Diomedes (/ˌdaɪəˈmiːdiːz/[1]) or Diomede (/ˈdaɪəmiːd/;[1] Greek: Διομήδης, translit. Diomēdēs, lit. "god-like cunning" or "advised by Zeus") is a hero in Greek mythology, known for his participation in the Trojan War.

| Diomedes | |

|---|---|

King of Argos | |

| Member of the Achaeans | |

| |

| Other names | Diomede |

| Abode | Argos |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | Tydeus and Deipyle |

| Siblings | Comaetho |

| Consort | Aegialia |

He was born to Tydeus and Deipyle and later became King of Argos, succeeding his maternal grandfather, Adrastus. In Homer's Iliad Diomedes is regarded alongside Ajax the Great and Agamemnon, after Achilles, as one of the best warriors of all the Achaeans in prowess (which is especially made clear in Book 7 of the Iliad when Ajax the Greater, Diomedes, and Agamemnon are the most wished for by the Achaeans to fight Hector out of nine volunteers, who included Odysseus and Ajax the Lesser). Subsequently, Diomedes founded ten or more Italian cities and, after his death, was worshipped as a divine being under various names in both Italy and Greece.

Description edit

In the account of Dares the Phrygian, Diomedes was illustrated as ". . .stocky, brave, dignified, and austere. He was loud at the war-cry, hot-tempered, impatient, and daring."[2]

Early myths edit

Diomedes was, on his father's side, an Aetolian, and on his mother's an Argive. His father, Tydeus, was himself of royal blood, being the son of Oeneus, the king of Calydon. He had been exiled from his homeland for killing his relatives, either his cousins or his paternal uncles. In any case, Tydeus was exiled, and he found refuge at Argos, where the king, Adrastus, offered him hospitality, even giving him his daughter, Deipyle, to be his wife. The two were happily married and had two children together—a daughter, Comaetho, and a son, Diomedes.

Sometime later, Polynices, a banished prince of Thebes, arrived in Argos; he approached Adrastus and pleaded his case to the king, as he requested his aid to restore him to his original homeland. Adrastus promised to do so and set out to gather an expeditionary force with which to march against Thebes. This force was made up of seven individual champions, each assigned to lead an assault on one of the seven gates of the city; Tydeus, Polynices and Adrastus were among them. Together, these champions were known as the Seven against Thebes.

The expedition proved to be a complete disaster, however, as all seven of the Argive champions were killed in the ensuing battle, except for Adrastus, who escaped thanks to his horse Arion, who was the fastest of all of his brethren. Diomedes' father, Tydeus, was among those who had been slain.

Tydeus was Athena's favorite warrior at the time, and when he was dying she wanted to offer him a magic elixir (which she had obtained from her father) that would make him immortal. However, she withdrew the intended privilege in apparent disgust when Tydeus gobbled down the brains of the hated enemy who had wounded him.[3]

Diomedes was four years old when his father was killed. At the funeral of their fathers, the sons of the seven fallen champions (Aegialeus, Alcmaeon, Amphilocus, Diomedes, Euryalus, Promachus, Sthenelus, and Thersander) met and vowed to vanquish Thebes in order to avenge their fathers. These seven sons were known as the Epigoni ("offspring").

Ten years later, the Epigoni set out to launch another expedition against Thebes, appointing Alcmaeon as their commander-in-chief. They strengthened their initial forces with contingents from Messenia, Arcadia, Corinth, and Megara. This army, however, was still small compared to that of Thebes.

The war of the Epigoni is remembered as the most important expedition in Greek mythology prior to the Trojan War. It was a favorite topic for epics, but, all of these epics are now lost. The main battle took place at Glisas where Prince Aegialeus (son of Adrastus and heir to the throne) was slain by King Laodamas, who was in turn killed by Alcmaeon. With their king dead, the Thebans, believing this to be the end for them, sought counsel from the seer Tiresias, who urged them to flee the city. They did so, and, faced with no opposition, the Epigoni entered the city, plundering its treasures and tearing down its great walls. Having achieved their objective, the Epigoni returned home, but not before they installed Thersander, son of the fallen prince Polynices (the instigator of the first Theban expedition), as the city's new ruler.[4]

As Diomedes and the Argive forces travelled home, an elderly King Adrastus died of grief upon learning that his son Aegialeus had perished in the battle; as such, Diomedes was left as the last of Adrastus' male descendants. That being so, upon returning home to Argos, Diomedes ascended to the throne. In order to secure his grasp on the throne, Diomedes married Aegialeus' daughter, Princess Aegialia.[5]

Diomedes ruled Argos for more than five years and brought much wealth and stability to the city during his time. He was a skilled politician and was greatly respected by other rulers. He still kept an eye on Calydonian politics (his father's homeland), and when the sons of Agrius (led by Thersites) put Oeneus (Diomedes' grandfather) in jail and their own father on the throne, Diomedes decided to restore Oeneus to the throne.

Diomedes attacked and seized the kingdom, slaying all the traitors except Thersites, Onchestus (who escaped to Peloponnesus) and Agrius (who killed himself) restoring his grandfather to the throne. Later, Oeneus passed the kingdom to his son-in-law, Andraemon, and headed to Argos to meet Diomedes. He was assassinated on the way (in Arcadia) by Thersites and Onchestus. Unable to find the murderers, Diomedes founded a mythical city called "Oenoe" at the place where his grandfather was buried to honour his death. Later, Thersites fought against the Trojans in the Trojan War and noble Diomedes did not mistreat him (however, Thersites was hated by all the other Achaeans). In fact, when Thersites was brutally slain by Achilles (after having mocked him when the latter cried over Penthesilia's dead body), Diomedes was the only person who wanted to punish Achilles.[6]

According to Hyginus and Pseudo-Apollodorus, Diomedes became one of the suitors of Helen and, as such, he was bound by the oath of Tyndareus, which established that all the suitors would defend and protect the man who was chosen as Helen's husband against any wrong done against him in regard to his marriage. Accordingly, when the Trojan prince Paris stole Menelaus' wife, all those who had sworn the oath were summoned by Agamemnon (Menelaus' brother), so that they would join the coalition that was to sail from Aulis to Troy in order to retrieve Helen and the Spartan property that was stolen.[7] However, Hesiod does not include Diomedes in his list of suitors. It's possible that labelling Diomedes a suitor of Helen was a later addition, extrapolated from his name being listed in the Catalogue of Ships. If, in fact, Helen ruled Sparta with her husband Menelaus for ten years before her abduction, Diomedes would have still been a child at the time of their marriage and thus a very unlikely suitor.[8]

Trojan War edit

Diomedes is known primarily for his participation in the Trojan War. According to Homer, Diomedes entered the war with a fleet of 80 ships, third only to the contributions of Agamemnon (100 ships) and Nestor (90). Both Sthenelus and Euryalus (former Epigoni) fought under his command with their armies. Sthenelus was the driver of Diomedes' chariot and probably his closest friend. All the troops from Argos, Tiryns, Troezen and some other cities were headed by Diomedes.

Although he was the youngest of the Achaean kings, Diomedes is considered the most experienced leader by many scholars (he had fought more battles than others, including the war of the Epigoni, the most important war expedition before the Trojan War – even old Nestor had not participated in such military work).[citation needed] Second only to Achilles, Diomedes is considered to be the mightiest and the most skilled warrior among the Achaeans.[citation needed] He was overwhelming Telamonian Ajax in an armed sparring contest when the watching Achaeans bade the men to stop and take equal prizes because they feared for Ajax's life. Ajax gave Diomedes the prize (long sword) because Diomedes drew the first blood. He vanquished (and could have killed) Aeneas (the second best Trojan warrior) once. He and Odysseus were the only Achaean heroes who participated in covert military operations that demanded discipline, bravery, courage, cunning, and resourcefulness.

Diomedes received the most direct divine help and protection. He was the favorite warrior of Athena (who even drove his chariot once). He was also the only hero except Heracles, son of Zeus, that attacked Olympian gods. He even wounded Ares, whom he struck with his spear. Once, he was even granted divine vision in order to identify immortals. Only Diomedes and Menelaus were offered immortality and became gods in post-Homeric mythology.

The god Hephaestus made Diomedes' cuirass for him. He was the only Achaean warrior apart from Achilles who carried such an arsenal of gear made by Hera's son. He also had a round shield with the mark of a boar. In combat, he also carried a spear, which wasn't enchanted as well as his father's sword. His golden armor bore a crest of a boar on the breast. It was created by a mortal smith but was blessed by Athena, who gave it to Tydeus. When he died, it passed to Diomedes. A skilled smith created the sword for Tydeus, which bore designs of a lion and a big boar.

Diomedes in Aulis edit

In Aulis, where the Achaean leaders gathered, Diomedes met his brother in arms Odysseus, with whom he shared several adventures. Both of them were favorite heroes of Athena and each shared characteristics of their patron goddess – Odysseus her wisdom and cunning, and Diomedes her courage and skill in battle; though neither was wholly bereft of either aspect. They began to combine their efforts and actions already when being in Aulis.

When the sacrifice of Iphigenia (Agamemnon's daughter) became a necessity for the Achaeans to sail away from Aulis, King Agamemnon had to choose between sacrificing his daughter and resigning from his post of high commander among Achaeans. When he decided to sacrifice his daughter to Artemis, Odysseus carried out this order of Agamemnon by luring Iphigenia from Mycenae to Aulis, where murder, disguised as wedding, awaited her.[9] According to Hyginus, Diomedes went with Odysseus to fetch Iphigenia, making this the two companions' first mission together.[10] However, Pseudo-Apollodorus has Agamemnon send Odysseus and Talthybius instead.[11] According to Euripides, neither of the two went to fetch Iphigenia, though he calls the plan Odysseus' idea in Iphigenia at Taurus.[12]

Palamedes edit

Once in Troy, Odysseus murdered Palamedes (the commander who outwitted Odysseus in Ithaca, proving him to be feigning insanity and thus forcing him to stand by his oath and join the alliance), drowning him while he was fishing. According to other stories, when Palamedes advised the Achaeans to return home, Odysseus accused him of being a traitor and forged false evidence and found a fake witness to testify against him,[13] whereupon Palamedes was stoned to death.

Some say that both Diomedes and Odysseus drowned Palamedes.[14] Another version says that he conspired with Odysseus against Palamedes,[15] and under the pretence of having discovered a hidden treasure, they let him down into a well and there stoned him to death.[16] Others say that, though Diomedes guessed or knew about the plot, he did not try to defend Palamedes, because Odysseus was essential for the fall of Troy.

Diomedes in the Iliad edit

Diomedes is one of the main characters in the Iliad. This epic narrates a series of events that took place during the final year of the great war. Diomedes is the key fighter in the first third of the epic. According to some interpretations, Diomedes is represented in the epic as the most valiant soldier of the war, who avoids committing hubris. He is regarded as the perfect embodiment of traditional heroic values. While striving to become the best warrior and attain honor and glory, he does not succumb to the madness which 'menos' might entail.

He was the only human except for Heracles to be granted strength (with permission) to directly fight with immortals themselves and injures two Olympian immortals (both Ares and Aphrodite) in a single day. However, he still displays self-restraint and humility to retreat before Ares and give way to Apollo thus remaining within mortal limits. This is in contrast to Patroclus (who does not give way when opposed by Apollo) and Achilles (who resorts to fight the river Scamander on his own).

His character also helps to establish one of the main themes of the epic: how human choices and efforts become insignificant when fate and immortals are in control. Diomedes follows Homeric tradition closely and having absolute faith on the superiority of fate, he predicts the conclusion of Achilles' efforts to go against fate.

Apart from his outstanding fighting abilities and courage, Diomedes is on several crucial occasions shown to possess great wisdom, which is acknowledged and respected by his much older comrades, including Agamemnon and Nestor. Diomedes, Nestor and Odysseus were some of the greatest Achaean strategists. Throughout the Iliad, Diomedes and Nestor are frequently seen speaking first in war-counsel.

Instances of Diomedes' maturity and intelligence as described in parts of the epic:

- In Book IV Agamemnon taunts Diomedes by calling him a far inferior fighter compared to his father. His enraged comrade Sthenelus urges Diomedes to stand up to Agamemnon by responding that he has bested his father and avenged his death by conquering Thebes. Diomedes responded that it was part of Agamemnon's tasks as a leader to urge forward the Achaean soldiers, and that men of valour should have no problem withstanding such insults. However, when Agamemnon earlier uses the same kind of taunting on Odysseus, he responds with anger.

- Although Diomedes dismissed Agamemnon's taunting with respect, he did not hesitate to point out Agamemnon's inadequacy as a leader in certain crucial situations. In Book IX, Agamemnon proposes going back to Hellas because Zeus has turned against them. Diomedes then reminds him of the previous insult and tells him that his behavior is not proper for a leader. Achaean council – Book IX

- Diomedes points out that because Troy is destined to fall, they should continue fighting regardless of Zeus' interventions. Fate and gods were with Achaeans at the start and therefore Zeus' interventions could only be temporary. Even if all other Achaeans lost their faith and went home, he and Sthenelus would still remain and continue to fight till Troy was sacked.

- "The sons of the Achaeans shouted applause at the words of Diomedes, and presently Nestor rose to speak. 'Son of Tydeus,' said he, 'in war your prowess is beyond question, and in council you excel all who are of your own years; no one of the Achaeans can make light of what you say nor gainsay it, but you have not yet come to the end of the whole matter. You are still young—you might be the youngest of my own children—still you have spoken wisely and have counselled the chief of the Achaeans not without discretion;'" Achaean council – Book IX

- When Agamemnon tried to appease Achilles's wrath so that he would fight again, by offering him many gifts, Nestor appointed three envoys to meet Achilles (Book IX). They had to return empty handed; Achilles had told them that he will leave Troy and never return. The Achaeans were devastated at this. Diomedes points out the folly of offering these gifts which ultimately served only to encourage Achilles' pride to the level that he now wishes to defy fate. Diomedes then makes a prediction (based on Homeric tradition) that eventually becomes true. He says that even if Achilles somehow manages to leave Troy, he will never be able to stay away from battle because human efforts and choice cannot defy fate; "let him go or stay—the gods will make sure that he will fight." In Book XV, Zeus says to Hera that he had already made a plan to make sure that Achilles will eventually enter the battle.

- Diomedes also encourages Agamemnon to take the lead of next day's battle. "But when fair rosy-fingered morn appears, forthwith bring out your host and your horsemen in front of the ships, urging them on, and yourself fighting among the foremost." (Book IX) Agamemnon accepts this counsel and the next day's battle starts with his "aristeia" where he becomes the hero of the day.

Diomedes' aristeia ("excellence"—the great deeds of a hero) begins in Book V and continues in Book VI. This is the longest aristeia in the epic. Some scholars claim that this part of the epic was originally a separate, independent poem (describing the feats of Diomedes) that Homer adapted and included in the Iliad.[17] Diomedes' aristeia represents many of his heroic virtues such as outstanding fighting skills, bravery, divine protection/advice, carefully planned tactics of war, leadership, humility and self-restraint.

Book V edit

Book V begins with Athena, the war-like goddess of wisdom putting valour into the heart of her champion warrior. She also makes a stream of fire flare from his shield and helmet. Diomedes then slays a number of Trojan warriors including Phegeus (whose brother was spirited away by Hera's son, Hephaestus before being slain by Diomedes) until Pandarus wounds him with an arrow. Diomedes then prays to Athena for the slaughter of Pandarus. She responds by offering him a special vision to distinguish gods from men and asks him to wound Aphrodite if she ever comes to battle. She also warns him not to engage any other god.

He continues to make havoc among the Trojans by killing Astynous, Hypeiron, Abas, Polyidus, Xanthus, Thoon, Echemmon and Chromius (two sons of Priam). Finally, Aeneas (son of Aphrodite) asks Pandarus to mount his chariot so that they may fight Diomedes together. Sthenelus warns his friend of their approach.

Diomedes faces this situation by displaying both his might and wisdom. Although he can face both of these warriors together, he knows that Aphrodite may try to save her son. He also knows the history of Aeneas' two horses (they descend from Zeus's immortal horses). Since he has to carry out Athena's order, he orders Sthenelus to steal the horses while he faces Aphrodite's son.

Pandarus throws his spear first and brags that he has killed the son of Tydeus. The latter responds by saying "at least, one of you will be slain" and throws his spear. Pandarus is killed and Aeneas is left to fight Diomedes (now unarmed). Not bothering with weapons, Diomedes picks up a huge stone and crushes his enemy's hip with it. Aeneas faints and is rescued by his mother before Diomedes can kill him. Mindful of Athena's orders, Diomedes runs after Aphrodite and wounds her arm. Dropping her son, the goddess flees towards Olympus. Apollo now comes to the rescue of the Trojan hero. Disregarding Athena's advice, Diomedes attacks Apollo three times before Apollo warns him not to match himself against immortals. Respecting Apollo, Diomedes then withdraws himself from that combat. Although he has failed in killing Aeneas, Sthenelus, following his orders, has already stolen the two valuable horses of Aeneas. Diomedes then became the owner of the second best pair of horses (after Achilles' immortal ones) among Achaeans.

Aphrodite complained to her mother about Diomedes' handiwork. The latter reminded her of mighty Heracles (now, an Olympian himself) who held the record of wounding not one but two Olympians as a human.

The transgression of Diomedes by attacking Apollo had its consequences. Urged by Apollo, Ares came to the battlefield to help Trojans. Identifying the god of war, Diomedes protected the Achaeans by ordering them to withdraw towards their ships. Hera saw the havoc created by her son and together with Athena, she came to the Achaeans' aid. When Athena saw Diomedes resting near his horses, she mocked him, reminding him of Tydeus who frequently disobeyed her advice. Diomedes replied, "Goddess, I know you truly and will not hide anything from you. I am following your instructions and retreating for I know that Ares is fighting among the Trojans". Athena answered "Diomedes most dear to my heart, do not fear this immortal or any other god for I will protect you." Throwing Sthenelus out of the chariot and mounting it herself, the goddess (who invented the chariot and taught humans to drive it) drove straight at Ares. She also put on the helmet of Hades, making her invisible to even gods. Ares saw only Diomedes in the chariot and threw his spear which was caught by Athena. Diomedes then threw his spear (which was guided by Athena) at Ares, wounding his stomach. The god screamed in a voice of ten thousand men and fled away. This was how Diomedes became the only human to wound two Olympians in a single day.

Book VI edit

Diomedes continued his feats by killing Axylus and Calesius. Hector's brother Helenus described Diomedes' fighting skills in this manner: "He fights with fury and fills men's souls with panic. I hold him mightiest of them all; we did not fear even their great champion Achilles, son of an immortal though he be, as we do this man: his rage is beyond all bounds, and there is none can vie with him in prowess."

Helenus then sent Hector to the city of Troy to tell their mother about what was happening. According to the instructions of Helenus, Priam's wife gathered matrons at the temple of Athena in the acropolis and offered the goddess the largest, fairest robe of Troy. She also promised the sacrifice of twelve heifers if Athena could take pity on them and break the spear of Diomedes. Athena, of course, did not grant it.

Meanwhile, one brave Trojan named Glaucus challenged the son of Tydeus to a single combat. Impressed by his bravery and noble appearance, Diomedes inquired if he were an immortal in disguise. Although Athena has previously told him not to fear any immortal, Diomedes displayed his humility by saying, "I will not fight any more immortals."

Glaucus told the story of how he was descended from Bellerophon who killed the Chimaera and the Amazons. Diomedes realized that his grandfather Oeneus hosted Bellerophon, and so Diomedes and Glaucus must also be friends. They resolved to not fight each other and Diomedes proposed exchanging their armours. Cunning Diomedes only gave away a bronze armour for the golden one he received. The phrase 'Diomedian swap' originated from this incident.

Book VII edit

Diomedes was among the nine Achaean warriors who came forward to fight Hector in a single combat. When they cast lots to choose one among those warriors, the Achaeans prayed "Father Zeus, grant that the lot fall on Ajax, or on the son of Tydeus, or upon Agamemnon." Ajax was chosen to fight Hector.

Idaeus of the Trojans came for a peace negotiation, and he offered to give back all the treasures Paris stole plus more—everything except Helen. In the Achaean council, Diomedes was the first one to speak: "Let there be no taking, neither treasure, nor yet Helen, for even a child may see that the doom of the Trojans is at hand." These words were applauded by all and Agamemnon said, "This is the answer of the Achaeans."

Book VIII edit

Zeus ordered all other deities to not interfere with the battle. He made the Trojans stronger so they could drive away the Achaeans from battle. Then he thundered aloud from Ida and sent the glare of his lightning upon the Achaeans. Seeing this, all the great Achaean warriors—including the two Ajaxes, Agamemnon, Idomeneus and Odysseus—took flight. Nestor could not escape because one of his horses was wounded by Paris' arrow. He might have perished if not for Diomedes.

This incident is the best example for Diomedes' remarkable bravery. Seeing that Nestor's life was in danger, the son of Tydeus shouted for Odysseus' help. The latter ignored his cry and ran away. Left alone in the battleground, Diomedes took his stand before Nestor and ordered him to take Sthenelus' place. Having Nestor as the driver, Diomedes bravely rushed towards Hector. Struck by his spear, Hector's driver Eniopeus was slain. Taking a new driver, Archeptolemus, Hector advanced forward again. Zeus saw that both Hector and Archeptolemus were about to be slain by Diomedes and decided to intervene. He took his mighty Thunderbolt and shot its lightning in front of Diomedes' chariot. Nestor advised Diomedes to turn back since no person should try to transgress Zeus' will. Diomedes answered, "Hector will talk among the Trojans and say, 'The son of Tydeus fled before me to the ships.' This is the vaunt he will make, and may the earth then swallow me." Nestor responded, "Son of Tydeus, though Hector say that you are a coward the Trojans and Dardanians will not believe him, nor yet the wives of the mighty warriors whom you have laid low." Saying these words, Nestor turned the horses back. Hector, seeing that they had turned back from battle, called Diomedes a "woman and a coward" and promised to slay him personally. Diomedes thought three times of turning back and fighting Hector, but Zeus thundered from heaven each time.

When all the Achaean seemed discouraged, Zeus sent an eagle as a good omen. Diomedes was the first warrior to read this omen, and he immediately attacked the Trojans and killed Agelaus.

At the end of the day's battle, Hector made one more boast, "Let the women each of them light a great fire in her house, and let watch be safely kept lest the town be entered by surprise while the host is outside... I shall then know whether brave Diomed will drive me back from the ships to the wall, or whether I shall myself slay him and carry off his bloodstained spoils. Tomorrow let him show his mettle, abide my spear if he dare. I ween that at break of day, he shall be among the first to fall and many another of his comrades round him. Would that I were as sure of being immortal and never growing old, and of being worshipped like Athena and Apollo, as I am that this day will bring evil to the Argives."

These words subsequently turned out to be wrong. In spite of careful watch, Diomedes managed to launch an attack upon the sleeping Trojans. Hector was vanquished by Diomedes yet again and it was Diomedes that ended up being worshipped as an immortal.

Book IX edit

Agamemnon started shedding tears and proposed to abandon the war for good because Zeus was supporting the Trojans. Diomedes pointed out that this behavior was inappropriate for a leader like Agamemnon. He also declared that he will never leave the city unvanquished for the gods were originally with them. This speech signifies the nature of Homeric tradition where fate and divine interventions have superiority over human choices. Diomedes believed that Troy was fated to fall and had absolute and unconditional faith in victory.

However, this was one of the two instances where Diomedes' opinion was criticized by Nestor. He praised Diomedes' intelligence and declared that no person of such young age could equal Diomedes in counsel. He then criticized Diomedes for not making any positive proposal to replace Agamemnon's opinion – a failure which Nestor ascribed to his youth. Nestor believed in the importance of human choices and proposed to change Achilles' mind by offering many gifts. This proposal was approved by both Agamemnon and Odysseus.

The embassy failed because Achilles himself had more faith in his own choices than fate or divine interventions. He threatened to leave Troy, never to return believing that this choice will enable him to live a long life. When the envoys returned, Diomedes criticized Nestor's decision and Achilles' pride saying that Achilles' personal choice of leaving Troy is of no importance (therefore, trying to change it with gifts is useless). Diomedes said, "Let Achilles stay or leave if he wishes to, but he will fight when the time comes. Let's leave it to the gods to set his mind on that." (In Book 15, Zeus tells Hera that he has already planned the method of bringing Achilles back to battle, confirming that Diomedes was right all along)

Book X edit

Agamemnon and Menelaus rounded up their principal commanders to get ready for battle the next day. They woke up Odysseus, Nestor, Ajax, Diomedes and Idomeneus. While the others were sleeping inside their tents, king Diomedes was seen outside his tent clad in his armour sleeping upon an ox skin, already well-prepared for any problem he may encounter at night. During the Achaean council held, Agamemnon asked for a volunteer to spy on the Trojans. Again, it was Diomedes who stepped forward.

The son of Tydeus explained "If another will go with me, I could do this in greater confidence and comfort. When two men are together, one of them may see some opportunity which the other has not caught sight of; if a man is alone he is less full of resource, and his wit is weaker." These words inspired many other heroes to step forward. Agamemnon put Diomedes in charge of the mission and asked him to choose a companion himself. The hero instantly selected Odysseus for he was loved by Athena and was quick witted. Although Odysseus had deserted Diomedes in the battlefield that very day, instead of criticizing him, the latter praised his bravery in front of others. Odysseus' words hinted that he actually did not wish to be selected.

Meanwhile, in a similar council held by Hector, not a single prince or king would volunteer to spy on Achaeans. Finally Hector managed to send Dolon, a good runner, after making a false oath (promising him Achilles' horses after the victory).

On their way to the Trojan camp, Diomedes and Odysseus discovered Dolon approaching the Achaean camp. The two kings lay among the corpses till Dolon passed them and ran after him. Dolon proved to be the better runner but Athena infused fresh strength into the son of Tydeus for she feared some other Achaean might earn the glory of being first to hit Dolon. Diomedes threw his spear over Dolon's shoulders and ordered him to stop.

Dolon gave them several valuable pieces of information. According to Dolon, Hector and the other councilors were holding conference by the monument of great Ilus, away from the general tumult. In addition, he told about a major weakness in Trojan army. Only the Trojans had watchfires; they, therefore, were awake and kept each other to their duty as sentinels; but the allies who have come from other places were asleep and left it to the Trojans to keep guard. It is never explained in the epic why Dolon, specially mentioned as a man of lesser intelligence, came to notice this flaw while Hector (in spite of all his boasting) completely missed/ignored it.

On further questioning, Diomedes and Odysseus learnt that among the various allies, Thracians were the most vulnerable for they had come last and were sleeping apart from the others at the far end of the camp. Rhesus was their king and Dolon described Rhesus' horses in this manner; "His horses are the finest and strongest that I have ever seen, they are whiter than snow and fleeter than any wind that blows".

Having truthfully revealed valuable things, Dolon expected to be taken as a prisoner to the ships, or to be tied up, while the other two found out whether he had told them the truth or not. But Diomedes told him: "You have given us excellent news, but do not imagine you are going to get away, now that you have fallen into our hands. If we set you free tonight, there is nothing to prevent your coming down once more to the Achaean ships, either to play the spy or to meet us in open fight. But if I lay my hands on you and take your life, you will never be a nuisance to the Argives again." Having said this, Diomedes cut off the prisoner's head with his sword, without giving him time to plead for his life.

Although the original purpose of this night mission was spying on the Trojans, the information given by Dolon persuaded the two friends to plan an attack upon the Thracians. They took the spoils and set them upon a tamarisk tree in honour of Athena. Then they went where Dolon had indicated, and having found the Thracian king, Diomedes let him and twelve of his soldiers pass from one kind of sleep to another; for they were all killed in their beds, while asleep. Meanwhile, Odysseus gathered the team of Rhesus' horses. Diomedes was wondering when to stop. He was planning to kill some more Thracians and stealing the chariot of the king with his armour when Athena advised him to back off for some other god may warn the Trojans.

This first night mission demonstrates another side of these two kings where they employed stealth and treachery along with might and bravery. In Book XIII, Idomeneus praises Meriones and claims the best warriors do in fact excel in both types of warfare, 'lokhos' (ambush) and 'polemos' (open battle). Idomeneus' words portray ambush, "the place where the merit of men most shines through, where the coward and the resolute man are revealed", as type of warfare only for the bravest.[18]

The first night mission also fulfills one of the prophecies required for the fall of Troy: that Troy will not fall while the horses of Rhesus feed upon its plains. According to another version of the story, it had been foretold by an oracle that if the stallions of Rhesus were ever to drink from the river Scamander, which cuts across the Trojan plain, then the city of Troy would never fall. The Achaeans never allowed the horses to drink from that river for all of them were stolen by Diomedes and Odysseus shortly after their arrival. In a different story (attributed to Pindar), Rhesus fights so well against the Achaeans that Hera sends Odysseus and Diomedes to kill him secretly at night. Another version (Virgil and Servius) says that Rhesus was given an oracle that claims he will be invincible after he and his horses drink from the Scamander. In all these versions, killing Rhesus by Diomedes was instrumental for the victory. The horses of Rhesus were given to king Diomedes.

According to some scholars, the rest of Thracians, deprived of their king, left Troy to return to their kingdom. This was another bonus of the night mission.

Book XI edit

In the forenoon, the fight was equal, but Agamemnon turned the fortune of the day towards the Achaeans until he got wounded and left the field. Hector then seized the battlefield and slew many Achaeans. Beholding this, Diomedes and Odysseus continued to fight with a lot of valor, giving hope to the Achaeans. The king of Argos slew Thymbraeus, two sons of Merops, and Agastrophus.

Hector soon marked the havoc Diomedes and Odysseus were making, and approached them. Diomedes immediately threw his spear at Hector, aiming for his head. This throw was dead accurate but the helmet given by Apollo saved Hector's life. Yet, the spear was sent with such great force that Hector swooned away. Meanwhile, Diomedes ran towards Hector to get his spear. Hector recovered and mingled with the crowd, by which means he saved his life from Diomedes for the second time. Frustrated, Diomedes shouted after Hector calling him a dog. The son of Tydeus, frequently referred to as the lord of war cry, was not seen speaking disrespectful words to his enemies before.

Shortly after that Paris jumped up in joy for he managed to achieve a great feat by fixing Diomedes' foot to the ground with an arrow. Dismayed at this, Diomedes said "Seducer, a worthless coward like you can inflict but a light wound; when I wound a man though I but graze his skin it is another matter, for my weapon will lay him low. His wife will tear her cheeks for grief and his children will be fatherless: there will he rot, reddening the earth with his blood, and vultures, not women, will gather round him." Under Odysseus' cover, Diomedes withdrew the arrow but unable to fight with a limp, he retired from battle.

Book XIV edit

The wounded kings (Diomedes, Agamemnon and Odysseus) held council with Nestor regarding the possibility of Trojan army reaching their ships. Agamemnon proposed drawing the ships on the beach into the water but Odysseus rebuked him and pointed out the folly of such council. Agamemnon said, "Someone, it may be, old or young, can offer us better counsel which I shall rejoice to hear." Wise Diomedes said, "Such a one is at hand; he is not far to seek, if you will listen to me and not resent my speaking though I am younger than any of you ... I say, then, let us go to the fight as we needs must, wounded though we be. When there, we may keep out of the battle and beyond the range of the spears lest we get fresh wounds in addition to what we have already, but we can spur on others, who have been indulging their spleen and holding aloof from battle hitherto." This council was approved by all.

Book XXIII edit

In the funeral games of Patroclus, Diomedes (though wounded) won all the games he played. First, he participated in the chariot race where he had to take the last place in the starting-line (chosen by casting lots). Diomedes owned the fastest horses after Achilles (who did not participate). A warrior named Eumelus took the lead and Diomedes could have overtaken him easily but Apollo (who had a grudge against him) made him drop the whip. Beholding this trick played by the sun god, Athena reacted with great anger. She not only gave the whip back to the son of Tydeus but also put fresh strength to his horses and went after Eumelus to break his yoke. Poor Eumelus was thrown down and his elbows, mouth, and nostrils were all torn. Antilochus told his horses that there is no point trying to overtake Diomedes for Athena wishes his victory. Diomedes won the first prize – "a woman skilled in all useful arts, and a three-legged cauldron". The chariot race is considered as the most prestigious competition in the funeral games and the most formal occasion for validating the status of the elite.[19] In this way Diomedes asserts his status as the foremost Achaean hero after Achilles.

Next, he fought with great Ajax in an armed sparring contest where the winner was to draw blood first. Ajax attacked Diomedes where his armour covered his body and achieved no success. Ajax owned the biggest armour and the tallest shield which covered most of his body leaving only two places vulnerable; his neck and armpits. So, Diomedes maneuvered his spear above Ajax's shield and attacked his neck, drawing blood. The Achaean leaders were scared that another such blow would kill Ajax and they stopped the fight. Diomedes received the prize for the victor. This is the final appearance of Diomedes in the epic.

Role as Athena's favored warrior edit

It is generally accepted that Athena is closest to Diomedes in the epic. For example, although both Odysseus and Diomedes were favorites of the goddess Athena, Odysseus prayed for help even before the start of the above footrace, whereas Diomedes received Athena's help without having to ask. Moreover, the goddess spoke to the hero without any disguise in Book V where he could see her in the true divine form (a special vision was granted to him). Such an incident doesn't happen even in the other Homeric epic, The Odyssey, where Athena always appears to Odysseus in disguise.

Posthomerica edit

Penthesileia led a small army of Amazons to Troy for the last year of the Trojan War. Two of her warriors, named Alcibie and Derimacheia, were slain by Diomedes. Penthesileia killed many Achaeans in battle. She was, however, no match for Achilles, who killed her. When Achilles stripped Penthesileia of her armour, he saw that the woman was young and very beautiful, and seemingly falls madly in love with her. Achilles then regrets killing her. Thersites mocked Achilles for his behaviour, because the hero was mourning his enemy. Enraged, Achilles killed Thersites with a single blow to his face.

Thersites was so quarrelsome and abusive in character that only his cousin, Diomedes, mourned for him. Diomedes wanted to avenge Thersites, but the other leaders persuaded the two mightiest Achaean warriors against fighting each other. Hearkening to prayers of comrades, the two heroes reconciled at last. According to Quintus Smyrnaeus, the Achaean leaders agreed to the boon of returning her body to the Trojans for her funeral pyre. According to some other sources, Diomedes angrily tossed Penthesileia's body into the river, so neither side could give her decent burial.[6]

Nestor's son was killed by Memnon, and Achilles held funeral games for Antilochus. Diomedes won the sprint.[20] After Achilles' death, the Achaeans piled him a mound and held magnificent games in his honor. According to Apollodorus, Diomedes won the footrace. Quintus of Smyrna says that the wrestling match between him and Ajax the Great came to a draw. After the death of Achilles, it was prophesied that Troy could not be taken if Neoptolemus (Achilles's son) would not come and fight. According to Quintus Smyrnaeus, Odysseus and Diomedes came to Scyros to bring him to the war at Troy. According to the Epic Cycle, Odysseus and Phoenix did this.

The Achaean seer Calchas prophesied that Philoctetes (whom the Achaeans had abandoned on the island of Lemnos due to the vile odour from snakebite) and the bow of Heracles are needed to take Troy. Philoctetes hated Odysseus, Agamemnon and Menelaus, because they were responsible for leaving him behind. Diomedes and Odysseus were charged with achieving this prophecy also. Knowing that Philoctetes would never agree to come with them, they sailed to the island and stole the bow of Heracles by a trick. According to the Little Iliad, Odysseus wanted to sail home with the bow but Diomedes refused to leave Philoctetes behind. Heracles (now a god) or Athena then persuaded Philoctetes to join the Achaeans again (with the promise that he would be healed) and he agreed to go with Diomedes. The bow of Heracles and the poisoned arrows were used by Philoctetes to slay Paris; this was a requirement to the fall of Troy.

According to some, Diomedes and Odysseus were sent into the city of Troy to negotiate for peace after the death of Paris.[21]

The Palladium edit

After Paris' death, Helenus left the city but was captured by Odysseus. The Achaeans somehow managed to persuade the seer/warrior to reveal the weakness of Troy. The Achaeans learnt from Helenus, that Troy would not fall, while the Palladium, image or statue of Athena, remained within Troy's walls. The difficult task of stealing this sacred statue again fell upon the shoulders of Odysseus and Diomedes.[22]

Odysseus, some say, went by night to Troy, and leaving Diomedes waiting, disguised himself and entered the city as a beggar. There he was recognized by Helen, who told him where the Palladium was. Diomedes then climbed the wall of Troy and entered the city. Together, the two friends killed several guards and one or more priests of Athena's temple and stole the Palladium "with their bloodstained hands".[23] Diomedes is generally regarded as the person who physically removed the Palladium and carried it away to the ships. There are several statues and many ancient drawings of him with the Palladium.

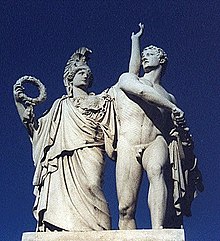

According to the Little Iliad, on the way to the ships, Odysseus plotted to kill Diomedes and claim the Palladium (or perhaps the credit for gaining it) for himself. He raised his sword to stab Diomedes in the back. Diomedes was alerted to the danger by glimpsing the gleam of the sword in the moonlight. He turned round, seized the sword of Odysseus, tied his hands, and drove him along in front, beating his back with the flat of his sword.[24] Because Odysseus was essential for the destruction of Troy, Diomedes refrained from punishing him. From this action was said to have arisen the Greek proverbial expression "Diomedes' necessity", applied to those who act contrary to their inclination for the greater good.[25] The expression 'Diomedeian Compulsion' also originated from this.[26] (The incident was commemorated in 1842 by the French sculptor Pierre-Jules Cavelier in a muscle-bound plaster statue).

Diomedes took the Palladium with him when he left Troy. According to some, he brought it to Argos where it remained until Ergiaeus, one of his descendants, took it away with the assistance of the Laconian Leagrus, who conveyed it to Sparta.[27] Others say that he brought it to Italy. Some say that Diomedes was robbed of the palladium by Demophon in Attica, where he landed one night on his return from Troy, without knowing where he was.[28] According to another tradition, the Palladium failed to bring Diomedes any luck due to the unrighteous way he obtained it. He was informed by an oracle, that he should be exposed to unceasing sufferings unless he restored the sacred image to the Trojans. Therefore, he gave it back to his enemy, Aeneas.[29]

Stealing the Palladium after killing the priests was viewed as the greatest transgression committed by Diomedes and Odysseus by Trojans. Odysseus used this sentiment to his advantage when he invented the Trojan Horse stratagem.

The Wooden Horse edit

This stratagem invented by Odysseus made it possible to take the city. Diomedes was one of the warriors inside. He slew many Trojan warriors inside the city.

According to Quintus Smyrnaeus, while slaughtering countless Trojans, Diomedes met an elderly man named Ilioneus who begged for mercy. Despite his fury of war, Diomedes held back his sword so that the old man might speak. Ilioneus begged "Oh compassionate my suppliant hands! To slay the young and valiant is a glorious thing; but if you smite an old man, small renown waits on your prowess. Therefore turn from me your hands against young men, if you hope ever to come to grey hairs such as mine." Firmly resolved in his purpose, Diomedes answered. "Old man, I look to attain to honored age; but while my Strength yet exists, not a single foe will escape me with life. The brave man makes an end of every foe." Having said this, Diomedes slew Ilioneus.

Some of the other Trojan warriors slain by Diomedes during that night were Coroebus who came to Troy to win the hand of Cassandra,[30] Eurydamas and Eurycoon. Cypria says that Polyxena died after being wounded by Odysseus and Diomedes in the capture of the city.[31]

After the Trojan War edit

After the fall of Troy edit

During the sacking and looting of the great city, the seeress Cassandra, daughter of Priam and Hecuba, clung to the statue of Athena, but the Lesser Ajax raped her. Odysseus, unsuccessfully, tried to persuade the Achaean leaders to put Ajax to death, by stoning the Locrian leader (to divert the goddess's anger). The other Achaean leaders disagreed because Ajax himself clung to the same statue of Athena in order to save himself. The failure of Achaean leaders to punish Ajax the Lesser for the sacrilege of Athena's altar resulted in earning her wrath.

Athena caused a quarrel between Agamemnon and Menelaus about the voyage from Troy. Agamemnon then stayed on to appease the anger of Athena. Diomedes and Nestor held a discussion about the situation and decided to leave immediately. They took their vast armies and left Troy. They managed to reach home safely but Athena called upon Poseidon to bring a violent storm upon most of the other Achaean ships. Diomedes is one of the few Achaean commanders to return home safely, arriving in Argos only four days after his departure from Troy. Since the other Achaeans suffered during their respective 'nostoi' (Returns) because they committed an atrocity of some kind, Diomedes' safe nostos implies that he had the favour of the gods during his journey.[32]

The Palamedes affair haunted several Achaean leaders including Diomedes. Palamedes's brother Oeax went to Argos and reported to Aegialia, falsely or not, that her husband was bringing a woman he preferred to his wife. Others say that Aegialia herself had taken a lover, Cometes (son of Sthenelus), being persuaded to do so by Palamedes's father Nauplius. Still others say that despite Diomedes's noble treatment of her son Aeneas, Aphrodite never managed to forget about the Argive spear that had once pierced her flesh in the fields of Troy. She helped Aegialia to obtain not one, but many lovers. (According to different traditions, Aegialia was living in adultery with Hippolytus, Cometes or Cyllabarus.)[33]

In any case Aegialia, being helped by the Argives, prevented Diomedes from entering the city. Or else, if he ever entered Argos, he had to take sanctuary at the altar of Hera, and thence flee with his companions by night.[34] Cometes was shortly the king of Argos, in Diomedes' absence, but was quickly replaced by the rightful heir, Cyanippus, who was the son of Aegialeus.

Life in Italy edit

Diomedes then migrated to Aetolia, and thence to Daunia (Apulia) in Italy. He went to the court of King Daunus, King of the Daunians. The king was honored to accept the great warrior. He begged Diomedes for help in warring against the Messapians, for a share of the land and marriage to his daughter. Diomedes agreed to the proposal, drew up his men and routed the Messapians. He took his land which he assigned to the Dorians, his followers. The two nations 'Monadi' and the 'Dardi' were vanquished by Diomedes along with the two cities of 'Apina' and 'Trica'.[35]

Diomedes later married Daunus's daughter Euippe and had two sons named Diomedes and Amphinomus. Some say that, after the sack of Troy, Diomedes came to Libya (due to a storm), where he was put in prison by King Lycus (who planned on sacrificing him to Ares). It is said that it was the king's daughter Callirrhoe, loosing Diomedes from his bonds, saved him. Diomedes is said to have sailed away without the least acknowledgment of the girl's kindly deed, whereupon she killed herself, out of grief, with a halter.[36]

Cities founded by Diomedes edit

The Greeks and Romans credited Diomedes with the foundation of several Greek settlements in Magna Graeca in southern Italy:[37] Argyrippa or Arpi, Aequum Tuticum (Ariano Irpino), Beneventum (Benevento), Brundusium (Brindisi), Canusium (Canosa), Venafrum (Venafro), Salapia, Spina, Garganum, Sipus (near Santa Maria di Siponto),[38] Histonium (Vasto), and Aphrodisia or Venusia (Venosa). The last was made as a peace-offering to the goddess, including temples in her honor.[39]

Virgil's Aeneid describes the beauty and prosperity of Diomedes' kingdom. When war broke out between Aeneas and Turnus, Turnus tried to persuade Diomedes to aid them in the war against the Trojans. Diomedes told them he had fought enough Trojans in his lifetime and urged Turnus that it was best to make peace with Aeneas than to fight the Trojans. He also said that his purpose in Italy is to live in peace.[40] Venulus, one of Latinus' messengers, recalls the mission to Diomedes after they seek his help in the war against the Rutulians. He states that when he found Diomedes, he was laying the foundations of his new city, Argyrippa.[41] Diomedes eventually speaks and states that, as punishment for his involvement at Troy, he never reached his fatherland of Argos and that he never saw his beloved wife again. The hero also states that birds pursue him and his soldiers, birds which used to be his companions and cry out everywhere they land, including the sea cliffs.[41] Ovid, on the other hand, writes that Venulus came to the home of exiled Diomedes in vain, but he was erecting walls with the favour of Iapygian Daunus, his new father-in-law, which would make the city Luceria, not Argyrippa.[42]

The worship and service of gods and heroes was spread by Diomedes far and wide : in and near Argos he caused temples of Athena to be built.[43] His armour was preserved in a temple of Athena at Luceria in Apulia, and a gold chain of his was shown in a temple of Artemis in Peucetia. At Troezene he had founded a temple of Apollo Epibaterius and instituted the Pythian games there.[44] Other sources claim that Diomedes had one more meeting with his old enemy Aeneas where he gave the Palladium back to the Trojans.

Hero cult of Diomedes edit

Hero cults became much more commonplace from the beginning of the 8th century onwards, and they were widespread throughout several Greek cities in the Mediterranean by the last quarter of the century. Diomedes' cults were situated predominantly in Cyprus, Metapontum, and other cities on the coast of the Adriatic sea (The archaeological evidence for the hero cult of Diomedes comes mostly from this area). There are also vestiges of this cult in areas like Cyprus and some mainland Greek cities, given the inscriptions on votive offerings found in temples and tombs, but the popularity is most evident along the Eastern coast of Italy. This cult reached so far East in the Mediterranean due to the Achaean migration during the 8th century.[45] The most distinct votive offerings to the hero were actually found within the island of Palagruža on the Adriatic.[46]

Strabo claims that the votive offerings in the Daunian temple of Athena at Luceria contained votive offerings specifically addressing Diomedes.[47]

Diomedes was worshipped as a hero not only in Greece, but on the coast of the Adriatic, as at Thurii and Metapontum. At Argos, his native place, during the festival of Athena, his shield was carried through the streets as a relic, together with the Palladium, and his statue was washed in the river Inachus.[48]

There were two islands named after the hero, Islands of Diomedes, believed to be in the Palagruža archipelago on the Adriatic. Strabo mentions that one was uninhabited. A passage in Aelian's On Animals explains the significance of this island and the mysterious birds which inhabit it. Strabo reflects on the peculiarities of this island, including the history tied to Diomedes' excursions and the regions and peoples among which he had the most influence. He writes that Diomedes himself had sovereignty over the areas around the Adriatic, citing the islands of Diomedes as proof of this, as well as the various tribes of people who worshiped him even in contemporary times, including the Heneti and the Dauni. The Heneti sacrificed a white horse to Diomedes in special groves where wild animals grew tame.[49]

This cult was not widespread; cults like those of Herakles and Theseus had a much more prominent function in the Greek world due to the benefits which they granted their followers and the popular mythological traditions of these figures.

Death edit

Strabo lists four different traditions about the hero's life in Italy. For one, he claims that at the city of Urium, Diomedes was making a canal to the sea when he was summoned home to Argos. He left the city and his undertakings half-finished and went home where he died. The second tradition claims the opposite, that he stayed at Urium until the end of his life. The third tradition claims he disappeared on Diomedea, the uninhabited island (called after him) in the Adriatic where the Shearwaters who were formerly his companions live, which implies some kind of deification. The fourth tradition comes from the Heneti, who claim Diomedes stayed in their country and eventually had a mysterious apotheosis.[47]

One Legend says that on his death, the albatrosses got together and sang a song (their normal call). Others say his companions were turned into birds afterwards. The family name for albatrosses, Diomedeidae, and the genus name for the great albatrosses, Diomedea, originate from Diomedes.[50]

On San Nicola Island of the Tremiti Archipelago there is a Hellenic period tomb called Diomedes's Tomb. According to a legend, the goddess Venus seeing the men of Diomedes cry so bitterly transformed them into birds (Diomedee) so that they could stand guard at the grave of their king. In Fellini's movie 8½, a cardinal tells this story to actor Marcello Mastroianni.[citation needed]

Immortality edit

According to the post Homeric stories, Diomedes was given immortality by Athena, which she had not given to his father. Pindar mentions the hero's deification in Nemean X, where he says "the golden-haired, gray-eyed goddess made Diomedes an immortal god."

In order to attain immortality, a scholiast for Nemean X says Diomedes married Hermione, the only daughter of Menelaus and Helen, and lives with the Dioscuri as an immortal god while also enjoying honours in Metapontum and Thurii.[51]

He was worshipped as a divine being under various names in Italy where statues of him existed at Argyripa, Metapontum, Thurii, and other places. There was a temple consecrated to Diomedes called 'The Timavo' at the Adriatic.[52] There are traces in Greece also of the worship of Diomedes.

The first two traditions listed by Strabo give no indication of divinity except later through a hero cult, and the other two declare strongly for Diomedes' immortality as more than a mere cult hero.

Afterlife edit

There are less known versions of Diomedes' afterlife. A drinking song to Harmodius, one of the famous tyrannicides of Athens, includes a reference to Diomedes as an inhabitant of the Islands of the Blessed, along with Achilles and Harmodius.[53]

In his Inferno, Dante sees Diomedes in the Eighth Circle of Hell, where the "counsellors of fraud" are imprisoned for eternity in sheets of flame. His offenses include advising the theft of the Palladium and, of course, the stratagem of the Trojan Horse. The same damnation is imposed on Odysseus, who is also punished for having persuaded Achilles to fight in the Trojan war, without telling him that this would inevitably lead to his death.

The Troilus and Cressida legend edit

Diomedes plays an important role in the medieval legend of Troilus and Cressida, in which he becomes the girl's new lover when she is sent to the Greek camp to join her traitorous father. In Shakespeare's play Troilus and Cressida, Diomedes is often seen fighting Troilus over her.

See also edit

- 1437 Diomedes, a minor asteroid

- Diomedes of Thrace

- HMS Diomede—four British ships named after Diomedes

- USS Diomedes

References edit

- ^ a b Jones, Daniel; Roach, Peter, James Hartman and Jane Setter, eds. Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary. 17th edition. Cambridge UP, 2006.

- ^ Dares Phrygius, History of the Fall of Troy13

- ^ Apollodorus 3.6

- ^ Apollodorus 3.7

- ^ Oxford Classical Dictionary, s.v. Adrastus

- ^ a b Tzetz. ad Lycoph. 993 ; Dict. Cret. iv. 3.

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae 81.

- ^ Apollodorus, Epitome E.3.3

- ^ Dictys Cretensis, Journal of the Trojan War 1.20

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae 98

- ^ Pseudo-Apollodorus, Epitome 3.21-2

- ^ Euripides, Iphigenia at Taurus 24–25

- ^ Aeneid II.82–99

- ^ Cypria testimonium 30 [Bernabé] = Pausanias 10.31.2

- ^ "Cypria" fragment 27. Greek Epic Fragments: From the Seventh to the Fifth Centuries BC, translated by M.L. West (Loeb Classical Library, 2003), 105.

- ^ Dict. Cret. ii. 15 ; comp. Paus. x. 31. § 1.

- ^ D.B. Monro (ed.), The Iliad: Books I-XII, p. 309

- ^ Iliad 13.277–278

- ^ Nassos Papalexandrou, The Visual Poetics of Power: Warriors, Youths, and Tripods in Early Greece [Lanham: Lexington Books, 2005], 28–29

- ^ "Aethiopis" argument 4. Greek Epic Fragments, 113.

- ^ Dict. Cret. v. 4

- ^ "Little Iliad" argument 4. Greek Epic Fragments, 123.

- ^ Virg. Aen. ii. 163

- ^ Eustath. ad Hom. p. 822.

- ^ Plato, Republic 493D

- ^ Aristophanes, Ecclesiazusae 1029; Plato, Republic 493D; Zenobius 3.8.

- ^ Plut. Quaest. Graec. 48.

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece I.28.9.

- ^ Serv. ad Aen. ii. 166, iii. 407, iv, 427, v. 81.

- ^ "Little Iliad" argument 24. Greek Epic Fragments, 137.

- ^ Scholia to Euripides Hecuba 41

- ^ "Returns" argument 1. Greek Epic Fragments, 155.

- ^ Dictys Cretensis 6. 2; Tzetzes on Lycophron 609; Servius on Aeneid 8. 9.

- ^ Tzetzes on Lycophron 602

- ^ Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, III. 16.—The Second Region of Italy.

- ^ Plut. Parall. Gr. et Rom. 23.

- ^ Anna Pasqualini (1998). "Diomede nel Lazio e le tradizioni leggendarie sulla fondazione di Lanuvio". Mélanges de l'École française de Rome. Antiquité. 110 (2). Roma: 663–679. doi:10.3406/mefr.1998.2048. ISSN 0223-5102.

- ^ Serv. ad Aen viii. 9, xi. 246; Strab. vi. pp. 283, 284; Plin. H. N. iii. 20; Justin, xii. 2.

- ^ Serv. on Verg. A. 11.246.

- ^ Paus. i. 11; Serv. ad Aen. viii. 9.

- ^ a b Virgil, Aeneid XI.246–247.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses XIV.457.

- ^ Plut. de Flum. 18; Paus. ii. 24. § 2

- ^ Schol. ad Pind. Nem. x. 12 ; Scylax, Peripl. p. 6; comp. Strab. v. p. 214, &c.

- ^ Farnell, Lewis Richard. Greek Hero Cults and Ideas of Immortality. Chicago: Ares Publishers Inc., 1921: 290)

- ^ Robert Parker, On Greek Religion (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2011): 245.

- ^ a b Strabo, Geography 6.3.9. Translated by Horace Leonard Jones. Loeb Classical Press, 1923.

- ^ Callimachus, Λοετρὰ Παλλάδος, line 35., Farnell 1921: 290.

- ^ Strabo, Geography 5.1.9. Translated by Horace Leonard Jones. Loeb Classical Press, 1923.

- ^ Gotch, A. F. (1995) [1979]. "Albatrosses, Fulmars, Shearwaters, and Petrels". Latin Names Explained. A Guide to the Scientific Classifications of Reptiles, Birds & Mammals. New York, NY: Facts on File. p. 190. ISBN 0-8160-3377-3.

- ^ J.B. Bury, Pindar: Nemean Odes (Amsterdam: Adolf M. Hakkert, 1965), 199.

- ^ Strabo, Geography 5.1.9

- ^ Skolion 894. Taken from Nagy 1999: 197.

Further reading edit

- Barbara, Sébastien (2023). Diomède outre-mer. sur les traces d’un héros grec en Occident. Paris: Les Belles Lettres. ISBN 9782251454375.

- Šašel Kos, Marjeta. “The Story of the Grateful Wolf and Venetic Horses in Strabo’s Geography". In: Studia Mythologica Slavica 11 (October). Ljubljana, Slovenija. 2008. pp. 9–24. The Story of the Grateful Wolf and Venetic Horses in Strabo’s GeographyPripovedka o hvaležnem volku in venetskih konjih v Strabonovi Geografiji.