Isaac Ilyich Levitan[a] (Russian: Исаа́к Ильи́ч Левита́н; 30 August [O.S. 18 August] 1860 – 4 August [O.S. 22 July] 1900) was a classical Russian landscape painter who advanced the genre of the "mood landscape".

Isaac Levitan | |

|---|---|

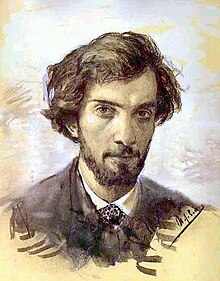

Isaac Levitan, Self portrait (1880) | |

| Born | Isaac Ilyich Levitan 30 August [O.S. 18 August] 1860 |

| Died | 4 August [O.S. 22 July] 1900 (aged 39) |

| Education | Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture |

| Known for | Painting |

| Notable work | Autumn day. Sokolniki (1879) Over Eternal Peace (1894) |

| Movement | Realism, Peredvizhniki, Impressionism |

| Awards | Member Academy of Arts (1898) |

| Patron(s) | Pavel Tretyakov, Savva Mamontov |

Life and work edit

Youth edit

Isaac Levitan was born in a shtetl of Kibarty, Augustów Governorate in Congress Poland, a part of the Russian Empire (present-day Lithuania) into a poor but educated Jewish family. His father Elyashiv Levitan was the son of a rabbi, completed a Yeshiva and was self-educated. He taught German and French in Kowno and later worked as a translator at a railway bridge construction for a French building company. At the beginning of 1870 the Levitan family moved to Moscow.

In September 1873, Isaac Levitan entered the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture where his older brother Avel had already studied for two years. After a year in the copying class Isaac transferred into a naturalistic class, and soon thereafter into a landscape class. Levitan's teachers were the famous Alexei Savrasov, Vasily Perov and Vasily Polenov. In 1875 the school admitted Nikolai Chekhov, brother of the Russian writer, Anton Chekhov who would later become Levitan's closest friend.[1]

In 1875, his mother died, and his father fell seriously ill and became unable to support four children; he died in 1877. The family slipped into abject poverty. As patronage for Levitan's talent and achievements, his Jewish origins and to keep him in the school, he was given a scholarship.

Early work edit

In 1877, Isaac Levitan's works were first publicly exhibited and earned favorable recognition from the press. After Alexander Soloviev's assassination attempt on Alexander II, in May 1879, mass deportations of Jews from big cities of the Russian Empire forced the family to move to the suburb of Saltykovka, but in the fall officials responded to pressure from art devotees, and Levitan was allowed to return. During that year Levitan painted Осенний день. Сокольники (Autumn day. Sokolniki), which depicted a long path in a Moscow park. When Nikolay Chekhov saw the work he told Levitan the path needed someone walking on it, so Chekhov painted a woman in a black dress walking toward the viewer. This kind of collaboration between a genre painter such as Chekhov and a landscape painter such as Levitan was common in the school.[1] In 1880 the famous philanthropist and art collector Pavel Mikhailovich Tretyakov bought the painting for 100 rubles. Tretyakov continued to purchase Levitan's works and eventually acquired 20 additional paintings (See also Tretyakov Gallery).[2]

Savrasov, who was influenced by painters in the Barbizon school, such as Camille Corot, took students outside to paint en plein air. Previously, the Russian countryside had been considered too uninteresting for painting, but for Levitan landscapes became the center of his work. Savrasov taught Levitan to paint details in his landscapes and to bring his emotions into his works.[3] But by 1883 Levitan had grown discouraged with the Moscow School of Painting and decided to enter a landscape painting in the hopes of winning a silver medal which would qualify him to be a classed artist. Levitan showed the painting to Savrasov, who had been drinking heavily and had stopped teaching at the school; Savrasov wrote "silver medal" on the back of the canvas. The school rejected the painting, and Levitan stopped attending classes.[4] One possible explanation for why the school snubbed one of its best students was because the disgraced Savrasov had commented on the back of the canvas.[5][6] Korovin repeated gossip that antisemitism played a part in the rejection. The Soviet writer, Konstantin Paustovsky, repeated the contention that some thought a Jew should not be painting the Russian countryside.[6][7]

In the spring of 1884 Levitan participated in the mobile art exhibition by the group known as the Peredvizhniki and in 1891 became a member of the Peredvizhniki partnership. During his study in the Moscow School of painting, sculpting and architecture, Levitan befriended Konstantin Korovin, Mikhail Nesterov, architect Fyodor Shekhtel, and the painter Nikolay Chekhov. Levitan often visited Chekhov and some think Levitan was in love with his sister, Maria Pavlovna Chekhova.[citation needed]

In the early 1880s Levitan collaborated with the Chekhov brothers on the illustrated magazine Moscow and illustrated the M. Fabritsius edition Kremlin. Together with Korovin in 1885-1886 he painted scenery for performances of the Private Russian opera of Savva Mamontov, a railroad baron and art patron, who developed an artists' colony 37 miles from Moscow. In his memoir, Polenov wrote that when the curtain rose for the underwater scene Levitan painted with Victor Vasnetsov for the opera Rusalka the audience applauded.[8]

In the 1880s he participated in the drawing and watercolor gatherings at Polenov's house.[9]

Friendship with Anton Chekhov edit

By the mid-1880s Levitan's friendship with Chekhov had deepened, and Levitan began spending time with the Chekhov family near Babkino where the Chekhovs had a house. During his first summer there he painted The River Istra (1885) and gave it to Chekhov. He also painted Twilight River Istra (1885) with a darker, more somber palette. Chekhov was fond of creating pantomimes for his guests, with Levitan often ridiculed for playing the villain, the victim and the alien Jew, ostensibly all in jest.[10]

In 1892 Levitan had a falling out with Chekhov over The Grasshopper, a story Chekhov published in the "Sever" (North) magazine, which Levitan believed was based on his romantic relationship with Sofia Kuvshinnikova. Although Chekhov apologized the two remained estranged until January 1895.[11]

The landscape of mood edit

Levitan's work was a profound response to the lyrical charm of the Russian landscape. Levitan did not paint urban landscapes; with the exception of the View of Simonov Monastery (whereabouts unknown), mentioned by Nesterov, the city of Moscow appears only in the painting Illumination of the Kremlin. During the late 1870s he often worked in the vicinity of Moscow, and created the special variant of the "landscape of mood", in which the shape and condition of nature are spiritualized, and become carriers of conditions of the human soul (Autumn Day. Sokolniki, 1879). During work in Ostankino, he painted fragments of the mansion’s house and park, but he was most fond of poetic places in the forest or modest countryside. Characteristic of his work is a hushed and nearly melancholic reverie amidst pastoral landscapes largely devoid of human presence. Fine examples of these qualities include Vladimirka, (1892), Evening Bells, (1892), and Eternal Rest, (1894), all in the Tretyakov Gallery. Though his late work displayed familiarity with Impressionism, his palette was generally muted, and his tendencies were more naturalistic and poetic than optical or scientific.[citation needed]

Birch trees, which grow freely in central Russia and are considered a national emblem of spring and renewal,[12] were a common motif in Levitan's work, which he painted in various seasons. In Spring Flood (1897) the thin curved white trunks, devoid of foliage, are reflected in the floodwaters left by the melting snows from nearby mountains. Birch Grove (1885–89), another spring scene, with dappled sunlight and low viewpoint, was painted in an Impressionist style. Golden Autumn (1895) shows a grove of autumn birches with orange and yellow foliage beneath a cloud streaked sky which is reflected in a dark blue river winding up from the lower right of the frame. In‘’September Day’’ (1890s) the group of trees with bright yellow foliage is engulfed with wind, the ground is covered with already rotten leaves, one of the characteristic examples of the influence of Impressionism on artist. Levitan painted not only the trees, but the light itself illuminating them, and this was most evident in a painting such as Moonlit Night: Main Road (1897) where two row of birches line a straight road in moonlight. The white trunks shine through the moonlight against the darkening leaves and fields. His ability to capture the various qualities of light has been compared to Claude Monet, but it is unlikely that he used Monet's work as a model for his own.[13]

Later life edit

In the summer of 1890 Levitan went to Yuryevets (Юрьевец) and among numerous landscapes and etudes he painted The View of Krivooserski monastery. So the plan of one of his best pictures, A Quiet Monastery, was born. The image of a silent Monastery and planked bridges over the river, connecting it with the outside world, expressed the artist's spiritual reflections. It is known that this picture made a strong impression on Chekhov.[14] By 1891 Levitan was a member of the Association of Itinerant (or roving) Exhibitions, whose mission was to create a democratic art that was accessible to as many ordinary people as possible, but unlike many of his fellow artists who sought to deliver a message about the hard life of the Russian people, Levitan sought simply to paint beauty. Levitan eventually contributed to exhibitions by the World of Art group, a younger generation of artists who believed beauty as the goal of art.[15]

In September 1892 Jews were again expelled from Moscow and Levitan left the city for Boldino. His friends' pleadings enabled him to return by December of that year.[11]

In 1897, already world-famous, he was elected to the Imperial Academy of Arts and in 1898 he was named the head of the Landscape Studio at his alma mater.[citation needed]

Levitan spent the last year of his life at Chekhov's home in Crimea. In spite of the effects of a terminal illness (he suffered from a heart condition for much of his life), his last works are increasingly filled with light. They reflect tranquility and the eternal beauty of Russian nature.[citation needed]

He was buried in Dorogomilovo Jewish cemetery. In April 1941 Levitan's remains were moved to the Novodevichy Cemetery, next to Chekhov's necropolis. Levitan did not have a family or children.

In the 1890s, he had an on-again, off-again affair with an older married woman; the painter Sofia Kuvshinnikova, which led to a small scandal — and a play by Anton Chekhov ("The Grasshopper") and a threatened duel with the playwright. Chekhov published the story in Sevyer (North), in January 1892.[16] The story concerns a lecherous man who has an affair with a married woman, whose husband dies of an accident (that may have been suicide) after she leaves him. Levitan and Kuvshinnikova were both offended although the central figure in the story was a young wife and Kuvshinnikova was 42. Moreover, she was dark haired and a talented painter, whereas Chekhov's character was blonde and not an artist. The stronger similarity was that her husband was tolerant of her disloyalty to him, as was "The Grasshopper" who forgave his wife's indiscretions.[17] She, Levitan and her husband travelled together and were considered a ménage à trois.[18]

Isaac Levitan's hugely influential art heritage consists of more than a thousand paintings, among them watercolors, pastels, graphics, and illustrations.[citation needed]

Legacy edit

During the year after his death an exhibit of several hundred Levitan paintings was shown in Moscow and then in St. Petersburg. His works appeared on the covers of Russian language textbooks and school children learned of his love for his native land.[19]

A minor planet 3566 Levitan, discovered by Soviet astronomer Lyudmila Zhuravlyova in 1979 is named after him.[20]

Gallery edit

-

Sunny Day (1876)

-

Autumn Landscape (1880)

-

Savvinskaya sloboda near Zvenigorod (1884)

-

Bridge. Savvinskaya sloboda

-

Birch Forest (1885-1889)

-

Spring, High Water

-

Evening Bells (1892)

-

Vladimirka, 1892

-

Over Eternal Peace (1894)

-

Fresh Wind. Volga (1891–1895)

-

March (1895)

-

Golden Autumn (1895)

-

Cloudy Day. (1895)

-

Water lilies (1895)

-

Silence (1898)

-

Plyos (1889)

-

Spring in Italy (1890)

-

Dusk (1900)

-

A Quiet Monastery (1890)

See also edit

Notes edit

References edit

- ^ a b Gregory, Serge (2015). Antosha & Levitasha. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-87580-731-7.

- ^ Gregory, Serge (2015). Antosha & Levitasha. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-87580-731-7.

- ^ Gregory, Serge (2015). Antosha & Levitasha. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-87580-731-7.

- ^ Gregory, Serge (2015). Antosha & Levitasha. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-0-87580-731-7.

- ^ "Levitan | Isaac Levitan". Musings on Art. 27 March 2015. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ^ a b Gregory, Serge (2015). Antosha & Levitasha. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-87580-731-7.

- ^ "The artist beside himself: 1901: Isaac Levitan gains posthumous acclaim.(russian calendar)(Calendar) - Library Search". librarysearch.temple.edu. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ^ Gregory, Serge (2015). Antosha & Levitasha. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-87580-731-7.

- ^ Fiodorov-Davydov, Alexei: "Levitan", page 166-7. Aurora Art Publishers, 1988.

- ^ Gregory, Serge (2015). Antosha & Levitasha. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-87580-731-7.

- ^ a b Chizhmak, Margarita (2010). "Isaac Levitan's Life and Work Timeline". Heritage. 28: 3 – via JSTOR.

- ^ "Birch Tree as a Symbol of Russia :: Manners, Customs and Traditions :: Culture & Arts :: Russia-InfoCentre". russia-ic.com. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ King, Averil (2004). "Levitan and the Silver Birch". Apollo. 160: 46–51.

- ^ "Isaac Levitan. Quiet Abode. The description of a picture. Masterpieces of Russian painting | Русские художники. Russian Artists". www.tanais.info. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ^ Eidelman, Tamara (2011). "The Artist Beside Himself". Russian Life. 54 (2): 17–19 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Muratova, K. D. Commentaries to Попрыгунья. The Works by A.P. Chekhov in 12 volumes. Khudozhestvennaya Literatura. Moscow, 1960. Vol. 7, pp. 516-517

- ^ Donald Rayfield (1998). Anton Chekhov: A Life. Northwestern University Press. pp. 269–. ISBN 978-0-8101-1795-2.

- ^ Donald Rayfield (1998). Anton Chekhov: A Life. Northwestern University Press. pp. 221–225. ISBN 978-0-8101-1795-2.

- ^ Eidelman, Tamara (2011). "The Artist Beside Himself". Russian Life. 54 (2): 17–19. ProQuest 854588961.

- ^ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. p. 300. ISBN 3-540-00238-3.

Sources edit

- A. A. Fyodorov-Davidov: Levitan, Aurora Art Publishers, Leningrad, 1981

- A. King: Isaak Levitan. Lyrical Landscape, Philipp Wilson Publishers Ltd., London, 2006

- L. Mehulic: Isaac Ilych Levitan and Evening Bells from The Mimara Museum, Muzej Mimara, Zagreb, 2009