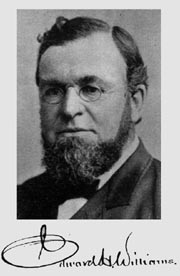

Edward Higginson Williams[1] (June 1, 1824 – December 21, 1899) was an American physician and railroad executive known for his philanthropy.

Dr. Edward H. Williams | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | June 1, 1824 |

| Died | December 21, 1899 (aged 75) |

| Education | Vermont Medical College Woodstock |

| Occupation(s) | Physician, railroad executive |

Early life and medical career

editWilliams was born on June 1, 1824, in Woodstock, Vermont to Vermont Secretary of State Norman Williams and Mary Ann Wentworth (Brown) Williams.[1] He graduated from Vermont Medical College in Woodstock[2] and worked for a time as a physician. While working on the Rutland & Burlington railroad in Cavendish, Vermont, with his former physics teacher Hosea Doton,[3] he was the first physician to treat railroad contractor Phineas Gage after Gage survived accidentally blasting a tamping iron through his jaw and skull while setting an explosive charge.[4] This event occurred three months after his marriage to Cornelia Bailey Pratt in Woodstock June 15, 1848.[5] A year later they were still in Proctorville, near Cavendish and about 20 miles south of Woodstock when their son Edward H. Williams Jr. was born.[6] By 1850, Edward, Cornelia and their new son had settled in Northfield, Vermont. There he began practicing medicine with his brother-in-law, Dr. Samuel White Thayer, who had graduated from the same medical college in Woodstock and had married Cornelia's sister Sarah in 1841.[7] Together Williams and Thayer were civically active in the village of Northfield forming an Odd Fellows lodge and establishing a new Episcopal Church congregation in 1851.[8]

Railroad executive

editDuring the rest of the 1850s decade Dr. Williams transitioned from medicine to civil engineering railroads. While in Northfield he became close friends with Isaac B Howe and John C. Gault, engineers with the Vermont Central & Canada railroad.[9][10] At that time the town of Northfield had become a key hub for Charles Paine's Vermont Central and its Canadian connections. Dr. Williams was working in superintending roles with the Caughnawaga in Canada, the Michigan Southern and finally the Milwaukee & Mississippi in 1858. In 1859 he went west to assume Assistant Superintendent of the Galena & Chicago Union railroad in Chicago.[11] This temporarily split up the three friends as Williams took Gault with him to Chicago while Howe stayed in Northfield to get married and tie up a number of business dealings.[12]

The Galena was building west from Chicago with plans to connect with the Chicago Iowa & Nebraska railroad's Mississippi bridge at Clinton Iowa. This would then allow connection with the Cedar Rapids & Missouri River building across Iowa to connect with the Transcontinental Railroad in Council Bluffs opposite Omaha on the Missouri River. [13] By 1861 Howe was brought to Clinton to take over control of the Iowa roads and the following year the CI&N and CR&MR railroads were leased by the Galena completing the plan. Dr. Williams was Asst. to Supt. E.B. Talcott and John Gault was Master of Transportation while I.B. Howe was Supt. of the Iowa Roads.[14]

For the next few years the war of the rebellion caused delays in railroad construction unless it was related to the war. In July 1864 a grand consolidation took place where a small and little-known Chicago & Northwestern railroad was organized to assume control of the Galena in Illinois as well as its leased roads in Iowa, including the Mississippi bridge and ferry at Clinton, and a lucrative charter to Council Bluffs. Dr. Williams was now Superintendent of the Galena Division with Gault as his assistant and IB Howe was Superintendent of the Iowa Division including the leased Chicago Iowa & Nebraska and Cedar Rapids & Missouri River roads.[15] The C&NW continued on to join with the Union Pacific's transcontinental railroad in Omaha by 1867, but by that famous moment in history Dr. Williams had moved on in 1865 to another prestigious job – Assistant Superintendent and then Superintendent of the Pennsylvania Railroad.[16]

In 1870 Dr. Williams departed his very prestigious superintendency of the Pennsylvania Railroad to become a partner in the firm of Burnham, Parry, Williams, & company, the owners of the Baldwin Locomotive Works in Philadelphia. In this capacity he traveled the globe evaluating and assisting companies and countries with their locomotive and railroad needs and enhancing and improving on the already respected design and reputation of Baldwin locomotives.[17]

Philanthropy

editWilliams gave prominently towards education. He constructed and equipped buildings for the teaching of science at Carleton College (dedicated in memory of his son William) and the University of Vermont (in memory of his wife). He also made large donations to the University of Pennsylvania and other educational institutions.[1] Williams donated a library building to his hometown of Woodstock, Vermont as well.[18]

Personal life and death

editIn addition to his railroad activities, Williams also served as a U.S. commissioner to the Sydney International Exhibition in 1879 and the Melbourne International Exhibition in 1880. He also became a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and was decorated as a Knight of the Order of the Polar Star.[19] In 1897 he was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society.[20]

Williams was married to Cornella Bailey Pratt. They had three children: Edward Higginson Williams Jr., William Williams, and Anna (Williams) Dreer.[1]

On 17 June 1861 Cornelia Williams' brother, Officer Nehum M Platt was shot and killed accidentally by Union troops during a demonstration in St. Louis. He was an 11 year veteran of the St. Louis police force and was killed by gunfire. [21][22]

Williams died on December 21, 1899, in Santa Barbara, California. The cause of death was described as “heart troubles”.[18]

References

edit- ^ a b c d Muskett, Joseph James, ed. (1900). "Appleton of New England". Suffolk Manorial Families. 1. Exeter: William Pollard & Co: 334. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- ^ Hebert, J. C. (2001). "The History of Surgery in Vermont". Archives of Surgery. 136 (4): 467–472. doi:10.1001/archsurg.136.4.467. PMID 11296121.

- ^ https://hartfordvthistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Memorandum-for-1872.pdf

- ^ Macmillan, M. (2000). An Odd Kind of Fame: Stories of Phineas Gage. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-13363-6. (hbk, 2000) (pbk, 2002).

- ^ "Cornelia Bailey Pratt Williams".

- ^ "Tau Beta Pi - Our Founder".

- ^ Hebert, J. C. (2001). "The History of Surgery in Vermont". Archives of Surgery. 136 (4): 467–472. doi:10.1001/archsurg.136.4.467. PMID 11296121.

- ^ McIntire, Julia W. (1974). Green mountain heritage: the chronicle of Northfield Vermont. Phoenix Publishing, Canaan NH. pp. 159, 172. ISBN 0-914016-08-3.

- ^ "Central Vermont Railway: List of Railroad Employees".

- ^ Vermont Railroad Commissioner. "Second annual report of the railroad commissioner of the state of Vermont to the general assembly, 1857".

- ^ Annual Report of the Directors of the Galena and Chicago Union Rail Road Co. To the Stockholders for the Fiscal Year Ending December 31. Dunlop, Sewell & Spalding. 1861.

- ^ "Ashcroft's railway directory for 1862". 1862. p. 168.

- ^ Annual Report of the Directors of the Galena and Chicago Union Rail Road Co. To the Stockholders for the Fiscal Year Ending December 31. Dunlop, Sewell & Spalding. 1861. p. 8-9.

- ^ "Ashcroft's railway directory for 1862". 1862. p. 161.

- ^ "Ashcroft's railway directory for 1865". 1862. p. 112-113.

- ^ "Ashcroft's railway directory for ... : Containing an official list of all the officers and directors of the rail-roads in the United States & Canadas, together with their financial condition and amount of rolling stock". 1866.

- ^ "Dr. Edward H. Williams".

- ^ a b DR. EDWARD H. WILLIAMS DEAD. – Part Owner of Baldwin Locomotive Works Succumbs to Heart Trouble. New York Times, December 22, 1899

- ^ Suffolk Manorial Families: Being the County Visitations and Other Pedigrees, Edited, with Extensive Additions. W. Pollard & Company. 1900.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 2024-02-22.

- ^ "Missouri Law Enforcement Memorial".

- ^ "Daily Dispatch".