Josiah Wedgwood FRS (12 July 1730 – 3 January 1795)[1] was an English potter, entrepreneur and abolitionist. Founding the Wedgwood company in 1759, he developed improved pottery bodies by systematic experimentation, and was the leader in the industrialisation of the manufacture of European pottery.[2]

Josiah Wedgwood | |

|---|---|

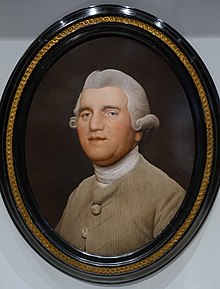

Josiah Wedgwood by George Stubbs, 1780, enamel on a Wedgwood ceramic tablet | |

| Born | 12 July 1730 Burslem, Staffordshire, England |

| Died | 3 January 1795 (aged 64) Etruria, Staffordshire, England |

| Resting place | Stoke Minster |

| Occupation(s) | Potter, entrepreneur |

The renewed classical enthusiasms of the late 1760s and early 1770s were of major importance to his sales promotion.[3] His expensive goods were in much demand from the upper classes, while he used emulation effects to market cheaper sets to the rest of society.[4] Every new invention that Wedgwood produced – green glaze, creamware, black basalt, and jasperware – was quickly copied.[5] Having once achieved efficiency in production, he obtained efficiencies in sales and distribution.[6] His showrooms in London gave the public the chance to see his complete range of tableware.[7]

Wedgwood's company never made porcelain during his lifetime, but specialised in fine earthenwares and stonewares that had many of the same qualities, but were considerably cheaper. He made great efforts to keep the designs of his wares in tune with current fashion. He was an early adopter of transfer printing which gave similar effects to hand-painting for a far lower cost. Meeting the demands of the consumer revolution that helped drive the Industrial Revolution in Britain, Wedgwood is credited as a pioneer of modern marketing.[8] He pioneered direct mail, money back guarantees, self-service, free delivery, buy one get one free, and illustrated catalogues.[9]

A prominent abolitionist fighting slavery, Wedgwood is remembered too for his Am I Not a Man And a Brother? anti-slavery medallion. He was a member of the Darwin–Wedgwood family, and he was the grandfather of Charles and Emma Darwin.

Early life edit

There were several related Wedgwood families in the village of Burslem, which around 1650 was the main centre of Staffordshire Potteries. Each pot-works had one bottle kiln. Thomas Wedgwood set up the Churchyard Works, near St John's parish church. In 1679 the business went to his son of the same name, master potter and churchwarden who bought a family pew, whose son Thomas, born in 1685, married Mary Stringer around 1710. She was the daughter of Josiah Stringer, a dissenting minister whose church had been outlawed by the Corporation Act, but preached occasionally. The young Thomas and Mary moved to a small pot-works producing moulded ware, then after his father died in 1716 they moved back to the Churchyard Works.[10][11] Their first son, Thomas, was born in 1717, Catherine was born in 1726, and Josiah was their thirteenth and last child.[12][13]

The children were baptised in the parish church; Josiah was baptised on 12 July 1730, probably his date of birth. Though her husband continued to occupy the pew, Mary brought them up with the values taught by her father,[14] who held that "knowledge based on reason, experience, and experiment was preferable to dogma."[15] Josiah went with the others to dame school then, around 1737 when able to walk to and from Newcastle-under-Lyme about 3 miles (4.8 km) distant, he went with them to the school there of Mr & Mrs Blunt who were reputably Puritans.[16]

After his father died in June 1739, Josiah finished school then, at about the usual age, began an informal apprenticeship and learnt to "throw" pots on the potter's wheel. When nearly twelve, he suffered a severe bout of smallpox which affected his right knee, but recovered sufficiently to get a formal indenture on 11 November 1744 to serve as an apprentice potter under his eldest brother Thomas who had taken over the Churchyard Works.[17][18] Josiah resumed potter's wheel work for a year or two, then knee pains came back so he did moulded ware and small ornaments. His brother thought his ideas of improvements unnecessary, and turned down his proposed partnership, so in 1751 or 1752 Josiah worked as a partner and manager in a pot-works near Stoke.[19]

Several potters locally used practical chemistry to innovate, and Wedgwood very soon went into partnership with Thomas Whieldon, who made high value small items such as snuff boxes. After six months of research and preparation, Wedgwood developed an exceptionally brilliant green glaze, and there was immediate demand for products with this glaze. Like his partner, Wedgwood occasionally took samples to Birmingham wholesalers to get orders, making business contacts. Unfortunately a knee injury spread to general inflammation, forcing him to convalesce in his room for several months. He took this as an opportunity to extend his education, reading literature and science books. His studies were helped by repeated visits from Wiliam Willet, minister of Newcastle-under-Lyme Meeting House, who had married Wedgwood's sister Catherine in 1754; "a man of extensive learning and general acquirements".[20] Josiah attended this English Presbyterian chapel, later known as Unitarian, and was a friend of Willet.[21][22]

Around 1759 Wedgwood expanded his Burslem business, renting Ivy House Works and cottage from his distant cousins John and Thomas. They were often visited by their brother Richard Wedgwood, a wealthy Congleton cheesemonger, along with his daughter Sarah. She had been well educated, as was Unitarian practice, soon "Jos" wrote to his "loving Sally".[23][24]

On a business trip in 1762, Wedgwood had another knee accident. After attention from a surgeon, he was accommodated by Thomas Bentley, who would become his close business associate. While recuperating, he met the chemist Joseph Priestley, who became a close friend, and discussed his dissenting theological ideas. In May Wedgwood began a long correspondence with Bentley, writing from Burslem, and moved into larger premises, the Brick House Works and dwelling.[25][26]

Marriage and children edit

Wedgwood had wooed his distant cousin Sarah (1734–1815) since first meeting her, but her father Richard wanted to ensure his prospective son in law had sufficient means, and insisted on long negotiation by attorneys over the marriage settlement. Then, "Jos" and "Sally" were married on 25 January 1764 at Astbury parish church, near Congleton.[27][28] They had eight children:

- Susannah Wedgwood (3 January 1765 – 1817), known to the family as "Sukey", married Robert Darwin and became the mother of the English naturalist Charles Darwin. Charles married Emma Wedgwood, his cousin.

- John Wedgwood (1766–1844), joined the business rather reluctantly, mainly interested in horticulture

- Richard Wedgwood (1767–1768) (died as a child)

During negotiations for the proposed Trent and Mersey Canal, Wedgwood met and befriended Erasmus Darwin (Robert's father), whose family long remembered as saying that Unitarianism was "a feather-bed to catch a falling Christian".

After more problems with his knee, Wedgwood had his leg amputated on 28 May 1768.[29][30]

- Josiah Wedgwood II (1769–1843) (father of Emma Darwin, cousin and wife of Charles Darwin)

The Etruria Works built at the canal opened in June 1769, in July the family moved there. For several months they stayed in Little Etruria, a house built for Bentley's use, then they moved into the just competed Etruria Hall.[31]

- Thomas Wedgwood (1771–1805) (no children), best known as a pioneer photographer

- Catherine Wedgwood (1774–1823) (no children)

- Sarah Wedgwood (1776–1856) (no children, very active in the abolition movement and founding member of Birmingham Ladies Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves, the first anti-slavery society for women)[32]

- Mary Anne Wedgwood (1778–86) (died as a child)

As a Unitarian,[33] aware of legal constraints on nonconformists getting education, Wedgwood supported dissenting academies such as Warrington Academy, where he gave lectures on chemistry,[34] and was made a professor of metallurgy.[35] The older children first went to school in 1772; the boys to Hindley, while Sukey went to a dame school in Lancashire along with his niece, the daughter of Mrs. Willet.[36] In 1774 he sent his son John to the Bolton boarding school trun by the Unitarian minister Philip Holland, followed by young Josiah the next year, and Tom in 1779.[37]

Career and work edit

Pottery edit

Wedgwood was keenly interested in the scientific advances of his day and it was this interest that underpinned his adoption of its approach and methods to revolutionise the quality of his pottery. His unique glazes began to distinguish his wares from anything else on the market.

By 1763, he was receiving orders from the highest-ranking people, including Queen Charlotte. Wedgwood convinced her to let him name the line of pottery she had purchased "Queen's Ware", and trumpeted the royal association in his paperwork and stationery. Anything Wedgwood made for the Queen was automatically exhibited before it was delivered.[38] In 1764, he received his first order from abroad. Wedgwood marketed his Queen's Ware at affordable prices, everywhere in the world British trading ships sailed. In 1767 he wrote, "The demand for this sd. Creamcolour, Alias, Queen Ware, Alias, Ivory, still increases – It is amazing how rapidly the use of it has spread all most [sic] over the whole Globe."[26]

He first opened a warehouse at Charles Street, Mayfair in London as early as 1765 and it soon became an integral part of his sales organization. In two years, his trade had outgrown his rooms in Grosvenor Square.[39] In 1767, Wedgwood and Bentley drew up an agreement to divide decorative wares between them, the domestic wares being sold on Wedgwood's behalf.[40] A special display room was built to beguile the fashionable company. Wedgwood's in fact had become one of the most fashionable meeting places in London. His workers had to work day and night to satisfy the demand, and the crowds of visitors showed no sign of abating.[41] The proliferating decoration, the exuberant colours, and the universal gilding of rococo were banished, the splendours of baroque became distasteful; the intricacies of chinoiserie lost their favour. The demand was for purity, simplicity and antiquity.[42] To encourage this outward spread of fashion and to speed it on its way Wedgwood set up warehouses and showrooms at Bath, Liverpool and Dublin in addition to his showrooms at Etruria and in Westminster.[43] Great care was taken in timing the openings, and new goods were held back to increase their effect.[38]

The most important of Wedgwood's early achievements in vase production was the perfection of the black stoneware body, which he called "basalt". This body could imitate the colour and shapes of Etruscan or Greek vases which were being excavated in Italy. In 1769, "vases was all the cry" in London; he opened a new factory called Etruria, north of Stoke. Wedgwood became what he wished to be: "Vase Maker General to the Universe".[44] Around 1771, he started to experiment with Jasperware, but he did not advertise this new product for a couple of years.

Sir George Strickland, 6th Baronet, was asked for advice on getting models from Rome.[45] Gilding was to prove unpopular, and around 1772, Wedgwood reduced the amount of "offensive gilding" in response to suggestions from Sir William Hamilton.[46] When English society found the uncompromisingly naked figure of the classics "too warm" for their taste, and the ardor of the Greek gods too readily apparent, Wedgwood was quick to cloak their pagan immodesty – gowns for the girls and fig leaves for the gods were usually sufficient.[47] Just as he felt that his flowerpots would sell more if they were called "Duchess of Devonshire flowerpots", his creamware more if called Queensware, so he longed for Brown, James Wyatt, and the brothers Adam to lead the architect in the use of his chimneypieces and for George Stubbs to lead the way in the use of Wedgwood plaques.

Wedgwood hoped to monopolise the aristocratic market and thus win for his wares a special social cachet that would filter to all classes of society. Wedgwood fully realised the value of such a lead and made the most of it by giving his pottery the name of its patron: Queensware, Royal Pattern, Russian pattern, Bedford, Oxford and Chetwynd vases for instance. Whether they owned the original or merely possessed a Wedgwood copy mattered little to Wedgwood's customers.[48] In 1773 they published the first Ornamental Catalogue, an illustrated catalogue of shapes.[40] A plaque, in Wedgwood's blue pottery style, marking the site of his London showrooms between 1774 and 1795 in Wedgwood Mews, is located at 12, Greek Street, London, W1.[49]

In 1773, Empress Catherine the Great ordered the (Green) Frog Service from Wedgwood, consisting of 952 pieces and over a thousand original paintings, for the Kekerekeksinen Palace (palace on a frog swamp (in Finnish)), later known as Chesme Palace. Most of the painting was carried out in Wedgwood's decorating studio at Chelsea.[50] Its display, Wedgwood thought, 'would bring an immence [sic] number of People of Fashion into our Rooms. For over a month the fashionable world thronged the rooms and blocked the streets with their carriages.[51] (Catharine paid £2,700. It can still be seen in the Hermitage Museum.[52]) Strictly uneconomical in themselves, these productions offered huge advertising value.[53]

Later years edit

As a leading industrialist, Wedgwood was a major backer of the Trent and Mersey Canal dug between the River Trent and River Mersey, during which time he became friends with Erasmus Darwin. Later that decade, his burgeoning business caused him to move from the smaller Ivy Works to the newly built Etruria Works, which would run for 180 years. The factory was named after the Etruria district of Italy, where black porcelain dating to Etruscan times was being excavated. Wedgwood found this porcelain inspiring, and his first major commercial success was its duplication with what he called "Black Basalt". He combined experiments in his art and in the technique of mass production with an interest in improved roads, canals, schools, and living conditions. At Etruria, he even built a village for his workers. The motto, Sic fortis Etruria crevit, was inscribed over the main entrance to the works.[54]

Not long after the new works opened, continuing trouble with his smallpox-afflicted knee made necessary the amputation of his right leg. In 1780, his long-time business partner Thomas Bentley died, and Wedgwood turned to Darwin for help in running the business. As a result of the close association that grew up between the Wedgwood and Darwin families, Josiah's eldest daughter would later marry Erasmus' son.

To clinch his position as leader of the new fashion, he sought out the famous Barberini vase as the final test of his technical skill.[42] Wedgwood's obsession was to duplicate the Portland Vase, a blue-and-white glass vase dating to the first century BC. He worked on the project for three years, eventually producing what he considered a satisfactory copy in 1789.

In 1784, Wedgwood was exporting nearly 80% of his total produce. By 1790, he had sold his wares in every city in Europe.[55] To give his customers a greater feeling of the rarity of his goods, he strictly limited the number of jaspers on display in his rooms at any given time.

He was elected to the Royal Society in 1783 for the development of the pyrometric device (a type of pyrometer) working on the principle of clay contraction (see Wedgwood scale for details) to measure the high temperatures which are reached in kilns during the firing of ceramics.[56][57]

He was an active member of the Lunar Society of Birmingham, often held at Erasmus Darwin House, and is remembered on the Moonstones in Birmingham.

Death edit

After passing on his company to his sons, Wedgwood died at home, probably of cancer of the jaw, in 1795. He was buried three days later in the parish church of Stoke-upon-Trent.[58] Seven years later a marble memorial tablet commissioned by his sons was installed there.[59]

Legacy and influence edit

"[Wedgwood] is someone who commercialised creativity. He made an industry of his talent."

— Sir Howard Stringer, chairman of Sony Corporation, 2012.[60]

One of the wealthiest entrepreneurs of the 18th century, Wedgwood created goods to meet the demands of the consumer revolution and growth in prosperity that helped drive the Industrial Revolution in Britain.[8] He is credited as a pioneer of modern marketing, specifically direct mail, money back guarantees, travelling salesmen, carrying pattern boxes for display, self-service, free delivery, buy one get one free, and illustrated catalogues.[9] Wedgwood is also noted as an early adopter/founder of managerial accounting principles in Anthony Hopwood's "Archaeology of Accounting Systems." Historian Tristram Hunt called Wedgwood a "difficult, brilliant, creative entrepreneur whose personal drive and extraordinary gifts changed the way we work and live."[61]

He was a friend, and commercial rival, of the potter John Turner the elder; their works have sometimes been misattributed.[62][63] For the further comfort of his foreign buyers he employed French-, German-, Italian- and Dutch-speaking clerks and answered their letters in their native tongue.[64]

Wedgwood belonged to the fifth generation of a family of potters whose traditional occupation continued through another five generations. Wedgwood's company is still a famous name in pottery (as part of the Fiskars group), and "Wedgwood China" is sometimes used as a term for his Jasperware, the coloured pottery with applied relief decoration (usually white).[61]

Abolitionism edit

Wedgwood was a prominent slavery abolitionist. His friendship with Thomas Clarkson – abolitionist campaigner and the first historian of the British abolition movement – aroused his interest in slavery. Wedgwood mass-produced cameos depicting the seal for the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade and had them widely distributed, which thereby became a popular and celebrated image. The Wedgwood anti-slavery medallion was the most famous image of a black person in all of 18th-century art.[65] The actual design of the cameo was probably done by either William Hackwood or Henry Webber who were modellers at his factory.[66]

From 1787 until his death in 1795, Wedgwood actively participated in the abolition-of-slavery cause. His Slave Medallion brought public attention to abolition.[67] Wedgwood reproduced the design in a cameo with the black figure against a white background and donated hundreds to the society for distribution. Thomas Clarkson wrote: "ladies wore them in bracelets, and others had them fitted up in an ornamental manner as pins for their hair. At length the taste for wearing them became general, and thus fashion, which usually confines itself to worthless things, was seen for once in the honourable office of promoting the cause of justice, humanity and freedom".[68]

The design on the medallion became popular and was used elsewhere: large-scale copies were painted to hang on walls[69] and it was used on clay tobacco pipes.[70]

Other edit

- Erasmus Darwin House, Erasmus Darwin Museum house and gardens

- A locomotive named "Josiah Wedgwood" ran on the Cheddleton Railway Centre in 1977. It returned in May 2016 following ten years away.[71]

- Commemorating the landing of the First Fleet at Sydney Cove in January 1788, Wedgwood made the Sydney Cove Medallion, using a sample of clay from the cove from Sir Joseph Banks, who had himself received it from Governor Arthur Phillip. Wedgwood made the commemorative medallion showing an allegorical group described as, "Hope encouraging Art and Labour, under the influence of Peace, to pursue the employments necessary to give security and happiness to an infant settlement".[72]

Notes edit

- ^ Church, Arthur Herbert (1899). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 60. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ Ashton, T. S. (1948). The Industrial Revolution 1760–1830, p. 81

- ^ McKendrick 1982, p. 113

- ^ McKendrick 1982, p. 105.

- ^ McKendrick 1982, p. 107.

- ^ McKendrick 1982, p. 108.

- ^ Rendell, Mike (2015). "The Georgians in 100 Facts". p. 40. Amberley Publishing Limited

- ^ a b "Why the Industrial Revolution Happened Here". BBC. 11 January 2017.

- ^ a b "They Broke It". The New York Times. 9 January 2009.

- ^ Meteyard 1865, pp. 188–190, 192–193, 199–202.

- ^ Gordon, A. (1917). Freedom After Ejection: A Review (1690-1692) of Presbyterian and Congregational Nonconformity in England and Wales. Historical series. University Press. p. 361. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ Freeman 2007, pp. 292, 298–299.

- ^ Jewitt 1865, p. 85.

- ^ Meteyard 1865, pp. 202, 204.

- ^ Harris, M.W. (2018). Historical Dictionary of Unitarian Universalism. Historical Dictionaries of Religions, Philosophies, and Movements Series. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 584. ISBN 978-1-5381-1591-6. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ Meteyard 1865, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Meteyard 1865, pp. 217–222.

- ^ Meyer, Michal (2018). "Old Friends". Distillations. 4 (1). Science History Institute: 6–9. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ^ Meteyard 1865, pp. 228–234.

- ^ Meteyard 1865, pp. 236–240, 246–248.

- ^ Jewitt 1865, p. 421.

- ^ "Newcastle-under-Lyme Unitarian Meeting House History". Newcastle-under-Lyme Unitarians. Retrieved 7 January 2024. – Historical events

- ^ Meteyard 1865, pp. 251–252, 279, 282–283, 300.

- ^ Healey 2010, p. 12.

- ^ Meteyard 1865, pp. 299–301, 308–309, 329–331.

- ^ a b Thomson, Gary (November 1995). "Josiah Wedgwood. (cover story)". Antiques & Collecting Magazine.

- ^ Meteyard 1865, pp. 300, 332–334.

- ^ Healey 2010, p. 14.

- ^ Healey 2010, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Darwin, C. R. (1879), Preliminary notice. In Ernst Krause, Erasmus Darwin. Translated from the German by W. S. Dallas, with a preliminary notice by Charles Darwin. London: John Murray, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Healey 2010, pp. 16, 21, 24.

- ^ Midgley, Clare (1992). Women Against Slavery. New York: Routledge. p. 56. ISBN 0-203-64531-6.

- ^ Meteyard 1871, p. 6.

- ^ Healey 2010, pp. 24–27.

- ^ Meteyard 1871, p. 9.

- ^ Meteyard 1866, pp. 267–268.

- ^ Meteyard 1871, pp. 9–10.

- ^ a b McKendrick 1982, p. 121.

- ^ McKendrick 1982, p. 118.

- ^ a b Coutts, Howard. The Art of Ceramics. European Ceramic Design 1500–1830, p. 180.

- ^ McKendrick 1982, p. 119.

- ^ a b McKendrick 1982, p. 114.

- ^ McKendrick 1982, p. 120.

- ^ McKendrick 1982, p. 140.

- ^ McKendrick 1982, p. 110-111.

- ^ The Art of Ceramics. European Ceramic Design 1500–1830, Howard Coutts, p. 181.

- ^ McKendrick 1982, p. 113.

- ^ McKendrick 1982, p. 112.

- ^ "Plaque: Josiah Wedgwood". londonremembers.com. 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- ^ The Art of Ceramics. European Ceramic Design 1500–1830 by Howard Coutts, p. 185.

- ^ McKendrick 1982, p. 122.

- ^ Pieces from the Green Frog Service. Josiah Wedgwood (1773–1774) Archived 22 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Hermitage Museum

- ^ McKendrick 1982, p. 110.

- ^ “Historic Link with Josiah Wedgwood”, Belfast Newsletter, 24 May 1935, p.6.

- ^ McKendrick 1982, pp. 134–135.

- ^ "BBC – History – Historic Figures: Josiah Wedgwood (1730–1795)". bbc.co.uk.

- ^ Science Museum; Galileo Museum

- ^ "History & Heritage". stokeminster.org/. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- ^ "Wedgwood memorial tablet". Retrieved 27 March 2022

- ^ "Creative sector seeks to create wider support". BBC. 14 January 2017.

- ^ a b Hunt, Tristram (2021). The Radical Potter: The Life and Times of Josiah Wedgwood. Henry Holt and Company.

- ^ "John Turner". thepotteries.org. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ "New Hall Works, Shelton". thepotteries.org. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ McKendrick 1982, p. 134.

- ^ "British History – Abolition of the Slave Trade 1807". BBC. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

The Wedgwood medallion was the most famous image of a black person in all of 18th-century art.

- ^ "Am I Not a Man and a Brother?", 1787

- ^ Did you know? – Josiah WEDGWOOD was a keen advocate of the slavery abolition movement. Thepotteries.org. Retrieved on 2 January 2011.

- ^ "Wedgwood". Archived from the original on 8 July 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

Thomas Clarkson wrote; ladies wore them in bracelets, and others had them fitted up in an ornamental manner as pins for their hair. At length the taste for wearing them became general, and thus fashion, which usually confines itself to worthless things, was seen for once in the honourable office of promoting the cause of justice, humanity and freedom.

- ^ Scotland and the Slave Trade: 2007 Bicentenary of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act Archived 7 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine, The Scottish Government, 23 March 2007

- ^ A History of the World – Object : anti-slavery tobacco pipe. BBC. Retrieved on 2 January 2011.

- ^ "A brief history of the CVR php". hurnet-valley-railway.co.uk. Archived from the original on 10 July 2010. Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- ^ "National Museum of Australia". nma.gov.au.; Robert J. King, "'Etruria': the Great Seal of New South Wales", Journal of the Numismatic Association of Australia, vol.5, October 1990, pp.3–8. [1] Archived 29 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine; photo of example

References edit

- Dolan, Brian (2004). Wedgwood: The First Tycoon. Viking Adult. ISBN 0-670-03346-4

- Freeman, R. B. (2007), Charles Darwin: A companion (2d online ed.), The Complete Works of Charles Darwin Online, retrieved 18 June 2008

- Healey, E. (2010). Emma Darwin: The Wife of an Inspirational Genius. Headline. ISBN 978-0-7553-6160-1. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- Jewitt, L.F.W. (1865). The Wedgwoods: Being a Life of Josiah Wedgwood; with Notices of His Works and Their Productions, Memoirs of the Wedgewood and Other Families, and a History of the Early Potteries of Staffordshire. Virtue Brothers and Company. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- McKendrick, Neil. "Josiah Wedgwood and the Commercialization of the Potteries", in: McKendrick, Neil; Brewer, John & Plumb, J.H. (1982), The Birth of a Consumer Society: The commercialization of Eighteenth-century England

- Meteyard, Eliza (1865). The Life of Josiah Wedgwood: From His Private Correspondence and Family Papers ... with an Introductory Sketch of the Art of Pottery in England. Vol. 1. Hurst and Blackett. Retrieved 4 January 2024.

- Meteyard, Eliza (1866). The Life of Josiah Wedgwood: From His Private Correspondence and Family Papers ... with an Introductory Sketch of the Art of Pottery in England. Vol. 2. Hurst and Blackett. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- Meteyard, Eliza (1871). A Group of Englishmen ...: Being Records of the Younger Wedgwoods and Their Friends; Embracing the History of the Discovery of Photography. Longmans, Green, and Company. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

Further reading edit

- Hunt, Tristram. The Radical Potter: Josiah Wedgwood and the Transformation of Britain (2021)

- Burton, Anthony. Josiah Wedgwood: A New Biography (2020)

- Koehn, Nancy F. Brand New : How Entrepreneurs Earned Consumers' Trust from Wedgwood to Dell (2001) pp. 11–42.

- Langton, John. "The ecological theory of bureaucracy: The case of Josiah Wedgwood and the British pottery industry." Administrative Science Quarterly (1984): 330–354.

- McKendrick, Neil. "Josiah Wedgwood and Factory Discipline." Historical Journal 4.1 (1961): 30–55. online

- McKendrick, Neil. "Josiah Wedgwood and cost accounting in the Industrial Revolution." Economic History Review 23.1 (1970): 45–67. online

- McKendrick, Neil. "Josiah Wedgwood: an eighteenth-century entrepreneur in salesmanship and marketing techniques." Economic History Review 12.3 (1960): 408–433. online

- Meteyard, Eliza. Life and Works of Wedgwood (2 vol 1865) vol 1 online; also vol 2 online

- Reilly, Robin, Josiah Wedgwood 1730–1795 (1992), scholarly biography

- Wedgwood, Julia, and Charles Harold Herford. The Personal Life of Josiah Wedgwood, the Potter (1915) online

- Young, Hilary (ed.), The Genius of Wedgwood (exhibition catalogue), 1995, Victoria and Albert Museum, ISBN 185177159X

External links edit

- Wedgwood website Archived 5 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Vaizey, Marina, "Science into Art, Art into Science", The Tretyakov Gallery Magazine, No 2, 2016 (51) (good online summary)

- Wedgwood collection at the Lady Lever Art Gallery

- Wedgwood Museum

- The Great Crash by Jenny Uglow, The Guardian, 7 February 2009

- National Museum of Australia Archived 17 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine The Sydney Cove Medallion (Flash required for close-up viewing).

- The Story of Wedgwood Archived 3 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Josiah Wedgwood Correspondence (transcripts), John Rylands Library, Manchester.