Charleston is a city in, and the county seat of, Coles County, Illinois, United States.[3] The population was 17,286, as of the 2020 census. The city is home to Eastern Illinois University and has close ties with its neighbor, Mattoon. Both are principal cities of the Charleston–Mattoon Micropolitan Statistical Area.

Charleston, Illinois | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname: Chucktown | |

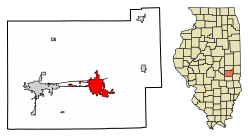

Location of Charleston in Coles County, Illinois. | |

| Coordinates: 39°29′03″N 88°10′41″W / 39.48417°N 88.17806°W[1] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Coles |

| Townships | Charleston, Hutton, Lafayette, Seven Hickory |

| Founded | 1831 |

| Incorporation | 1865 |

| Founded by | Benjamin Parker |

| Named for | Charles Morton - Postmaster |

| Government | |

| • Type | City Manager |

| • City Manager | R. Scott Smith |

| • Mayor | Brandon Combs |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9.59 sq mi (24.83 km2) |

| • Land | 8.88 sq mi (23.01 km2) |

| • Water | 0.70 sq mi (1.82 km2) |

| Elevation | 699 ft (213 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 17,286 |

| • Density | 1,945.75/sq mi (751.23/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Code(s) | 61920 |

| Area code(s) | 217, 447 |

| FIPS code | 17-12567 |

| GNIS ID | 2393803[1] |

| Wikimedia Commons | Charleston, Illinois |

| Website | www |

History

editNative Americans lived in the Charleston area for thousands of years before the first European settlers arrived. With the great tallgrass prairie to the west, beech-maple forests to the east, and the Embarras River and Wabash Rivers between, the Charleston area provided semi-nomadic Indians access to a variety of resources. Indians may have deliberately set the "wildfires" which maintained the local mosaic of prairie and oak–hickory forest. Streams with names such as 'Indian Creek' and 'Kickapoo Creek' mark the sites of former Indian settlements. One village is said to have been located south of Fox Ridge State Park near a deposit of flint.[citation needed]

The early history of settlement in the area was marked by uneasy co-existence between Indians and European settlers. Some settlers lived peacefully with the natives, but conflict arose in the 1810s and 1820s. After Indians allegedly harassed surveying crews, an escalating series of poorly documented skirmishes occurred between Indians, settlers, and the Illinois Rangers. Two pitched battles (complete with cannon on one side) took place just south of Charleston along "the hills of the Embarrass," near the entrance to Lake Charleston park. These conflicts did not slow American settlement, and Indian history in Coles County effectively ended when all natives were expelled by law from Illinois after the 1832 Black Hawk War. With the grudging exception of Indian wives, the last natives were driven out by the 1840s.[4]

First settled by Benjamin Parker in 1826, Charleston was named for Charles Morton, its first postmaster.[5] The city was established in 1831, but not incorporated until 1865. When Abraham Lincoln's father moved to a farm on Goosenest Prairie south of Charleston in 1831, Lincoln helped him move, then left to start his own homestead at New Salem in Sangamon County. Lincoln was a frequent visitor to the Charleston area, though he likely spent more time at the Coles County courthouse than at the home of his father and stepmother. One of the famous Lincoln–Douglas debates was held in Charleston on September 18, 1858, and is now the site of the Coles County fairgrounds and a small museum.[6][7] Lincoln's last visit was in 1859, when the future President visited his stepmother and his father's grave.

Although Illinois was a solidly pro-Union, anti-slavery state, Coles County was settled by many Southerners with pro-slavery sentiments. In 1847, the county was divided when prominent local citizens offered refuge to a family of escaped slaves brought from Kentucky by Gen. Robert Matson. Abe Lincoln, by then a young railroad lawyer, appeared in the Coles County Courthouse to argue for the return of the escaped slaves under the Fugitive Slave Act in a case known as Matson v. Ashmore. As in the rest of the nation, this long-simmering debate finally broke out into violence during the American Civil War. On March 28, 1864 a riot—or perhaps a small battle—erupted in downtown Charleston when armed Confederate sympathizers known as Copperheads arrived in town to attack half-drunk Union soldiers preparing to return to their regiment.[8]

In 1895, the Eastern Illinois State Normal School was established in Charleston, which later became Eastern Illinois University. This led to lasting resentment in nearby Mattoon, which had originally led the campaign to locate the proposed teaching school in Coles County. A Mattoon newspaper printed a special edition announcing the decision with the derisive headline "Catfish Town Gets It."

Thomas Lincoln's log cabin has been restored and is open to the public as the Lincoln Log Cabin State Historic Site, 8 mi. south of Charleston. The Lincoln farm is maintained as a living history museum where historical re-enactors depict life in 1840s Illinois. Thomas and Sarah Bush Lincoln are buried in the nearby Shiloh Cemetery.[citation needed]

On May 26, 1917, a tornado ripped through Charleston, killing 38 people and injuring many more, along with destroying 220 homes.[9][4]

Geography

editAccording to the 2021 census gazetteer files, Charleston has a total area of 9.59 square miles (24.84 km2), of which 8.88 square miles (23.00 km2) (or 92.68%) is land and 0.70 square miles (1.81 km2) (or 7.32%) is water.[10]

Climate

editThe data below were taken from 1893 through January 2020, when this chart was made. They were accessed through the Western Regional Climate Center (WRCC).[11]

| Climate data for Charleston, Illinois (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1896–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 71 (22) |

75 (24) |

89 (32) |

92 (33) |

101 (38) |

108 (42) |

110 (43) |

107 (42) |

104 (40) |

94 (34) |

84 (29) |

73 (23) |

110 (43) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 37.9 (3.3) |

43.3 (6.3) |

54.3 (12.4) |

67.3 (19.6) |

77.1 (25.1) |

85.5 (29.7) |

88.1 (31.2) |

86.6 (30.3) |

81.2 (27.3) |

68.9 (20.5) |

54.4 (12.4) |

42.4 (5.8) |

65.6 (18.7) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 29.3 (−1.5) |

33.9 (1.1) |

44.0 (6.7) |

55.7 (13.2) |

65.6 (18.7) |

74.2 (23.4) |

77.2 (25.1) |

75.5 (24.2) |

69.0 (20.6) |

57.3 (14.1) |

44.6 (7.0) |

34.3 (1.3) |

55.0 (12.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 20.7 (−6.3) |

24.6 (−4.1) |

33.6 (0.9) |

44.1 (6.7) |

54.1 (12.3) |

63.0 (17.2) |

66.2 (19.0) |

64.4 (18.0) |

56.8 (13.8) |

45.6 (7.6) |

34.9 (1.6) |

26.1 (−3.3) |

44.5 (6.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −27 (−33) |

−23 (−31) |

−14 (−26) |

14 (−10) |

26 (−3) |

35 (2) |

45 (7) |

39 (4) |

25 (−4) |

11 (−12) |

−2 (−19) |

−20 (−29) |

−27 (−33) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.54 (65) |

2.69 (68) |

3.11 (79) |

5.09 (129) |

4.52 (115) |

4.84 (123) |

4.40 (112) |

2.94 (75) |

3.15 (80) |

3.94 (100) |

3.74 (95) |

2.79 (71) |

43.75 (1,111) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 8.1 (21) |

5.5 (14) |

1.3 (3.3) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.8 (2.0) |

3.0 (7.6) |

19.0 (48) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.2 | 8.3 | 10.7 | 12.0 | 12.9 | 10.4 | 9.2 | 8.1 | 7.8 | 9.5 | 10.4 | 10.6 | 120.2 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 4.1 | 2.6 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 3.2 | 11.9 |

| Source: NOAA[12][13] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 849 | — | |

| 1870 | 2,849 | — | |

| 1880 | 2,867 | 0.6% | |

| 1890 | 4,135 | 44.2% | |

| 1900 | 5,488 | 32.7% | |

| 1910 | 5,884 | 7.2% | |

| 1920 | 6,615 | 12.4% | |

| 1930 | 8,012 | 21.1% | |

| 1940 | 8,197 | 2.3% | |

| 1950 | 9,164 | 11.8% | |

| 1960 | 10,505 | 14.6% | |

| 1970 | 16,421 | 56.3% | |

| 1980 | 19,355 | 17.9% | |

| 1990 | 20,398 | 5.4% | |

| 2000 | 21,039 | 3.1% | |

| 2010 | 21,838 | 3.8% | |

| 2020 | 17,286 | −20.8% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[14] | |||

As of the 2020 census[15] there were 17,286 people, 7,847 households, and 3,850 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,803.25 inhabitants per square mile (696.24/km2). There were 8,319 housing units at an average density of 867.83 per square mile (335.07/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 79.65% White, 8.39% African American, 0.27% Native American, 2.54% Asian, 0.13% Pacific Islander, 3.88% from other races, and 5.13% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 5.84% of the population.

There were 7,847 households, out of which 20.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 33.06% were married couples living together, 12.18% had a female householder with no husband present, and 50.94% were non-families. 36.05% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.57% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.68 and the average family size was 2.13.

The city's age distribution consisted of 12.7% under the age of 18, 32.5% from 18 to 24, 24.6% from 25 to 44, 18.4% from 45 to 64, and 11.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 27.7 years. For every 100 females, there were 91.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.9 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $41,436, and the median income for a family was $52,521. Males had a median income of $24,609 versus $16,650 for females. The per capita income for the city was $23,901. About 16.8% of families and 27.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 24.5% of those under age 18 and 5.7% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

editCharleston is home to Eastern Illinois University, which has roughly 8,600 undergraduate and graduate students.[16] Additionally, Eastern Illinois hosts the Illinois High School Association's Girls Badminton, Journalism, and Girls and Boys Track and Field State Finals.[17]

The establishment of an enterprise zone on the northern edge of Charleston has helped attract some manufacturing and industrial jobs, including Vesuvius USA,[18] ITW Hi-Cone, and Dietzgen Corporation.[19]

Jimmy John Liautaud founded the first Jimmy John's restaurant in Charleston in 1983,[20] occupying premises near the corner of Fourth Street and Lincoln Avenue.[21]

Arts and Culture

editCharleston is home to the annual Coles County Fair, which typically runs for a week in the summer. The fair includes animal showings, carnival rides and attractions, a demolition derby, and more. The fair is held at the fairgrounds located at 603 W Madison Ave.

Museums and Libraries

edit- Charleston Carnegie Public Library

- EIU Tarble Arts Center

- Doudna Fine Arts Center

- Lincoln Douglas Debate Museum

- Five Mile House

Parks and Recreation

editCharleston has seven parks (one of which is a state park) and six trails, only one of which is not part of Lake Charleston (the Lincoln Prairie Grass Trail).

Lake Charleston

editLake Charleston lies approximately two miles (3 km) southeast of the city center. It covers 330 acres of surface area, and has a maximum depth of 12 feet (3.7 m) and average depth of 5.7 feet (1.7 m).[22] Fishing and boating are allowed, although there is a no-wake regulation. There are five trails in the park area around the lake, with the longest trail looping around the lake with a length of 3.6 miles (5.8 km).[23]

List of Parks

edit- Fox Ridge State Park

- Morton Park

- Sister City Park

- Kiwanis Park

- North Park

- VFW Way Park

- Reasor Park

Parks and Recreation Department

editCharleston's Parks and Recreation Department offers a variety of services, including before & after school clubs, a day club, dog training classes, and children sports leagues.[24]

Government

editCity Manager

editCharleston is run under a City Manager style of government, where the City Manager is the city's chief administrative officer and oversees the City Council. The City Manager is an appointed position. As of September 18, 2003, R. Scott Smith, a former Parks & Recreation director, officially became Charleston's City Manager after serving as interim manager since August 9, 2003[25] and continues to hold that position as of January 2022.[26]

City Council and Mayor

editThe City Council is an elected legislative body of the City of Charleston, of which the mayor is a part. They make policy decisions based on recommendations and information from the City Manager.[27] Brandon Combs was appointed mayor of Charleston June 30, 2015 and continues to hold the office.[28]

Education

editCharleston is served by Charleston Community Unit School District 1, one of three school districts located in the county of Coles. The district itself is composed of six schools: Ashmore Elementary School (PreK-4), Mark Twain Elementary School (PreK and K), Carl Sandburg Elementary School (1-3), Jefferson Elementary School (4-6), Charleston Middle School (7-8), and Charleston High School (9-12).[29]

Eastern Illinois University is a public university in Charleston and has served the community since 1895; and Lakeview College of Nursing has a campus located in Charleston.

Media

editCharleston is served by the JG-TC (Journal Gazette & Times Courier) local newspaper and Eastern Illinois University's daily newspaper The Daily Eastern News

Infrastructure

editCharleston is located approximately 7 miles (11 km) east of Interstate 57's Mattoon exit. Illinois Route 16 serves as the city's main east-west road, titled Lincoln Ave. within city limits.

Highways

edit- Illinois Route 16 (Lincoln Ave.)

- Illinois Route 130 (18th St./Olive Ave.)

- Illinois Route 316 (Madison Ave./State St.)

Airport

editCharleston is served by the Coles County Memorial Airport (MTO), which is approximately 6 miles (9.7 km) west of Charleston. Established in 1953, the airport received commercial service until 2000, and now serves as a public general aviation facility.

Mass Transit

editCharleston is serviced by two transit providers: the Charleston Zipline run by Dial-A-Ride which serves the general city area with a deviated fixed-route and demand-response service,[30] and the Panther Shuttle, which mainly services the Eastern Illinois University campus.[31]

Rail

editCharleston does not receive direct passenger rail service, however Amtrak's Illini and Saluki and City of New Orleans routes stop in neighboring Mattoon. Freight-wise, Charleston was serviced by the Eastern Illinois Railroad, which was acquired by the Decatur & Eastern Illinois Railroad, which now services businesses in the region.

Healthcare

editCharleston is serviced by the Sarah Bush Lincoln Health Center, whose main campus is approximately 6 miles (9.7 km) west of Charleston. There is a Walk-In Clinic located within the city itself.

Notable people

edit- Kim Chizevsky-Nicholls, IFBB pro bodybuilder

- Ronald W. Davis, director of the Stanford Genome Technology Center, biochemist, geneticist

- Frank K. Dunn, Chief Justice of the Illinois Supreme Court

- Jim Edgar, governor of Illinois from 1990 to 1998, was raised in Charleston and graduated from Eastern Illinois University

- Jeff Gossett, longtime journeyman punter who played in the NFL for 16 years

- George Hilton Jones III, historian and author

- Joshua Scott Jones, Big Machine Records recording artists (country music) and one-half of the duo "Steel Magnolia"

- Tom Koch, longtime comedy writer for Mad Magazine and Bob and Ray

- David Lamb, musician and songwriter for Brown Bird; born in Charleston in 1977

- James John Liautaud, founder of the Jimmy John's restaurant franchise

- Lee Lynch, Illinois newspaper editor and politician

- Rex Morgan, basketball player

- Marty Pattin, pitcher for the California Angels, Seattle Pilots/Milwaukee Brewers, Boston Red Sox and Kansas City Royals

- Curtis Price, the Principal of the Royal Academy of Music and a professor of music at the University of London; was raised in Charleston[citation needed]

- Zeke Rosebraugh, pitcher for the Pittsburgh Pirates; born in Charleston

- Stan Royer, former Major League Baseball player. Graduated from Charleston High School

- Willis R. Shaw, Illinois state senator; born in Charleston[32]

- Larry Stuffle, member of the Illinois House of Representatives from 1977 to 1985. He was born in Charleston and represented the area in the Illinois House of Representatives.[33]

- Gregg Toland, cinematographer of Citizen Kane and Wuthering Heights (for which he won an Oscar), was born and raised in Charleston.

References

edit- ^ a b c U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Charleston, Illinois

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ a b "The Mattoon/Charleston Tornado of May 26, 1917". National Weather Service. NOAA. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

- ^ Charleston – Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ^ "Charleston, Coles County, September 18, 1858". The Lincoln-Douglas Debates. The Lincoln Institute. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- ^ "Fourth Debate: Charleston, Illinois". Lincoln Home National Historic Site. National Park Service. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- ^ Illinois Copperheads: Analyzing the Documents Archived January 7, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ May–June 1917 tornado outbreak sequence

- ^ "Gazetteer Files". Census.gov. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- ^ "CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS - Climate Summary". wrcc.dri.edu. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Charleston, IL". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ "Eastern Illinois University reports 10.5% enrollment gain".

- ^ "EIU - IHSA State Championships". www.eiu.edu. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ "Where We Operate". Vesuvius. Archived from the original on September 22, 2016. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- ^ "Locations". Dietzgen Corporation. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- ^ Construction begins on new Jimmy John's, by Dave Fopay, JG-TC Online, September 27, 2005

- ^ Jimmy John's Gourmet Sandwiches

- ^ "CHARLESTON SIDE CHANNEL LAKE (LAKE CHARLESTON)" (PDF). 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 24, 2021.

- ^ "Trail Map" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 17, 2020.

- ^ "Parks and Recreation Department". Archived from the original on October 16, 2020.

- ^ "Smith officially becomes City Manager". December 4, 2003. Archived from the original on January 13, 2022. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- ^ "Administration". Archived from the original on October 16, 2020.

- ^ "City Council". Archived from the original on May 9, 2013.

- ^ "City Election Results". Archived from the original on May 9, 2013.

- ^ "Charleston CUSD#1 School District" (PDF). www.charleston.k12.il.us. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ "Coles County ZIPLINE". Archived from the original on March 17, 2020.

- ^ "Panther Shuttle". Archived from the original on August 6, 2011.

- ^ 'Illinois Blue Book 1915–1916,' Biographical Sketch of Willis R. Shaw, pg. 122

- ^ "Larry Ray Stuffle 1949-2016". The State Journal-Register. January 18, 2016. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

Further reading

edit- Kleen, Michael. "The Copperhead Threat in Illinois: Peace Democrats, Loyalty Leagues, and the Charleston Riot of 1864." Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 105.1 (2012): 69-92. online

- Parkinson, John Scott. "Bloody spring: The Charleston, Illinois riot and Copperhead violence during the American Civil War" (PhD dissertation, Miami University; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1998. 9912834).