Jay Cooke State Park

Jay Cooke State Park is a state park of Minnesota, United States, protecting the lower reaches of the Saint Louis River. The park is located about 10 miles (16 km) southwest of Duluth and is one of the ten most visited state parks in Minnesota. The western half of the park contains part of a rocky, 13-mile (21 km) gorge. This was a major barrier to Native Americans and early Europeans traveling by canoe, which they bypassed with the challenging Grand Portage of the St. Louis River.[2] The river was a vital link connecting the Mississippi waterways to the west with the Great Lakes to the east.

| Jay Cooke State Park | |

|---|---|

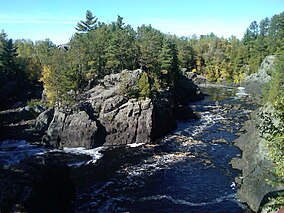

The St. Louis River in Jay Cooke State Park | |

| Location | Carlton, Minnesota, United States |

| Coordinates | 46°38′59″N 92°19′51″W / 46.64972°N 92.33083°W |

| Area | 8,125 acres (32.88 km2) |

| Elevation | 928 ft (283 m)[1] |

| Established | 1915 |

| Governing body | Minnesota Department of Natural Resources |

Jay Cooke State Park CCC/Rustic Style Historic District | |

The River Inn is the visitor center for the park and was built by the Civilian Conservation Corps | |

| Location | Carlton County, Minnesota, Off MN 210 east of Carlton |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Carlton, Minnesota |

| Coordinates | 46°39′15″N 92°22′17″W / 46.65417°N 92.37139°W |

| MPS | Minnesota State Park CCC/WPA/Rustic Style MPS |

| NRHP reference No. | 89001665 |

| Added to NRHP | June 11, 1992 |

Jay Cooke State Park CCC/WPA/Rustic Style Picnic Grounds | |

1934 water tower/latrine at Oldenburg Point | |

| Location | Off MN 210 SE of Forbay Lake, Thomson Township |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 46°39′20″N 92°21′8″W / 46.65556°N 92.35222°W |

| MPS | Minnesota State Park CCC/WPA/Rustic Style MPS |

| NRHP reference No. | 92000640 |

| Added to NRHP | June 11, 1992 |

Jay Cooke State Park CCC/WPA/Rustic Style Service Yard | |

| |

| Location | Off MN 210 E of Forbay Lake, Thomson Township |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 46°39′40″N 92°20′50″W / 46.66111°N 92.34722°W |

| MPS | Minnesota State Park CCC/WPA/Rustic Style MPS |

| NRHP reference No. | 92000642 |

| Added to NRHP | June 11, 1992 |

Today Minnesota State Highway 210 runs through Jay Cooke State Park. The 9 miles (14 km) of the route between Carlton and Highway 23—which include the park—are designated the Rushing Rapids Parkway, a state scenic byway.[3]

The park is named for Pennsylvania financier Jay Cooke, who had developed a nearby power plant, which is still in use.[4] The Grand Portage trail and three districts of 1930s park structures are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

History

editThe first 2,350 acres (9.5 km2) of land on which the park is situated were donated to the state by the Saint Louis Power Company in 1915. The park remained generally undeveloped until 1933, when a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp was established on the site. The CCC camp built a rustic swinging bridge over the St. Louis River just slightly downstream from some torrential rapids and waterfalls. This camp also built a picnic shelter. The camp was disbanded in 1935, but a second camp was set up in 1939. This camp rebuilt the swinging bridge and built the River Inn, which now houses the visitor center. This camp was disbanded in 1942, shortly before the federal government ended the CCC entirely. In 1945 the state began to add more land to the park, eventually giving it its current size of 8,818 acres (3,569 ha).

In 2012 the Duluth area experienced a record-setting rainstorm that resulted in flooding that filled the gorge with debris, devastated the park's roads and trails, and destroyed the historic Swinging Bridge that crosses the St. Louis River. By 2014, extensive repair work had repaired most of the trails and replaced the bridge, and further work is ongoing. In June 2015 the park celebrated its 100-year anniversary; today Jay Cooke State Park is one of the ten most visited state parks in Minnesota, with 378,000 visitors in 2014.[5]

Architecture

editJay Cooke is noted for its Rustic Style historical structures. These structures were built by the Civilian Conservation Corps between 1933 and 1942. All the major landmarks in Jay Cooke are built with local basalt or gabbro stone and dark planks and logs. Most famous of all landmarks is the swinging bridge, which is one of only two suspension bridges in any Minnesota state park. The bridge was designed by Oscar Newstrom. It runs 200 feet (61 m) long, 126 feet (38 m) of which run over the river itself. It is supported by two large concrete pylons also faced with gabbro. The bank of the river near the River Inn is too steep to walk along, so anyone who wishes to hike the length of the river generally must cross this bridge.

In the major floods of June 20, 2012, the swinging bridge was severely damaged. According to an early report from the Pine Journal, at least one stone pillar and half of another were washed away, and the bridge decking was "twisted and mangled."[6]

The CCC structures are grouped into three historic districts which are separately listed on the National Register of Historic Places. These districts are the Rustic Style District, including the River Inn and Swinging Bridge; the Rustic Style Picnic Grounds, including the shelter, water tower and latrine, and drinking fountain; and the Rustic Style Service Yard, including the custodian's cabin and pump house.[7]

Early canoe route

editMinnesota geography is dominated by three major watersheds which carry the surface waters of the state north to Hudson Bay, east to the Great Lakes, and south into the Mississippi River. The rivers, creeks, and associated lakes within these drainage basins essentially describe the route geography of the thoroughfares used by American Indians for centuries, and later by European explorers, missionaries, and fur traders. But water travel was subject to interruption caused by rapids, falls, or shallows, and not all of the major lakes and rivers were interconnected, making it necessary to portage from time to time.

The earliest North American fur trading did not include long-distance transportation of the furs after they were obtained by trade with the Indians; it started with trading near settlements or along the coast or waterways accessible by ship. But later, Coureur des bois achieved business advantages by traveling deeper into the wilderness and trading there. By 1681, the French authorities decided to control the traders. Also, as the trading process moved deeper into the wilderness, transportation of the furs (and the products to be traded for furs) became a larger part of the fur trading business process. The authorities began a process of issuing permits. Those travelers associated with the canoe transportation part of the licensed endeavor became known as voyageurs, a term which literally means "traveler" in French.

The rocky gorge of the St. Louis River was not navigable to canoes, so Native Americans blazed a 6.5-mile (10.5 km) portage around it. Later, the voyageurs employed it too and dubbed it the "Grand Portage of the St. Louis."[8] It was a rough trail of steep hills and swamps that began at the foot of the rapids above the present day Fond du Lac ("back of the lake") neighborhood and climbed some 450 feet (140 m) to the present-day city of Carlton.[9] Above Carlton travelers proceeded upstream and continued on to Lake Vermilion and the Rainy River. Or they may have traveled southwest up the East Savanna River, portaged the grueling six mile long Savanna Portage (now a state park), and then paddled on to the Mississippi River.

The Saint Louis River Grand Portage was divided into 19 pauses (stopping/resting places) spaced one-third to one-half mile apart. To portage the freight, each voyageur carried two or three packs weighing up to 90 pounds each. These were supported by a portage strap, which passed around the voyageur's forehead and reached to the small of his back. Once he reached a pause with his load, the voyageur would jog back to the last stop for more packs. It took an average of three to five days for a crew to complete the Grand Portage, sometimes longer under bad conditions. It was backbreaking labor, and the voyageurs would be plastered with mud and covered with mosquito and fly bites.

The Grand Portage was still in use as late as 1870, but a new railroad meant the end of the old passage. Also, fur animals became less plentiful and the amount of North American fur trading declined.

A portion of the trail has been renovated for hiking and information is available at the park shelter.[10]

Geology

editBedrock

editThe oldest bedrock visible in Jay Cooke State Park is the Thomson Formation, dating to the Paleoproterozoic era 1.9 billion years ago. The southernmost unit of the Animikie Group, the Thomson Formation is named for the nearby town of Thomson, as this is its type locality.[11] It began as mud, silt, and clayey sand deposited by turbidity currents at the bottom of a deep sea.[8] These sediments compacted into horizontal layers of shale and greywacke.[12] Ripple marks are still visible in the resulting rock, but there are no signs of life as complex organisms had not yet appeared.[13] 1.85 billion years ago a mountain-building event to the south called the Penokean orogeny subjected the sediments to intense pressure and heat.[8] This metamorphosed the shale into dark, thin layers of slate.[13] The slate also developed a pattern of vertical cleavage, but the more massive greywacke deposits were largely resistant to this foliation.[8] Both types of rocks, though, were folded and fractured, giving them the wildly tilted appearance that distinguishes them today.[12]

1.1 billion years ago the Midcontinent Rift System cracked the Thomson Formation, creating southwest-to-northeast trending fractures. Volcanic eruptions sent magma through these gaps, forming the distinctive flood basalts of Minnesota's North Shore.[11] Magma remaining in the underground fractures cooled more slowly into gabbro.[14] Several of these dikes are exposed around the swinging bridge and also just outside the park where Highway 210 crosses the river below the Thomson Dam. They are nearly the same color as the Thomson slate, but can be distinguished by their horizontal columnar joints and lack of slaty cleavage.[11]

Around Jay Cooke State Park, the basalt from the Midcontinent Rift eruptions eroded away long ago. In fact the rock layer immediately above the Thomson Formation is the Fond du Lac Formation, which dates from the late Mesoproterozoic era, an unconformity of about 800 million years.[2][11] This red and brown sedimentary layer is composed of sandstone, siltstone, and shale. The bottommost layer is a conglomerate of quartz pebbles originating from quartz veins in the Thomson Formation. Above, cross-bedding of the sandstone, several layers of mud-chip conglomerate, and mudcracks indicate deposition in a broad river plain. Only small portions of the Fond du Lac Formation are visible within Jay Cooke, primarily along the Little River in the northeast part of the park.[2] Better exposures are found in Fond du Lac, a neighborhood on the outskirts of Duluth just outside the park's eastern border. Many of Duluth's brownstone buildings were constructed from quarries there.[11][15]

Glaciation

editAlthough the rocky riverbed around the swinging bridge is Jay Cooke's best-known feature, this Precambrian formation is only exposed in a portion of the park.[13] Elsewhere the land is characterized by glaciation. Most of the park lies on red clay sediments deposited 10,000 years ago at the bottom of a proglacial lake.[12]

Ice sheets covered Minnesota as many as twenty times over the 2 million years of the Quaternary glaciation, each advance largely obliterating the results of the previous. Nearly all of Minnesota's glacial landforms derive from the last of them, the Wisconsin glaciation.[11] One feature of this time in the park are the rock ridges near the campground, scoured smooth by the glacier and known as roches moutonnées.[13] Another is the Thomson Moraine, a ridge along the northwest boundary. This terminal moraine comprises rock and debris dropped at the farthest reach of the Laurentide Ice Sheet's Superior Lobe.[11]

As the climate warmed at the end of the Pleistocene epoch, the Superior Lobe shrank northeastward. The deep basin gouged by the ice filled with meltwater around 12,000 years ago as Lake Duluth. Since the eastern shore was formed by the towering wall of the ice sheet, the lake was 500 feet (150 m) higher than modern Lake Superior. The St. Louis River, flowing into Lake Duluth, dropped its sediment load onto the lakebed, forming layers of silt and sand alternating with clay.[11] The clay layers include incongruous cobbles and boulders, dropstones which melted free from icebergs floating above.[8]

As the Laurentide Ice Sheet receded further, lower elevation outlets were exposed and the lake level dropped significantly. The St. Louis River flowed across the now-exposed lakebed, etching wide and changeable meanders into the soft sediments. On the south side of the river are several steep, curving valleys that are former meanders. Slumping of the unstable clay walls further widened the main valley.[11] The river's downcutting eventually passed through the Pleistocene lake sediments and into the Precambrian bedrock, exposing the rocky, 13-mile (21 km) gorge that characterizes the western half of the park.[2]

Wildlife

editThe park is inhabited by 46 species of mammals and is an important wintering area for White-tailed Deer. Black Bears, Wolf packs, and Coyotes have been spotted within the park. The park houses 173 species of birds including the Pileated Woodpecker, Northern Harrier, and the Great Blue Heron. Sixteen species of (non-venomous) reptiles are found within the park.

Recreation

editThe park has over 50 miles of hiking trails, with several scenic overlooks over the Saint Louis River. Certain trails, such as the Greely Creek Trail, Triangle Trail, and Gill Creek Trail, are also open to mountain biking. The Willard Munger State Trail runs through the park. From the park, one can bike or skate to Duluth, about 15 miles (24 km) away. This segment of the trail features very scenic views of the Duluth harbor, as well as cuts in the rock made for the building of the St. Paul and Duluth Railroad.

The North Country National Scenic Trail, a hiking trail that stretches approximately 4,800 miles (7,700 km) from Maine Junction in Vermont to Lake Sakakawea State Park in central North Dakota, passes through the park. It is the longest of the eleven National Scenic Trails and was designed to provide outdoor recreational opportunities in some of the America's outstanding landscapes.

Park activities include camping, hiking, biking, cross-country skiing and kayaking. Park rangers offer over 400 naturalist outreach events each year including nature walks, evening campfire talks, snowshoe-building lessons, and geocaching. As part of the "I Can!" program for kids and families, the park provides a number of classes and guides to help with camping skills, canoeing, fishing, archery, and other activities.[5]

Brown trout are taken in the Saint Louis River (some walleye and northern in slower stretches) and in Otter Creek. Brook trout are found in Silver and Otter creeks. There are two dams on the Saint Louis River near the park; the Thomson Dam (near the northwest boundary) and the Fond du Lac Dam (near the northeast boundary).

References

edit- ^ "Jay Cooke State Park". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. January 11, 1980. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Ojakangas, Richard W.; Matsch, Charles L. (1982). Minnesota's Geology. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-0950-0.

- ^ Bewer, Tim (January 23, 2007). Moon Handbooks: Minnesota. Avalon Travel Publishing. ISBN 978-1-56691-927-2.

- ^ Kris Hiller (narrator, Park Naturalist). Jay Cooke (mp3). Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- ^ a b Myers, John (June 11, 2015). "Jay Cooke State Park Turns 100". Duluth News Tribune. Archived from the original on July 4, 2015. Retrieved July 3, 2015.

- ^ Peterson, Jana (June 20, 2012). "Epic flooding sweeps through Carlton County". Pine Journal. Cloquet, Minn. Archived from the original on January 31, 2013.

- ^ "Rustic Style Resources in Minnesota State Parks: Minneopa State Park". Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Ojakangas, Richard W. (2009). Roadside Geology of Minnesota. Missoula, Mont.: Mountain Press Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-87842-562-4.

- ^ Luukkonen, Larry (2007), Between the Waters: Tracing the Northwest Trail from Lake Superior to the Mississippi, Duluth: Dovetailed Press, pp. 32–35, ISBN 978-0-9765890-4-4

- ^ Lundy, John (June 9, 2015). "Portion of Grand Portage trail rediscovered in Jay Cooke State Park". Duluth News Tribune. Retrieved July 4, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Green, John C. (1996). Geology on Display: Geology and Scenery of Minnesota's North Shore State Parks. St. Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. ISBN 0-9657127-0-2.

- ^ a b c Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (2013). "Jay Cooke State Park". Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Sansome, Constance J. (1983). Minnesota Underfoot: A Field Guide to the State's Outstanding Geologic Features. Stillwater, Minn.: Voyageur Press. ISBN 0-89658-036-9.

- ^ "Jay Cooke State Park" (PDF). State of Minnesota, Department of Natural Resources. May 2012. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- ^ "Duluth Brownstone Quarrying". Zenith City Press. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

External links

edit- Jay Cooke State Park official website

- An Environmental History of Oldenburg Point

- Vogel, Robert C.; David G. Stanley (1992). "Portage Trails in Minnesota, 1630s-1870s" (pdf). Multiple Property Documentation Form. US Dept. of the Interior, Nat'l Park Service. Retrieved December 1, 2013.

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. MN-53, "Jay Cooke State Park, Pedestrian Suspension Bridge, crossing St. Louis River, Thomson, Carlton County, MN", 4 photos, 1 photo caption page