringholm". Nationalmuseets Samlinger Online (in Danish). Retrieved 2020-07-10.

- ^ "Hunting Magazine-fed Fifteen-shooter Gun (the Kalthoff System)". The State Hermitage Museum.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lugs, Jaroslav (1973). Firearms Past and Present. Bonhill Street London EC2A 4DA: Grenville Publishing Company Limited. pp. 165, 166. ISBN 9780903243056.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ a b Ellacott, S.E. (1955). Guns. London: Methuen Educational. pp. 24–25.

- ^ Blackmore, Howard L. (2000). Hunting weapons : from the Middle Ages to the twentieth century. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-40961-9. OCLC 247473483.

- ^ Isacson, Claes-Göran (2002). Karl X Gustavs krig: fälttågen i Polen, Tyskland, Baltikum, Danmark och Sverige 1655 - 1660 (in Swedish). Lund: Historiska Media. ISBN 978-91-89442-57-3.

- ^ Historie a vojenství. Magnet. 1954. p. 129.

- ^ Hoff, Arne (July 18, 1936). "Old Firearms in Which Technique Lagged Behind Invention". The Illustrated London News.

- ^ Grancsay, Stephen. "Cornel Klett, Hofbuchsenmacher". The Gun Digest. 9: 51.

- Harold L. Peterson The Book of the Gun Paul Hamlyn Publishing Group (1962)