Eosimias is a genus of early primates, first discovered and identified in 1999 from fossils collected in the Shanghuang fissure-fillings of Liyang, the southern city of Jiangsu Province, China. It is a part of the family Eosimiidae, and includes three known species: Eosimias sinensis, Eosimias centennicus, and Eosimias dawsonae.[3] It provides us with a glimpse of a primate skeleton similar to that of the common ancestor of the Haplorhini (including all simians). The name Eosimias is designed to mean "dawn monkey", from Greek eos "dawn" and Latin simius "monkey".[4]

| Eosimias | |

|---|---|

| |

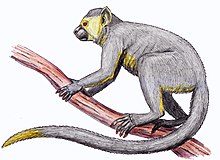

| Restoration of E. sinensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | †Eosimiidae |

| Genus: | †Eosimias Beard et al., 1994 |

| Species[1] | |

| |

Dating has proven this genus lived from 45 to 40 million years ago in the middle Eocene.[4] The genus Eosimias is unique because of the presence of primitive and derived traits. It provides new insight into the phylogenetic relationships between simians and prosimians (especially the phylogenetic position of the haplorhine prosimian tarsiers). It can best be described as a likely tree dweller that relied on a steady diet of insects and nectar.

Most eosimiid species are documented by unique or fragmentary specimens. This, as well as the strong belief that simians originated in Africa has made it difficult for many[who?] to accept the idea that Asia played a role in early primate evolution. Although some continue to challenge the anthropoid resemblances found in Eosiimidae, extensive anatomical evidence collected over the past decade substantiates its anthropoid status.[citation needed]

Eosimias sinensis

editEosimias sinensis (Chinese: 中华曙猿, lit. 'dawn monkey of China') was first discovered in China in 1992 by Christopher Beard. It was found in a mountain near Liyang City, Jiangsu province, China.

The species is believed to have lived 45 million years before present, in the Eocene epoch.[5] E. sinensis was tiny, as small as the smallest monkey presently, the pygmy marmoset (Cebuella pygmaea) of South America, and could fit in the palm of a human's hand.[6] Its teeth are considered more primitive than those of early higher primates known from Africa, including Algeripithecus. Due to its highly primitive nature, some paleontologists consider E. sinensis to be evidence that higher primates may have originated in Asia rather than Africa.[5]

Christopher Beard was the lead member of the team that discovered Eosimias sinensis in 1994. Beard recovered a right mandible, cataloged as IVPP V10591, which preserved P4–M2 and roots or alveoli for C1, P2–3, and M3. Although it retains primitive characters such as a small body size (mean estimates range from 67–137 grams (2.4–4.8 oz)) and an unfused mandibular symphysis, it appears to be a primitive simian based on its dental characteristics, including a lower dental formula of 2.1.3.3.[4] Eosimias sinensis has incisors which are vertical and spatulate. These creatures are known primarily from lower jaws and teeth, no cranial remains have been able to indicate whether Eosimias was diurnal or nocturnal.[7]

Eosimias centennicus

editEosimias centennicus was found in 1995 while doing fieldwork in the Yuanqu Basin of the southern Shanxi Province in China.[8] Among these recovered fossils is the first complete lower dentition of Eosimias, catalogued as IVPP V11000. All anatomical information yielded from these fossils confirms the anthropoid-like traits found in E. sinensis. Biostratigraphic evidence also suggests these fossils are younger than E. sinensis, which is consistent with the anatomy of eosiimids because the dentition of E. centennicus is slightly more derived than that of E. sinensis.[8] This species was also found to be a very tiny primate, with mean estimates of body mass ranging from 91 to 179 grams (3.2 to 6.3 oz). E. sinesis was originally described on the basis of fragmentary fossils, but with the discovery of E. centennicus and a complete lower dentition, Eosimias can more definitively be described as an early anthropoid.

Eosimias dawsonae

editEosimias dawsonae is the newest of the Eosimias species. It is categorized by the type specimen IVPP V11999, which includes a left dentary fragment and roots of the alveoli. It was collected by Christopher Beard in 1995.[9] Analysis of these remains has led to the conclusion it was the largest of the known species of Eosimias, yielding a body mass ranging from 107 to 276 grams (3.8 to 9.7 oz). Stratigraphic evidence also shows E. dawsonae is older than E. centennicus.

Unidentified fossils

editAdditionally, an expedition team discovered evidence of a new, small eosimiid from Myanmar in 1999. The new specimen, represented by a right heel bone cataloged as NMMP 23, was found in wash residue in the Pondaung Formation.[10] This specimen is very morphologically similar to the Eosimias discovered in the Shanghuang region of China. The best estimate for NMMP 23 includes an overall mean weight of about 111 grams, which places it in the upper-sized end of Eosimias fossils discovered. The presence of eosimiid in Myanmar, as well as a high species diversity found in China leads to an apparent conclusion that they had a relatively wide distribution.[10]

Eosimias paukkaungensis

editA new species of eosimiid primate, Eosimias paukkaungensis, from the latest middle Eocene of Pondaung, central Myanmar, was discovered in the early 2000s. The specimen consists of left and right mandibular fragments preserving only the M3, so that its generic status is provisional. The E. paukkaungensis fossil is much larger than homologues of the two Eosimias species from China.[2]

References

edit- ^ a b "Eosimias". paleobiodb.org. Retrieved 2021-07-28.

- ^ a b Takai, Masanaru; Sein, Chit; Tsubamoto, Takehisa; Egi, Naoko; Maung, Maung; Shigehara, Nobuo (2005). "A new eosimiid from the latest middle Eocene in Pondaung, central Myanmar". Anthropological Science. 113 (1): 17–25. doi:10.1537/ase.04S003.

- ^ Beard, K.C.; Qi, T.; Dawson, M.R.; Wang, B. & Li, C. (1994). "A diverse new primate fauna from middle Eocene fissure-fillings in southeastern China". Nature. 368 (6472): 604–609. Bibcode:1994Natur.368..604B. doi:10.1038/368604a0. PMID 8145845. S2CID 2471330.

- ^ a b c "Tracking Our Extended Family". Carnegie Mellon’s Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on July 6, 2010. Retrieved 2010-08-09.

- ^ a b "The Discovery of Eosimias sinensis, the Ancestor of the Human and Their Anthropoid Relative" (in Chinese). Chinese Academy of Sciences. 2002-02-20. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2010-08-09.

- ^ Hendricks, M. (April 2001). "Tales from the Crust". Johns Hopkins Magazine. Retrieved 2010-08-09.

- ^ John G. Fleagle, Primate Adaptation & Evolution, ch. 10

- ^ a b Gebo, D.L.; Gunnell, G.F.; Ciochon, R.L.; Takai, M.; Tsubamato, T. & Egi, N. (2002). "New eosimiid primate from Myanmar". Journal of Human Evolution. 43 (4): 549–553. Bibcode:2002JHumE..43..549G. doi:10.1006/jhev.2002.0571.

- ^ Beard, K.C.; Tong, Y.; Dawson, M.R.; Wang, J. & Huang, X. (1996). "Earliest complete dentition of an anthropoid primate from the late middle Eocene of Shanxi Province, China". Science. 272 (5258): 82–85. Bibcode:1996Sci...272...82B. doi:10.1126/science.272.5258.82. S2CID 83617771.

- ^ a b Beard, K. C.; Wang, J. (2004). "The eosimiid primates (Anthropoidea) of the Heti Formation, Yuanqu Basin, Shanxi and Henan Provinces, People's Republic of China". Journal of Human Evolution. 46 (4): 401–432. Bibcode:2004JHumE..46..401B. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.01.002. PMID 15066378.