Jacques-Laurent Bost (6 May 1916 – 21 September 1990) was a French journalist and close friend of Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir.[1][2]

Jacques-Laurent Bost | |

|---|---|

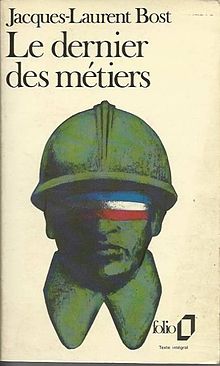

The cover of Bost's war novel, Le dernier des métiers | |

| Born | 6 May 1916 Le Havre, Normandy, France |

| Died | 21 September 1990 (aged 74) Paris, France |

| Pen name | Claude Tartare |

| Occupation | Journalist |

| Notable awards | Croix de Guerre |

| Spouse | Olga Kosakiewicz |

| Relatives | Pierre Bost (brother) |

Biography

editBost was born the youngest of ten children on 6 May 1916 in Le Havre, Normandy, France to Pastor Charles Bost.[3][4][5] One of his siblings, older brother Pierre, was a screenwriter and author[4] and journalist Serge Lafaurie was his nephew.[citation needed] Bost was known as "little Bost" in the 1930s because Pierre had already made a name for himself.[2] One of Bost's teachers at Lycée du Havre was Jean-Paul Sartre, with who he became lifelong friends.[6][1]

Bost was a second-class infantryman in the French Army during World War II until being injured in May/June 1940.[1][7][2][8] He and Simone de Beauvoir exchanged a number of letters while he was deployed; their correspondence would later be published by Beauvoir's daughter Sylvie under the title Correspondance croisée.[9] Following his service, for which he received a Croix de Guerre, he worked as a war correspondent for Combat.[5][10] Bost came across Dachau just hours after the American troops during one of his assignments.[5]

Bost wrote for L'Express after Combat but left in 1964 to co-found L'Obs with Jean Daniel, Serge Lafaurie, K. S. Karol, and André Gorz.[11][12][5] During his career, he also wrote for the satire weekly Le Canard enchaîné and Sartre's Les Temps modernes.[13][14][15][2] At times, he published under the pseudonym Claude Tartare.[citation needed] Le Dernier des métiers (1946) was the only book Bost wrote and published during his life.[2][16] The character Boris in Sartre's Les Chemins de la liberte is based on Bost; Beauvoir also mentioned him in La Force de l'age.[2]

In addition to being a journalist, Bost was a screenwriter and a translator. In 1947, he helped Jean Delannoy adapt a Sartre drama into the film Les jeux sont faits.[17] He wrote scripts for Dirty Hands (1951), La Putain respectueuse (1952), Les héros sont fatigués (1955), and Oh! Que Mambo! (1959), several of which were adaptations of stories by Sartre, and dialogue for Ca va barder! (1955), El amor de Don Juan (1956), and Le vent se lève (1959).[18] His translations include the French versions of the following English books: Little Men, Big World by William Burnett, Strictly for Cash by James Hadley Chase, This is Dynamite by Horace McCoy, The Sure Hand of God by Erskine Caldwell, Fast One by Paul Cain, How Sleeps The Beast by Don Tracy, The Dead Tree Gives No Shelter by Virgil Scott, and Lazarus #7 by Richard Sale.[9] He was also part of the first performance of Picasso's Desire Caught by the Tail along with Sartre, Beauvoir, Raymond Queneau, Zanie Campan, and Dora Maar; he the part of Silence.[19] In 1948, Bost taught philosophy at the University of Paris.[7]

Bost and Beauvoir began their affair in 1939 and he was described as her second love only to Sartre.[6] He married Olga Kosakiewicz, one of the many women involved in a ménage à trois with Beauvoir and Sartre, but Bost and Beauvoir continued their affair in secret.[6][20][1] Early in their friendship, Bost is thought to have had sex with Natalie Sorokin at the suggestion of Beauvoir.[21] Bost and Olga had at least one child, Bernard Edouard.[22] Olga died in 1985.[23]

References

edit- ^ a b c d Zetterström, Margareta (2017-10-04). "Kärleksbrev som går i kors" (in Swedish). Dixikon. Retrieved 2022-02-12.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Trois disparitions Jacques-Laurent Bost L'éternel jeune homme de la famille existentialiste" (in French). Le Monde. 1990-09-23. Retrieved 2022-02-12.

- ^ "Décès le 21 septembre 1990 à Paris 15e Arrondissement, Paris, Île-de-France (France)" (in French). Archives Ouvertes. 2020. Retrieved 2022-02-12.

- ^ a b "À PROPOS" (in French). François Ouellet et UQAC. n.d. Retrieved 2022-02-12.

- ^ a b c d Devarrieux, Claire (2004-04-22). "Bost, le bon type". Liberation. Retrieved 2022-02-12.

- ^ a b c "Wendy and the Lost Girls". The Daily Telegraph. London, England. 1992-01-25. p. 31. Retrieved 2022-02-12 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "War's stark horror caught by novelist". The Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, CA. 1948-08-18. p. 4. Retrieved 2022-02-12 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ O'Dell, Scott (1948-07-17). "Realism & art combined in French novel". Daily News. Los Angeles, CA. p. 4. Retrieved 2022-02-12 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "JACQUES-LAURENT BOST" (in French). fnac. n.d. Retrieved 2022-02-13.

- ^ Zavriew, ANDRÉ (2004). "Beauvoir-Bost ou l'amour fou". Revue des Deux Mondes: 148–152. JSTOR 44190627. Retrieved 2022-02-12.

- ^ a b "Deaths". The Guardian. London, England. 1990-09-28. p. 27. Retrieved 2022-02-12 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "André Gorz, 1923–2007". Radical Philosophy. 2008. Retrieved 2022-02-13.

- ^ "Ruud Welten, "Wie is er bang voor Simone de Beauvoir? Over feminisme, existentialisme, God, liefde en seks", een uitgave van Boom" (in Dutch). Stretto. 2020-09-19. Retrieved 2022-02-13.

- ^ "Notes on books of note". The Times. Shreveport, LA. 1957-06-30. p. 37. Retrieved 2022-02-12 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Davies, Howard (1987). Sartre and 'Les Temps Modernes'. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521111508.

- ^ "'The Last Profession'". The Indianapolis Star. Indianapolis, IN. 1948-07-18. p. 24. Retrieved 2022-02-12 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Slate French film". The Troy Record. Troy, NY. 1970-12-02. p. 37. Retrieved 2022-02-12 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Jacques-Laurent Bost". BFI. n.d. Archived from the original on July 12, 2020. Retrieved 2022-02-13.

- ^ Halász Brassaï, Gyula; Picasso, Pablo; Miller, Henry V.; Fraisse, Genevieve. Conversations with Picasso. p. 200.

- ^ "Sartre: The lovers' contract". The Observer. London, England. 1987-10-11. p. 21. Retrieved 2022-02-12 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Donnelly, Pat (2005-12-11). "Beauty and the sexually insecure Beast". The Ottawa Citizen. Ottawa, Canada. p. C10. Retrieved 2022-02-12 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Sheila Mary Towle becomes bride of Bernard Bost in France". The San Francisco Examiner. San Francisco, CA. 1958-05-18. p. 10. Retrieved 2022-02-12 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Bair, Deirdre (1986). "[Some personal reflections]". Yale French Studies (62): 211–215. doi:10.2307/2930237. JSTOR 2930237. Retrieved 2022-02-12.