Canning is a method of food preservation in which food is processed and sealed in an airtight container (jars like Mason jars, and steel and tin cans). Canning provides a shelf life that typically ranges from one to five years,[a] although under specific circumstances, it can be much longer.[2] A freeze-dried canned product, such as canned dried lentils, could last as long as 30 years in an edible state.

In 1974, samples of canned food from the wreck of the Bertrand, a steamboat that sank in the Missouri River in 1865, were tested by the National Food Processors Association. Although appearance, smell, and vitamin content had deteriorated, there was no trace of microbial growth and the 109-year-old food was determined to be still safe to eat.[3]

History and development

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2021) |

French origins

editShortly before the Napoleonic Wars, the French government offered a hefty cash award of 12,000 francs to any inventor who could devise a cheap and effective method of preserving large amounts of food to create well-preserved military rations for the Grande Armée. The larger armies of the period required increased and regular supplies of quality food. Limited food availability was among the factors limiting military campaigns to the summer and autumn months. In 1809, Nicolas Appert, a French confectioner and brewer, observed that food cooked inside a jar did not spoil unless the seals leaked, and developed a method of sealing food in glass jars.[4] Appert was awarded the prize in 1810 by Count Montelivert, a French minister of the interior.[5] The reason for lack of spoilage was unknown at the time, since it would be another 50 years before Louis Pasteur demonstrated the role of microbes in food spoilage and developed pasteurization.

The Grande Armée began experimenting with issuing canned foods to its soldiers, but the slow process of canning and the even slower development and transport stages prevented the army from shipping large amounts across the French Empire, and the wars ended before the process was perfected.

Following the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the canning process was gradually employed in other European countries and the United States.

In the United Kingdom

editBased on Appert's methods of food preservation, the tin can process was allegedly developed by Frenchman Philippe de Girard, who came to London and used British merchant Peter Durand as an agent to patent his own idea in 1810.[6] Durand did not pursue food canning himself, selling his patent in 1811 to Bryan Donkin and John Hall, who were in business as Donkin Hall and Gamble, of Bermondsey.[7] Bryan Donkin developed the process of packaging food in sealed airtight cans, made of tinned wrought iron. Initially, the canning process was slow and labour-intensive, as each large can had to be hand-made, and took up to six hours to cook, making canned food too expensive for ordinary people.

The main market for the food at this stage was the British Army and Royal Navy. By 1817, Donkin recorded that he had sold £3000 worth of canned meat in six months. In 1824, Sir William Edward Parry took canned beef and pea soup with him on his voyage to the Arctic in HMS Fury, during his search for a northwestern passage to India. In 1829, Admiral Sir James Ross also took canned food to the Arctic, as did Sir John Franklin in 1845.[8] Some of his stores were found by the search expedition led by Captain (later Admiral Sir) Leopold McClintock in 1857. One of these cans was opened in 1939 and was edible and nutritious, though it was not analysed for contamination by the lead solder used in its manufacture.

In Europe

editDuring the mid-19th century, canned food became a status symbol among middle-class households in Europe, being something of a frivolous novelty. Early methods of manufacture employed poisonous lead solder for sealing the cans. Studies in the 1980s attributed the lead from the cans as a factor in the disastrous outcome of the 1845 Franklin expedition to chart and navigate the Northwest Passage.[9] However, studies in 2013 and 2016 suggested that lead poisoning was likely not a factor, and that the crew's ill health may, in fact, have been due to malnutrition—specifically zinc deficiency—possibly due to a lack of meat in their diet.[10][11]

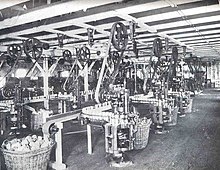

Increasing mechanization of the canning process, coupled with a huge increase in urban populations across Europe, resulted in a rising demand for canned food. A number of inventions and improvements followed, and by the 1860s smaller machine-made steel cans were possible, and the time to cook food in sealed cans had been reduced from around six hours to thirty minutes.

In the United States

editCanned food also began to spread beyond Europe—Robert Ayars established the first American canning factory in New York City in 1812, using improved tin-plated wrought-iron cans for preserving oysters, meats, fruits, and vegetables. Demand for canned food greatly increased during wars. Large-scale wars in the nineteenth century, such as the Crimean War, American Civil War, and Franco-Prussian War, introduced increasing numbers of working-class men to canned food, and allowed canning companies to expand their businesses to meet military demands for non-perishable food, enabling companies to manufacture in bulk and sell to wider civilian markets after wars ended. Urban populations in Victorian Britain demanded ever-increasing quantities of cheap, varied, quality food that they could keep at home without having to go shopping daily. In response, companies such as Underwood, Nestlé, Heinz, and others provided quality canned food for sale to working class city-dwellers. The late 19th century saw the range of canned food available to urban populations greatly increase, as canners competed with each other using novel foodstuffs, highly decorated printed labels, and lower prices.

World War I

editDemand for canned food skyrocketed during World War I, as military commanders sought vast quantities of cheap, high-calorie food to feed their millions of soldiers, which could be transported safely, survive trench conditions, and not spoil in transport. Throughout the war, British soldiers generally subsisted on low-quality canned food, such as the British bully beef, pork and beans, canned sausages, and Maconochie's stew, but by 1916, widespread dissatisfaction and increasing complaints about the poor quality canned food among soldiers resulted in militaries seeking better-quality food to improve morale, and complete meals-in-a-can began to appear. In 1917, the French Army began issuing canned French cuisine such as coq au vin, beef bourguignon, french onion soup, and Vichyssoise, while the Italian Army experimented with canned ravioli, spaghetti bolognese, minestrone, and pasta e fagioli. After the war, companies that had supplied military canned food began to improve the quality of their goods for civilian sale.

Methods

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2021) |

The original fragile and heavy glass containers presented challenges for transportation, and glass jars were largely replaced in commercial canneries with cylindrical tin can or wrought-iron canisters (later shortened to "cans") following the work of Peter Durand (1810). Cans are cheaper and quicker to make, and much less fragile than glass jars.

Can openers were not invented for another thirty years. At first, soldiers would cut the cans open with bayonets or smash them open with rocks.[citation needed] Today, tin-coated steel is the material most commonly used. Aseptically processed retort pouches are also used for canning.

Glass jars have remained popular for some high-value products and in home canning.

Microbial control

editTo prevent the food from being spoiled before and during containment, a number of methods are used: pasteurisation, boiling (and other applications of high temperature over a period of time), refrigeration, freezing, drying, vacuum treatment, antimicrobial agents that are natural to the recipe of the foods being preserved, a sufficient dose of ionizing radiation, submersion in a strong saline solution, acid, base, osmotically extreme (for example very sugary) or other microbially-challenging environments.

Other than sterilization, no method is perfectly dependable as a preservative. Sterilization is done after the can is sealed, so that both the container and the food are secured.

The spores of the microorganism Clostridium botulinum (which causes botulism) can be eliminated only at temperatures above the boiling point of water. As a result, from a public safety point of view, foods with low acidity (a pH more than 4.6) need sterilization under high temperature (116–130 °C). To achieve temperatures above the boiling point requires the use of a pressure canner. Foods that must be pressure canned include most vegetables, meat, seafood, poultry, and dairy products. The only foods that may be safely canned in an ordinary boiling water bath are highly acidic ones with a pH below 4.6, such as fruits, pickled vegetables, or other foods to which acidic additives have been added. Although an ordinary boiling temperature does not kill botulism spores, the acidity is enough to stop them from growing.[12]

Sealing: double seams

editInvented in 1888 by Max Ams,[13] modern double seams provide an airtight seal to a can. This airtight nature is crucial to keeping micro-organisms out of the can and keeping the can's contents sealed inside. Thus, double seamed cans are also known as Sanitary Cans. Developed in 1900 in Europe, this sort of can was made of the traditional cylindrical body made with tin plate. The two ends (lids) were attached using what is now called a double seam. A can thus sealed is impervious to contamination by creating two tight continuous folds between the can's cylindrical body and the lids. This eliminated the need for solder and allowed improvements in manufacturing speed, reducing cost.

Double seaming uses rollers to shape the can, lid and the final double seam. To make a sanitary can and lid suitable for double seaming, manufacture begins with a sheet of coated tin plate. To create the can body, rectangles are cut and curled around a die, and welded together creating a cylinder with a side seam.

Rollers are then used to flare out one or both ends of the cylinder to create a quarter circle flange around the circumference. Precision is required to ensure that the welded sides are perfectly aligned, as any misalignment will cause inconsistent flange shape, compromising its integrity.

A circle is then cut from the sheet using a die cutter. The circle is shaped in a stamping press to create a downward countersink to fit snugly into the can body. The result can be compared to an upside down and very flat top hat. The outer edge is then curled down and around about 140 degrees using rollers to create the end curl.

The result is a steel tube with a flanged edge, and a countersunk steel disc with a curled edge. A rubber compound is put inside the curl.

Seaming

editThe body and end are brought together in a seamer and held in place by the base plate and chuck, respectively. The base plate provides a sure footing for the can body during the seaming operation and the chuck fits snugly into the end (lid). The result is the countersink of the end sits inside the top of the can body just below the flange. The end curl protrudes slightly beyond the flange.

First operation

editOnce brought together in the seamer, the seaming head presses a first operation roller against the end curl. The end curl is pressed against the flange curling it in toward the body and under the flange. The flange is also bent downward, and the end and body are now loosely joined. The first operation roller is then retracted. At this point five thicknesses of steel exist in the seam. From the outside in they are:

- End

- Body Hook

- Cover Hook

- Body

- Countersink

Second operation

editThe seaming head then engages the second operation roller against the partly formed seam. The second operation presses all five steel components together tightly to form the final seal. The five layers in the final seam are then called; a) End, b) Body Hook, c) Cover Hook, d) Body, e) Countersink. All sanitary cans require a filling medium within the seam because otherwise the metal-to-metal contact will not maintain a hermetic seal. In most cases, a rubberized compound is placed inside the end curl radius, forming the critical seal between the end and the body.

Probably the most important innovation since the introduction of double seams is the welded side seam. Prior to the welded side seam, the can body was folded and/or soldered together, leaving a relatively thick side seam. The thick side seam required that the side seam end juncture at the end curl to have more metal to curl around before closing in behind the Body Hook or flange, with a greater opportunity for error.

Seamer setup and quality assurance

editMany different parts during the seaming process are critical in ensuring that a can is airtight and vacuum sealed. The dangers of a can that is not hermetically sealed are contamination by foreign objects (bacteria or fungicide sprays), or that the can could leak or spoil.

One important part is the seamer setup. This process is usually performed by an experienced technician. among the parts that need setup are seamer rolls and chucks which have to be set in their exact position (using a feeler gauge or a clearance gauge). The lifter pressure and position, roll and chuck designs, tooling wear, and bearing wear all contribute to a good double seam.

Incorrect setups can be non-intuitive. For example, due to the springback effect, a seam can appear loose, when in reality it was closed too tight and has opened up like a spring. For this reason, experienced operators and good seamer setup are critical to ensure that double seams are properly closed.

Quality control usually involves taking full cans from the line – one per seamer head, at least once or twice per shift, and performing a teardown operation (wrinkle/tightness), mechanical tests (external thickness, seamer length/height and countersink) as well as cutting the seam open with a twin blade saw and measuring with a double seam inspection system. The combination of these measurements will determine the seam's quality.

Use of a statistical process control (SPC) software in conjunction with a manual double-seam monitor, computerized double seam scanner, or even a fully automatic double seam inspection system makes the laborious process of double seam inspection faster and much more accurate. Statistically tracking the performance of each head or seaming station of the can seamer allows for better prediction of can seamer issues, and may be used to plan maintenance when convenient, rather than to simply react after bad or unsafe cans have been produced.[14]

Nutritional value

editCanning is a way of processing food to extend its shelf life. The idea is to make food available and edible long after the processing time. A 1997 study found that canned fruits and vegetables are as rich with dietary fiber and vitamins as the same corresponding fresh or frozen foods, and in some cases the canned products are richer than their fresh or frozen counterparts.[15] The heating process during canning appears to make dietary fiber more soluble, and therefore more readily fermented in the colon into gases and physiologically active byproducts. Canned tomatoes have a higher available lycopene content. Consequently, canned meat and vegetables are often among the list of food items that are stocked during emergencies.[16]

Potential hazards

editIn the beginning of the 19th century the process of canning foods was mainly done by small canneries. These canneries were full of overlooked sanitation problems, such as poor hygiene and unsanitary work environments. Since the refrigerator did not exist and industrial canning standards were not set in place it was very common for contaminated cans to slip onto the grocery store shelves.[17]

According to The Fruits of Empire: Art, Food and the Politics of Race in the Age of American Expansion by Shana Klein, "Workers also suffered injuries, specifically bruised knuckles and open sores, from trimming and packaging pineapples. Gloves were one preventative measure to protect a canner's hands from the acidity of the pineapple, but gloves did not always help."[18]

Migration of can components

editIn canning toxicology, migration is the movement of substances from the can itself into the contents.[19] Potential toxic substances that can migrate are lead, causing lead poisoning, or bisphenol A (BPA), a potential endocrine disruptor that is an ingredient in the epoxy commonly used to coat the inner surface of cans. Some cans are manufactured with a BPA-free enamel lining produced from plant oils and resins.[20] In February 2018, the Can Manufacturers Institute, a trade association in the United States, surveyed the industry and reported that at least 90% of food cans no longer contained BPA.[21]

Salt content

editSalt (sodium chloride), dissolved in water, is used in the canning process.[22][dubious – discuss] As a result, canned food can be a major source of dietary salt.[23] Too much salt increases the risk of health problems, including high blood pressure. Therefore, health authorities have recommended limitations of dietary sodium.[24][25][26][27][28] Many canned products are available in low-salt and no-salt alternatives.

Rinsing thoroughly after opening may reduce the amount of salt in canned vegetables, since much of the salt content is thought to be in the liquid, rather than the food itself.[29]

Botulism

editFoodborne botulism results from contaminated foodstuffs in which C. botulinum spores have been allowed to germinate and produce botulism toxin,[30] and this typically occurs in canned non-acidic food substances that have not received a strong enough thermal heat treatment. C. botulinum prefers low oxygen environments and is a poor competitor to other bacteria, but its spores are resistant to thermal treatments. When a canned food is sterilized insufficiently, most other bacteria besides the C. botulinum spores are killed, and the spores can germinate and produce botulism toxin.[30] Botulism is a rare but serious paralytic illness, leading to paralysis that typically starts with the muscles of the face and then spreads towards the limbs.[31] The botulinum toxin is extremely dangerous because it cannot be detected by sight or smell, and ingestion of even a small amount of the toxin can be deadly.[32] In severe forms, it leads to paralysis of the breathing muscles and causes respiratory failure. In view of this life-threatening complication, all suspected cases of botulism are treated as medical emergencies, and public health officials are usually involved to prevent further cases from the same source.[31]

Canning and economic recession

editCanned goods and canning supplies sell particularly well in times of recession due to the tendency of financially stressed individuals to engage in cocooning, a term used by retail analysts to describe the phenomenon in which people choose to stay at home instead of adding expenditures to their budget by dining out and socializing outside the home.[citation needed]. Also, some people may become preppers and proceed to stockpile canned food.[33] A doomer would also be interested in stockpiling canned food upon learning about a recession.

In February 2009 during a recession, the United States saw an 11.5% rise in sales of canning-related items.[34]

Some communities in the US have county canning centers which are available for teaching canning, or shared community kitchens which can be rented for canning one's own foods.[35]

Occupation

editSee also

edit- Amanda Jones, inventor of a vacuum method of canning.

- Steel and tin cans, most commonly associated with canned food

- Home canning

- Canned fish

- Food industry

- Food preservation

- Canned water

- List of canneries

- Canstruction non-profit organisation

Notes

edit- ^ According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), "canned foods are safe indefinitely as long as they are not exposed to freezing temperatures, or temperatures above 90 °F (32.2 °C)". If the cans look okay, they are safe to use. Discard cans that are dented, rusted, or swollen. High-acid canned foods (tomatoes, fruits) will keep their best quality for 12 to 18 months; low-acid canned foods (meats, vegetables) for 2 to 5 years.[1]

References

edit- ^ "Food_Product_Dating". Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ "Arctic Explorers Uncover (and Eat) 60-Year-Old Food Stash". Smithsonian. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ Blumenthal, Dale (September 1990). "The Canning Process; Old Preservation Technique Goes Modern". FDA Consumer. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019.

- ^ (in French) appert-aina.com Archived 7 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Applied Nutrition and Food Technology, Jesse D. Dagoon, 1989; p. 2.

- ^ Geoghegan, Tom (21 April 2013). "The story of how the tin can nearly wasn't". BBC News. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ^ A brief account of Bryan Donkin FRS and the company he founded 150 years ago. Bryan Donkin Company, Chesterfield, 1953

- ^ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ^ "Canned Food Sealed Icemen's Fate". History Today.

- ^ Witze, Alexandra (2016). "Fingernail absolves lead poisoning in death of Arctic explorer". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.21128. S2CID 131781828.

- ^ "Researchers acquit the tins in mysterious failed Franklin expedition". Phys.org.

- ^ William Schafer (9 January 2009). "Home Canning Tomatoes". Extension.umn.edu. Archived from the original on 1 July 2010. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ^ Mark Q. Sutton, Archaeological laboratory methods: an introduction Archived 4 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Kendall/Hunt Pub., 1996, p. 172

- ^ Quality Assurance for the Food Industry: A Practical Approach by J. Andres Vasconcellos

- ^ Rickman (2007). "Nutritional comparison of fresh, frozen, and canned fruits and vegetables". Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 87 (7): 1185–1196. doi:10.1002/jsfa.2824.

- ^ "Food Supplies To Stock For Emergencies". earthquake-survival-kits.org. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ Petrick, G. (2008). Feeding the masses: H.J. Heinz and the creation of industrial food. Endeavour, 33(1), 29–34.

- ^ Klein, Shana (2020). The fruits of empire : art, food, and the politics of race in the age of American expansion. Oakland, California. ISBN 978-0-520-29639-8. OCLC 1133661556.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Clive Maier; Theresa Calafut (2008). Polypropylene: The Definitive User's Guide and Databook. Elsevier Science. ISBN 978-0-08-095041-9. Archived from the original on 4 December 2017.

- ^ "Can-Don't: Cooking Canned Foods in Their Own Containers Comes with Risks". Scientific American. 2017. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 17 October 2017. Accessed 2017-10-17

- ^ McTigue Pierce, Lisa (20 February 2018). "Most food cans no longer use BPA in their linings". Packaging Digest.

- ^ Definition of brine Archived 4 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine, BusinessDictionary

- ^ "Sodium (Salt or Sodium Chloride)". American Heart Association. 24 May 2010. Archived from the original on 8 February 2010.

- ^ "American Heart Association 2010 Dietary Guidelines" (PDF). 2010 Dietary Guidelines. American Heart Association. 23 January 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- ^ "Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand – Sodium". Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand. Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council/ New Zealand Ministry of Health. Archived from the original on 29 September 2009. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- ^ "Dietary Guidelines focus on sodium intake, sugary drinks, dairy alternatives". Food Navigator-usa.com. Decision News Media. 27 April 2010. Archived from the original on 6 May 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- ^ "Sodium Chloride". Eat Well, Be Well. UK Government Food Standards Agency. Archived from the original on 7 October 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- ^ "Health Canada, Healthy Living, Sodium". Healthy Living. Health Canada. 2008. Archived from the original on 4 March 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- ^ "How to Remove Sodium From Canned Vegetables". Livestrong.com. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ a b Botox and Botulism? Beauty and the Beast? Archived 28 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine From Ingrid Koo, PhD, for About.com. Updated: 16 December 2008

- ^ a b Sobel J (October 2005). "Botulism". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 41 (8): 1167–73. doi:10.1086/444507. PMID 16163636.

- ^ "Home-Canned Foods | Botulism". CDC. 14 July 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ Bowles, Nellie (24 April 2020). "I Used to Make Fun of Silicon Valley Preppers. Then I Became One - In tech circles, gearing up for the apocalypse was a cliché. Now it's a credential". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ Gregory, Sean (11 March 2009). "What Sells in a Recession: Canned Goods and Condoms". Time. Archived from the original on 16 April 2010. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ Canneries, Canning Centers, Community Kitchens, Commercial Kitchens for Rent, Local Canning Resources and Food Business Incubators – Commercial Canning for Your Home Produce Archived 18 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Pickyourown.org

Further reading

edit- FDA 21 CFR 113.3 Thermally processed low acid foods packaged in hermetically sealed containers Revision Apr. 2006

- Potter, N. N. and Hotchkiss, J. H. Food Science (5th ed). Springer, 1999

- Fellows, P. J. Food Processing Technology: Principles and Practice (2nd Edition). Woodhead Pub. 1999

- Zeide, Anna (6 March 2018). Canned: The Rise and Fall of Consumer Confidence in the American Food Industry. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520290686.

External links

edit- National Center for Home Food Preservation

- Boston Public Library, USA. Canned food advertisements, various dates