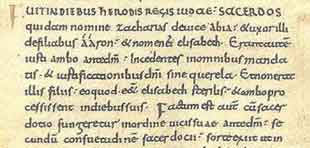

Carolingian minuscule or Caroline minuscule is a script which developed as a calligraphic standard in the medieval European period so that the Latin alphabet of Jerome's Vulgate Bible could be easily recognized by the literate class from one region to another. It is thought to have originated before 778 CE at the scriptorium of the Benedictine monks of Corbie Abbey, about 150 kilometres (95 miles) north of Paris, and then developed by Alcuin of York for wide use in the Carolingian Renaissance.[1][2][3] Alcuin himself still wrote in a script which was a precursor to the Carolingian minuscule, which slowly developed over three centuries.[4][5] He was most likely responsible for copying and preserving the manuscripts[6] and upkeep of the script.[7] It was used in the Holy Roman Empire between approximately 800 and 1200. Codices, pagan and Christian texts, and educational material were written in Carolingian minuscule.

After blackletter developed out of it, the Carolingian minuscule became obsolete, until the 14th century Italian Renaissance, when the humanist minuscule script was also developed from it. By this latter line the Carolingian minuscule is a direct ancestor of most modern-day Latin letter scripts and typefaces.

Creation edit

The script is derived from Roman half uncial and the insular scripts that were being used in Irish and English monasteries. The strong influence of Irish literati on the script can be seen in the distinctively cló-Gaelach (Irish style) forms of the letters, especially a, e, d, g, s, and t.

Carolingian minuscule was created partly under the patronage of the Emperor Charlemagne (hence Carolingian). Charlemagne had a keen interest in learning, according to his biographer Einhard (here with apices):

Temptábat et scríbere, tabulásque et códicellós ad hoc in lectó sub cervícálibus circumferre solébat, ut, cum vacuum tempus esset, manum litterís effigiendís adsuésceret, sed parum successit labor praeposterus ac séró incohátus.

He also tried to write, and used to keep tablets and blanks in bed under his pillow, that at leisure hours he might accustom his hand to form the letters; however, as he did not begin his efforts in due season, but late in life, they met with ill success.

This new script was significantly more legible than the scripts used by Romans or that of the script earlier in the Middle Ages, and offered new features such as word spacing, more punctuation, an introduction of lower-case letters, and conventions such as usage of upper-case for titles, a mix of upper and lower case for subtitles, and lower case for the body of a text.[3] Although Charlemagne was never fully literate, he understood the value of literacy and a uniform script in running his empire. Charlemagne sent for the English scholar Alcuin of York to run his palace school and scriptorium at his capital, Aachen. Efforts to supplant Gallo-Roman and Germanic scripts had been under way before Alcuin arrived at Aachen, where he was master from 782 to 796, with a two-year break. The new minuscule was disseminated first from Aachen, of which the Ada Gospels provided classic models, and later from the influential scriptorium at Marmoutier Abbey (Tours), where Alcuin withdrew from court service as an abbot in 796 and restructured the scriptorium.[8]

Characteristics edit

Carolingian minuscule was uniform with rounded shapes in clearly distinguishable glyphs, disciplined and above all, legible. Clear capital letters and spaces between words became standard in Carolingian minuscule, which was one result of a campaign to achieve a culturally unifying standardization across the Carolingian Empire.[9]

Traditional charters, however, continued to be written in a Merovingian "chancery hand" long after manuscripts of Scripture and classical literature were being produced in the minuscule hand. Documents written in a local language, like Gothic or Anglo-Saxon rather than Latin, tended to be expressed in traditional local script.

Carolingian script generally has fewer ligatures than other contemporary scripts, although the et (&), æ, rt, st, and ct ligatures are common. The letter d often appears in an uncial form with an ascender slanting to the left, but the letter g is essentially the same as the modern minuscule letter, rather than the previously common uncial ᵹ. Ascenders are usually "clubbed" – they become thicker near the top.[9]

The early period of the script, during Charlemagne's reign in the late 8th century and early 9th, still has widely varying letter forms in different regions. The uncial form of the letter a, similar to a double c (cc), is still used in manuscripts from this period. There is also use of punctuation such as the question mark, as in Beneventan script of the same period. The script flourished during the 9th century, when regional hands developed into an international standard, with less variation of letter forms. Modern glyphs, such as s and v, began to appear (as opposed to the "long s" ſ and u), and ascenders, after thickening at the top, were finished with a three-cornered wedge. The script began to evolve slowly after the 9th century. In the 10th and 11th centuries, ligatures were rare and ascenders began to slant to the right and were finished with a fork. The letter w also began to appear. By the 12th century, Carolingian letters had become more angular and were written closer together, less legibly than in previous centuries; at the same time, the modern dotted i appeared. [citation needed]

Spread edit

The new script spread through Western Europe most widely where Carolingian influence was strongest. In luxuriously produced lectionaries that now began to be produced for princely patronage of abbots and bishops, legibility was essential. It reached far afield: the 10th century Freising manuscripts, which contain the oldest Slovene language, the first Roman-script record of any Slavic language, are written in Carolingian minuscule. In Switzerland, Carolingian was used in the Rhaetian and Alemannic minuscule types. Manuscripts written in Rhaetian minuscule tend to have slender letters, resembling Insular script, with the letters ⟨a⟩ and ⟨t⟩, and ligatures such as ⟨ri⟩, showing similar to Visigothic and Beneventan. Alemannic minuscule, used for a short time in the early 9th century, is usually larger, broader, and very vertical in comparison to the slanting Rhaetian type. It was developed by the monk Wolfcoz I at the Abbey of Saint Gall.[10] In the Holy Roman Empire, Carolingian script flourished in Salzburg, Austria, as well as in Fulda, Mainz, and Würzburg, all of which were major centers of the script. German minuscule tends to be oval-shaped, very slender, and slanted to the right. It has uncial features as well, such as the ascender of the letter ⟨d⟩ slanting to the left, and vertical initial strokes of ⟨m⟩ and ⟨n⟩.

In northern Italy, the monastery at Bobbio used Carolingian minuscule beginning in the 9th century. Outside the sphere of influence of Charlemagne and his successors, however, the new legible hand was resisted by the Roman Curia; nevertheless the Romanesca type was developed in Rome after the 10th century. The script was not taken up in England and Ireland until ecclesiastic reforms in the middle of the 10th century; in Spain a traditionalist Visigothic hand survived; and in southern Italy a 'Beneventan minuscule' survived in the lands of the Lombard duchy of Benevento through the 13th century, although Romanesca eventually also appeared in southern Italy.

Role in cultural transmission edit

Scholars during the Carolingian Renaissance sought out and copied in the new legible standardized hand many Roman texts that had been wholly forgotten. Most of contemporary knowledge of classical literature derives from copies made in the scriptoria of Charlemagne. Over 7000 manuscripts written in Carolingian script survive from the 8th and 9th centuries alone.

Though the Carolingian minuscule was superseded by Gothic blackletter hands, in retrospect, it seemed so thoroughly 'classic' to the humanists of the early Renaissance that they took these old Carolingian manuscripts to be ancient Roman originals, and used them as bases for their Renaissance hand, the "humanist minuscule".[11] From there the script passed to the 15th- and 16th-century printers of books, such as Aldus Manutius of Venice. In this way it forms the basis of our modern lowercase typefaces. Indeed, 'Carolingian minuscule' is a style of typeface, which approximates this historical hand, eliminating the nuances of size of capitals, long descenders, and so on.

See also edit

References edit

- ^ Knox, E.L. Skip. "Carolingian Handwriting", Boise State University

- ^ "Caroline Minuscule Predates Charlemagne", Heidelberg University, 9 January 2013

- ^ a b Colish, Marcia L. (1999). Medieval Foundations of the Western Intellectual Tradition, 400–1400. The Yale Intellectual History of the West. Yale University Press. p. 67. ISBN 9780300078527.

- ^ Rosamond, McKitterick. The Frankish Kingdoms Under the Carolingians, 751-987. Routledge, 2018, 150-157.

- ^ Dales, Douglas (2013). Alcuin II: Theology and Thought. ISD LLC. ISBN 978-0-227-90087-1.

- ^ Bowen, James (2018). Hist West Educ:Civil Europe V2. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-50096-1.

- ^ Morison, Stanley (2009). Selected Essays On the History of Letter-forms in Manuscript and Print. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-18316-1.

- ^ The production of the scriptorium at Tours was reconstructed by Rand, Edward Kennard (1929). A Survey of the Manuscripts of Tours. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780910956024 – via Medieval Academy of America.

- ^ a b Slimane, Fouad; Schaban, Torsten; Margner, Volker (August 2014). "GMM-based handwriting style identification system for historical documents". 2014 6th International Conference of Soft Computing and Pattern Recognition (SoCPaR). Tunis, Tunisia: IEEE. p. 389. doi:10.1109/SOCPAR.2014.7008038. ISBN 978-1-4799-5934-1. S2CID 14350674.

- ^ "Wolfcoz I" (in German). Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ^ Ullman, Berthold Louis (1960). The Origin and Development of Humanistic Script. Rome: Ed. di Storia e Letteratura. p. 12. GGKEY:SC91X3J9KAG.

External links edit

- 'Manual of Latin Palaeography' (A comprehensive PDF file containing 82 pages profusely illustrated, January 2024).

- Carolingian minuscule at Dr. Dianne Tillotson's website devoted to medieval writing

- Pfeffer Mediæval, a Carolingian minuscule typeface which also includes Gothic and Runic characters

- Network for the Study of Caroline Minuscule, an international forum dedicated to the study of the script

- More information at Earlier Latin Manuscripts