Jewish emancipation was the process in various nations in Europe of eliminating Jewish disabilities, e.g. Jewish quotas, to which European Jews were then subject, and the recognition of Jews as entitled to equality and citizenship rights.[1] It included efforts within the community to integrate into their societies as citizens. It occurred gradually between the late 18th century and the early 20th century.

Jewish emancipation followed after the Age of Enlightenment and the concurrent Haskalah, or Jewish Enlightenment.[2] Various nations repealed or superseded previous discriminatory laws applied specifically against Jews where they resided. Before the emancipation, most Jews were isolated in residential areas from the rest of the society; emancipation was a major goal of European Jews of that time, who worked within their communities to achieve integration in the majority societies and broader education. Many became active politically and culturally within wider European civil society as Jews gained full citizenship. They emigrated to countries offering better social and economic opportunities, such as the United Kingdom and the Americas. Some European Jews turned to socialism,[3] Zionism[4] or both.[5]

Background edit

Jews were subject to a wide range of restrictions throughout most of European history. Since the Fourth Council of the Lateran in 1215, Christian Europeans required Jews and Muslims to wear special clothing, such as the Judenhut and the yellow badge for Jews, to distinguish them from Christians. The practice of their religions was often restricted, and they had to swear special oaths. Jews were not allowed to vote, where voting existed, and some countries formally prohibited their entry, such as Norway, Sweden and Spain after the expulsion in the late 15th century.

Jewish involvement in gentile society began during the Age of Enlightenment. Haskalah, the Jewish movement supporting the adoption of enlightenment values, advocated an expansion of Jewish rights within European society. Haskalah followers advocated "coming out of the ghetto", not just physically but also mentally and spiritually.

In 1790, in the United States, President George Washington wrote a letter establishing that Jews in America would share full equal rights, including the right to practice their religion, with all other Americans.[6] However, Jewish commentators observed that exclusion of Jewish citizens from political office occurred in a number of areas still in 1845.[7] In fact, American Jewish citizens organized for political rights in the 1800s, and then for further civil rights in the 1900s.[8]

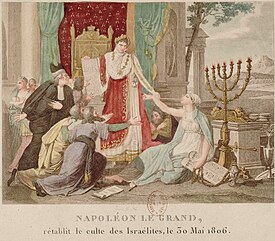

On September 28, 1791, revolutionary France emancipated its Jewish population. The 40,000 Jews living in France at the time were the first to confront the opportunities and challenges offered by emancipation. The civic equality that the French Jews attained became a model for other European Jews.[9] Newfound opportunities began to be provided to the Jewish people, and they slowly pushed toward equality in other parts of the world. In 1796 and 1834, the Netherlands granted the Jews equal rights with non-Jews.[10][11] Napoleon freed the Jews in areas he conquered in Europe outside France (see Napoleon and the Jews). Greece granted equal rights to Jews in 1830. But, it was not until the revolutions of the mid-19th century that Jewish political movements would begin to persuade governments in Great Britain and Central and Eastern Europe to grant equal rights to Jews.[12]

In English law and some successor legal systems there was a convention known as benefit of clergy (Law Latin: privilegium clericale) by which an individual convicted of a crime, through claiming to be a Christian clergyman (usually as a pretext; in most cases the defendant claiming benefit of clergy was a layperson) could escape punishment or receive a reduced punishment. In the opinions of many contemporary legal scholars, this meant that a Jew who had not renounced Judaism could not claim benefit of clergy.[13] In England itself the practice of granting benefit of clergy was ended in 1827 but it continued further in other jurisdictions.

Emancipation movements edit

The early stages of Jewish emancipation movements were part of the general progressive efforts to achieve freedom and rights for minorities. While this was a movement, it was also a pursuit for equal rights.[14] Thus, the emancipation movement would be a long process. The question of equal rights for Jews was tied to demands for constitutions and civil rights in various nations. Jewish statesmen and intellectuals, such as Heinrich Heine, Johann Jacoby, Gabriel Riesser, Berr Isaac Berr, and Lionel Nathan Rothschild, worked with the general movement toward liberty and political freedom, rather than for Jews specifically.[15]

In 1781, the Prussian civil servant Christian Wilhelm Dohm published the famous script Über die bürgerliche Emanzipation der Juden. Dohm disproves the antisemitic stereotypes and pleads for equal rights for Jews. To this day, it is called the Bible of Jewish emancipation.[16]

In the face of persistent anti-Jewish incidents and blood libels, such as the Damascus affair of 1840, and the failure of many states to emancipate the Jews, Jewish organizations formed to push for the emancipation and protection of their people. The Board of Deputies of British Jews under Moses Montefiore, the Central Consistory in Paris, and the Alliance Israelite Universelle all began working to assure the freedom of Jews.

Jewish emancipation, implemented under Napoleonic rule in French occupied and annexed states, suffered a setback in many member states of the German Confederation following the decisions of the Congress of Vienna. In the final revision of the Congress on the rights of the Jews, the emissary of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen, Johann Smidt – unauthorised and unconsented to by the other parties – altered the text from "The confessors of Jewish faith are preserved the rights already conceded to them in the confederal states", by replacing a single word, which entailed serious consequences, into: "The confessors of Jewish faith are preserved the rights already conceded to them by the confederal states."[17] A number of German states used the altered text version as legal grounds to reverse the Napoleonic emancipation of Jewish citizens. The Prussian emissary Wilhelm von Humboldt and the Austrian Klemens von Metternich promoted the preservation of Jewish emancipation, as maintained by their own countries, but were not successful in others.[15]

During the Revolutions of 1848, Jewish emancipation was granted by the Basic Rights of the Frankfurt Parliament (Paragraph 13), which said that civil rights were not to be conditional on religious faith. But only some German states introduced the Frankfurt parliamentary decision as state law, such as Hamburg; other states were reluctant. Important German states, such as Prussia (1812), Württemberg (1828), Electorate of Hesse (1833), and Hanover (1842), had already emancipated their Jews as citizens. By doing so, they hoped to educate the gentiles, and terminate laws that sought to oppress the Jews.[18] Although the movement was mostly successful; some early emancipated Jewish communities continued to suffer persisting or new de facto, though not legal, discrimination against those Jews trying to achieve careers in public service and education. Those few states that had refrained from Jewish emancipation were forced to do so by an act of the North German Federation on 3 July 1869, or when they acceded to the newly united Germany in 1871. The emancipation of all Jewish Germans was reversed by Nazi Germany from 1933 until the end of World War II.[12]

Dates of emancipation edit

In some countries, emancipation came with a single act. In others, limited rights were granted first in the hope of "changing" the Jews "for the better."[19]

| Year | Country |

|---|---|

| 1264 | Poland |

| 1791 | France[20][9] |

| 1796 | Batavian Republic – Netherlands |

| 1808 | Grand Duchy of Hesse |

| 1808 | Westphalia[21] |

| 1811 | Grand Duchy of Frankfurt[22] |

| 1812 | Mecklenburg-Schwerin[23] |

| 1812 | Prussia[24] |

| 1813 | Kingdom of Bavaria[25] |

| 1826 | Maryland (the Jew Bill revised Maryland law to permit a Jew to hold office if he professed belief in "a future state of rewards and punishments".) |

| 1828 | Württemberg |

| 1830 | Belgium |

| 1830 | Greece |

| 1831 | Jamaica[26] |

| 1832 | Canada (Lower Canada (Quebec))[27] |

| 1833 | Electorate of Hesse |

| 1834 | United Netherlands |

| 1839 | Ottoman Empire[28] |

| 1842 | Kingdom of Hanover |

| 1848 | Nassau[29] |

| 1849 | Hungarian Revolutionary Parliament declared and enacted the emancipation of Jews, the law was repealed by the Habsburgs after the joint Austrian-Russian victory over Hungary[30] |

| 1849 | Denmark[31] |

| 1849 | Hamburg[32] |

| 1856 | Switzerland |

| 1858 | United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland |

| 1861 | Italy (Italy had not existed as a unified nation prior to 1861 and had previously been divided amongst several foreign entities) |

| 1862 | Baden |

| 1863 | Holstein[33] |

| 1864 | Free City of Frankfurt |

| 1865 | Mexico |

| 1867 | Austrian Empire |

| 1867 | Restoration of the law of emancipation in Kingdom of Hungary after the Austro-Hungarian Compromise |

| 1869 | North German Confederation |

| 1870 | Sweden-Norway (1851 in Norway) |

| 1871 | Germany[34] |

| 1877 | New Hampshire (last US state to lift restrictions limiting public office to Protestants) |

| 1878 | Bulgaria |

| 1878 | Serbia |

| 1890 | Brazil[35] |

| 1911 | Portugal |

| 1917 | Russia |

| 1918 | Finland |

| 1923 | Romania |

| 1945–1949 | West Germany[36] |

| 1978 | Spain[37] |

Consequences edit

Emancipation, integration, and assimilation edit

The newfound freedom of Jews in places such as France, Italy, and Germany, at least during the Empire, permitted many Jews to leave the ghettos, benefitting from and contributing to wider society for the first time.[38] Thus, with emancipation, many Jews' relationships with Jewish belief, practice, and culture evolved to accommodate a degree of integration with secular society. Where Halacha (Jewish law) was at odds with local law of the land, or where Halacha did not address some aspect of contemporary secular life, compromise was often sought in the balancing of religious and secular law, ethics, and obligations. Consequently, while some remained firm in their established Jewish practice, the prevalence of emancipated Jewry prompted gradual evolution and adaptation of the religion, and the emergence of new denominations of Judaism including Reform during the 19th century, and the widely practiced Modern Orthodoxy, both of which continue to be practiced by strong Jewish communities today.[39][40][41]

Critics of the Haskalah lament the emergence of inter-religious marriage in secular society, as well as the dilution of Halacha and Jewish tradition, citing waning religiosity, dwindling population numbers, or poor observance as contributors to the potential disappearance of Jewish culture and dispersion of communities.[42][43] In contrast, others cite antisemitic events such as the Holocaust as more detrimental to the continuity and longevity of Judaism than the Haskalah.[44] Emancipation offered Jewish people civil rights and opportunities for upward mobility, and assisted in dousing the flames of widespread Jew-hatred (though never completely, and only temporarily). This enabled Jews to live multifaceted lives, breaking cycles of poverty, enjoying the spoils of Enlightened society, while also maintaining strong Jewish faith and community.[45][46] While this element of emancipation gave rise to antisemitic canards relating to dual loyalties, and the successful upward mobility of educated and entrepreneurial Jews saw pushback in antisemitic tropes relating to control, domination, and greed, the integration of Jews into wider society led to a diverse tapestry of contribution to art, science, philosophy, and both secular and religious culture.

See also edit

References edit

- ^ Barnavi, Eli. "Jewish Emancipation in Western Europe". My Jewish Learning. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ Ettinger, Shmuel. "Jewish Emancipation and Enlightenment". Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ "Socialism". Jewish Virtual Library. American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ Beauchamp, Zack (14 May 2018). "What is Zionism?". Vox.com. Vox Media, Inc. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ "YIVO | Fareynikte". yivoencyclopedia.org. Retrieved 2023-03-09.

- ^ "Washington Letter". Archived from the original on 2020-11-29. Retrieved 2019-12-07.

- ^ Leeser, I. "Jewish Emancipation," 1845, The Occident and American Jewish Advocate, vol III, no 3, http://www.jewish-history.com/Occident/volume3/jun1845/emancipation.html

- ^ Sorkin, David, Jewish Emancipation, Princeton University Press, 2019

- ^ a b Paula E. Hyman, The Jews of Modern France (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), pp. 17–18.

- ^ Vlessing, Odette. "The Jewish community in transition; from acceptance to emancipation." Studia Rosenthaliana 30.1 (1996): 195-212.

- ^ Ramakers, J. J. M. "Parallel processes? The emancipation of Jews and Catholics in the Netherlands 1795/96-1848." Studia Rosenthaliana 30.1 (1996): 33-40.

- ^ a b "Emancipation". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ Henriques, Henry Straus Quixano (October 1905). "The Civil Rights of English Jews". The Jewish Quarterly Review. The Jews and the English Law. 18 (1). Oxford: Horace Hart, Printer to the University: 40–83. doi:10.2307/1450822. hdl:2027/mdp.39015039624393. ISSN 0021-6682. JSTOR 1450822. OCLC 5792006336.

A Jew was, unless he had previously renounced his religion, incapable of becoming a clergyman; and therefore Jews who had committed crimes and been convicted of them could not, according to the opinion of many great legal writers, avail themselves of the benefit of clergy which other malefactors, on a first conviction for felony were at liberty to plead in mitigation of punishment.

- ^ Nicholas, de Lange; Freud-Kandel, Miri; C. Dubin, Lois (2005). Modern Judaism. Oxford University Press. pp. 30–40. ISBN 978-0-19-926287-8.

- ^ a b Sharfman, Glenn R., "Jewish Emancipation", in Encyclopedia of 1848 Revolutions

- ^ Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger: Europa im Jahrhundert der Aufklärung. Stuttgart: Reclam, 2006 (2nd edition), 268.

- ^ In the German original: "Es werden den Bekennern des jüdischen Glaubens die denselben in [von, respectively] den einzelnen Bundesstaaten bereits eingeräumten Rechte erhalten." Cf. Heinrich Graetz, Geschichte der Juden von den ältesten Zeiten bis auf die Gegenwart: 11 vols., Leipzig: Leiner, 1900, vol. 11: 'Geschichte der Juden vom Beginn der Mendelssohnschen Zeit (1750) bis in die neueste Zeit (1848)', p. 317. Emphasis not in the original. Reprint of the edition revised by the author: Berlin: Arani, 1998, ISBN 3-7605-8673-2.

- ^ C. Dubin, Lois. Modern Judaism. Oxford University Press. pp. 32–33.

- ^ "THE DEVELOPMENT OF MODERN ANTI-SEMITISM: images pg.21". Friends-partners.org. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-02-17.

- ^ "Admission of Jews to Rights of Citizenship," 27 September 1791, 1791-09-27, retrieved 2021-12-04

- ^ However, reversed by the Westphalian successor states in 1815. Cf. for introduction and reversion Heinrich Graetz, Geschichte der Juden von den ältesten Zeiten bis auf die Gegenwart: 11 vols., Leipzig: Leiner, 1900, vol. 11: 'Geschichte der Juden vom Beginn der Mendelssohnschen Zeit (1750) bis in die neueste Zeit (1848)', p. 287. Reprint of the edition of last hand: Berlin: arani, 1998, ISBN 3-7605-8673-2.

- ^ Reversed at the dissolution of the grand duchy in 1815.

- ^ On February 22, cf. Heinrich Graetz, Geschichte der Juden von den ältesten Zeiten bis auf die Gegenwart: 11 vols., Leipzig: Leiner, 1900, vol. 11: 'Geschichte der Juden vom Beginn der Mendelssohnschen Zeit (1750) bis in die neueste Zeit (1848)', p. 297. Reprint of the edition of last hand: Berlin: arani, 1998, ISBN 3-7605-8673-2.

- ^ On March 11, cf. Heinrich Graetz, Geschichte der Juden von den ältesten Zeiten bis auf die Gegenwart: 11 vols., Leipzig: Leiner, 1900, vol. 11: 'Geschichte der Juden vom Beginn der Mendelssohnschen Zeit (1750) bis in die neueste Zeit (1848)', pp. 297seq. Reprint of the edition of last hand: Berlin: arani, 1998, ISBN 3-7605-8673-2.

- ^ Deutsch-jüdische Geschichte in der Neuzeit. Michael A. Meyer, Michael Brenner, Mordechai Breuer, Leo Baeck Institute. München: C.H. Beck. 1996–2000. ISBN 3-406-39705-0. OCLC 34707114.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Finding Your Roots, PBS, September 23, 2014

- ^ Bélanger, Claude. "An Act to Grant Equal Rights and Privileges to Persons of the Jewish Religion (1832)". Quebec History. Marianopolis College. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- ^ By order of the Sultan, equal rights were granted to non-Muslims, including Jews, in 1839 as part of the Tanzimat reforms.

- ^ Introduced on December 12, 1848.

- ^ The Hungarian Diet declared the full emancipation of the Jews by law in the realm on July 28, 1849. However, this would soon be rolled back by the Hungarians' defeat at the hands of the Russian Army barely two weeks later on August 13, which marked the failure of the Hungarian Revolution as the Austrian Empire tried to abolish Hungary's constitution and territorial integrity. The emancipation of the Hungarian Jews would not be restored until the Compromise of 1867.

- ^ By the Constitution of Denmark of June 5, 1849.

- ^ By introduction of the basic freedoms as decided by the National Assembly, adopted for Hamburg's law on February 21, 1849.

- ^ By law on the Affairs of the Jews in the Duchy of Holstein on July 14, 1863.

- ^ For the status of Jews in the states, which united in 1871 to constitute Germany see the respective regulations of the principalities and states that preceded the 1871 unification of Germany.

- ^ Since 1810 Jews already had partial freedom of religion, that was completely guaranteed in 1890 after the proclamation of the Republic

- ^ After the fall of the Nazis, the Jews recovered their civil rights.

- ^ Oliva, Javier García (20 Aug 2008). "Religious Freedom in Transition: Spain". Religion, State and Society. 36 (3): 269–281. doi:10.1080/09637490802260336. ISSN 0963-7494.

- ^ "The Haskalah". Jewish Virtual Library.

- ^ Samet, Moshe (1988). "The Beginnings of Orthodoxy". Modern Judaism. 8 (3): 249–269. doi:10.1093/mj/8.3.249. JSTOR 1396068.

- ^ Zalkin, M. (2019). " The Relations between the Haskalah and Traditional Jewish Communities". In The History of Jews in Lithuania. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill | Schöningh. doi: https://doi.org/10.30965/9783657705757_011

- ^ Book: Haskalah and Beyond: The Reception of the Hebrew Enlightenment and the Emergence of Haskalah Judaism, Moshe Pelli, University Press of America, 2010

- ^ Grobgeld, David; Bursell, Moa (2021). "Resisting assimilation – ethnic boundary maintenance among Jews in Sweden". Distinktion: Journal of Social Theory. 22 (2): 171–191. doi:10.1080/1600910X.2021.1885460. S2CID 149297225.

- ^ Lemberger, Tirza (2012). "Haskalah and Beyond: The Reception of the Hebrew Enlightenment and the Emergence of Haskalah Judaism (Review)". Hebrew Studies. 53: 420–422. doi:10.1353/hbr.2012.0013. S2CID 170774270.

- ^ "If Not for the Holocaust, There Could Have Been 32 Million Jews in the World Today, Expert Says".

- ^ "Antisemitism from the Enlightenment to World War I".

- ^ Richarz, M. (1975). "Jewish Social Mobility in Germany during the Time of Emancipation (1790–1871)." The Leo Baeck Institute Yearbook, 20(1), 69–77. doi:10.1093/leobaeck/20.1.69

Bibliography edit

- Battenberg, Friedrich (2017), Jewish Emancipation in the 18th and 19th Centuries, EGO - European History Online, Mainz: Institute of European History, retrieved: March 17, 2021 (pdf).

- Christian Wilhelm von Dohm. Über die bürgerliche Verbesserung der Juden (Berlin /Stettin 1781). Kritische und kommentierte Studienausgabe. Hrsg. von Wolf Christoph Seifert. Wallstein, Göttingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-8353-1699-7.

- David Feuerwerker. L'Émancipation des Juifs en France. De l'Ancien Régime à la fin du Second Empire. Paris: Albin Michel, 1976 ISBN 2-226-00316-9

- Heinrich Graetz, Geschichte der Juden von den ältesten Zeiten bis auf die Gegenwart: 11 vols., Leipzig: Leiner, 1900, vol. 11: Geschichte der Juden vom Beginn der Mendelssohnschen Zeit (1750) bis in die neueste Zeit (1848), reprint of the edition of last hand; Berlin: arani, 1998, ISBN 3-7605-8673-2

- Hyman, Paula E. The Jews of Modern France. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

- Sorkin, David (2019). Jewish Emancipation: A History Across Five Centuries. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-16494-6.

External links edit

- History of Frankfurt (German Wikipedia)

- Jewish Emancipation, Ohio State University

- Emancipation, Mendelssohn, and the Rise of Reform Thinktorah.org, Rabbi Menachem Levine

- Des Juifs contre l'émancipation. De Babylone à Benny Lévy Archived 2009-02-15 at the Wayback Machine [Jews Against Emancipation: From Babylon to Benny Lévy], Labyrinthe. Atelier interdisciplinaire (in French), 2007 (Special issue)

- 'Emancipation,' A Story Of European Jews' Liberation, NPR books

- Jewish Emancipation In The East

- Jewish Emancipation on The Museum of Family History