This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

A credit card is a payment card, usually issued by a bank, allowing its users to purchase goods or services or withdraw cash on credit. Using the card thus accrues debt that has to be repaid later.[1] Credit cards are one of the most widely used forms of payment across the world.[2]

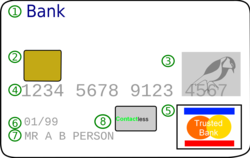

- Issuing bank logo

- EMV chip (only on "smart cards")

- Hologram

- Card number

- Card network logo

- Expiration date

- Card holder name

- Contactless chip

A regular credit card is different from a charge card, which requires the balance to be repaid in full each month or at the end of each statement cycle.[3] In contrast, credit cards allow the consumers to build a continuing balance of debt, subject to interest being charged. A credit card differs from a charge card also in that a credit card typically involves a third-party entity that pays the seller and is reimbursed by the buyer, whereas a charge card simply defers payment by the buyer until a later date. A credit card also differs from a debit card, which can be used like currency by the owner of the card.

As of June 2018,[update] there were 7.753 billion credit cards in the world.[4] In 2020, there were 1.09 billion credit cards in circulation in the U.S and 72.5% of adults (187.3 million) in the country had at least one credit card.[5][6][7][8]

Technical specifications edit

The size of most credit cards is 85.60 by 53.98 millimetres (3+3⁄8 in × 2+1⁄8 in) and rounded corners with a radius of 2.88–3.48 millimetres (9⁄80–11⁄80 in)[9] conforming to the ISO/IEC 7810 ID-1 standard, the same size as ATM cards and other payment cards, such as debit cards.[10] Most credit cards are made of plastic, but some are made from metal.[11][12]

Credit cards have a printed[13] or embossed bank card number complying with the ISO/IEC 7812 numbering standard. The card number's prefix, called the Bank Identification Number (known in the industry as a BIN[14]), is the sequence of digits at the beginning of the number that determine the bank to which a credit card number belongs. This is the first six digits for MasterCard and Visa cards. The next nine digits are the individual account number, and the final digit is a validity check digit.[15]

Both of these standards are maintained and further developed by ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 17/WG 1. Credit cards have a magnetic stripe conforming to the ISO/IEC 7813. Most modern credit cards use smart card technology: they have a computer chip embedded in them as a security feature. In addition, complex smart cards, including peripherals such as a keypad, a display or a fingerprint sensor are increasingly used for credit cards.[citation needed]

In addition to the main credit card number, credit cards also carry issue and expiration dates (given to the nearest month), as well as extra codes such as issue numbers and security codes. Complex smart cards allow to have a variable security code, thus increasing security for online transactions. Not all credit cards have the same sets of extra codes nor do they use the same number of digits.[citation needed]

Credit card numbers and cardholder names were originally embossed, to allow for easy transfer of such information to charge slips printed on carbon paper forms. With the decline of paper slips, some credit cards are no longer embossed and in fact the card number is no longer in the front.[16] In addition, some cards are now vertical in design, rather than horizontal.

History edit

Edward Bellamy's Looking Backward edit

The concept of using a card for purchases was described in 1887 by Edward Bellamy in his utopian novel Looking Backward.[17] Bellamy used the term credit card eleven times in this novel, although this referred to a card for spending a guaranteed minimum income, rather than borrowing,[18] making it more similar to a debit card.

Early charge coins and cards edit

Beginning in the late 19th century, charge cards came in various shapes and sizes, made of celluloid (an early type of plastic), copper, aluminum, steel, and other types of whitish metals.[19] Some were shaped like coins, with a little hole enabling it to be put in a key ring. These charge coins were usually given to customers who had charge accounts in hotels or department stores. Each had a charge account number, along with the merchant's name and logo.

The charge coin offered a simple and fast way to copy a charge account number to the sales slip, by imprinting the coin onto the sales slip.[20][21] The Charga-Plate, developed in 1928, was an early predecessor of the credit card and was used in the U.S. from the 1930s to the late 1950s. It was a 2+1⁄2-by-1+1⁄4-inch (64 mm × 32 mm) rectangle of sheet metal related to Addressograph and military dog tag systems. It was embossed with the customer's name, city, and state. It held a small paper card on its back for a signature. In recording a purchase, the plate was laid into a recess in the imprinter, with a paper "charge slip" positioned on top of it. The record of the transaction included an impression of the embossed information, made by the imprinter pressing an inked ribbon against the charge slip.[22] Charga-Plate was a trademark of Farrington Manufacturing Co.[23] Charga-Plates were issued by large-scale merchants to their regular customers, much like department store credit cards of today. In some cases, the plates were kept in the issuing store rather than held by customers. When an authorized user made a purchase, a clerk retrieved the plate from the store's files and then processed the purchase. Charga-Plates sped up back-office bookkeeping and reduced copying errors that were done manually in paper ledgers in each store.

Air Travel Card edit

In 1934, American Airlines and the Air Transport Association simplified the process even more with the advent of the Air Travel Card.[24] They created a numbering scheme that identified the issuer of the card as well as the customer account. This is the reason the modern UATP cards still start with the number 1. With an Air Travel Card, passengers could "buy now, and pay later" for a ticket against their credit and receive a fifteen percent discount at any of the accepting airlines. By the 1940s, all of the major U.S. airlines offered Air Travel Cards that could be used on 17 different airlines. By 1941, about half of the airlines' revenues came through the Air Travel Card agreement. The airlines had also started offering installment plans to lure new travellers into the air. In 1948, the Air Travel Card became the first internationally valid charge card within all members of the International Air Transport Association.[25]

Early general purpose charge cards: Diners Club, Carte Blanche, and American Express edit

The concept of customers paying different merchants using the same card was expanded in 1950 by Ralph Schneider and Frank McNamara, founders of Diners Club, to consolidate multiple cards. The Diners Club, which was created partially through a merger with Dine and Sign, produced the first "general purpose" charge card and required the entire bill to be paid with each statement. That was followed by Carte Blanche and in 1958 by American Express which created a worldwide credit card network (although these were initially charge cards that later acquired credit card features).

BankAmericard and Master Charge edit

Until 1958, no one had been able to successfully establish a revolving credit financial system in which a card issued by a third-party bank was being generally accepted by a large number of merchants, as opposed to merchant-issued revolving cards accepted by only a few merchants. There had been a dozen attempts by small American banks, but none of them were able to last very long. In 1958, Bank of America launched the BankAmericard in Fresno, California, which would become the first successful recognizably modern credit card.[26] This card succeeded where others failed by breaking the chicken-and-egg cycle in which consumers did not want to use a card that few merchants would accept and merchants did not want to accept a card that few consumers used. Bank of America chose Fresno because 45% of its residents used the bank, and by sending a card to 60,000 Fresno residents at once, the bank was able to convince merchants to accept the card.[1] It was eventually licensed to other banks around the United States and then around the world, and in 1976, all BankAmericard licensees united themselves under the common brand Visa. In 1966, the ancestor of MasterCard was born when a group of banks established Master Charge to compete with BankAmericard; it received a significant boost when Citibank merged its own Everything Card, launched in 1967, into Master Charge in 1969.

Early credit cards in the U.S., of which BankAmericard was the most prominent example, were mass-produced and mass mailed unsolicited to bank customers who were thought to be low risk. According to LIFE, cards were "mailed off to unemployable people, drunks, narcotics addicts and to compulsive debtors," which Betty Furness, President Johnson's Special Assistant, compared to "giving sugar to diabetics."[27] These mass mailings were known as "drops" in banking terminology, and were outlawed in 1970 due to the financial chaos they caused. However, by the time the law came into effect, approximately 100 million credit cards had been dropped into the U.S. population. After 1970, only credit card applications could be sent unsolicited in mass mailings.

This system was computerized in 1973 under the leadership of Dee Hock, the first CEO of Visa, allowing reduced transaction time.[28] However, until always-connected payment terminals became ubiquitous at the beginning of the 21st century, it was common for a merchant to accept a charge, especially below a threshold value or from a known and trusted customer, without verifying it by phone. Books with lists of stolen card numbers were distributed to merchants who were supposed in any case to check cards against the list before accepting them, as well as verifying the signature on the charge slip against that on the card. Merchants who failed to take the time to follow the proper verification procedures were liable for fraudulent charges, but because of the cumbersome nature of the procedures, merchants would often simply skip some or all of them and assume the risk for smaller transactions.

Development outside North America edit

The fragmented nature of the U.S. banking system regulation under the Glass–Steagall Act meant that credit cards became an effective way for those who were travelling around the country to move their credit to places where they could not directly use their banking facilities. There are now countless variations on the basic concept of revolving credit for individuals (as issued by banks and honored by a network of financial institutions), including organization-branded credit cards, corporate-user credit cards and store cards. In 1966, Barclaycard in the United Kingdom launched the first credit card outside the United States.

Although credit cards reached very high adoption levels in the U.S., Canada, the U.K., Australia, and New Zealand during the latter 20th century, many cultures were more cash-oriented or developed alternative forms of cashless payments, such as Carte bleue or the Eurocard (Germany, France, Switzerland, and others). In these places, the adoption of credit cards was initially much slower.[29] Due to strict regulations regarding bank overdrafts, some countries, France in particular, were much quicker to develop and adopt chip-based credit cards which are seen as major anti-fraud credit devices. Debit cards, online banking, ATMs, mobile banking, and installment plans are used more widely than credit cards in some countries. It took until the 1990s to reach anything like the percentage market penetration levels achieved in the U.S., Canada, and U.K. In some countries, acceptance still remains low as the use of a credit card system depends on the banking system of each country; while in others, a country sometimes had to develop its own credit card network, e.g. U.K.'s Barclaycard and Australia's Bankcard. Japan remains a very cash-oriented society, with credit card adoption being limited mainly to the largest of merchants; although stored value cards (such as telephone cards) are used as alternative currencies, the trend is toward RFID-based systems inside cards, cellphones, and other objects.

Design and vintage credit cards as collectibles edit

The design of the credit card itself has become a major selling point in recent years.[30] A growing field of numismatics (study of money), or more specifically exonumia (study of money-like objects), credit card collectors seek to collect various embodiments of credit from the now familiar plastic cards to older paper merchant cards, and even metal tokens that were accepted as merchant credit cards. Early credit cards were made of celluloid plastic, then metal and fiber, then paper, and are now mostly polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastic. However, the chip part of credit cards is made from metals.[31]

Cash advance edit

A cash advance is a credit card transaction that withdraws cash rather than purchasing something. The process can take place either through an ATM or over the counter at a bank or other financial agency, up to a certain limit; for a credit card, this will be the credit limit (or some percentage of it). Cash advances often incur a fee of 3 to 5 percent of the amount being borrowed. When made on a credit card, the interest is often higher than other credit card transactions. The interest compounds daily starting from the day cash is borrowed.[32]

Some purchases made with a credit card of items that are viewed as cash are also considered to be cash advances in accordance with the credit card network's guidelines, thereby incurring the higher interest rate and the lack of the grace period.[33] These often include money orders, prepaid debit cards, lottery tickets, gaming chips, mobile payments[32] and certain taxes and fees paid to certain governments. However, should the merchant not disclose the actual nature of the transactions, these will be processed as regular credit card transactions. Many merchants have passed on the credit card processing fees to the credit card holders in spite of the credit card network's guidelines, which state the credit card holders should not have any extra fee for doing a transaction with a credit card.

Under card scheme rules, a credit card holder presenting an accepted form of identification must be issued a cash advance over the counter at any bank which issues that type of credit card, even if the cardholder cannot give their PIN.

A Japanese law enabling credit card cash back came into force in 2010. However, a legal loophole in this system was quickly exploited by online shops dedicated to providing cash back as a form of easy loan with exorbitant rates. At first, the online store sells a single inexpensive item of glass marble, golf tee, or eraser with an 80,000 yen wire transfer for a 100,000 yen (1,200 US dollar) credit card payment. A month later, when the credit card provider charges the card owner with the full fee, the online store is out of the picture with no liability. In effect, what the online cash back services provide are loans with a 300% annual interest rate. On 19 October 2010, Hideki Fukuba became the first operator of such an online cash back service to be charged by the police. He was charged on tax evasion of 40 million yen in unpaid taxes.[34][35][36][relevant?]

Usage edit

A credit card issuing company, such as a bank or credit union, enters into agreements with merchants for them to accept their credit cards. Merchants often advertise in signage or other company material which cards they accept by displaying acceptance marks generally derived from logos. Alternatively, this may be communicated, for example, via a restaurant's menu or orally, or stating, "We don't take credit cards".

The credit card issuer issues a credit card to a customer at the time or after an account has been approved by the credit provider, which need not be the same entity as the card issuer. The cardholders can then use it to make purchases at merchants accepting that card. When a purchase is made, the cardholder agrees to pay the card issuer. The cardholder indicates consent to pay by signing a receipt with a record of the card details and indicating the amount to be paid or by entering a personal identification number (PIN). Also, many merchants now accept verbal authorizations via telephone and electronic authorization using the Internet, known as a card not present transaction (CNP).

Electronic verification systems allow merchants to verify in a few seconds that the card is valid and the cardholder has sufficient credit to cover the purchase, allowing the verification to happen at time of purchase. The verification is performed using a credit card payment terminal or point-of-sale (POS) system with a communications link to the merchant's acquiring bank. Data from the card is obtained from a magnetic stripe or chip on the card; the latter system is called Chip and PIN in the United Kingdom and Ireland, and is implemented as an EMV card.

For card not present transactions where the card is not shown (e.g., e-commerce, mail order, and telephone sales), merchants additionally verify that the customer is in physical possession of the card and is the authorized user by asking for additional information such as the security code printed on the back of the card, date of expiry, and billing address.

Each month, the cardholder is sent a statement indicating the purchases made with the card, any outstanding fees, the total amount owed and the minimum payment due. In the U.S., after receiving the statement, the cardholder may dispute any charges that are thought to be incorrect (see 15 U.S.C. § 1643, which limits cardholder liability for unauthorized use of a credit card to $50). The Fair Credit Billing Act gives details of the U.S. regulations.

Many banks now also offer the option of electronic statements, either in lieu of or in addition to physical statements, which can be viewed at any time by the cardholder via the issuer's online banking website. Notification of the availability of a new statement is generally sent to the cardholder's email address. If the card issuer has chosen to allow it, the cardholder may have other options for payment besides a physical check, such as an electronic transfer of funds from a checking account. Depending on the issuer, the cardholder may also be able to make multiple payments during a single statement period, possibly enabling him or her to utilize the credit limit on the card several times.

Minimum payment edit

The cardholder must pay a defined minimum portion of the amount owed by a due date or may choose to pay a higher amount. The credit issuer charges interest on the unpaid balance if the billed amount is not paid in full (typically at a much higher rate than most other forms of debt). This impact accounts for roughly 8% of all interest ever paid. Thus, hiding the minimum payment option for automatic and manual payments and focusing on the total debt may mitigate the unwanted consequences of default minimum payments.[37] In addition, if the cardholder fails to make at least the minimum payment by the due date, the issuer may impose a late fee or other penalties. To help mitigate this, some financial institutions can arrange for automatic payments to be deducted from the cardholder's bank account, thus avoiding such penalties altogether, as long as the cardholder has sufficient funds.

In cases where the minimum payment is less than the finance charges and fees assessed during the billing cycle, the outstanding balance will increase in what is called negative amortization. This practice tends to increase credit risk and mask the lender's portfolio quality and consequently has been banned in the U.S. since 2003.[38][39]

Advertising, solicitation, application and approval edit

Credit card advertising regulations in the U.S. include the Schumer box disclosure requirements. A large fraction of junk mail consists of the credit card offers created from lists provided by the major credit reporting agencies. In the United States, the three major U.S. credit bureaus (Equifax, TransUnion and Experian) allow consumers to opt out from related credit card solicitation offers via its Opt Out Pre Screen program.

Interest charges edit

Credit card issuers usually waive interest charges if the balance is paid in full each month, but typically will charge full interest on the entire outstanding balance from the date of each purchase if the total balance is not paid.

For example, if a user had a $1,000 transaction and repaid it in full within this grace period, there would be no interest charged. If, however, even $1.00 of the total amount remained unpaid, interest would be charged on the $1,000 from the date of purchase until the payment is received. The precise manner in which interest is charged is usually detailed in a cardholder agreement which may be summarized on the back of the monthly statement. The general calculation formula most financial institutions use to determine the amount of interest to be charged is (APR/100 x ADB)/365 x number of days revolved. Take the annual percentage rate (APR) and divide by 100 then multiply to the amount of the average daily balance (ADB). Divide the result by 365 and then take this total and multiply by the total number of days the amount revolved before payment was made on the account. Financial institutions refer to interest charged back to the original time of the transaction and up to the time a payment was made, if not in full, as a residual retail finance charge (RRFC). Thus after an amount has revolved and a payment has been made, the user of the card will still receive interest charges on their statement after paying the next statement in full (in fact the statement may only have a charge for interest that collected up until the date the full balance was paid, i.e. when the balance stopped revolving).

The credit card may simply serve as a form of revolving credit, or it may become a complicated financial instrument with multiple balance segments each at a different interest rate, possibly with a single umbrella credit limit, or with separate credit limits applicable to the various balance segments. Usually, this compartmentalization is the result of special incentive offers from the issuing bank, to encourage balance transfers from cards of other issuers. If several interest rates apply to various balance segments, then payment allocation is generally at the discretion of the issuing bank, and payments will therefore usually be allocated towards the lowest rate balances until paid in full before any money is paid towards higher rate balances. Interest rates can vary considerably from card to card, and the interest rate on a particular card may jump dramatically if the card user is late with a payment on that card or any other credit instrument, or even if the issuing bank decides to raise its revenue.[citation needed]

Grace period edit

A credit card's grace period[40][32] is the time the cardholder has to pay the balance before interest is assessed on the outstanding balance. Grace periods may vary but usually range from 20 to 55 days depending on the type of credit card and the issuing bank. Some policies allow for reinstatement after certain conditions are met. Usually, if a cardholder is late paying the balance, finance charges will be calculated and the grace period does not apply. Finance charges incurred depend on the grace period and balance; with most credit cards there is no grace period if there is any outstanding balance from the previous billing cycle or statement (i.e. interest is applied on both the previous balance and new transactions). However, there are some credit cards that will only apply finance charges on the previous or old balance, excluding new transactions.

Parties involved edit

- Cardholder: The holder of the card used to make a purchase; the consumer. Do not pay fraudulent charges on the US credit cards.

- Card-issuing bank: The financial institution or other organization that issued the credit card to the cardholder. This bank bills the consumer for repayment and bears the risk that the card is used fraudulently. American Express and Discover were previously the only card-issuing banks for their respective brands, but as of 2007, this is no longer the case. Cards issued by banks to cardholders in a different country are known as offshore credit cards. In the U.S., credit card issuers do not have to inform cardholders when they close any credit card even cards with balances.

- Merchant: The individual or business accepting credit card payments for products or services sold to the cardholder.

- Acquiring bank: The financial institution accepting payment for the products or services on behalf of the merchant.

- Independent sales organization: Re-sellers (to merchants) of the services of the acquiring bank.

- Merchant account: This could refer to the acquiring bank or the independent sales organization, but in general is the organization that the merchant deals with.

- Card association: An association of card-issuing banks such as Discover, Visa, MasterCard, American Express, etc. that set transaction terms for merchants, card-issuing banks, and acquiring banks.

- Transaction network: The system that implements the mechanics of electronic transactions. May be operated by an independent company, and one company may operate multiple networks.

- Affinity partner: Some institutions lend their names to an issuer to attract customers that have a strong relationship with that institution, and get paid a fee or a percentage of the balance for each card issued using their name. Examples of typical affinity partners are sports teams, universities, charities, professional organizations, and major retailers.

- Insurance providers: Insurers underwriting various insurance protections offered as credit card perks, for example, Car Rental Insurance, Purchase Security, Hotel Burglary Insurance, Travel Medical Protection etc.

The flow of information and money between these parties—always through the card associations—is known as the interchange, and it consists of a few steps.

Transaction steps edit

- Authorization: The cardholder presents the card as payment to the merchant and the merchant submits the transaction to the acquirer (acquiring bank). The acquirer verifies the credit card number, the transaction type and the amount with the issuer (card-issuing bank) and reserves that amount of the cardholder's credit limit for the merchant. An authorization will generate an approval code, which the merchant stores with the transaction.

- Batching: Authorized transactions are stored in "batches", which are sent to the acquirer. Batches are typically submitted once per day at the end of the business day. Batching can be done manually (initiated by a merchant's action) or automatically (on a pre-determined schedule, using a payment processing platform). If a transaction is not submitted in the batch, the authorization will stay valid for a period determined by the issuer, after which the held amount will be returned to the cardholder's available credit (see authorization hold). Some transactions may be submitted in the batch without prior authorizations; these are either transactions falling under the merchant's floor limit or ones where the authorization was unsuccessful but the merchant still attempts to force the transaction through. (Such may be the case when the cardholder is not present but owes the merchant additional money, such as extending a hotel stay or car rental.)

- Clearing and Settlement: The acquirer sends the batch transactions through the credit card association, which debits the issuers for payment and credits the acquirer. Essentially, the issuer pays the acquirer for the transaction.

- Funding: Once the acquirer has been paid, the acquirer pays the merchant. The merchant receives the amount totalling the funds in the batch minus either the "discount rate", "mid-qualified rate", or "non-qualified rate" which are tiers of fees the merchant pays the acquirer for processing the transactions.

- Chargebacks: A chargeback is an event in which money in a merchant account is held due to a dispute relating to the transaction. Chargebacks are typically initiated by the cardholder. In the event of a chargeback, the issuer returns the transaction to the acquirer for resolution. The acquirer then forwards the chargeback to the merchant, who must either accept the chargeback or contest it.

Credit card register edit

A credit card register is a transaction register used to ensure the increasing balance owed from using a credit card is enough below the credit limit to deal with authorization holds and payments not yet received by the bank and to easily look up past transactions for reconciliation and budgeting.

The register is a personal record of banking transactions used for credit card purchases as they affect funds in the bank account or the available credit. In addition to checking numbers and so forth the code column indicates the credit card. The balance column shows available funds after purchases. When the credit card payment is made the balance already reflects the funds were spent. In a credit card's entry, the deposit column shows the available credit and the payment column shows the total owed, their sum being equal to the credit limit.

Each check is written, debit card transaction, cash withdrawal, and credit card charge are entered manually into the paper register daily or several times per week.[41] Credit card register also refers to one transaction record for each credit card. In this case, the booklets readily enable the location of a card's current available credit when ten or more cards are in use. [citation needed]

Specialized types edit

Business credit cards edit

Business credit cards are specialized credit cards issued in the name of a registered business, and typically they can only be used for business purposes. Their use has grown in recent decades. In 1998, for instance, 37% of small businesses reported using a business credit card; by 2009, this number had grown to 64%.[42]

Business credit cards offer a number of features specific to businesses. They frequently offer special rewards in areas such as shipping, office supplies, travel, and business technology. Most issuers use the applicant's personal credit score when evaluating these applications. In addition, income from a variety of sources may be used to qualify, which means these cards may be available to businesses that are newly established.[43] In addition, some issuers of this card do not report account activity to the owner's personal credit, or only do so if the account is delinquent.[44] In these cases, the activity of the business is separated from the owner's personal credit activity.

Business credit cards are offered by American Express, Discover, and almost all major issuers of Visa and MasterCard cards. Some local banks and credit unions also offer business credit cards. American Express is the only major issuer of business charge cards in the United States, however.

Secured credit cards edit

A secured credit card is a type of credit card secured by a deposit account owned by the cardholder. Typically, the cardholder must deposit between 100% and 200% of the total amount of credit desired. Thus if the cardholder puts down $1,000, they will be given credit in the range of $500–1,000. In some cases, credit card issuers will offer incentives even on their secured card portfolios. In these cases, the deposit required may be significantly less than the required credit limit and can be as low as 10% of the desired credit limit. This deposit is held in a special savings account. Credit card issuers offer this because they have noticed that delinquencies were notably reduced when the customer perceives something to lose if the balance is not repaid.

The cardholder of a secured credit card is still expected to make regular payments, as with a regular credit card, but should they default on a payment, the card issuer has the option of recovering the cost of the purchases paid to the merchants out of the deposit. The advantage of the secured card for an individual with negative or no credit history is that most companies report regularly to the major credit bureaus. This allows the cardholder to start building (or re-building) a positive credit history.

Although the deposit is in the hands of the credit card issuer as security in the event of default by the consumer, the deposit will not be debited simply for missing one or two payments. Usually, the deposit is only used as an offset when the account is closed, either at the request of the customer or due to severe delinquency (150 to 180 days). This means that an account that is less than 150 days delinquent will continue to accrue interest and fees, and could result in a balance that is much higher than the actual credit limit on the card. In these cases, the total debt may far exceed the original deposit and the cardholder not only forfeits their deposit but is left with additional debt.

Most of these conditions are usually described in a cardholder agreement which the cardholder signs when their account is opened.

Secured credit cards are an option to allow a person with a poor credit history or no credit history to have a credit card that might not otherwise be available. They are often offered as a means of rebuilding one's credit. Fees and service charges for secured credit cards often exceed those charged for ordinary non-secured credit cards. For people in certain situations (for example, after charging off on other credit cards, or people with a long history of delinquency on various forms of debt), secured cards are almost always more expensive than unsecured credit cards.

Sometimes a credit card will be secured by the equity in the borrower's home.

Prepaid cards edit

They are sometimes called "prepaid credit card", but they are a debit card (prepaid card or prepaid debit card),[45] since no credit is offered by the card issuer: the cardholder spends money which has been "stored" via a prior deposit by the cardholder or someone else, such as a parent or employer. However, it carries a credit-card brand (such as Discover, Visa, MasterCard, American Express, or JCB) and can be used in similar ways just as though it were a credit card.[45] Unlike debit cards, prepaid credit cards generally do not require a PIN. An exception are prepaid credit cards with an EMV chip. These cards do require a PIN if the payment is processed via Chip and PIN technology. As of 2018, most debit cards in the U.S. were prepaid cards (71.7%).[8]

After purchasing the card, the cardholder loads the account with any amount of money, up to the predetermined card limit and then uses the card to make purchases the same way as a typical credit card. Prepaid cards can be issued to minors (above 13) since there is no credit line involved. The main advantage over secured credit cards (see above section) is that the cardholder is not required to come up with $500 or more to open an account. With prepaid credit cards, purchasers are not charged any interest but are often charged a purchasing fee plus monthly fees after an arbitrary time period. Many other fees also usually apply to a prepaid card.[45]

Prepaid credit cards are sometimes marketed to teenagers[45] for shopping online without having their parents complete the transaction.[46] Teenagers can only use funds that are available on the card which helps promote financial management to reduce the risk of debt problems later in life.[47]

Prepaid cards can be used globally. The prepaid card is convenient for payees in developing countries like Brazil, Russia, India, and China, where international wire transfers and bank checks are time-consuming, complicated and costly.[citation needed]

Because of the many fees that apply to obtaining and using credit-card-branded prepaid cards, the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada describes them as "an expensive way to spend your own money".[48] The agency publishes a booklet entitled Pre-paid Cards which explains the advantages and disadvantages of this type of prepaid card.see #Further reading

Digital cards edit

A digital card is a digital cloud-hosted virtual representation of any kind of identification card or payment card, such as a credit card.[49]

Charge cards edit

The charge cards are a type of credit card.

Benefits and drawbacks edit

Benefits to cardholder edit

The main benefit to the cardholder is convenience. Compared to debit cards and checks, a credit card allows small short-term loans to be quickly made to a cardholder who need not calculate a balance remaining before every transaction, provided the total charges do not exceed the maximum credit line for the card.

One financial benefit is that no interest is charged when the balance is paid in full within the grace period. In the United States, most credit cards offer a grace period (ex. 21, 23 or 25 days) on purchase transactions.

Different countries offer different levels of protection. In the U.K., for example, the bank is jointly liable with the merchant for purchases of defective products over £100.[50]

Many credit cards offer benefits to cardholders. Some benefits apply to products purchased with the card, like extended product warranties, reimbursement for decreases in price immediately after purchase (price protection), and reimbursement for theft or damage on recently purchased products (purchase protection).[51] Other benefits include various types of travel insurance, such as rental car insurance, travel accident insurance, baggage delay insurance, and trip delay or cancellation insurance.[52]

Credit cards may also offer a loyalty program, where each purchase is rewarded based on the price of the purchase. Typically, rewards are either in the form of cashback or points. Points are often redeemable for gift cards, products, or travel expenses like airline tickets. Some credit cards allow the transfer of accrued points to hotel and airline loyalty programs.[53] Research has examined whether competition among card networks may potentially make payment rewards too generous, causing higher prices among merchants, thus actually impacting social welfare and its distribution, a situation potentially warranting public policy interventions.[54]

Some countries, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and France, limit the amount for which a consumer can be held liable in the event of fraudulent transactions with a lost or stolen credit card.

Comparison of credit card benefits in the U.S. edit

The table below contains a list of benefits offered in the United States for consumer credit cards in some of these networks. These benefits may vary with each credit card issuer.

| MasterCard[55] | Visa[56] | American Express[57] | Discover[58] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Return extension | 60 days up to $250 |

90 days up to $250[59] |

90 days up to $300 |

Not Available[60] |

| Extended warranty | 2× original up to 1 year |

Depends | 1 additional year 6 years max | |

| Price protection | 60 days | Varies | ||

| Loss/damage coverage | 90 days | Depends | 90 days up to $1,000 | |

| Rental car insurance | 15 days: collision, theft, vandalism | 15 days: collision, theft | 30 days: collision, theft, vandalism[61] |

Detriments to cardholders edit

High interest and bankruptcy edit

Low introductory credit card rates are limited to a fixed term, usually between 6 and 12 months, after which a higher rate is charged. As all credit cards charge fees and interest, some customers become so indebted to their credit card provider that they are driven to bankruptcy. Some credit cards often levy a rate of 20 to 30 percent after a payment is missed.[62] In other cases, a fixed charge is levied without change to the interest rate. In some cases universal default may apply: the high default rate is applied to a card in good standing by missing a payment on an unrelated account from the same provider. This can lead to a snowball effect in which the consumer is drowned by unexpectedly high-interest rates. Further, most card holder agreements enable the issuer to arbitrarily raise the interest rate for any reason they see fit. First Premier Bank at one point offered a credit card with a 79.9% interest rate;[63] however, they discontinued this card in February 2011 because of persistent defaults.[64]

Research shows that a substantial fraction of consumers (about 40 percent) choose a sub-optimal credit card agreement, with some incurring hundreds of dollars of avoidable interest costs.[65]

Unnecessary risk edit

Credit card ownership brings additional risks with it (compared to other cashless payment alternatives) such as an increased risk of fraud,[66] or taking on unnecessary liability.

Weakens self regulation edit

Several studies have shown that consumers are likely to spend more money when they pay by credit card. Researchers suggest that when people pay using credit cards, they do not experience the abstract pain of payment.[67] Furthermore, researchers have found that using credit cards can increase consumption of unhealthy food, compared to using cash.[68]

Detriments to society edit

Inflated pricing for all consumers edit

Merchants that accept credit cards must pay interchange fees and discount fees on all credit card transactions.[69][70] In some cases merchants are barred by their credit agreements from passing these fees directly to credit card customers, or from setting a minimum transaction amount (no longer prohibited in the United States, United Kingdom or Australia).[71] The result is that merchants are induced to charge all customers (including those who do not use credit cards) higher prices to cover the fees on credit card transactions.[70] The inducement can be strong because the merchant's fee is a percentage of the sale price, which has a disproportionate effect on the profitability of businesses that have predominantly credit card transactions unless compensated for by raising prices generally. In the United States in 2008 credit card companies collected a total of $48 billion in interchange fees, or an average of $427 per family, with an average fee rate of about 2% per transaction.[70]

Credit card rewards result in a total transfer of $1,282 from the average cash payer to the average card payer per year.[72]

Benefits to merchants edit

For merchants, card-based purchase amounts reduce resistance compared to paying cash,[73] and the transaction is often more secure than other forms of payment, such as Checks, because the issuing bank commits to pay the merchant the moment the transaction is authorized, regardless of whether the consumer defaults on the credit card payment (except for legitimate disputes, which can result in charges back to the merchant). Cards are even more secure than cash because they reduce theft opportunities by reducing the amount of cash on the premises. Finally, credit cards reduce the back office expense of processing checks/cash and transporting them to the bank.

Prior to credit cards, each merchant had to evaluate each customer's credit history before extending credit. That task is now performed by the banks which assume the credit risk. Extra turnover is generated by the fact that the customer can purchase goods and services immediately and is less inhibited by the amount of cash in pocket and the immediate state of the customer's bank balance. Much of merchants' marketing is based on this immediacy. For each purchase, the bank charges the merchant a commission (discount fee) for this service and there may be a certain delay before the agreed payment is received by the merchant. The commission is often a percentage of the transaction amount, plus a fixed fee (interchange rate).[40]

Costs to merchants edit

Merchants are charged several fees for accepting credit cards. The merchant is usually charged a commission of around 0.5 to 4 percent of the value of each transaction paid for by credit card.[74] The merchant may also pay a variable charge, called a merchant discount rate, for each transaction.[69] In some instances of very low-value transactions, use of credit cards will significantly reduce the profit margin or cause the merchant to lose money on the transaction. Merchants with very low average transaction prices or very high average transaction prices are more averse to accepting credit cards. In some cases, merchants may charge users a "credit card supplement" (or surcharge), either a fixed amount or a percentage, for payment by credit card.[75] This practice was prohibited by most credit card contracts in the United States until 2013 when a major settlement between merchants and credit card companies allowed merchants to levy surcharges. Most retailers have not started using credit card surcharges, however, for fear of losing customers.[76]

Merchants in the United States have been fighting what they consider to be unfairly high fees charged by credit card companies in a series of lawsuits that started in 2005. Merchants charged that the two main credit card processing companies, MasterCard and Visa, used their monopoly power to levy excessive fees in a class-action lawsuit involving the National Retail Federation and major retailers such as Wal-Mart. In December 2013, a federal judge approved a $5.7 billion settlement in the case that offered payouts to merchants who had paid credit card fees, the largest antitrust settlement in U.S. history. Some large retailers, such as Wal-Mart and Amazon, chose to not participate in this settlement, however, and have continued their legal fight against the credit card companies.[76]

In April 2015 EU imposed a cap on the interchange fee to 0.3% on consumer credit cards, and 0.2% on debit cards.[77]

Merchants are also required to lease or purchase processing equipment, in some cases, this equipment is provided free of charge by the processor. Merchants must also satisfy data security compliance standards which are highly technical and complicated. In many cases, there is a delay of several days before funds are deposited into a merchant's bank account. Because credit card fee structures are very complicated, smaller merchants are at a disadvantage to analyze and predict fees.

Finally, merchants assume the risk of chargebacks by consumers.

Security edit

Credit card security relies on the physical security of the plastic card as well as the privacy of the credit card number. Therefore, whenever a person other than the card owner has access to the card or its number, security is potentially compromised. Once, merchants would often accept credit card numbers without additional verification for mail order purchases. It is now common practice to only ship to confirmed addresses as a security measure to minimize fraudulent purchases. Some merchants will accept a credit card number for in-store purchases, whereupon access to the number allows easy fraud, but many require the card itself to be present and require a signature (for magnetic stripe cards). A lost or stolen card can be cancelled, and if this is done quickly, will greatly limit the fraud that can take place in this way. European banks can require a cardholder's security PIN be entered for in-person purchases with the card.

The Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS) is the security standard issued by the Payment Card Industry Security Standards Council (PCI SSC). This data security standard is used by acquiring banks to impose cardholder data security measures upon their merchants.

The goal of the credit card companies is not to eliminate fraud, but to "reduce it to manageable levels".[78] This implies that fraud prevention measures will be used only if their cost is lower than the potential gains from fraud reduction, whereas high-cost low-return measures will not be used – as would be expected from organizations whose goal is profit maximization.

Internet fraud may be committed by claiming a chargeback which is not justified ("friendly fraud"), or carried out by the use of credit card information which can be stolen in many ways, the simplest being copying information from retailers, either online or offline. Despite efforts to improve security for remote purchases using credit cards, security breaches are usually the result of poor practice by merchants. For example, a website that safely uses TLS to encrypt card data from a client may then email the data, unencrypted, from the webserver to the merchant; or the merchant may store unencrypted details in a way that allows them to be accessed over the Internet or by a rogue employee; unencrypted card details are always a security risk. Even encrypted data may be cracked.

Controlled payment numbers (also known as virtual credit cards or disposable credit cards) are another option for protecting against credit card fraud where the presentation of a physical card is not required, as in telephone and online purchasing. These are one-time use numbers that function as a payment card and are linked to the user's real account, but do not reveal details, and cannot be used for subsequent unauthorized transactions. They can be valid for a relatively short time, and limited to the actual amount of the purchase or a limit set by the user. Their use can be limited to one merchant. If the number given to the merchant is compromised, it will be rejected if an attempt is made to use it a second time.

A similar system of controls can be used on physical cards. Technology provides the option for banks to support many other controls too that can be turned on and off and varied by the credit card owner in real time as circumstances change (i.e., they can change temporal, numerical, geographical and many other parameters on their primary and subsidiary cards). Apart from the obvious benefits of such controls: from a security perspective this means that a customer can have a Chip and PIN card secured for the real world, and limited for use in the home country. In this eventuality, a thief stealing the details will be prevented from using these overseas in non-chip and pin EMV countries. Similarly, the real card can be restricted from use online so that stolen details will be declined if this is tried. Then when card users shop online they can use virtual account numbers. In both circumstances, an alert system can be built in notifying a user that a fraudulent attempt has been made which breaches their parameters, and can provide data on this in real-time.

Additionally, there are security features present on the physical card itself in order to prevent counterfeiting. For example, most modern credit cards have a watermark that will fluoresce under ultraviolet light.[79] Most major credit cards have a hologram. A Visa card has a letter V superimposed over the regular Visa logo and a MasterCard has the letters MC across the front of the card. Older Visa cards have a bald eagle or dove across the front. In the aforementioned cases, the security features are only visible under ultraviolet light and are invisible in normal light.

In the United States, the United States Department of Justice, United States Secret Service, Federal Bureau of Investigation, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and U.S. Postal Inspection Service are responsible for prosecuting criminals who engage in credit card fraud.[80] However, they do not have the resources to pursue all criminals, and in general they only prosecute cases exceeding $5,000.

Three improvements to card security have been introduced to the more common credit card networks, but none has proven to help reduce credit card fraud so far. First, the cards themselves are being replaced with similar-looking tamper-resistant smart cards which are intended to make forgery more difficult. The majority of smart card (IC card) based credit cards comply with the EMV (Europay MasterCard Visa) standard. Second, an additional 3 or 4 digit card security code (CSC) or card verification value (CVV) is now present on the back of most cards, for use in card not present transactions. Stakeholders at all levels in electronic payment have recognized the need to develop consistent global standards for security that account for and integrate both current and emerging security technologies. They have begun to address these needs through organisations such as PCI DSS and the Secure POS Vendor Alliance.[81]

Code 10 edit

Code 10 calls are made when merchants are suspicious about accepting a credit card.

The operator then asks the merchant a series of yes-or-no questions to find out whether the merchant is suspicious of the card or the cardholder. The merchant may be asked to retain the card if it is safe to do so. The merchant may receive a reward for returning a confiscated card to the issuing bank, especially if an arrest is made.[82][83][84][85]

Costs and revenues of credit card issuers edit

Costs edit

- Charge offs: When a cardholder becomes severely delinquent on a debt,[86] the creditor may declare the debt to be a charge-off. It will then be listed as such on the debtor's credit bureau reports. (Equifax, for instance, lists "R9" in the "status" column to denote a charge-off.) A charge-off is considered to be "written off as uncollectible". To banks, bad debts and fraud are part of the cost of doing business.

- However, the debt is still legally valid, and the creditor can attempt to collect the full amount for the time periods permitted under state law, which is usually three to seven years. This includes contacts from internal collections staff, or more likely, an outside collection agency. If the amount is large (generally over $1,500–2,000), there is the possibility of a lawsuit or arbitration.

- Fraud: In relative numbers the values lost in bank card fraud are minor, calculated in 2006 at 7 cents per 100 dollars worth of transactions (7 basis points).[87] In 2004, in the U.K., the cost of fraud was over £500 million.[88] When a card is stolen, or an unauthorized duplicate made, most card issuers will refund some or all of the charges that the customer has received for things they did not buy. These refunds will, in some cases, be at the expense of the merchant, especially in mail order cases where the merchant cannot claim sight of the card. In several countries, merchants will lose money if no ID card was asked for, therefore merchants usually require ID cards in these countries. Credit card companies generally guarantee the merchant will be paid on legitimate transactions regardless of whether the consumer pays their credit card bill.

- Most banking services have their own credit card services that handle fraud cases and monitor for any possible attempt at fraud. Employees that are specialized in doing fraud monitoring and investigation are often placed in Risk Management, Fraud and Authorization, or Cards and Unsecured Business. Fraud monitoring emphasizes minimizing fraud losses while making an attempt to track down those responsible and contain the situation. Credit card fraud is a major white-collar crime that has been around for many decades, even with the advent of the chip-based card (EMV) that was put into practice in some countries to prevent cases such as these. Even with the implementation of such measures, credit card fraud continues to be a problem.

- Interest expenses: Banks generally borrow the money they then lend to their customers. As they receive very low-interest loans from other firms, they may borrow as much as their customers require, while lending their capital to other borrowers at higher rates. If the card issuer charges 15% on money lent to users, and it costs 5% to borrow the money to lend, and the balance sits with the cardholder for a year, the issuer earns 10% on the loan. This 10% difference is the "net interest spread" and the 5% is the "interest expense".

- Operating costs: This is the cost of running the credit card portfolio, including everything from paying the executives who run the company to printing the plastics, to mailing the statements, to running the computers that keep track of every cardholder's balance, to taking the many phone calls which cardholders place to their issuer, to protecting the customers from fraud rings. Depending on the issuer, marketing programs are also a significant portion of expenses.

- Rewards (programs) There is a cost to the issuer for these programs

Revenues edit

Interchange fee edit

In addition to fees paid by the card holder, merchants must also pay interchange fees to the card-issuing bank and the card association.[89][90] For a typical credit card issuer, interchange fee revenues may represent about a quarter of total revenues.[91]

These fees are typically from 1 to 6 percent of each sale but will vary not only from merchant to merchant (large merchants can negotiate lower rates[91]), but also from card to card, with business cards and rewards cards generally costing the merchants more to process. The interchange fee that applies to a particular transaction is also affected by many other variables including the type of merchant, the merchant's total card sales volume, the merchant's average transaction amount, whether the cards were physically present, how the information required for the transaction was received, the specific type of card, when the transaction was settled, and the authorized and settled transaction amounts. In some cases, merchants add a surcharge to the credit cards to cover the interchange fee, encouraging their customers to instead use cash, debit cards, or even cheques.

The 2022-proposed change in Interchange fees, by encouraging use of multiple card networks was criticized as likely to reduce fraud detection.[92]

Interest on outstanding balances edit

Interest charges vary widely from card issuer to card issuer. Often, there are "teaser" rates or promotional APR in effect for initial periods of time (as low as zero percent for, say, six months), whereas regular rates can be as high as 40 percent.[93] In the U.S. there is no federal limit on the interest or late fees credit card issuers can charge; the interest rates are set by the states, with some states such as South Dakota, having no ceiling on interest rates and fees, inviting some banks to establish their credit card operations there. Other states, for example Delaware, have very weak usury laws. The teaser rate no longer applies if the customer does not pay their bills on time, and is replaced by a penalty interest rate (for example, 23.99%) that applies retroactively.

Transactors and revolvors edit

Credit card analysts tag some accounts on a transactor (pays in full) or revolvor continuum. The issuer needs both types of cardholders; some pay interest, others primarily cause merchants to pay fees.

Revolving account edit

A revolving account is an account created by a financial institution to enable a customer to incur a debt, which is charged to the account, and in which the borrower does not have to pay the outstanding balance on that account in full every month. The borrower may be required to make a minimum payment, based on the balance amount. However, the borrower normally has the discretion to pay the lender any amount between the minimum payment and the full balance. If the balance is not paid in full by the end of a monthly billing period, the remaining balance will roll over or "revolve" into the next month. Interest will be charged on that amount and added to the balance.

A revolving account is a form of a line of credit, typically subject to a credit limit; not all credit cards have a credit limit.[94] The term can also refer to a for-emergencies savings fund.[95]

Fees charged to customers edit

The major credit card fees are for:

- Membership fees (annual or monthly), sometimes a percentage of the credit limit.

- Cash advances and convenience cheques (often 3% of the amount)

- Charges that result in exceeding the credit limit on the card (whether deliberately or by mistake), called over-limit fees

- Exchange rate loading fees (sometimes these might not be reported on the customer's statement, even when applied).[96] The variation of exchange rates applied by different credit cards can be very substantial, as much as 10% according to a Lonely Planet report in 2009.[97]

- Late or overdue payments

- Returned cheque fees or payment processing fees (e.g. phone payment fee)

- Transactions in a foreign currency (as much as 3% of the amount). A few financial institutions do not charge a fee for this.

- Finance charge is any charge that is included in the cost of borrowing money.[98]

Some card issuers charge customers who exceed a monthly usage cap (even if they pay off during the month and so never exceed their credit limit). And other issuers charge customers who overpay and so have a negative balance.[citation needed]

In the U.S., the Credit CARD Act of 2009 specifies that credit card companies must send cardholders a notice 45 days before they can increase or change certain fees. This includes annual fees, cash advance fees, and late fees.[99]

Controversy edit

One controversial area is the trailing interest issue. Trailing interest refers to interest that accrues on a balance after the monthly statement is produced, but before the balance is repaid. This additional interest is typically added to the following monthly statement. U.S. Senator Carl Levin raised the issue of millions of Americans affected by hidden fees, compounding interest and cryptic terms. Their woes were heard in a Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations hearing which was chaired by Senator Levin, who said that he intends to keep the spotlight on credit card companies and that legislative action may be necessary to purge the industry.[100] In 2009, the C.A.R.D. Act was signed into law, enacting protections for many of the issues Levin had raised.

Hidden costs edit

In the United Kingdom, merchants won the right through The Credit Cards (Price Discrimination) Order 1990[101] to charge customers different prices according to the payment method; this was later removed by the EU's 2nd Payment Services Directive. As of 2007, the United Kingdom was one of the world's most credit card-intensive countries, with 2.4 credit cards per consumer, according to the U.K. Payments Administration Ltd.[102]

In the United States until 1984, federal law prohibited surcharges on card transactions. Although the federal Truth in Lending Act provisions that prohibited surcharges expired that year, a number of states have since enacted laws that continue to outlaw the practice; California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Kansas, Massachusetts, Maine, New York, Oklahoma, and Texas have laws against surcharges. As of 2006, the United States probably had one of the world's highest if not the top ratio of credit cards per capita, with 984 million bank-issued Visa and MasterCard credit card and debit card accounts alone for an adult population of roughly 220 million people.[103] The credit card per U.S. capita ratio was nearly 4:1 as of 2003[104] and as high as 5:1 as of 2006.[105]

Over-limit charges edit

United Kingdom edit

Consumers who keep their account in good order by always staying within their credit limit, and always making at least the minimum monthly payment will see interest as the biggest expense from their card provider. Those who are not so careful and regularly surpass their credit limit or are late in making payments were exposed to multiple charges, until a ruling from the Office of Fair Trading[106] that they would presume charges over £12 to be unfair which led the majority of card providers to reduce their fees to £12.

The higher fees originally charged were claimed to be designed to recoup the card operator's overall business costs and to try to ensure that the credit card business as a whole generated a profit, rather than simply recovering the cost to the provider of the limit breach, which has been estimated as typically between £3–£4. Profiting from a customer's mistakes is arguably not permitted under U.K. common law if the charges constitute penalties for breach of contract, or under the Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1999.

Subsequent rulings in respect of personal current accounts suggest that the argument that these charges are penalties for breach of contract is weak, and given the Office of Fair Trading's ruling it seems unlikely that any further test case will take place.

Whilst the law remains in the balance, many consumers have made claims against their credit card providers for the charges that they have incurred, plus interest that they would have earned had the money not been deducted from their account. It is likely that claims for amounts charged in excess of £12 will succeed, but claims for charges at the OFT's £12 threshold level are more contentious.

United States edit

The Credit CARD Act of 2009 requires that consumers opt in to over-limit charges. Some card issuers have therefore commenced solicitations requesting customers to opt into over-limit fees, presenting this as a benefit as it may avoid the possibility of a future transaction being declined. Other issuers have simply discontinued the practice of charging over-limit fees. Whether a customer opts into the over-limit fee or not, banks will in practice have discretion as to whether they choose to authorize transactions above the credit limit or not. Of course, any approved over-limit transactions will only result in an over-limit fee for those customers who have opted into the fee. This legislation took effect on 22 February 2010. Following this Act, the companies are now required by law to show on a customer's bills how long it would take them to pay off the balance.

France edit

What is called a credit card in the United States - meaning the customer has a bill to pay at the end of the month - does not exist in the French banking system. A debit card debits the customer's account as the transaction is made, while a credit card debits it at the end of the month automatically, making it impossible to fall into debt by forgetting to pay a credit card bill. Specialized credit companies can provide these cards, but they are separate from the regular banking system. In this case, the consumer decides the maximum amount which can not be exceeded.

Credit scores or credit history do not exist in France, and therefore the need to build a credit history through credit cards does not exist. Personal information cannot be shared among banks, which means there is no centralized system for tracking creditworthiness. The only centralized system in France is for individuals who have not repaid credit or issued checks without sufficient funds or those who file for bankruptcy. This system is handled by the Banque de France.[107]

Vietnam edit

In Vietnam, there are currently over 39 million active credit cards.[108][109] Credit limits in this country are set by the bank or card issuing organization based on various factors such as the applicant's income, credit score, credit history, and personal financial profile.[110][111] Credit limits can be adjusted upon request and agreement between the user and the card provider.[112][113] The penalty for exceeding the credit limit is set by each bank and usually ranges from 1% to 5% of the over-the-limit amount per month.[114][115] In addition, cardholders will also be charged interest on the amount spent over the limit.[116][117]

European Union edit

- Interchange fee cap: The interchange fee is a fee paid between banks for the acceptance of card-based transactions, and it is usually a percentage of the transaction amount. In the EU, the interchange fee is capped:

- For debit cards, a maximum of 0.2% of the transaction amount. This cap also applies to universal cards, which can function as both debit and credit cards.

- For credit cards, a maximum of 0.3% of the transaction amount.

In comparison interchange fees in Canada average 1.78%, and 1.73% in the US.[118]

These caps are designed to prevent excessive fees and ensure a level playing field for all financial institutions.

- Fees Outside the Country of Origin Cap: According to EU regulations, payment and withdrawal fees outside the country of origin are unlawful. This means that a French customer withdrawing money in Italy cannot be made to pay more fees than a withdrawal in France. The same rule applies to payments made with credit or debit cards. In general, this means that there are no additional fees for using a credit card abroad.

Neutral consumer resources edit

Canada edit

The Government of Canada maintains a database of the fees, features, interest rates and reward programs of nearly 200 credit cards available in Canada. This database is updated on a quarterly basis with information supplied by credit card issuing companies. Information in the database is published every quarter on the website of the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada (FCAC).[119]

Information in the database is published in two formats. It is available in PDF comparison tables that break down the information according to the type of credit card, allowing the reader to compare the features of, for example, all the student credit cards in the database. The database also feeds into an interactive tool on the FCAC website.[120] The interactive tool uses several interview-type questions to build a profile of the user's credit card usage habits and needs, eliminating unsuitable choices based on the profile, so that the user is presented with a small number of credit cards and the ability to carry out detailed comparisons of features, reward programs, interest rates, etc.

Credit cards in ATMs edit

Many credit cards can be used in an ATM to withdraw money against the credit limit extended to the card, but many card issuers charge interest on cash advances before they do so on purchases. The interest on cash advances is commonly charged from the date the withdrawal is made, and unlike interest on purchases, the interest on cash advances is not waived even if the customer pays the statement balance in full. Many card issuers levy a commission for cash withdrawals, even if the ATM belongs to the same bank as the card issuer. Merchants do not offer cashback on credit card transactions because they would pay a percentage commission of the additional cash amount to their bank or merchant services provider, thereby making it uneconomical. Discover is a notable exception to the above. A customer with a Discover card may get up to $120 cashback if the merchant allows it. This amount is simply added to the card holder's cost of the transaction and no extra fees are charged as the transaction is not considered a cash advance.

In the US, many credit card companies will also when applying payments to a card, do so, for the matter at hand, at the end of a billing cycle, and apply those payments to everything before cash advances. For this reason, many consumers have large cash balances, which have no grace period and incur interest at a rate that is (usually) higher than the purchase rate, and will carry those balances for years, even if they pay off their statement balance each month. This practice is not permitted in the UK, where the law states that any payments must be assigned to the balance bearing the highest rate of interest first.

Acceptance mark edit

An acceptance mark is a logo or design that indicates which card schemes an ATM or merchant accepts. Common uses include decals and signs at merchant locations or in merchant advertisements. The purpose of the mark is to provide the cardholder with the information where his or her card can be used. An acceptance mark differs from the card product name (such as American Express Centurion card, Eurocard), as it shows the card scheme (group of cards) accepted. An acceptance mark however corresponds to the card scheme mark shown on a card.

An acceptance mark is however not an absolute guarantee that all cards belonging to a given card scheme will be accepted. On occasion cards issued in a foreign country may not be accepted by a merchant or ATM due to contractual or legal restrictions.

Credit cards as funding for entrepreneurs edit

Credit cards and prepaid cards[47] are a very risky way for entrepreneurs to acquire capital for their start ups when more conventional financing is unavailable. Len Bosack and Sandy Lerner used personal credit cards[121] to start Cisco Systems. Larry Page and Sergey Brin's start up of Google was financed by credit cards to buy the necessary computers and office equipment, more specifically "a terabyte of hard disks".[122][failed verification] Similarly, filmmaker Robert Townsend financed part of Hollywood Shuffle using credit cards.[123] Director Kevin Smith funded Clerks in part by maxing out several credit cards.[124] Actor Richard Hatch also financed his production of Battlestar Galactica: The Second Coming partly through his credit cards. Famed hedge fund manager Bruce Kovner began his career (and, later on, his firm Caxton Associates) in financial markets by borrowing from his credit card. U.K. entrepreneur James Caan (as seen on Dragons' Den) financed his first business using several credit cards.

However, these stories are outliers, as more than 80% of all startups fail in their first year,[125] leaving anyone who attempts this method of financing their startup with significant personal costs, as credit cards are in the name of a person, rather than that of a business.

Cashback reward programs edit

Cashback reward programs are incentive programs established by credit card issuers to encourage use of the card. Spending on the card typically awards the card users with points or cash-points that allow the user to redeem to rewards, such as gift cards, statement credits/cash deposited in an account of the card user's choice, or exchanging them to Frequent Flyer programs. Spending that qualifies for these type of points can include/exclude balance transfers, payday loans, or cash advances. Points typically have no cash value until redeemed via the issuer.

Depending on the type of card, rewards will generally cost the issuer between 0.25% and 2.0% of the spread. Networks such as Visa or MasterCard have increased their fees to allow issuers to fund their rewards system. Some issuers discourage redemption by forcing the cardholder to call customer service for rewards. On their servicing website, redeeming awards is usually a feature that is very well hidden by the issuers.[126] Many credit card issuers, particularly those in the United Kingdom, Canada and United States, run these programs to encourage use of the card.

Card holders typically receive between 0.5% and 3% of their net expenditure (purchases minus refunds) as an annual rebate, which is either credited to the credit card account or paid to the card holder separately.[127] Unlike unused gift cards, in whose case the breakage in certain U.S. states goes to the state's treasury,[128] unredeemed credit card points are retained by the issuer.[129]

A 2010 public policy study conducted by the Federal Reserve concluded cash back reward programs result in a monetary transfer from low-income to high-income households. Eliminating cash back reward programs would reduce merchant fees which would in turn reduce consumer prices because retail is such a competitive environment.[130]

Costs of rewards program to the merchant edit

When accepting payment by credit card, merchants typically pay a percentage of the transaction amount in commission to their bank or merchant services provider. Merchants are often not allowed to charge a higher price when a credit card is used as opposed to other methods of payment, so there is no penalty for a card holder to use their credit card. The credit card issuer is sharing some of this commission with the card holder to incentivise them to use the credit card when making a payment. Rewards-based credit card products like cash back are more beneficial to consumers who pay their credit card statement off every month. Rewards-based products generally have higher annual percentage rates. If the balance is not paid in full every month, the extra interest will eclipse any rewards earned. Most consumers do not know that their rewards-based credit cards charge higher "interchange" fees to the vendors who accept them.[131]

See also edit

- Card (disambiguation)

- Accountable fundraising

- ATM card

- Billing descriptor

- Cashback website

- Compulsive shopping

- Credit card hijacking

- Credit rating agency

- Credit reference agency

- Criticism of credit scoring systems in the United States

- Debit card

- Debt-lag

- Dynamic currency conversion, or DCC

- Electronic money

- Fair Credit Reporting Act

- Identity theft

- Installment credit

- International Card Manufacturers Association

- Payment card

- Purchasing card

References edit

- ^ a b O'Sullivan, Arthur; Sheffrin, Steven M. (2003). Economics: Principles in action (Textbook). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 261. ISBN 0-13-063085-3.

- ^ The World Bank. "Credit card ownership (% age 15+)". World Bank Gender Data Portal. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ^ Schneider, Gary (2010). Electronic Commerce. Cambridge: Course Technology. p. 497. ISBN 978-0-538-46924-1.

- ^ "Payment Cards in Circulation Worldwide" (PDF). Nilson Report. October 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 November 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ^ "Charts & Graphs Archive". Nilson Report. Archived from the original on 12 May 2023. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ^ "Payment Cards in the U.S. Projected". Nilson Report. Archived from the original on 24 October 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ^ Gabrielle, Natasha (19 April 2022). "Credit and Debit Card Market Share by Network and Issuer". fool.com. Retrieved 24 October 2022.