The internal anal sphincter, IAS, or sphincter ani internus is a ring of smooth muscle that surrounds about 2.5–4.0 cm of the anal canal. It is about 5 mm thick, and is formed by an aggregation of the smooth (involuntary) circular muscle fibers of the rectum. It terminates distally about 6 mm from the anal orifice.[citation needed]

| Internal anal sphincter | |

|---|---|

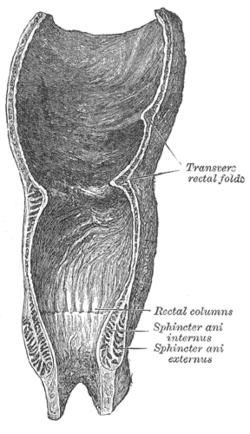

Coronal section through the anal canal. B. Cavity of urinary bladder V.D. Vas deferens. S.V. Seminal vesicle. R. Second part of rectum. A.C. Anal canal. L.A. Levator ani. I.S. Internal anal sphincter. E.S. External anal sphincter. | |

Coronal section of rectum and anal canal | |

| Details | |

| Nerve | Pelvic splanchnic nerves (S4), thoracicolumbar outflow of the spinal cord |

| Actions | Keeps the anal canal and orifice closed, aids in the expulsion of the feces |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | musculus sphincter ani internus |

| TA98 | A05.7.05.011 |

| TA2 | 3018 |

| FMA | 15710 |

| Anatomical terms of muscle | |

The internal anal sphincter aids the sphincter ani externus to occlude the anal aperture and aids in the expulsion of the feces. Its action is entirely involuntary. It is normally in a state of continuous maximal contraction to prevent leakage of faeces or gases. Sympathetic stimulation stimulates and maintains the sphincter's contraction, and parasympathetic stimulation inhibits it. It becomes relaxed in response to distention of the rectal ampulla, requiring voluntary contraction of the puborectalis and external anal sphincter to maintain continence,[1] and also contracts during the bulbospongiosus reflex.[2][3][4][5]

Structure

editThe internal anal sphincter is the specialised thickened terminal portion of the inner circular layer of smooth muscle of the large intestine. It extends from the pectinate line (anorectal junction) proximally to just proximal to the anal orifice distally (the distal termination is palpable). Its muscle fibres are arranged in a spiral (rather than a circular) manner.[6]

At its distal extremity, it is in contact with but separate from the external anal sphincter.[citation needed]

Innervation

editThe sphincter receives extrinsic autonomic innervation via the inferior hypogastric plexus, with sympathetic innervation derived from spinal levels L1-L2, and parasympathetic innervation derived from S2-S4.[6]

The internal anal sphincter is not innervated by the pudendal nerve (which provides motor and sensory innervation to the external anal sphincter).[7]

Function

editThe sphincter is contracted in its resting state, but reflexively relaxes in certain contexts (most notably during defecation).[6]

Transient relaxation of its proximal portion occurs with rectal distension and post-prandial rectal contraction (the recto-anal inhibitory reflex and sampling reflex, respectively) while the distal portion of the sphincter remains contracted and the external anal sphincter becomes contracted to maintain continence; this transient relaxation allows passage of stool into the proximal anal canal - this filling is sensed.[6]

Continence

editThe IAS contributes 55% of the resting pressure of the anal canal. It is very important for bowel continence, especially for liquid and gas. When the rectum fills beyond a certain capacity, the rectal walls are distended, triggering the defecation cycle. This begins with the rectoanal inhibitory reflex (RAIR), where the IAS relaxes. This is thought to allow a small amount of rectal contents to descend into the anal canal where specialized mucosa samples whether it is gas, liquid or solid. Problems with the IAS often present as degrees of fecal incontinence (especially partial incontinence to liquid) or mucous rectal discharge.[8]

Physiology

editNeurophysiology

editSympathetic stimulation is mediated by alpha-2 adrenergic receptors and results in contraction of the sphincter.[6]

Parasympathetic stimulation is mediated by muscarinic acetylcholine receptors and results in relaxation of the sphincter.[6]

Nitrergic stimulation also produces relaxation which has pharmacological significance.[6]

Clinical significance

editClinical pharmacology

editNitrergic pharmaceutical agents produce relaxation of the muscular tone of the sphincter and are applicable in pathological contexts where this tone is abnormally increased.[6]

Regenerative medicine

editIn 2011, it was announced by the Wake Forest School of Medicine that the first bioengineered, functional anal sphincters had been constructed in a laboratory made from muscle and nerve cells, providing a proposed solution for anal incontinence.[9][10]

Additional images

edit-

Intestines

-

Anatomy of the human anus

See also

editReferences

editThis article incorporates text in the public domain from page 426 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ Moore, K., Dalley, A., Agur, A. "Clinically Oriented Anatomy. 6th Edition.

- ^ Vodušek DB, Deletis V (2002). "Intraoperative Neurophysiological Monitoring of the Sacral Nervous System". Neurophysiology in Neurosurgery, A Modern Intraoperative Approach: 153–165. doi:10.1016/B978-012209036-3/50011-1. ISBN 9780122090363. S2CID 78605592.

- ^ Sarica Y, Karacan I (July 1987). "Bulbocavernosus reflex to somatic and visceral nerve stimulation in normal subjects and in diabetics with erectile impotence". The Journal of Urology. 138 (1): 55–58. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(17)42987-9. PMID 3599220.

- ^ Jiang XZ, Zhou CK, Guo LH, Chen J, Wang HQ, Zhang DQ, et al. (December 2009). "[Role of bulbocavernosus reflex to stimulation of prostatic urethra in pathologic mechanism of primary premature ejaculation]". Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (in Chinese). 89 (46): 3249–3252. PMID 20193361.

- ^ Podnar S (February 2012). "Clinical elicitation of the penilo-cavernosus reflex in circumcised men". BJU International. 109 (4): 582–585. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10364.x. PMID 21883821. S2CID 27143105.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Standring, Susan (1201). Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice (42th ed.). New York. p. 683. ISBN 978-0-7020-7707-4. OCLC 1201341621.

- ^ "Chapter 36: The rectum and anal canal". Archived from the original on 2012-05-04. Retrieved 2011-07-12.

- ^ David E. Beck, Patricia L. Roberts, Theodore J. Saclarides, Anthony J. Senagore, Michael J. Stamos, Steven D. Wexner (Editors) (2007). The ASCRS textbook of colon and rectal surgery. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-24846-2.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Human cells engineered to make functional anal sphincters in lab", Science Daily. August 10, 2011. Retrieved 3 feb 2017

- ^ "Anal Sphincters" Archived 2018-05-23 at the Wayback Machine, Wake Forest School of Medicine. December 12, 2015. Retrieved 3 feb 2017