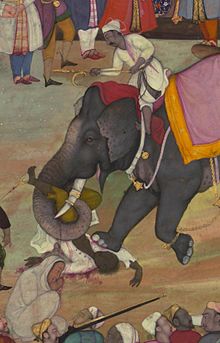

Execution by elephant, or Gunga Rao, was a method of capital punishment in South and Southeast Asia, particularly in India, where Asian elephants were used to crush, dismember, or torture captives during public executions. The animals were trained to kill victims immediately or to torture them slowly over a prolonged period. Most commonly employed by royalty, the elephants were used to signify both the ruler's power of life and death over his subjects and his ability to control wild animals.[1]

The sight of elephants executing captives was recorded in contemporary journals and accounts of life in Asia by European travellers. The practice was eventually suppressed by the European colonial powers that colonised the region in the 18th and 19th centuries. While primarily confined to Asia, the practice was occasionally used by European and African powers, such as Ancient Rome and Ancient Carthage, particularly to deal with mutinous soldiers.

Cultural aspects edit

Historically, the elephants were under the constant control of a driver or mahout, thus enabling a ruler to grant a last-minute reprieve and display merciful qualities.[1] Several such exercises of mercy are recorded in various Asian kingdoms. The kings of Siam trained their elephants to roll the convicted person "about the ground rather slowly so that he is not badly hurt". The Mughal Emperor Akbar is said to have "used this technique to chastise 'rebels' and then in the end the prisoners, presumably much chastened, were given their lives".[1] On one occasion, Akbar was recorded to have had a man thrown to the elephants to suffer five days of such treatment before pardoning him.[2] Elephants were occasionally used in trial by ordeal in which the condemned prisoner was released if he managed to fend off the elephant.[1]

The use of elephants in such fashion went beyond the common royal power to dispense life and death. Elephants have long been used as symbols of royal authority (and still are in some places, such as Thailand, where white elephants are held in reverence). Their use as instruments of state power sent the message that the ruler was able to preside over very powerful creatures who were under total command. The ruler was thus seen as maintaining a moral and spiritual domination over wild beasts, adding to their authority and mystique among subjects.[1]

Geographical scope edit

Asian powers edit

Southeast Asia edit

Elephants were used for execution in Burma, the Malay Peninsula, and Brunei in the pre-modern period[3][4] as well as in the kingdom of Champa.[5] In Siam, elephants were trained to throw the condemned into the air before trampling them to death.[1] There exists an account in the 1560s of men being trampled to death by elephants in Ayutthaya due to their unruly behaviour.[6] Alexander Hamilton provides the following account from Siam:[7]

For Treason and Murder, the Elephant is the Executioner. The condemned Person is made fast to a Stake driven into the Ground for the Purpose, and the Elephant is brought to view him, and goes twice or thrice round him, and when the Elephant's Keeper speaks to the monstrous Executioner, he twines his Trunk round the Person and Stake, and pulling the Stake from the Ground with great Violence, tosses the Man and the Stake into the Air, and in coming down, receives him on his Teeth, and making him off again, puts one of his fore Feet on the Carcase, and squeezes it flat.

The journal of John Crawfurd records another method of execution by elephant in the kingdom of Cochinchina (modern south Vietnam), where he served as a British envoy in 1821. Crawfurd recalls an event where "the criminal is tied to a stake, and [Excellency's favourite] elephant runs down upon him and crushes him to death."[8]

The use of elephants for execution was reported in Aceh by a French merchant, François Martin. Under the rule of Sultan Alauddin Ri'ayat Syah Sayyid al-Mukammal, an adulterous couple was thrown to the elephant and stomped to death.[9]

South Asia edit

India edit

Hindu and Muslim rulers in India executed tax evaders, rebels and enemy soldiers alike "under the feet of elephants".[1] The Hindu Manu Smriti or Laws of Manu, written sometime between 200 BCE and 200 CE, prescribed execution by elephants for a number of offences. If property was stolen, for instance, "the king should have any thieves caught in connection with its disappearance executed by an elephant."[10] For example, in 1305, the Sultan of Delhi turned the deaths of Mongol prisoners into public entertainment by having them crushed by elephants.[11]

During the Mughal era, "it was a common mode of execution in those days to have the offender trampled underfoot by an elephant."[12] Captain Alexander Hamilton, writing in 1727, described how the Mughal ruler Shah Jahan ordered an offending military commander to be carried "to the Elephant Garden, and there to be executed by an Elephant, which is reckoned to be a shameful and terrible Death".[13] The Mughal Emperor Humayun ordered the crushing by elephant of an imam he mistakenly believed to be critical of his reign.[14] Some monarchs also adopted this form of execution for their own entertainment. The emperor Jahangir, another Mughal emperor, is said to have ordered a huge number of criminals to be crushed for his amusement. The French traveler François Bernier, who witnessed such executions, recorded his dismay at the pleasure that the emperor derived from this cruel punishment.[2] Nor was crushing the only method used by execution elephants; in the pre-Mughal sultanate of Delhi, elephants were trained to slice prisoners to pieces "with pointed blades fitted to their tusks".[1] The Muslim traveler Ibn Battuta, visiting Delhi in the 1330s, has left the following eyewitness account of this particular type of execution by elephants:[15]

Upon a certain day, when I myself was present, some men were brought out who had been accused of having attempted the life of the Vizier. They were ordered, accordingly, to be thrown to the elephants, which had been taught to cut their victims to pieces. Their hoofs were cased with sharp iron instruments, and the extremities of these were like knives. On such occasions the elephant-driver rode upon them: and, when a man was thrown to them, they would wrap the trunk about him and toss him up, then take him with the teeth and throw him between their fore feet upon the breast, and do just as the driver should bid them, and according to the orders of the Emperor. If the order was to cut him to pieces, the elephant would do so with his irons, and then throw the pieces among the assembled multitude: but if the order was to leave him, he would be left lying before the Emperor, until the skin should be taken off, and stuffed with hay, and the flesh given to the dogs.

Other Indian polities also carried out executions by elephant. The Maratha Chatrapati Sambhaji ordered this form of death for a number of conspirators, including the Maratha official Anaji Datto in the late seventeenth century.[16] Another Maratha leader, the general Santaji, inflicted the punishment for breaches in military discipline. The contemporary historian Khafi Khan reported that "for a trifling offense he [Santaji] would cast a man under the feet of an elephant."[17]

The early-19th-century writer Robert Kerr relates how the king of Goa "keeps certain elephants for the execution of malefactors. When one of these is brought forth to dispatch a criminal, if his keeper desires that the offender be destroyed speedily, this vast creature will instantly crush him to atoms under his foot; but if desired to torture him, will break his limbs successively, as men are broken on the wheel."[18] The naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon cited this flexibility of purpose as evidence that elephants were capable of "human reasoning, [rather] than a simple, natural instinct".[19]

Such executions were often held in public as a warning to any who may transgress. To that end, many of the elephants were especially large, often weighing in excess of nine tons. The executions were intended to be, and often were, gruesome. They were sometimes preceded by torture publicly inflicted by the same elephant used for the execution. An account of one such torture-and-execution at Baroda in 1814 has been preserved in The Percy Anecdotes:

The man was a slave, and two days before had murdered his master, brother to a native chieftain, called Ameer Sahib. About eleven o'clock the elephant was brought out, with only the driver on his back, surrounded by natives with bamboos in their hands. The criminal was placed three yards behind on the ground, his legs tied by three ropes, which were fastened to a ring on the right hind leg of the animal. At every step the elephant took, it jerked him forward, and every eight or ten steps must have dislocated another limb, for they were loose and broken when the elephant had proceeded five hundred yards. The man, though covered in mud, showed every sign of life, and seemed to be in the most excruciating torments. After having been tortured in this manner for about an hour, he was taken to the outside of the town, when the elephant, which is instructed for such purposes, was backed, and put his foot on the head of the criminal.[20]

The use of elephants as executioners continued well into the latter half of the 19th century. During an expedition to central India in 1868, Louis Rousselet described the execution of a criminal by an elephant. A sketch depicting the execution showed the condemned being forced to place his head upon a pedestal, and then being held there while an elephant crushed his head underfoot. The sketch was made into a woodcut and printed in "Le Tour du Monde", a widely circulated French journal of travel and adventure, as well as foreign journals such as Harper's Weekly.[21]

The growing power of the British Empire led to the decline and eventual end of elephant executions in India. Writing in 1914, Eleanor Maddock noted that in Kashmir, since the arrival of Europeans, "many of the old customs are disappearing – and one of these is the dreadful custom of the execution of criminals by an elephant trained for the purpose and which was known by the hereditary name of 'Gunga Rao'."[22]

Sri Lanka edit

Elephants were widely used across the Indian subcontinent and South Asia as a method of execution. The English sailor Robert Knox, writing in 1681, described a method of execution by elephant which he had witnessed while being held captive in Sri Lanka. Knox says the elephants he witnessed had their tusks fitted with "sharp Iron with a socket with three edges". After impaling the victim's body with its tusks, the elephant would "then tear it in pieces, and throw it limb from limb".[23]

The 19th-century traveler James Emerson Tennent comments that "a Kandyan [Sri Lankan] chief, who was witness to such scenes, has assured us that the elephant never once applied his tusks, but, placing his foot on the prostrate victim, plucked off his limbs in succession by a sudden movement of his trunk."[24] Knox's book depicts exactly this method of execution in a famous drawing, An Execution by an Eliphant.

Writing in 1850, the British diplomat Henry Charles Sirr described a visit to one of the elephants that had been used by Sri Vikrama Rajasinha, the last king of Kandy, to execute criminals. Crushing by elephant had been abolished by the British after they annexed the Kingdom of Kandy in 1815 but the king's execution elephant was still alive and evidently remembered its former duties. Sirr comments:[25]

During the native dynasty it was the practice to train elephants to put criminals to death by trampling upon them, the creatures being taught to prolong the agony of the wretched sufferers by crushing the limbs, avoiding the vital parts. With the last tyrant king of Candy, this was a favourite mode of execution and as one of the elephant executioners was at the former capital during our sojourn there we were particularly anxious to test the creature's sagacity and memory. The animal was mottled and of enormous size, and was quietly standing there with his keeper seated upon his neck; the noble who accompanied us desired the man to dismount and stand on one side. The chief then gave the word of command, ordering the creature to 'slay the wretch!' The elephant raised his trunk, and twined it, as if around a human being; the creature then made motions as if he were depositing the man on the earth before him, then slowly raised his back foot, placing it alternately upon the spots where the limbs of the sufferer would have been. This he continued to do for some minutes; then, as if satisfied that the bones must be crushed, the elephant raised his trunk high upon his head and stood motionless; the chief then ordered him to 'complete his work,' and the creature immediately placed one foot, as if upon the man's abdomen, and the other upon his head, apparently using his entire strength to crush and terminate the wretch's misery.

West Asia edit

During the medieval period, executions by elephants were used by several West Asian imperial powers, including the Byzantine, Sassanid, Seljuq, and Timurid empires.[1] When the Sassanid king Khosrau II, who had a harem of 3,000 wives and 12,000 female slaves, demanded as a wife Hadiqah, the daughter of the Christian Arab Na'aman, Na'aman refused to permit his Christian daughter to enter the harem of a Zoroastrian; for this refusal, he was trampled to death by an elephant.

The practice appears to have been adopted in parts of the Muslim Middle East. Rabbi Petachiah of Ratisbon, a 12th-century Jewish traveler, reported an execution by this means during his stay in Seljuk-ruled northern Mesopotamia (modern Iraq):[26]

At Nineveh there was an elephant. Its head is not protruding. It is big, eats about two wagon loads of straw at once; its mouth is in its breast, and when it wants to eat it protrudes its lip about two cubits, takes up the straw with it, and puts it in its mouth. When the sultan condemns anyone to death, they say to the elephant, "this person is guilty." It then seizes him with its lip, casts him aloft and slays him.

Europe edit

Perdiccas, who became regent of Macedon on the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC, had mutineers from the faction of Meleager thrown to the elephants to be crushed in the city of Babylon.[28] The Roman writer Quintus Curtius Rufus relates the story in his Historiae Alexandri Magni:[29][30]

Perdiccas saw that they [the mutineers] were paralyzed and at his mercy. He withdrew from the main body some 300 men who had followed Meleager at the time when he burst from the first meeting held after Alexander's death, and before the eyes of the entire army he threw them to the elephants. All were trampled to death beneath the feet of the beasts...

Similarly, the Roman writer Valerius Maximus records how the general Lucius Aemilius Paulus Macedonicus "after King Perseus was vanquished [in 167 BC], for the same fault (desertion) threw men under elephants to be trampled ... And indeed military discipline needs this kind of severe and abrupt punishment, because this is how strength of arms stands firm, which, when it falls away from the right course, will be subverted."[31]

Africa edit

In 240 BC, a Carthaginian army led by Hamilcar Barca was fighting a coalition of mutinous soldiers and rebellious African cities led by Spendius. After losing a battle when a force of Numidian cavalry deserted to the Carthaginians, Spendius had 700 Carthaginian prisoners tortured to death. From this point, prisoners taken by the Carthaginians were trampled to death by their war elephants.[32][33] This unusual ferocity caused the conflict to be termed the "Truceless War".[34][35]

There are fewer records of elephants being used as straightforward executioners for the civil population. One such example is mentioned by Josephus and the deuterocanonical book of 3 Maccabees in connection with the Egyptian Jews, though the story is likely apocryphal.[36] 3 Maccabees describes an attempt by Ptolemy IV Philopator (ruled 221–204 BC) to enslave and brand Egypt's Jews with the symbol of Dionysus. When the majority of the Jews resisted, the king is said to have rounded them up and ordered them to be trampled on by elephants.[37][36] The mass execution was ultimately thwarted, supposedly by the intervention of angels, following which Ptolemy took an altogether more forgiving attitude towards his Jewish subjects.[38][36]

References edit

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Thomas T. Allsen (3 Jun 2011). The Royal Hunt in Eurasian History. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0812201079.

- ^ a b Annemarie Schimmel (2004). The Empire of the Great Mughals: History, Art and Culture. Reaktion Books. p. 96. ISBN 9781861891853.

- ^ Norman Chevers (1856). A Manual of Medical Jurisprudence for Bengal and the North-western Provinces. Carbery. pp. 260–261.

- ^ Reid, Anthony (1988). Southeast Asia in the age of commerce, 1450–1680, Volume One. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Yale University Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-300-03921-4.

- ^ Schafer, Edward H. "The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Study of T'ang Exotics". University of California Press, 1985. p. 80. ASIN: B0000CLTET

- ^ Reid, Anthony (1988). Southeast Asia in the age of commerce, 1450–1680, Volume Two. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Yale University Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-300-03921-4.

- ^ Hamilton, Alexander (1727). A new account of the East Indies. Vol. 2. Edinburgh: John Mosman. pp. 181–182.

- ^ Crawfurd, John. "Journal of an Embassy from the Governor-general of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China". H. Colburn and R. Bentley, 1830. p. 419.

- ^ Hanggoro, Hendaru Tri (7 March 2012). "Hukuman Kejam dari Sultan". historia.id. Historia. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ^ Manu (2004). The Law Code of Manu. Translated by Patrick Olivelle. Oxford University Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-19-280271-2.

- ^ Jack Weatherford-Genghis Khan, p.116

- ^ Natesan, G.A. The Indian Review, p. 160

- ^ Hamilton, p. 170.

- ^ Eraly, p. 45.

- ^ Battuta, "The travels of Ibn Battuta", transl. Lee, S, London 1829, pp. 146-47

- ^ Eraly, p. 479.

- ^ Eraly, p. 498

- ^ Kerr, p. 395.

- ^ Buffon, Georges Louis Leclerc. "Natural history of man, the globe, and of quadrupeds". vol. 1. Leavitt & Allen, 1857. p. 113.

- ^ Ryley Scott, George. "The Percy Anecdotes vol. VIII". The History of Torture Throughout the Ages. Torchstream Books, 1940. pp. 116–7.

- ^ Harper's Weekly, February 3, 1872

- ^ Maddock, Eleanor. "What the Crystal Revealed". American Theosophist Magazine, April to September 1914. p. 859.

- ^ Knox, Robert. "An Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon". London, 1681.

- ^ Tennent, p. 281.

- ^ Sirr, Sir Charles Henry, quoted in Barrow, George. "Ceylon: Past and Present". John Murray, 1857. pp. 135–6.

- ^ Benisch, A. (trans). "Travels of Petachia of Ratisbon". London, 1856.

- ^ Nasuh, Matrakci (1588). "Execution of Prisoners, Belgrade". Süleymanname, Topkapi Sarai Museum, Ms Hazine 1517.

- ^ Fox, Robin Lane. "Alexander the Great". Penguin, 2004. p. 474. ISBN 0-14-008878-4

- ^ Quintus Curtius Rufus. Historia Alexandri Magni Liber X (in Latin) – via Wikisource.

- ^ "Curt. 10.6-10". Archived from the original on January 3, 2006.

- ^ Futrell, Alison (Quoted by) (ed.). "A Sourcebook on the Roman Games". Blackwell Publishing, 2006. p. 8.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 210.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 135.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 208.

- ^ Eckstein 2017, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Collins, p. 122.

- ^ 3 Maccabees 5

- ^ 3 Maccabees 6

Sources edit

- Allsen, Thomas T. "The Royal Hunt in Eurasian History". University of Pennsylvania Press, May 2006. ISBN 0-8122-3926-1

- Chevers, Norman. "A Manual of Medical Jurisprudence for Bengal and the Northwestern Provinces". Carbery, 1856.

- Collins, John Joseph. "Between Athens and Jerusalem: Jewish Identity in the Hellenistic Diaspora". Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, October 1999. ISBN 0-8028-4372-7

- Eckstein, Arthur (2017). "The First Punic War and After, 264-237BC". The Encyclopedia of Ancient Battles. Wiley Online Library. pp. 1–14. doi:10.1002/9781119099000.wbabat0270. ISBN 9781405186452.

- Eraly, Abraham. "Mughal Throne: The Saga of India's Great Emperors", Phoenix House, 2005. ISBN 0-7538-1758-6

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2006). The Fall of Carthage: The Punic Wars 265–146 BC. London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-304-36642-2.

- Hamilton, Alexander. "A New Account of the East Indies: Being the Observations and Remarks of Capt. Alexander Hamilton, from the Year 1688 to 1723". C. Hitch and A. Millar, 1744.

- Kerr, Robert. "A General History and Collection of Voyages and Travels". W. Blackwood, 1811.

- Lee, Samuel (trans). "The Travels of Ibn Batuta". Oriental Translation Committee, 1829.

- Miles, Richard (2011). Carthage Must be Destroyed. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-141-01809-6.

- Olivelle, Patrick (trans). "The Law Code of Manu". Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-19-280271-2

- Schimmel, Annemarie. "The Empire of the Great Mughals: History, Art and Culture". Reaktion Books, February 2004. ISBN 1-86189-185-7

- Tennent, Emerson James. "Ceylon: An Account of the Island Physical, Historical and Topographical". Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts, 1860.